Ah! Earth, talk to me, make me hear your voice! I no longer recall your voice! Sun, talk to me! Where’s the place from which I can hear your voice? Earth, talk to me; sun, talk to me. Perhaps you’re getting lost in order to not ever return? I no longer hear what you say! You, grass, talk to me! You, stone, talk to me! Where is your sense, earth? Where can I find you again? Where’s the bond that joined you to the sun? I touch the earth with my feet and I don’t recognize it! I look at the sun with my eyes and I don’t recognize it!

—Pasolini, Medea, 1969

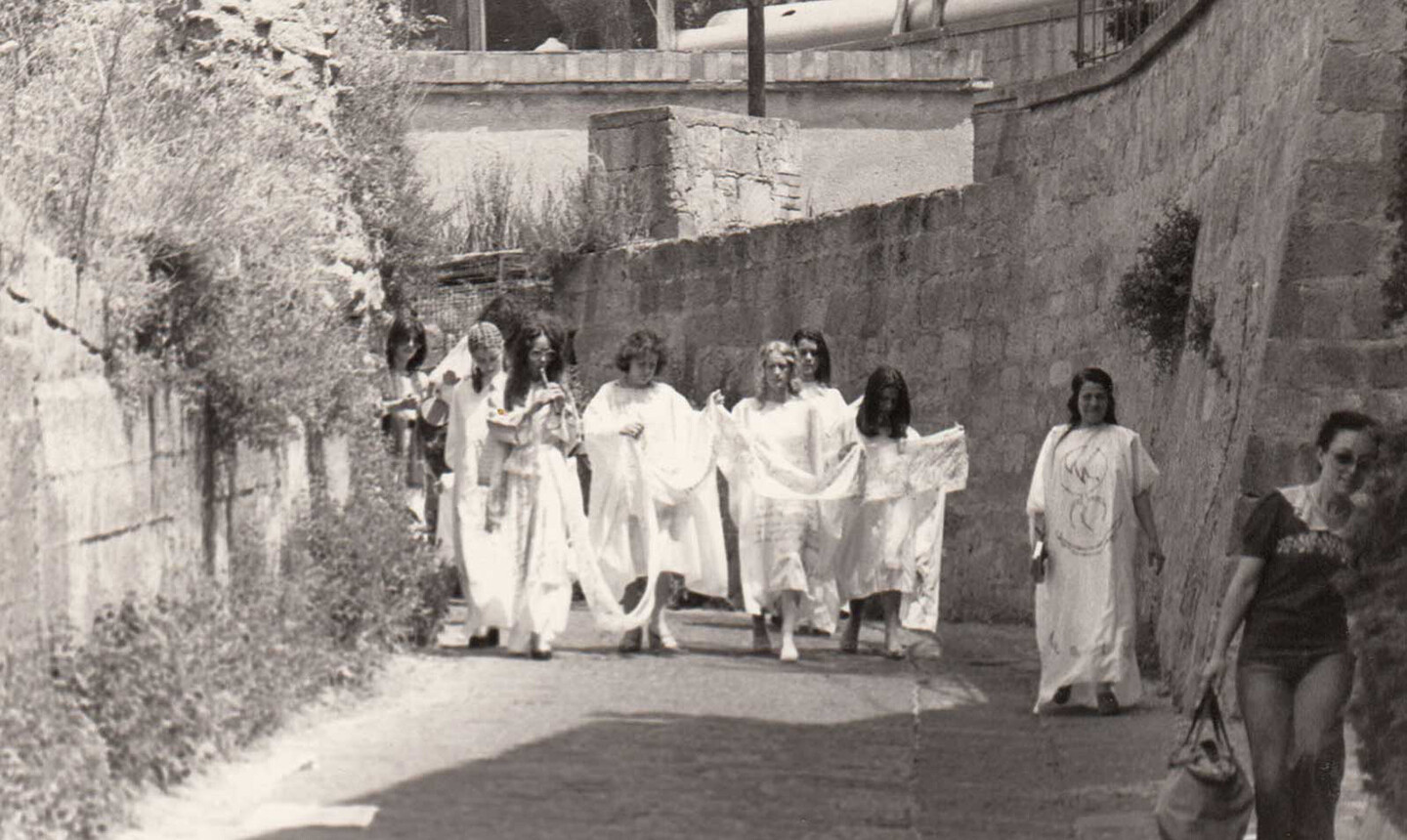

In this cosmological and prophetic exclamation, the mythical Medea (as played by Maria Callas in Pasolini’s eponymous 1969 film) stages her erotic and tragic struggle. Medea is a prophetess, descendant of the Amazons, granddaughter of Sun, a sorceress who transforms gory and violent acts into reflections of the sacred. Before uttering these words in the film, she used her magic powers to help Jason find and retrieve the golden fleece. As a result, she was forced to abandon her kingdom, kill her brothers, and leave for Corinth. A lot of sacrifice to facilitate Jason and the Argonauts’ escape.

As she utters this imprecation (spoken curse), Medea comes to grips with the fact that her world is incompatible with Jason’s. Her home Colchis, full of sacred meanings, is already behind her. Corinth, however—where she arrives while marveling at a new foreign sun—is governed by different logics, a different reason even. In his film, Pasolini uses these two epistemologies as metaphors for his own poetic speculations. As in his many films, critical writing, poems, and novels, he stages the unresolved relationship between the poor and sub-proletarian world and the historically constructed bourgeois world based on hetero-patriarchal reason. As recent writing on Pasolini has emphasized, this duality also corresponds to the relation between the (Global) North and the (Global) South, between modern homogeneity/individuation and heterogeneous collectivity, a vision that is too often essentialized in a liberal framework and for which History as it exists offers no possibility for reconciliation. Since the onset of modernity, this vulnerable and oppositional matrix has captured—or “enclosed,” in the language of feminist theory—human beings within the linear logics of patriarchal and racialized capitalism.

In this text, I follow a question posed by Denise Ferreira da Silva, who wonders what would happen if, instead of ordering the world through separability, determinacy, and sequentiality, we instead used poesis to disrupt the “Ordered World.”1 To do so, I consider feminist mythology as an “art of interruption” that can recast space, chronology, and subjectivity by looking to situated art and political practices that are both pragmatic and speculative. As Chiara Bottici writes: “Myths are self-fulfilling prophecies: they do not wait for reality to prove their truth, they just go ahead and build it.”2 In particular, feminist mythical narratives point to forgotten memories, historical amnesia, and entangled forms of dispossession that in their invocation reject linear time lines of development and progress. Instead of the secular “strength-thinking, verb-thinking” that underpins the univocal cosmology of Western liberal history, I look at the critical and enchanted artistic practice of the Neapolitan feminist collective Le Nemesiache to identify pathways toward the speculative reappropriation of the “mythological thought, oracular reality and clairvoyance of a mythical sibylline philosophy.”3

Putting Myth Back into the World

In 1969, the same year as Pasolini’s Medea, Lina Mangiacapre returned to Naples after she had participated in the large 1968 student movements in the north of Italy. She had graduated with a degree in philosophy but since the revolts had devoted herself to painting under the pseudonym Màlina. Back in her hometown, energized surely by the magnitude of student and worker uprisings that would inaugurate a decade of country-wide insurgency, she cofounded the feminist collective Le Nemesiache (named for the goddess Nemesis), which had a clear goal: they “intended to bring myth back into the world.”4

Pier Paolo Pasolini, Medea, 1969.

As researcher, curator, and performer Giulia Damiani, who has extensively researched the group, has pointed out: “Although its composition has varied throughout the decades, the collective has been said to have been animated by up to twelve women at times,” including Lina Mangiacapre, Teresa Mangiacapre, Bruna Felletti, Conni Capobianco, Claudia Aglione, Fausta Base, and Silvana Campese.5 They came together the same year that the better-known Italian feminist group Rivolta Femminile (Female Revolt) was founded by Carla Lonzi, Carla Accardi, and Elvira Banotti. Le Nemesiache’s manifesto was written in 1970 (like Rivolta Femminile’s) but wasn’t published until 1972. The comparison is a generative one, as the groups proposed very different strategies that point to the divergent threads of Italian feminist theory and praxis that have been typically flattened into a singular story of postwar feminism. Though the feminist struggle was nominally the same across the board—women’s liberation from patriarchal dominance—the respective approaches of these groups demonstrate the variegated nature of Italian feminisms in the post-’68 years.

During the seventies in Italy, the women’s movement had to fight two battles. It had to stake out its own autonomy from the institutionalized left and the student movement, which both relegated feminism to the background; and it had to organize at the wider community level, on the streets.6 Indeed, the many feminist groups that sprang up in that period found themselves divided between practices geared towards the “outside” (such as family counseling and street theater groups) and the “inside” (such as consciousness-raising and experiments in communal living).7 While Rivolta Femminile, for example, were committed to a radical refusal of the outside and turned toward a deep-rooted exploration of the inside, Le Nemesiache instead attempted to integrate both practices, transcending institutional formations and embedding themselves in the materiality of life, while working to disrupt the division between public and private that is so central to the capitalist division of labor. As they write in their manifesto:

It is necessary to doubly multiply the struggle; outwardly, to condemn and denounce all the violence that women suffer; inwardly, to study all the dimensions and spaces that women have created for themselves and to foster the creation of new ones … In every woman there is that inner dreamworld that is rejected by society … It is this dimension that we want to revive by recovering and affirming it.8

Cenerella was the first play written and directed by Lina Mangiacapre. Staged in 1973 in Naples.

As evidenced in this document, Le Nemesiache began from the development of a new “metaphysics of struggle,” to borrow from M. Jacqui Alexander, who argues that the search for beauty and the search for social justice can coexist, and that political commitment and fabulation co-occur.9 The group articulated what we might call a “sacred wholeness” that was otherwise erased by secular powers. “We shall invent and create our struggle, as we will with our sexuality and our culture,” they continue in their manifesto. “The new dimension or, let’s say, new metaphysics, turns everything upside down, and our creativity is our world, which emerges and explodes by turning it upside down and discovering infinite fantastic unpredictable dimensions.”10 In short, from the outset they expressed an awareness that the cosmos can and must be reimagined.

Their practice foregrounded emotional liberation through experimentation with multiple forms of cultural production that challenged gender and professional categorization. While Rivolta Femminile adopted writing-based consciousness-raising tactics to disrupt female subjectivity within the patriarchal “discourse of culture,”11 Le Nemesiache introduced what they called the psico-favola (psycho-fable), in which they rewrote existing folktales and myths from a feminist perspective. Thus, stories that were otherwise relegated only to prayers, places of worship, and to antiquity were reappropriated to be used as means of expression and communication to catalyze self-determination and collective liberation. With the psycho-fable, they write, “all repression made to women’s emotionality and their bodies explodes.”12

Their collective rewriting of tales and mythologies aimed to transform the unexpressed voices of suffering worlds (both women’s bodies and ecological landscapes) into stories of resistance and settings for liberation. For instance, their work Cenerella, the first expressly feminist Italian play, was a medieval Campanian version of Cinderella, based on Giambattista Basile’s original 1630 version. The play was staged in 1972 in Naples and Milan, then in 1975 in Amalfi. (They later adapted the work into a film.) In the transposed story, the protagonist breaks away from the canonical role of a woman confined to marriage and in perpetual search of her “prince.” The fantastical figure of Attanurreta, the fairy witch who helps Cenerella and personifies the possibility of destituting the domesticated symbolic order of traditional narratives, opens a space for the invocation of bodily revelations. With works like this, Le Nemesiache was able to stage, in the words of Lina Mangiacapre, the transformation “from pain to consciousness, to denunciation, to revolt.”13

The singular position occupied by Le Nemesiache within broader Italian—and more generally European—artistic feminism of the 1970s and ’80s lies in their metaphysics of struggle, which addresses oppression distributed on multiple levels, namely “the essentialist utopia of nature, the organization of labor (productive and reproductive), and the male privilege of creativity.”14 To address these intersecting forms of subjugation, the group built a practice that went beyond commodity critique or the critique of the alienation of cultural labor. Indeed, in the context of this essay in an art magazine, it is difficult to capture the group’s dynamism without objectifying or disenchanting it. As Mangiacapre asked: “Why do we [feminists and critical thinkers] move from the mythical form to the conceptual? … What is it that you attempt to forget?”15 Mangiacapre recognized how even logic could be a threat to women’s liberation. Thus, for Le Nemesiache, this liberation depended on women’s creative self-determination, and myth was key to this process.

A New Common Metaphysics

Le Nemesiache’s use of myth was not restricted to storytelling. Their psycho-fables intersected with living political resistance. As Mangiacapre wrote: “Myth was this form where the body” signals the importance of embodied, personal knowledge in artistic and political experimentation.16 Rejecting key foundations of Western thought—specifically the model of a universal subject and the binary between nature and culture—the group’s struggle intersected with ecology, social justice, labor, housing, and health issues. As one example of their intersectional approach to the liberation of women, in 1981 they participated in the organization of a major conference titled “Ricostruiamo una città a dimensione donna” (Let’s rebuild the city to female dimensions), which was attended by six hundred women. The year before, an earthquake had devastated the area around the village of Castelnuovo di Conza in Campania. At the conference, attendees discussed the gendered distribution of the humanitarian relief effort from women’s points of view, examining the economic, political, and social marginalization of the affected area through the lens of uneven infrastructural development. As the group argued in a related text: “The feminist struggle for the right to one’s sexuality as creativity is combined with the struggle for the right to one’s origins and roots. No more being forced to emigrate! Our beauty and art must not continue to be destroyed by being condemned to survival.”17

“Let’s rebuild the city to female dimensions.” Neapolitan feminist movement, 1981. Courtesy of Le Nemesiache.

As evidenced by this conference, Le Nemesiache’s projects were fervently interdisciplinary, encompassing film, performance, critical writing, painting, poetry, music, collage, and costumes. However, in addition to erasing the barriers between different disciples of creative and intellectual production, their work also sought to reconnect political action and cultural production. During the seventies and eighties, they organized political interventions into the built environment, such as the two-year occupation of the Ospedale Psichiatrico Frullone, a psychiatric jail for women outside of Naples. Le Nemesiache collaborated with incarcerated women on the occupation, and the experience later gave rise to the group’s film Follia come poesia (Madness as poetry, 1979). In the film, incarcerated women express themselves through music, movement, and clothing, rejecting the stigmas of both incarceration and “madness.” Another striking example of the group’s effort to erode the boundary between art production and political activity was a 1977 action they called “Occupazione ‘Salvator Rosa’ (Casina Pompeiana).” For this action, Le Nemesiache took over a building that had been founded by liberal artists during the Bourbon occupation of Naples (1734–1861). The choice to occupy this building was also symbolic: it was a demand for genuinely collective and public “space for sharing and creation.” Le Nemesiache took action to defend public space, while bringing practices of commoning into artistic discourse and urban political action, anticipating contemporary discussions on art, feminism, and the commons.

With the goal of centering the feminine at the heart of their (political and artistic) action, Le Nemesiache founded a feminist film festival that ran between 1976 and 1994 in the Neapolitan coastal town of Sorrento. Called Rassegna del Cinema Femminista (Festival of Feminist Cinema), the festival was expressly organized as a counter-festival within the framework of the larger festival Incontri Internazionali del Cinema (International Cinema Encounters). Unlike major festivals for avant-garde cinema at the time (Cannes, Berlin, Venice, etc.), Rassegna del Cinema Femminista centered work by women and nonprofessional filmmakers, aiming to stimulate debate and discussion on transnational feminist questions.

Through such events, Le Nemesiache sought to repurpose spaces (whether cinemas or occupations) to become active consciousness-raising sites as well as spaces for experimenting with collective forms of production and life. Le Nemesiache refused the professionalism and rigid division of labor inherent to production in the film industry. For the films that showed at Rassegna del Cinema Femminista, the group produced costumes, lights, and soundtracks on their own. Every element was created collaboratively and according to artisanal approaches that refused the hierarchy between fine and craft arts.

The group’s practices were attuned to both a material and metaphysical analysis of space.18 In their 1973 Manifesto metaspaziale (Meta-spatial manifesto), for example, they write: “Beyond the boundaries of the space in which one lives … arises the desire to trace and connect close women, by which we mean women who have critically placed themselves beyond cultural barriers, and who can also be affected by situations that take place in a distant physical space.”19 Anchoring and transcending space at once, what emerges here is similar to what postcolonial theorist Gayatri Spivak later defined as “planetary ethics,” by which she meant the possibility to reimagine common relations, tracing and retracing alternatives to patriarchal and colonial logics.20 Such alternatives are particularly evident in the group’s awareness of the limits of gender; they distance themselves from an essentialist figuration of feminist subjectivity, thus prefiguring intersectional strategies such as those advocated by transfeminism. Indeed, this latter term was already used by Lina Mangiacapre in the eighties to call for a new humanity positioned against the man/woman binary. Mangiacapre called instead for an androgynous sexuality. Le Nemesiache advanced this view in a political action in Naples in 1982. During an institutional journalism conference, the group broke into the conference space dressed in traditionally masculine clothing, shouting that “it isn’t only about modern man and modern woman anymore, but about giving rise to a mutating being, whose sexual identity will metamorphose continually.”21

Fabulating Memory

In her novel Faust/Fausta, Lina Mangiacapre writes: “Remembrance is cut off by the law of fathers … Mothers lead me to make gestures, to know places, to know experiences that I never wanted to try, that I rejected by taking fathers’ heads.”22 In Le Nemesiache’s gestures, Mangiacapre found the traces of a different humanity, a conduit of feelings and fantasies connecting all the elements of the natural world and a maternal lineage. As already mentioned, this opens towards an ecological perspective. The group expressed a co-belonging with the sea, the rocks, the Vesuvius volcano, and its lava, showing that rocks, land, and water hold memories.

Le Sibille, directed by Lina Mangiacapre and produced by Le Nemesiache, 25 min, 1977. Courtesy of Le Nemesiache.

Thus, Le Nemesiache’s praxis didn’t only concern feminist collective organization or the urban. It also staked out a political reality rooted in the geological territory of Naples and its surroundings. The group’s fabulation of the ancient through the territory is intimately connected to the female oracle Sybil, who presided over the Apollonian oracle at Cumae near Naples. With their film Le Sibille (1977), Le Nemesiache denounced the historical expropriation of territory. The film suggests that the colonizing shadow of Western media culture obscures and alienates local identities and histories in which oral culture, myth, nature, animality, imagination, magic, and fantasy are intertwined, especially in Southern Italy. As Mangiacapre wrote, “There is still a trace of these roots, in us, in the archaeological ruins, in the magic of revisited places, in the subculture of certain prediction that still exists in the old women of Naples; the journey is possible.”23 Sybil was mobilized in the group’s work to rethink cosmological knowledge but also to speculate on radical futures from an ecological perspective. In the film, bodily movements performed by a group of women enact self-liberation and collective invocation toward a nonlinear temporality of remembrance. At the beginning of the film, for example, an old woman reading tarot cards is invoked to lament historical witch hunts. The group’s cinematic expression coalesces with an embodied will in a movement towards freedom, creating a tension between natural and choreographic movement, documentary and fiction.24

In the film, the different figures who stand in for alternate versions of the oracle Sybil revolt against linear temporality by coming back into the present to restore old, marginalized knowledges. By embodying temporalities different from the present, these figures confabulate with spiritualities other than those of the colonial project, struggling for an experience of the cosmos lived by those on the spatial and cosmological margins of Europe. Sybil, Naples, the siren Partenope, and the lava of Vesuvius became coauthors that rewrite mythologies. Le Nemesiache introduced a

fluctuating frontier that breaks with given sexual identities … Androgyny makes use of a force that women have abounded … An androgynous thought is a thought that has its absolute force in the present, but that is capable of recreating the past, reaffirming and reliving the myth, and recreating the future.25

The Amazon as the mythological personification of transfeminism and androgyny was the stated basis for Mangiacapre’s artistic and philosophical approach precisely because “sexual difference is introduced by man as the birth of the concept and with the killing of the Amazons.”26 Orchestrated by Nemesis (the Greek goddess of revenge), a new cosmology erupts, “returning to mythical thought, returning to Mnemosyne [the goddess of memory] … and the scandal of difference, the consciousness and the splitting of nature from the cosmos.”27 In Le Nemesiache’s practice, memory becomes a technique of imagination, and history becomes a metamorphic process interconnected with the surrounding landscape in which the self is immersed and enriched. The natural world holds a key to a collective consciousness buried deep in the geomorphic environment, in archeological ruins, and in mourning that women have conjured in rituals throughout time.

The Past Within Us

In contrast to an Italian feminism based on the theorization of difference, Le Nemesiache introduced sensual, ecological, hospitable, and transformative dimensions, proposing what we might call an interdependent planetary architecture that embraces cosmic and poetic alliances. As cosmonauts—with joyful fugitivity from their present—the group modeled a relational world-making rooted in Naples that could expand planetarily, avoiding the trap of the usual folklorization of a subaltern city, pointing instead to internationalist class struggles. Le Nemesiache’s “warrior function,” mythologically personified in the Amazons, recomposes the boundaries that determine the self and the other, inside and outside, here and there, embodying epistemic breaks and paradigmatic changes towards a new metaphysics, a new humanity whose sexual identities will metamorphose continually. As Mangiacapre wrote:

To denounce the phallic mystification of an anthropocentric theory that in justifying itself as human excluded a part of humanity; this meant for feminism to carry out in practice a real revolution … to question the overall validity of any ideology which, however universal, because it was produced by a part of the species could not but be more or less consciously sexist.28

For Le Nemesiache, “memory begins with an imagined world.”29 In the invocation at the beginning of this text, Medea has left behind her land—the land of Amazons and witches as well as of her knowledge, magic mastery, and power—to give life. In Cenerella, the sorceress-fairy Attanurreta comes to Cinderella’s aid to free her from the trap of the prince and the slipper. But this also restores Cinderella as an Amazon, restores Medea-woman before her encounter with Jason. Mangiacapre described it this way: The Amazons were killed by the Greeks, who ostracized the “magic” of women. But Le Nemesiache’s counter-use of the Amazons myth resists the modern category of essentialist female figuration.

In her analysis of the witch hunts that accompanied capitalist primitive accumulation, Silvia Federici speaks about the “enclosure” of women’s bodies. Le Nemesiache’s practice could thus be thought of an act of “disenclosure.” Federici suggests that “parallel to the history of capitalist technological innovation we could write a history of the disaccumulation of our pre-capitalist knowledges and capacities”—a “disaccumulation” on which capitalist civilization is built.30 Medea herself represents the struggle against the process of civilization, and the tragic love story between her and Jason evokes the oppositional cosmologies of barbarism and civilization. The latter relegates to legends and mythology cultures other than Western bourgeois humanism, as metaphorically highlighted by Pasolini’s film and by Le Nemesiache’s films and performances. In Pasolini, the narration still embodies an unsolved dualism, an attempt to update the old plot of the myth. By contrast, Le Nemesiache’s films center their philosophical and creative practice in the body and emotions, rearticulating ways of thinking the mind and the body, the individual and community, the secular and the spiritual. If Carla Lonzi’s feminism “imagined an autonomy that seems only to be possible at the level of the interior self,” Le Nemesiache, with their focus on the body and their poetics of the flesh, proposed another cosmology.31 By putting myth back into the world, Le Nemesiache’s project proposed that

to discover the unity of the suns of our struggles was to return to the cosmic sky of all the seas,

of suns and moons through the tides of blood, the lava of the volcanoes, the burning of all witches,

to return to myself and all my relationships, to construct a history of all time, history as life, as harmony, as 0.32

Denise Ferreira Da Silva, “On Difference Without Separability,” in Incerteza Viva (Bienal São Paulo, 2016). Exhibition catalog.

Chiara Bottici, A Feminist Mythology, trans. Sveva Scaramuzzi and Claudia Corriero (Bloomsbury Publishing, 2001), 17.

Lina Mangiacapre, Cinema al femminile 2 (Female cinema 2) (Le Tre Ghinee/Le Nemesiache, 1994), 1, 2. Unless otherwise specified, all translations are by the author.

Silvana Campese, La Nemesi di Medea: Una Storia Femminista lunga mezzo secolo (Medea’s nemesis: A half-century feminist story) (L’Inedito, 2019), 36.

Giulia Damiani, “Archival Diffractions: A Response to Le Nemesiache’s Call,” in Over and Over and Over Again: Reenactment Strategies in Contemporary Arts and Theory (ICI Berlin Press, 2022), 82.

As Enda Brophy writes, the feminist movement in Italy also “directed its antagonistic critique beyond the role of the State to the male-dominated Italian left, including the radical workerist left … The most symbolic and public moment occurred in Rome on December 6th, 1977, when the male stewards of Lotta Continua and of the Comitato Autonomo di Centocelle attacked a feminist demonstration and its vindication of a woman’s right to separate from a man.” Enda Brophy, preface to Giovanna Franca Dalla Costa, The Work of Love (Autonomedia, 2008), 8.

Maud Anne Bracke, Women and the Reinvention of the Political: Feminism in Italy 1968–83 (Taylor and Francis 2014), 67–68.

“Manifesto delle femministe napoletane: Le Nemesiache, 1970” (Manifesto of Neapolitan feminists: Le Nemesiache, 1970), in Interpreti e protagoniste del movimento femminista napoletano 1970–1990 (Interpreters and protagonists of the Neapolitan feminist movement 1970–1990), ed. Conni Capobianco (Le Tre Ghinee/Le Nemesiache, 1994).

M. Jacqui Alexander, Crossing Pedagogies: Meditations on Feminism, Sexual Politics, Memory, and the Sacred (Duke University Press, 2006), 275.

“Manifesto delle femministe napoletane.”

Feminism and Art in Postwar Italy: The Legacy of Carla Lonzi, ed. Francesco Ventrella and Giovanna Zapperi (Bloomsbury Publishing, 2020).

Statement by Lina Mangiacapre from Nadia Pizzuti’s film Lina Mangiacapre: Artist of Feminism (2015).

Lina Mangiacapre, Cinema al femminile (Female cinema) (Mastrogiacomo Images 70, 1980), 2.

Giada Cipollone, “Nemesi Performativa: Scritture, Corpi e Immagini nella ricerca di Lina Mangicapre e delle Nemesiache” (Performative nemesis: Writings, bodies and images in the research of Lina Mangiacapre and Le Nemesiache), Mimesis Journal 10, no. 2 (2021): 41.

Lina Mangiacapre, interviewed by Nadia Nappo, Napoli Frontale, no. 3 (July 1998).

From an undated interview with Lina Mangiacapre.

Le Nemesiache, “Per una città a dimensione donna” (For a city of female dimensions), Quotidiano Donna 4, no. 2 (1981).

Giulia Damiani, “Feminist Ruptures With No Ends in Sight,” in Ceremony (Burial of An Undead World), ed. Anselm Franke et al. (Spector Books, 2002), 63.

Le Nemesiache, Manifesto metaspaziale (Le Nemesiache, 1973).

Gayatri Spivak, Death of a Discipline (Columbia University Press, 2003).

Lina Mangiacapre, Faust/Fausta (L’autore, 1990), 7.

Mangiacapre, Faust/Fausta, 9.

Mangiacapre, Cinema al femminile, 23.

Brenner Bhandar and Rafeef Ziadah, Revolutionary Feminisms (Verso Books, 2020), 4.

A. Putino and Lina Mangiacapre, “Il Mito della donna guerriera” (The myth of the female warrior), Manifesta, no. 0 (1988).

Mangiacapre, Cinema al femminile 2, 3.

Mangiacapre, Cinema al femminile 2, 1.

Lina Mangiacapre, “Per una Nuova Critica” (For a new criticism), in Non Solo Figura di Donna: Documenti della III e IV Rassegna del Cinema Femminista (Not only the figure of a woman: Documents of the III and IV Festival of Feminist Cinema) (Le Tre Ghinee/Le Nemesiache, 1978–79), 3.

Lee Maracle, Memory Serves: Oratories (NeWest Press, 2016), 31.

Silvia Federici, Re-enchanting the World: Feminism and the Politics of the Commons (PM Press, 2018), 78.

Federica Bueti, Critical Poetics of Feminist Refusals: Voicing Dissent Across Differences (Routledge, 2022), 111.

Lina Mangiacapre, “Lava, vulcani e sangue” (Lava, volcanos and blood), published posthumously in Il Paese delle donne (The country of women) (May 2004).

The research for this article has been supported by the Italian Council. Thanks fo Fausta Base, Silvana Campese (Medea), Conni Capobianco (Nausicaa), and Claudia Aglione (Elena) for speaking with me and sharing intergenerational memories of their participation in Le Nemesiache. Thanks to Andreas Petrossiants for generous and inspiring editorial support.