Art has from the very beginning been deeply intertwined with reflections on our position within the cosmos and what this might teach us of mortality. My goal with “Cosmos Cinema” was to consider how these themes are addressed by artists working both historically and today, and to place these artists into new sets of relations.

Installation view of Space Is the Place at the 14th Shanghai Biennale: “Cosmos Cinema,” 2023–24. Photo courtesy of Power Station of Art.

It is tempting to associate stargazing with imaginative escapism. With sheer scale and implacable beauty, the cosmos shows manifest disinterest in human affairs. Here is something, we take comfort in thinking, that we cannot possibly fuck up. But this division between our world and the one beyond is dangerous: colonizers said similar things about the “new world.” Like all such divisions, it’s also patently absurd.

Andreeva’s cosmos is a place not to be conquered technologically but to be imagined on its own terms. In the tradition of Russian cosmism, with its utopian and technically unspecific dreams of resurrecting all the dead fathers buried on earth and resettling them on distant twinkling planets, we might say, borrowing from Robert Bird, that she is cosmic-minded, rather than space-race minded.

Critics of SETI have consistently argued that the program is more closely aligned with an unauthorized diplomatic project than it is with the hard sciences. While valid, a more imminent danger is that the transmissions might reveal the location of earth to extraterrestrials harboring violent intentions. Some scientists and philosophers have, therefore, raised the question of whether we should divulge anything—or at least anything truthful—within these transmissions.

Deception plays such a foundational role in the cosmic power struggles of the Three Body saga that its central tenet, the Dark Forest Theory, gained traction in wider cultural discourses. This theory likens intelligent life in the universe to hunters dispersed in a dark forest, vying for limited resources and unaware of each other’s locations. Silence and deceitfulness are essential to survival, given that the exposure of one’s coordinates will likely invite direct attack.

How should Eisenstein’s double-page collage from an unrealized 1927 film adaptation of Marx’s Capital be seen today, almost a hundred years later? I would suggest reading these pages as proto-cinematic cartography, a divination which addresses future cinema as a chaosmos: a montage of the visceral, the sensuous, and the sidereal, cosmic dimensions which exclude homogeneous linear temporality.

Wanderings’ status as a foundational classic of the PRC demands a closer look at its “genre” and its spectatorial address in the context of China’s—and the Shanghai film industry’s—momentous midcentury transformation. The 1949 film’s mixture of live action and animation reasserts the primacy of “movement and light” as the foundation of cinematic realism. With this view, we might also rescue realism from the presumption of indexicality and examine the intricate relationship between formally experimental filmmaking—including animation—and historical change.

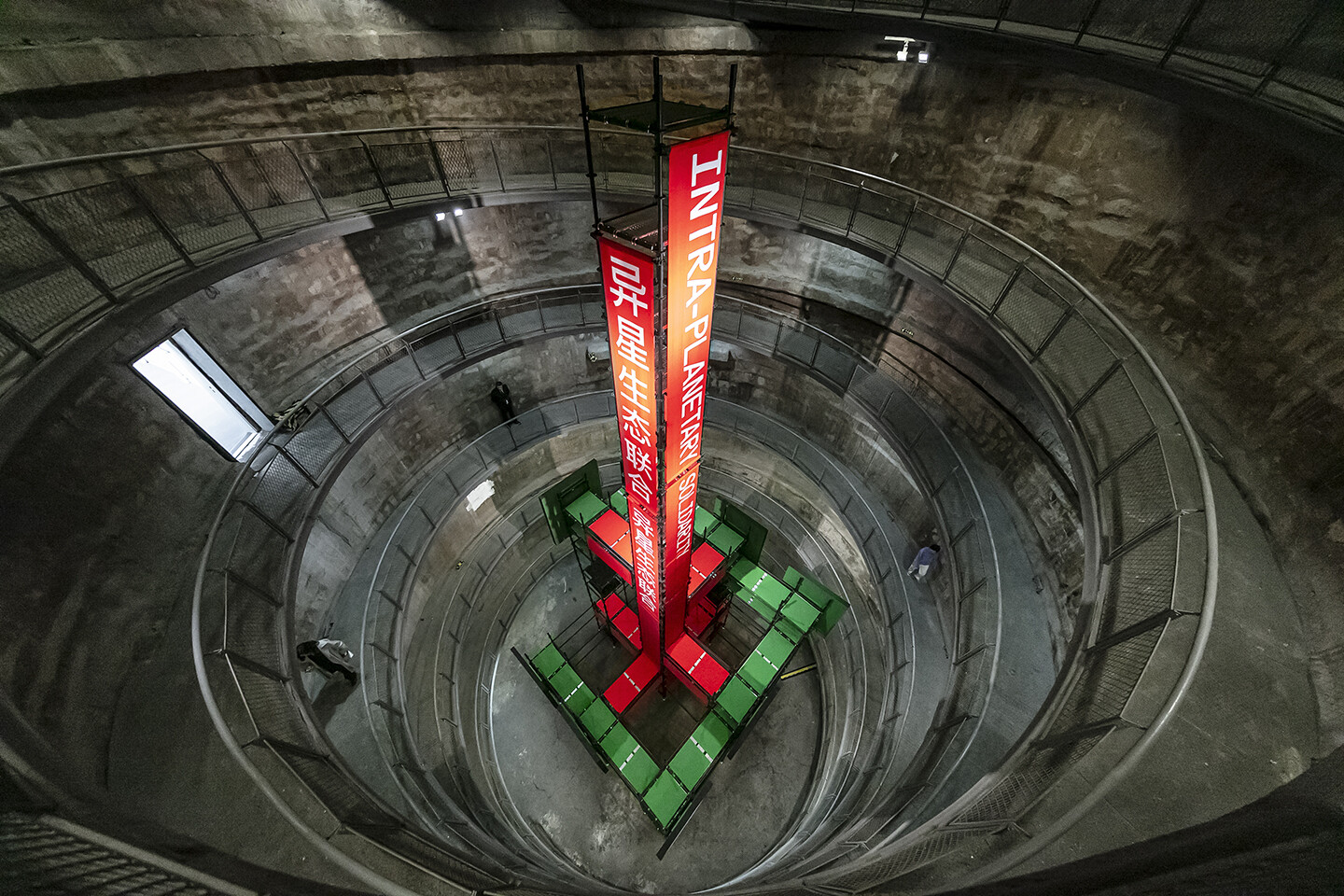

In the coming decade, humans will likely become an interplanetary species by creating permanent settlements on the moon and Mars. This endeavor clearly reproduces a terrible colonial and imperialist legacy that shamelessly speaks of martian “colonies” and a new generation of space “pioneers.” To challenge these environmentally disastrous space missions and the neocolonial, imperialist models they plan to export into the cosmos, we terrestrial beings need to alter the very foundations of our exo-ecologies in the making.

The concept of total cinema gives rise to the endeavor to recreate the world in cinema’s image. Yet even as many previously unattainable technological dreams become reality, none of them are sufficient to substitute for existing reality. In André Bazin’s view, cinema has an asymptotic relationship to reality. The medium might approach perfect realism but can never attain what he calls “the myth of total cinema”—in which the boundaries between the world and its representation dissolve into an authoritarian totality—precisely because reality itself is constantly changing.

An AI image generator was given the prompt “salmon swimming in a river.” It produced several puzzling images of similar composition, each of which shows what is unquestionably salmon in a stream of water. However, none of the results matched the familiar image of a legendary piscine hero swimming full-bodied against the current. Instead, they all depicted a fraction of a salmon, a fillet of salmon, its pink flesh ready to be seared or made into sashimi. In AI’s defense, the algorithm did not interpret the prompt incorrectly. All the right elements are there: this is not a pig in a volcano. Yet it all appears wrong to human eyes.

Methodologically speaking, it might be said that all of Ilya and Emilia Kabakov’s installations are in some way or another connected with a special structured experience of space, echoing the transformations of the starry sky. But there is one installation in which the sky also becomes the center of gravity. We are talking about perhaps their most famous installation, The Man Who Flew into Space from His Apartment, first shown in the Kabakovs’ Moscow studio in 1985. The viewer is presented with a room in a communal apartment that has been sealed off by investigators. The room’s resident has, with the help of a homemade device, escaped Soviet reality and is hiding in the sky.