So long as [the theoreticians of the proletarian class] look for science and merely make systems, so long as they are at the beginning of the struggle, they see in poverty nothing but poverty, without seeing in it the revolutionary, subversive side, which will overthrow the old society.

—Karl Marx (1847)Civility is solidarity for elites.

—Internet wisdom, anonymous (2022)

I. Thus Spoke Herr Keuner

In 1930 Bertolt Brecht introduced the fictional character “Herr Keuner,” who became a major figure of Walter Benjamin’s interest in his friend’s work.1 Benjamin assumed that Herr Keuner’s name was “based on the Greek root κοινός [koinós]—the universal, that which concerns all, belongs to all.”2 However, Herr Keuner is not the universal man, the humanist Allmensch, but rather Mr. Nobody—Herr Keiner. If pronounced in Brecht’s Swabian dialect, the equivocity of Keiner and Keuner cannot be missed. Brecht’s Herr Keuner lingers on both extremes of the modern city dweller. He is anonymous and synonymous; he’s nobody and everyone.3 Herr Keuner, as Benjamin adds, “is the man who concerns all, belongs to all, for he is the leader. But in quite a different sense from the one we usually understand by the word. He is in no way a public speaker, a demagogue; nor is he a show-off or a strongman.”4

Herr Keuner, “the thinking one,” is a guide without doctrine, a leader without leadership. He behaves too flexibly to give shape to any clear ordering principles—he is “infinitely cunning, infinitely discreet, infinitely polite, infinitely old, and infinitely adaptable.”5 Rather than a character with attributes, Herr Keuner is an impoverished figuration of material poverty. Brecht included the following tale in his first series of Keuner Stories:

Mr. Keuner came by his ideas on the distribution of poverty while reflecting on mankind. One day, looking around his apartment, he decided he wanted different furniture—cheaper, shabbier, not so well made. He immediately went to a joiner and asked him to scrape the varnish from his furniture. But when the varnish had been scraped off, the furniture did not look shabby, but merely ruined. Nevertheless, the joiner’s bill had to be paid, and Mr. Keuner also had to throw away his pieces of furniture and buy new ones—shabby, cheap, not so well made—because he wanted them so badly. Some people who heard about this laughed at Mr. Keuner, since his shabby furniture had turned out more expensive than the varnished kind. But Mr. Keuner said: “Poverty does not mean saving, but spending. I know you: your poverty does not suit your ideas. But wealth does not suit my ideas.”6

This vignette, titled “The bad is not cheap, either,” contains a glimmer of Benjamin’s take on poverty and on Brecht himself. Material wealth did not suit Benjamin’s thought, either. The latter’s critique of bourgeois thought brings Herr Keuner’s insight to the domain of intellectual production. If society’s poverty does not suit its ideas, materialist thought must first be adjusted to poor reality then change it. The same year Brecht’s Keuner Stories first appear, Benjamin apodictically notes: “Thought should become impoverished, it should only be permitted insofar as it is socially realizable.”7 In a later essay, entitled “Erfahrung und Armut” (Experience and poverty), Benjamin gives a further twist to the same provocation: “With this tremendous development of technology, a completely new poverty has descended on mankind. And the reverse side of this poverty is the oppressive wealth of ideas that has been spread among people.”8

The “oppressive” nature of the “wealth of ideas” only comes into view once we accept Benjamin’s diagnosis of a specifically modern Erfahrungsarmut, or “poverty of experience.”9 The last years of the Weimar Republic were marked by a severe economic downturn following the stock market crash of October 29, 1929. In the early 1930s, “poverty” meant economic poverty above any other connotation. Benjamin broadens the concept to encompass its cultural and aesthetic scope: in the age of the capitalist mode of technological reproducibility, poverty not only affects our perception and modes of experience—it also reduces the human being to its basic needs. Economic-existential impoverishment through capitalist relations of production imposes a negative simplification, a “radi-zation” or root (radix) extraction to which theory must respond.10 Before getting into details of his intricate argument, let us consider his response to experiential poverty. In 1933, shortly after the Nazi’s rise to power in Germany, Benjamin calls for a “new, positive concept of barbarism.” Turning negative depravation into a positive feature of antifascist reduction, the new barbarian is not embodied by the Nazi regime but by one that is ready “to start from scratch; to make a new start; to make a little go a long way; to begin with a little and build up further, looking neither left nor right.”11 Within the realm of theory, this new start must begin with theory itself. Benjamin’s imperative is to turn the poverty of experience into the impoverishment of theory.

In terms of Brecht’s story about Herr Keuner’s furniture, we have rejected the fantasy of (re)gaining the opulent splendor of “good old” handicraft furniture as well as the temptations of expensive vintage aesthetics. But will acknowledging our poverty of experience prevent us from consuming the opium of nostalgia, from yearning for vintage replacements? For the new barbarian, cultural artefacts of the past do not only look shabby once modernity aims to artificially revive them; rather, they appear irreversibly ruined. However, there is no “cheap” alternative since austerity or non-consumption is even more expensive in the long run. Brecht’s point is that capitalist economization will not get us better products for less money. Moreover, there is no ethical benefit to paying more for cheaply made new furniture or paying extra for earlier, failed attempts to adjust one’s lifeworld to poverty. With disarming sincerity, Herr Keuner simply insists that a wealth of ideas cannot account for his expensive mode of living with poorly made things. Of course, under the condition of capitalism, Herr Keuner’s poverty is not a choice but a strategy for survival imposed by material conditions themselves.

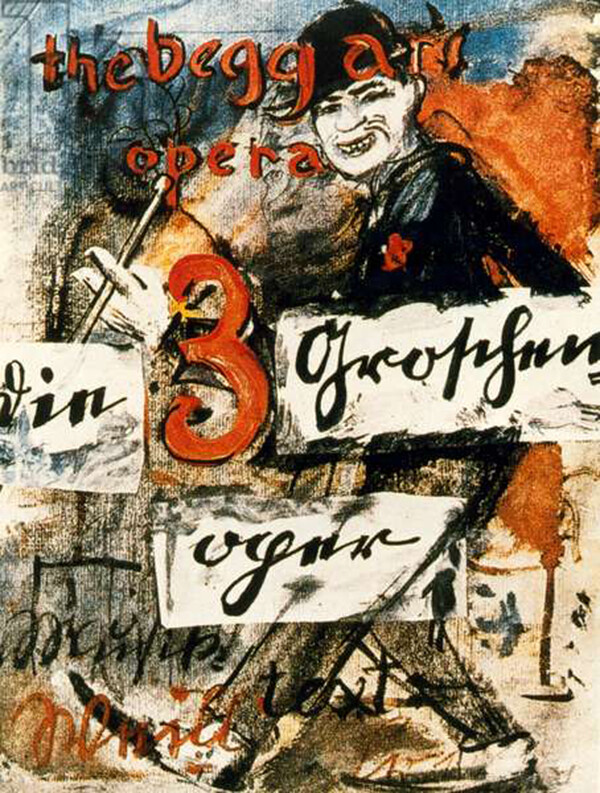

Poster by Caspar Neher for Bertolt Brecht’s The Threepenny Opera, 1928. License: Public domain.

Benjamin, relying on Brecht, draws his own conclusion: while acknowledging the condition of material poverty, he does not call for intellectual modesty, ethical consumption, or economic austerity. On the contrary, Benjamin insists on radicalizing the process of impoverishment by transposing its efficacy onto the realm of ideas and culture. “We have given up one portion of the human heritage after another,” he writes, “and have often left it at the pawnbroker’s for a hundredth of its true value, in exchange for the small change of ‘the contemporary’ [Aktuellen].” Benjamin’s new barbarian will not save his stock by spending the last treasuries of cultural heritage. His communist wager that one day humanity “will repay him with compound interest” has no guarantees.12

The liberal fantasies of Eurocentric civilization, based on progress and humanism, were already discredited before fascism’s rise to power in Germany. Benjamin, hence, never based his political strategy on the cultural “wealth” of Western capitalist acceleration. Already in 1929, during the last year of Weimar Germany’s prosperity, Benjamin joined a surrealist call for an “organization of pessimism”:

Mistrust in the fate of literature, mistrust in the fate of freedom, mistrust in the fate of European humanity, but three times mistrust in all reconciliation: between classes, between nations, between individuals. And unlimited trust only in IG Farben and the peaceful perfecting of the air force.13

Benjamin’s strategy of radicalizing impoverishment is one possible (Brechtian) conclusion drawn from his mistrust in all forms of humanist-idealist reconciliation. Advocating for an impoverishment of thought in the age of capitalist impoverishment is neither progressive nor regressive, neither accelerationist nor decelerationist; rather, it aims to pull a lightning-fast “emergency brake” on the racing train of capitalism.14 This brake is not meant to bring the train’s passengers to their final destination. Pulling it instead enacts an interruption—a redemptive derailing to avoid a catastrophic crash. A Benjaminian figure who can perform this paradoxical task is the new barbarian—the one who inhabits and survives the impoverished space of capitalism without supplementing the “desert of the real” with the wealth of bourgeois humanism.15

II. Modern Barbarism

In antiquity, the barbarian was a foreigner, someone whose language and customs differed from those of the speaker. Barbarians were noncitizens, that is non-Greeks or, later, non-Romans.16 In modernity, the noun “barbarism” acquired its more pejorative sense: an antonym to culture and civilization and their inherent moral values. Anthropological accounts of the nineteenth century framed barbarism as an intermediate state of teleological development from savagery to civilization.17 As John Wesley Powell put it: “In savagery, the powers of nature are feared as evil demons; in barbarism, the powers of nature are worshiped as gods; in civilization, the powers of nature are apprenticed servants.”18

Against this common-sense understanding, Max Horkheimer and Theodor W. Adorno suggested a different concept of barbarism in the mid-1940s. Drawing on Homer’s Iliad, their materialist critique of ideology associated the barbaric way of ancient life with a “state in which no systematic agriculture, and therefore no systematic, time-managing organization of work and society, has yet been achieved.”19 Absent the Christian concept of history and the modern economy of time implemented by the capitalist division of labor, barbaric temporality is structured by myth, governed by mythical laws of fate. However, the overcoming of myth in antiquity already bears traces of the Age of Enlightenment’s dialectical reversal into mythic times and barbarism.

The liberal-bourgeois and later totalitarian failures of the project of civilization reveal the inherent convertibility of myth and enlightenment on the one hand, and barbarism and culture on the other. This revelation of mutability contradicts the humanist belief in the infinite progress of human history. In light of fascism and the Holocaust, the dialectics of enlightenment finally collapse, short-circuiting myth and enlightenment and “culminating objectively in madness”—“a madness of political reality.”20 If enlightenment is not only “mythical fear radicalized” but “totalitarian” itself, “myth is already enlightenment, and enlightenment reverts to mythology.”21 In short, for Horkheimer and Adorno a non-dialectical opposition of barbarism and civilization, myth and enlightenment, cannot be claimed. As we shall see, Benjamin, who in many ways is critical theory’s predecessor and critic, arrived at a similar insight a couple of years before. His dialectical concept of the modern barbarian, however, suggests a different reading of the reversal of culture and barbarism and the implosion of the concept of humanist progress.

Rosa Luxemburg wrote her famous Junius Pamphlet at the dawn of totalitarianism. She drafted the text from prison in early 1915; it was published in 1916 at the height of World War I. Allegedly quoting Friedrich Engels, Luxemburg presents a famous alternative: “Bourgeois society stands at the crossroads, either transition to socialism or regression into barbarism.” And “the triumph of imperialism,” she concludes, “leads to the annihilation of civilization.”22 In its socialist afterlife, Luxemburg’s alternative between socialism and barbarism was translated into the teleological perspective of either progression or regression. But what if Luxemburg’s either/or option had already been decided by capitalist world history—yet in a different way? While conceding that imperialism was about to win the world war at hand, Luxemburg still based her communist wager on the prospective final victory of the class-conscious proletariat.

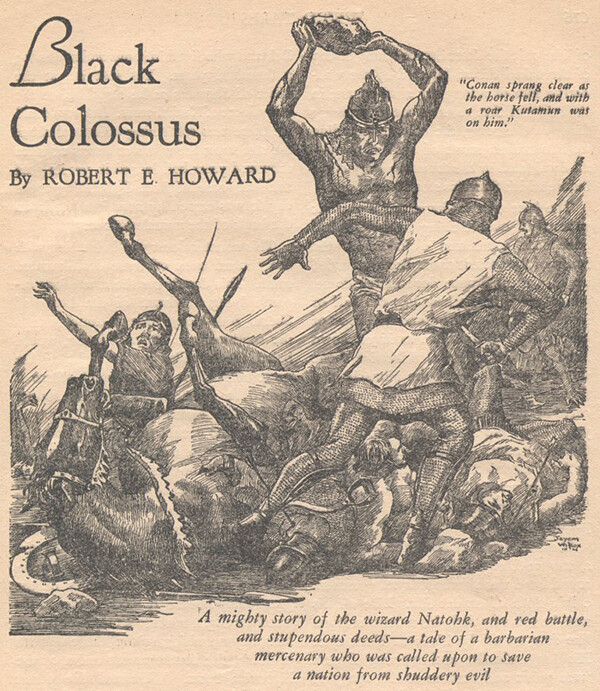

The first artist to create an image of Conan was Jayem Wilcox, 1933.

By 1933, when Walter Benjamin published “Experience and Poverty,” Luxemburg’s Marxist wager was impossible. Imperialism had won the Great War and fascism was ready to prepare the next one. Benjamin’s perspective of defeat, however, is not defeatist. His question is simple: Once the world-historical question of socialism-or-barbarism has been decided in favor of the latter, what is the impoverished horizon of possibility? What kind of communist strategy holds water in a world ablaze with capitalist and fascist barbarism? Could a positive reconfiguration of the barbarian inform a mode of mimetic survival? Is this new barbarian capable of dialectically surpassing capitalism’s barbarism? If bourgeois culture and Western civilization have not only become but are inherently barbaric, barbarism cannot be attacked from the position of bourgeois culture or the vulgar-Marxist belief in progress.23 As Benjamin will later write in the seventh thesis in “On the Concept of History” from 1940:

There is no document of culture which is not at the same time a document of barbarism. And just as such a document is never free of barbarism, so barbarism taints the manner in which it was transmitted from one hand to another. The historical materialist therefore dissociates himself from this process of transmission [Überlieferung] as far as possible. He regards it as his task to brush history against the grain.24

Barbarism and culture are not external oppositions. If there is no document of culture free of barbarism, we may also state the reverse: there is no document of barbarism that is not at the same time a document of culture. For Benjamin, therefore, the dialectical tension of Luxemburg’s wager has not been annulled; rather, its terrain has been shifted, displaced to the realm of barbarism itself. Now, in post-bourgeois capitalism and with the rise of a new fascism, the figure of the barbarian reveals its dialectical nature, allowing for paradoxical positions such as barbaric salvage, regressive progression, and anti-utopian utopia.

Such a dialectical concept of barbarism can be derived from Benjamin’s two German terms for barbarism: Barbarei and Barbarentum.25 While “negative” Barbarei presents the repressed flipside of the artefacts of “positive” culture and civilization, the “positive” Barbarentum or “barbarianhood”26 of the new barbarian designates a mode of adjusting to the “negative” effects of really existing modern Barbarei or barbarism. This adjustment is both destructive and constructive: by releasing the dialectical tension that the negativity of Barbarei entertains vis-à-vis culture and civilization, the new barbarian cuts through the semblance of cultural positivity and its “civilizing” mission.

III. Experience and Poverty

In “Experience and Poverty,” Benjamin contends that with the “tremendous development of technology, a completely new poverty has descended on mankind.” This poverty “is not merely poverty on the personal level, but poverty of human experience in general.”27 Human experiences “in general” are not measured individually and quantitatively but collectively and qualitatively. They are communicable experiences that can be told—shared in storytelling. In his later essay on The Storyteller (1936), Benjamin cited a central passage from his earlier essay to underpin his central argument according to which our ability to exchange experiences has declined in modernity. If “experience [Erfahrung] which is passed on from mouth to mouth is the source from which all storytellers have drawn,” modernity cannot tell stories in the way the old storytellers did.28 Nevertheless, Benjamin’s question is: Can we think of a new technological medium, a coming tradition in which we can embed individual experiences and share them collectively with a linguistic community beyond functional socialization? If tradition is the ability to transmit and pass on collective experiences (Erfahrungen) in a meaningful way, modernity is not simply without tradition. However, the mode of the production of meaning has changed in modernity. If in capitalist modernity “all that is solid melts into air, all that is holy is profaned,” as Marx and Engels famously claimed, the modern experience is also a liquid one.29

The age of capitalist modernity, however, shies away from confronting the material reality of its technological inventions and experiential spaces. The puffy phantasmagorias of cultural property along with the conceptualization of history as the teleological development from prehistory to Western capitalism obstruct attempts to think beyond the capitalist use-value of technology and tradition. Consequently, Benjamin’s critique of cultural history, a bourgeois invention of the age of high capitalism, focuses on “the destructive element which authenticates both dialectical thought and the experience of the dialectical thinker.”30 When culture becomes a burden, its musealization and preservation only benefits the victors of history, the self-acclaimed owners and collectors of cultural heritage. And the “rulers at any time are the heirs of all those who have been victorious throughout history.”31 Benjamin’s historical materialism invokes its “destructive element” against this form and transmission of culture. Cultural history “may augment the weight of the treasure accumulating on the back of humanity, but it does not provide the strength to shake off this burden so as to take control of it.”32 Destroying, shaking off, taking control—these are the watchwords of a historical materialism that proves itself in adjusting to the “poverty of experience” and the untranslatability of tradition once capitalist modernity imposes and generalizes its own form of social relation—the commodity form. But what is the experiential counterpart of a capitalist world in which “all that is solid melts into air”?

In his essay on Baudelaire (1939), Benjamin argues that in capitalist modernity impartible experiences (Erfahrungen) have been replaced by a multiplicity of unmediated experiences (Erlebnisse). Drawing on this terminological difference33 and relying on Freud, he detects a shock defense mechanism with which the psychic apparatus shields itself from the penetrating power of the exposure to shock, the Chockerlebnis.34 This defense mechanism, however, is not only of a negative nature: experiences (Erlebnisse) are precise raw data of lived moments deprived of their impartible meaning. Erlebnisse are always assigned to an individual subject at an exact point in time, even if they have been experienced as a collective. Their trans-individual historical signature is no longer derived by the continuous transmutability of tradition but induced by fragmented shock experiences and socio-psychic interruptions, the collective medium of which Benjamin theorized in technological terms.

In the second version of his essay on The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility (1935–36) Benjamin hints at how the new technological medium of perception and experience could be conceived. He mentions a “second Technik”—a collective technique of using advanced technology in an emancipatory way.35 The goal of this second Technik is no longer “mastery over nature” like in the capitalist-exploitative “first Technik,” but a collective “‘interplay’ between nature and humanity.”36 In his 1928 book of aphorisms One-Way Street, Benjamin already warned that “man can be in ecstatic contact with the cosmos only communally. It is the dangerous error of modern men to regard this experience as unimportant and avoidable, and to consign it to the individual as the poetic rapture of starry nights.”37 The task of the post-humanist human is thus to construct a new technological medium for communal experiences (Erfahrungen) that exceeds the scope of individually fragmented Erlebnisse.38

However, against the ideological trends of late nineteenth century Lebensphilosophie and the vitalist “attempts to grasp ‘true’ experience [Erfahrung], as opposed to the kind that manifests itself in the standardized, denatured life of the civilized masses,” Benjamin assigned the realm of modernist experiences (Erfahrung) to a profane sphere.39 “Erfahrung is the outcome of work; Erlebnis is the phantasmagoria of the idler.”40 Without the constructive work of Erfahrung, there are only short-lived Erlebnisse. If the phantasmagorical revival of past Erfahrungen (Benjamin mentions “ideas that have come with the revival of astrology and the wisdom of yoga, Christian Science and chiromancy, vegetarianism and gnosis, scholasticism and spiritualism”41) only leads to flat Erlebnisse, the technologically constructed medium of actual Erfahrung cannot rely on a traditional stock of culturally transmitted knowledge or ripened wisdom. Rather, experience is a novelty—a new construction in and of the present, revealing a positive aspect of technological alienation. Hence, the task of forming the new medium of experience gets its cue from the world of fragmented Erlebnisse, a world of alienation and experiential emptiness, which Benjamin calls Erfahrungsarmut, or “poverty of experience.” The figure who has mimetically adjusted her life to the modern world of experiential poverty is the new barbarian—the one who acknowledges and estranges this poverty.

Arnold Schwarzenegger as Conan the Barbarian, dir. John Milius, 1982.

In the literary tradition of the early 1930s, the term “barbarism” was not solely reserved for fascism. Benjamin was not the only writer either who claimed the term in a non-pejorative sense. In December 1932—one year before Benjamin published “Experience and Poverty”—the American pulp fiction author Robert E. Howard invented the fictional character Conan the Barbarian, later adapted for cinema in 1982, kickstarting the career of Arnold Schwarzenegger. In Howard’s original fantasy story, The Phoenix on the Sword, Conan is a pre-historical mythic warrior who engages in various battles in the fictional kingdom of Aquilonia. Notably, Conan is depicted as an anti-idealist natural killer, devoid of all virtues and vices of civilization and its cynical sophistry.

What do I know of cultured ways, the gilt, the craft, and the lie? / I, who was born in a naked land and bred in the open sky. / The subtle tongue, the sophist guile, they fail when the broadswords sing; / Rush in and die, dogs—I was a man before I was a king.42

As a political observer of his time, however, Howard’s oeuvre is not limited to Conan and pulp fiction. In a letter to H. P. Lovecraft from December 1935, Howard wrote:

Your friend Mussolini is a striking modern-day example. In that speech of his I heard translated he spoke feelingly of the expansion of civilization. From time to time he has announced: “The sword and civilization go hand in hand!” “Wherever the Italian flag waves it will be as a symbol of civilization!” “Africa must be brought into civilization!” It is not, of course, because of any selfish motive that he has invaded a helpless country, bombing, burning, and gassing both combatants and non-combatants by the thousands. Oh, no, according to his own assertions it is all in the interests of art, culture, and progress, just as the German warlords were determined to confer the advantages of Teutonic Kultur on a benighted world, by fire and lead and steel. Civilized nations never, never have selfish motives for butchering, raping, and looting; only horrid barbarians have those.43

Wars fought in the name of “civilization,” along with liberal values of “progress,” fascist fantasies of supremacy, or Christian beliefs in “salvation” are the most violent ones and mobilize a monstrous sort of violence precisely for their “non-selfish,” quasi-idealistic ends. By implementing the violent rationale of civilization, that is, just ends can be met by violent means. Bourgeois and fascist anti-communisms rely on a similar logic, presenting the barbarian as domestic civilization’s externalized other who can be killed in the name of higher goals. While in the case of fascism, imperialism, and colonialism, this rationale is obvious, it is less visible in the case of liberal policies, particularly with the rise of international law in the late nineteenth century. However, one can argue with Perry Anderson that it precisely this liberal version of civilized war or war for civilization (nowadays called “war on terror”) that is the most dangerous and vicious one. Inverting a well-known dictum by La Rochefoucauld,44 Anderson writes: “Hypocrisy is the counterfeit of virtue by vice, the better to conceal vicious ends: the arbitrary exercise of power by the strong over the weak, the ruthless prosecution or provocation of war in the philanthropic name of peace?”45 Howard’s revaluation of the term “barbarian” does not only question the non-dialectical opposition of the concepts of “peaceful” Kultur and civilization on the one hand and “violent” barbarism on the other. It also demonstrates that the concept of barbarism itself allows for a transvaluation of the term, revealing its critical potential against the self-declared savior of Western civilization, namely fascism.

Setting aside Howard’s otherwise naive fantasy of barbarism as a prehistoric honest way of living prior to corrupting civilization, the idea of barbaric reduction as a critique of the modern myth of progress and Europe’s (and later the West’s) civilizing mission also plays a key role in Benjamin’s certainly different take on the barbarian. Benjamin characterizes the barbarian as a radical simplifier of life who can meet humanity’s basic needs rather than endlessly complicating them from the standpoint of bourgeois reason and its fictitious causalities. Benjamin’s “new, positive concept of barbarism” announces a new life-form, neither derived from a nostalgic past nor a prophetic future but from the poor now and the “dirty diapers of the present.”46 In accordance with the “Brechtian maxim: take your cue not from the good old things, but from the bad new ones,” the new barbarian articulates a post-humanist experience of impoverishment, proletarianization, and capitalist privation for which liberal-bourgeois humanism can no longer account.47 Radicalizing the decline of a premodern, presumably meaningful, cultural universe, Benjamin understands that the basic elements of a new form of experiential impartibility—one which is true to the challenges of the age of the machine, technological reproducibility, and capitalist commodification—can only be found after the status quo of an imposed material and experiential impoverishment is acknowledged in forthright terms.48

IV. Consequences: A Theory for Everyone and Nobody?

In preparation of his radio talk “Bert Brecht,” broadcast on Frankfurter Rundfunk in June 1930, Benjamin wrote a programmatic note in which he foreshadowed the figure of the modern barbarian and introduced a leitmotif of his future debates with Brecht:

Thought should become impoverished, it should only be permitted insofar as it is socially realizable. Brecht says: At least once people no longer need to think on their own, they are unable to think on their own anymore. But to attain an effective [wirksamen] social thought, people must give up their false and complicating wealth, namely the wealth of private assessments, standpoints, worldviews, in short the wealth of opinions. Here, we are touching upon exactly the same struggle against opinion in the interest of truth—against doxa—in which Socrates engaged two thousand years ago.49

The effectiveness of social thought is not measured by the logic of the marketplace and the cost-effective ratio of capital investment. Impoverishment, reduction, and dismantlement make social thought more effective—not improvement, progression, or accumulation. If, as Marx has it, the “wealth of societies in which the capitalist mode of production prevails appears as an ‘immense collection of commodities,’”50 poverty is the appearance of “thought which is rich in social consequences.”51 And in fact, “rich in consequences” (folgenreich) regarding both life and thought itself.52 But how are we to understand the antithetical convergence of wealth and poverty?

Benjamin’s critique of the liberal-bourgeois idea of democracy—namely the wealth of privately owned opinions that compete in a pluralistic way—touches the core of his take on Brecht and the limits of ideology critique. In the final version of his radio talk on Brecht, he put it succinctly:

Anyone who wants to define the crucial features of Brecht in a few words could do worse than confine himself to the comment that Brecht’s subject is poverty. How the thinker must make do with the few applicable ideas that exist; the writer, with the few valid formulations we have; the statesman, with the small amount of intelligence and energy man possesses: this is the theme of his work.53

Following Brecht and Benjamin, any theory of poverty must first impoverish itself. Thinking must reduce itself, must shrink its width and depth to meet poor reality. Yet such an economization of thought does not follow capitalist logic. Poverty is not a raw material, a stable state, or a given situation. It is a reductive procedure without a final goal. There is no zero-level of poverty; there are just different degrees and layers of impoverishment. If poverty is both the heteronomous condition of capitalist exploitation and the privation of human experience, Erfahrung, in general, poverty cannot be conceived of in “rich” terms.

Even the destructive or cathartic side of “thinking poorly” has constructive dimensions. In his undelivered talk “The Author as Producer” (1934), Benjamin defines “the most urgent task of the present-day writer” as that of recognizing “how poor he is and how poor he has to be in order to begin again from the beginning.”54 Beginning from the beginning necessitates the gesture of tabula rasa, clearing away the complicating wealth of opinions that stands in the way of new beginnings. However, the political board is always written and overwritten. There is no zero-level of (un)written doxa. There is only the movement of clearing away, rooting out. In his 1931 piece on “The Destructive Character,” Benjamin introduced a very peculiar form of destruction: “What exists he [the destructive character] reduces to rubble—not for the sake of rubble, but for that of the way leading through it.”55 The immediate, that is, noninstrumental medium of destruction is itself the path through the rubble, not for the sake of the rubble but for the sake of this path. Undoing the bourgeois wealth of doxa and pseudo choices is as liberating as it is destructive. It does not add another opinion, voice, or perspective, thus supplementing poor reality; rather, the reductive movement of undoing doxa by impoverishing thought is itself the articulation of a truth—the truth of a society in which social poverty and private wealth coincide.

The destructive character and the new barbarian, alike in their dismantling destruction, enact an effective interruption of bourgeois teleologies that allows for a radical simplification of life: “It must come as a tremendous relief to find a way of life in which everything is solved in the simplest and most comfortable way, in which a car is no heavier than a straw hat and the fruit on the tree becomes round as quickly as a hot-air balloon.”56 The relief from the weariness of an endlessly complicated life, subjected to the spurious infinity of neurotic overproduction in order to meet the most basic needs, has negative-utopian qualities. In the same vein, years later in his preparatory notes to “On the Concept of History,” Benjamin succinctly defines the “function of political utopia” as “to cast light on the sector of that worthy of destruction.”57

If theory must impoverish itself in order to traverse the poverty of experience, the figures of theory also need to de-figure themselves to meet poor reality. This reductive operation has its materialist grounds in the actually existing reductionism of capitalist exploitation and its experiential counterpart, the poverty of experience. Radicalizing this imposed impoverishment, the figure of the barbarian unleashes an asymmetric dialectics inside of the contradictory nature of their objects of criticism. It accelerates the process of its object’s decomposition while decelerating the creative-destructive explosion of a technology that modern capitalism has generated without having developed the necessary technique to master it. If the average European, as Benjamin notes in his essay on Karl Kraus, “has not succeeded in uniting his life with technology, because he has clung to the ideology of creative existence,”58 only figures like the new barbarian are ready to face this challenge without giving up on technology’s utopian space.59

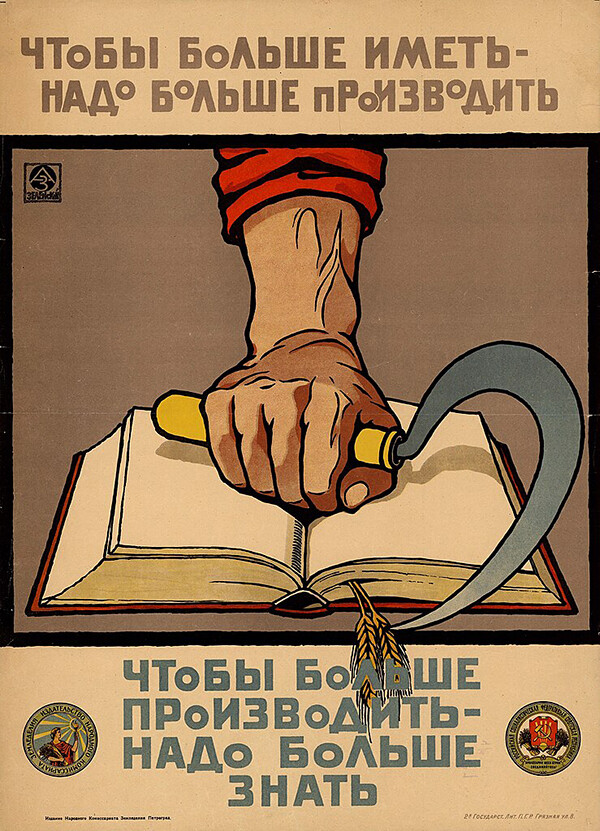

1920 propaganda poster: “In order to have more, it is necessary to produce more. In order to produce more, it is necessary to know more.” Alexander Zelensky, 1920. License: Public domain.

Such a new technological utopia or, rather, a-topia—a technological space beyond topical representation—can be found in the abovementioned second version of The Work of Art essay. The concept “second Technik” introduces an emancipated technology, which opens up a new Spielraum, room for play, beyond domination and instrumental relations between human and nonhuman nature. This Technik is not envisioned in a humanist-utopian manner; rather, it radicalizes the experience of capitalist alienation (Entfremdung) and experiential impoverishment. By denaturalizing capitalist teleologies, the new constellation of Technik, nature, and humanity estranges (verfremdet) the capitalist mode of alienation (Entfremdung).60 From the normative standpoint of historical progress, this constellation remains invisible and illegible—it is neither regressive nor progressive. Relying on the productive forces of capitalism only in a negative way, Benjamin’s concept of second Technik exploits the not-yet-fully-realized realities of advanced technology that capitalist modernity cannot put to work. In this sense, second Technik pursues the communist exploitation of unstable potentials that capitalism’s mode of exploitation not only fails to realize but seeks to obstruct.

Benjamin’s post-humanist figures of the age of technological reproducibility lack the gesture of Nietzsche’s Übermensch or the Promethean “New Soviet Man.” Impoverished figures like the new barbarian or the destructive character have no message or content—they are de-ideologizers without offering a new “critical” position. However, their promise of reductive simplification has never been put to the test. When reading Benjamin’s anti-historicist theory of legibility today, we are to ask: Who is the untimely, yet true, reader of these figures?61 What is the age that can recognize itself, that is, its own historical experience, in the unstable images of these figures? If the consequences of these figures point beyond their own historical horizon and place—Berlin and Paris in the early and mid 1930s—it is up to our age of “capitalist-realist” impoverishment to reconsider the truly historical moment of modern barbarism and destruction.62

To be sure, Benjamin’s irrefutable as well as unprovable diagnosis of Erfahrungsarmut, poverty of experience, poses a challenge to attempts to historicize it in the past. For what is the history of Erfahrung? Either there has never been a poverty of experience, or we cannot (yet) narrate, historicize it, and bury it in the past. It is impossible to determine the positive features of something we only “experience” in absence—as “poverty of.” Benjamin’s concept of experience, Erfahrung, remains speculative in the best non-positivist sense of the word. Its speculative ground, however, exceeds the speculations of theory. But what is left for the materialist intellectual who is to theorize the political, economic, social, and aesthetic conditions of poverty, deprivation, and precarity in the age of “very-late” capitalism? Eventually, Benjamin’s materialist argument comes down to a simple insight: the combination of poor experience and rich thought is poor in social consequences. “Truth is not to be secured through wandering, nor through collecting and adding up what is conceivable. Thinking must moreover at every stage and at each point always be repeatedly confronted with reality.”63 Instead of gradually enriching thought through inclusive multidirectionality, radical thought must insert reductive shortcuts, one-sided interruptions. In discussing Brecht, Benjamin affirms this sort of plumpes Denken, crude thinking, as a necessary counterpart to the richness of dialectical subtleties. “Crude thoughts have a special place in dialectical thinking because their sole function is to direct theory toward practice.”64

This re-edited essay contains sections of an earlier publication entitled “Barbaric Salvage: Benjamin and the Dialectics of Destruction” (Parallax 24, no. 2, 2018). A different version was presented at MAMA Multimedijalni institut, Zagreb, on February 27, 2015. I thank Anne van Leeuwen, Nadia Bou Ali, Mark Hayek, and Petar Milat for their comments and critical remarks on earlier versions. My argument is indebted to the works of Benjamin Noys and Irving Wohlfarth, and discussions during the workshop “Nihilism, Destruction, Negativity: Walter Benjamin and the ‘Organization of Pessimism’” at Jan van Eyck Academie, Maastricht, on December 6, 2012. All mistakes and misreadings, however, are mine.

Walter Benjamin, Selected Writings, ed. Marcus Bollock and Michael W. Jennings, vol. 2.1 (Belknap Press, 1999), 367.

Walter Benjamin, Gesammelte Schriften, ed. Hermann Schweppenhäuser and Rolf Tiedemann, vol. 7 (Suhrkamp, 1989), 655.

Benjamin, Selected Writings, vol. 2.1, 367; Walter Benjamin, Gesammelte Schriften, ed. Hermann Schweppenhäuser and Rolf Tiedemann, vol. 2 (Suhrkamp, 1977), 662.

Benjamin, Selected Writings, vol. 2.1, 367.

Bertolt Brecht, Stories of Mr. Keuner, trans. Martin Chalmers (City Lights Books, 2001), 10.

Walter Benjamin, “On Theoretical Foundations: Theses on Brecht,” Radical Philosophy, no. 179 (2013): 28.

Walter Benjamin, Selected Writings, ed. Marcus Bollock and Michael W. Jennings, vol. 2.2 (Belknap Press, 1999), 732.

Benjamin, Selected Writings, vol. 2.2, 732.

Marx’s technical term for this sort of capitalist root extraction is “abstract labor,” the transformation of living labor into the spectral, that is the “sensuous-supra-sensuous,” materiality of value. See Marx, Capital, vol. 1 (Penguin, 1990), 138f.

Benjamin, Selected Writings, vol. 2.2, 732.

Benjamin, Selected Writings, vol. 2.2, 735.

Benjamin, Selected Writings, vol. 2.1, 217f.

Walter Benjamin, Selected Writings, ed. Marcus Bollock and Michael W. Jennings, vol. 4 (Belknap Press, 2003), 402.

See the film The Matrix, dir. Lilly and Lana Wachowski, 1999. The complete formula “Welcome to the Desert of the Real” became famous through Slavoj Žižek’s same-titled book, Welcome to the Desert of the Real: Five Essays on September 11 (Verso, 2002).

According to Barbara Cassin’s reading of the Sophists, this binary had already been undermined and denaturalized in Ancient Greece. Cassin, “Sophists,” in Greek Thought: A Guide to Classical Knowledge, ed. Jacques Brunschwig and Geoffrey E. R. Lloyd with the collaboration of Pierre Pellegrin (Belknap Press, 2000), 969f.

John Wesley Powell, “From Barbarism to Civilization,” American Anthropologist 1, no. 2 (1888): 98.

Powell, “From Barbarism to Civilization,” 121.

Max Horkheimer and Theodor W. Adorno, Dialectic of Enlightenment, trans. Edmund Jephcott (Stanford University Press, 2002), 50.

Horkheimer and Adorno, Dialectic of Enlightenment, 169.

Horkheimer and Adorno, Dialectic of Enlightenment, 11, 4, xviii.

Rosa Luxemburg, The Junius Pamphlet: The Crisis of German Social Democracy, 1915, marxists.org →.

In thesis thirteen in “On the Concept of History,” Benjamin criticized the bourgeois concept of progress, maintained by vulgar Marxism and Social Democracy: “Social Democratic theory and to an even greater extent its practice were shaped by a conception of progress which bore little relation to reality but made dogmatic claims. Progress as pictured in the minds of the Social Democrats was, first, progress of humankind itself (and not just advances in human ability and knowledge). Second, it was something boundless (in keeping with an infinite perfectibility of humanity). Third, it was considered inevitable—something that automatically pursued a straight or spiral course. Each of these assumptions is controversial and open to criticism” (Benjamin, Selected Writings, vol. 4, 394). This criticism was later echoed in Adorno’s Minima Moralia (1951). Despite the decline of the Social Democratic belief in progress, the determinist belief in objective laws of history and economy remained intact. Even catastrophic regresses in history were taken as driving forces of progress: “Cured of the Social-Democratic belief in cultural progress and confronted with growing barbarism, Marxists are under constant temptation to advocate the latter in the interests of the ‘objective tendency,’ and, in an act of desperation, to await salvation from their mortal enemy who, as the ‘antithesis,’ is supposed in blind and mysterious fashion to help prepare the good end.” Adorno, Minima Moralia: Reflections On a Damaged Life, trans. E. F. N. Jephcott (Verso, 2005).

Benjamin, Selected Writings, vol. 4, 392.

I owe this insight to Maria Boletsi’s excellent study Barbarism and Its Discontents (Stanford University Press, 2013), 117–21.

I borrow this apt translation from Boletsi, Barbarism and Its Discontents, 123.

Benjamin, Selected Writings, vol. 2.2, 732.

Walter Benjamin, Selected Writings, ed. Marcus Bollock and Michael W. Jennings, vol. 3 (Belknap Press, 2002), 144.

Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, The Manifesto of the Communist Party, ed. David Harvey (Pluto Press, 2008), 38; cf. Marshall Berman, All That Is Solid Melts Into Air: The Experience of Modernity (Penguin, 1988), 15–36.

Benjamin, Selected Writings, vol. 3, 268.

Benjamin, Selected Writings, vol. 4, 406.

Benjamin, Selected Writings, vol. 3, 268.

Since this difference gets lost in the English language (Erlebnis and Erfahrung are both translated as “experience”), I have added the German word whenever I refer to “experience.”

Benjamin, Selected Writings, vol. 4, 318; cf. Benjamin, Gesammelte Schriften, ed. Hermann Schweppenhäuser and Rolf Tiedemann, vol. 1 (Suhrkamp, 1974), 614.

Benjamin, Gesammelte Schriften, vol. 7, 360. The German word “Technik” denotes both technique and technology. The English edition only refers to “technology,” cf. Benjamin, Selected Writings, vol. 3, 107.

Benjamin, Selected Writings, vol. 3, 107–8.

Walter Benjamin, Selected Writings, ed. Marcus Bollock and Michael W. Jennings, vol. 1 (Belknap Press, 1996), 486.

In his essay on French surrealism, Benjamin introduces the paradoxical concept of “profane illumination,” which provides the theoretical ground to combine the otherwise antithetical concepts of sober technology and ecstatic communal experiences. Benjamin, Selected Writings, vol. 2.2, 207–8. Cf. M. Cohen, Profane Illumination: Walter Benjamin and the Paris of Surrealist Revolution (University of California Press, 1993); and Rainer Nägele, “Body Politics: Benjamin’s Dialectical Materialism between Brecht and the Frankfurt School,” in The Cambridge Companion to Walter Benjamin, ed. David S. Ferris (Cambridge University Press, 2004).

Benjamin, Selected Writings, vol. 4, 314.

Walter Benjamin, The Arcades Project (Belknap Press, 1999), 801, trans. modified. I owe this quote and its relevance for Benjamin’s theory of Erfahrung to Jacob Bard-Rosenberg.

Benjamin, Selected Writings, vol. 2.2, 732; cf. Benjamin, Gesammelte Schriften, vol. 2, 215.

Robert E. Howard, “The Phoenix on the Sword,” in Weird Tales, December 1932 →. Epigraph to the fifth chapter.

Robert E. Howard, “Letter to H. P. Lovecraft, December 5, 1935,” in The Barbaric Triumph: A Critical Anthology on the Writings of Robert E. Howard, ed. Don Herron (Wildside Press, 2004), 175.

“L’hypocrisie est un hommage que le vice rend à la vertu.” (Hypocrisy is a tribute that vice pays to virtue).

Perry Anderson, “The Standard of Civilization,” New Left Review, no. 143 (September–October 2023.

Benjamin, Selected Writings, vol. 2.2, 733.

Benjamin, Selected Writings, vol. 3, 341.

Cf. Esther Leslie’s reading: “Impoverished experience can be overpowered only if the fact of poverty is made into the underpinning of a political strategy of a ‘new barbarism’ that corresponds faithfully to the new realities of the constellation of Masse and Technik.” Leslie, Walter Benjamin: Overpowering Conformism (Pluto Press, 2000).

Walter Benjamin, “On Theoretical Foundations: Theses on Brecht,” Radical Philosophy, no. 179 (2013): 28.

Marx, Capital, 125.

Benjamin, “On Theoretical Foundations,” 28, trans. modified.

Benjamin, “On Theoretical Foundations,” 28, trans. modified.

Benjamin, Selected Writings, vol. 2.2, 370.

Benjamin, Selected Writings, vol. 2.2, 776.

Benjamin, Selected Writings, vol. 2.2, 776.

Benjamin, Selected Writings, vol. 2.2, 735.

Translation mine. Compare the German: “Funktion der politischen Utopie: den Sektor des Zerstörungswürdigen abzuleuchten.” Benjamin, Gesammelte Schriften, vol. 1, 1244.

Benjamin, Selected Writings, vol. 2.2, 456.

In the same passage, Benjamin also enlists Adolf Loos and “his struggle with the dragon ‘ornament,’” the “stellar Esperanto of Paul Scheerbart’s creations,” and “Klee’s New Angel.” Benjamin, Selected Writings, vol. 2.2, 456.

Benjamin mentions three forms of technological alienation, Entfremdung: (1) In the case of surrealist photography he speaks of a “salutary estrangement (heilsame Entfremdung) between man and his surroundings” (Selected Writings, vol. 2.2, 519; Gesammelte Schriften, vol. 2, 379). (2) In terms of the advanced Technik of cinema and film production, he states that the “representation of human beings by means of an apparatus has made possible a highly productive use of the human being’s self-alienation (Selbstentfremdung)” (Selected Writings, vol. 3, 113; Gesammelte Schriften, vol. 7, 369). (3) Speaking of imperialist wars and the fascist “aestheticizing of politics,” Benjamin remarks that humanity’s “self-alienation (Selbstentfremdung) has reached the point where it can experience (erleben) its own annihilation as a supreme aesthetic pleasure” (Selected Writings, vol. 3, 122; Gesammelte Schriften, vol. 7, 384). To keep the terminology consistent, I suggest using the Brechtian term Verfremdung, “estrangement,” for the (potentially) emancipatory impact of modern Technik; estrangement is a denaturalizing technique of undoing technology’s capitalist usage and discovering the potentials of second Technik. I refer to the early Marxian and Hegelian term Entfremdung, “alienation,” only when I highlight technology’s (potentially) negative or depriving results. This distinction can be broadly mapped on Benjamin’s differentiation in first and second Technik. As in the case of first and second Technik, the distinction of estrangement and alienation is not absolute; they are always mixed and present extreme poles of a dialectical relation.

Such an anachronic question exceeds the horizon of attempts to historicize Benjamin and read him only in the context of the avant-garde tendencies of the 1920s and the “Culture of Distance in Weimar Germany.” See Helmut Lethen, Cool Conduct: The Culture of Distance in Weimar Germany, trans. Don Reneau (University of California Press, 2002).

I am referring here to Mark Fisher’s title Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative?, according to which postmodern capitalism “seamlessly occupies the horizons of the thinkable.” Fisher, Capitalist Realism (Zero Books, 2009), 8.

Benjamin, “On Theoretical Foundations,” 28.

Walter Benjamin, “Brecht’s Threepenny Novel,” in Walter Benjamin: Selected Writings, vol. 3, 1935–1938, ed. Marcus Paul Bullock and Michael William Jennings (Belknap Press), 7.