“Negative Anthropology” is a new series of essays, translations, and historical texts that center on disability, sexual dissidence, technics, race, and anti-colonialism. Although the materials in the series do not pursue a single shared argument, what joins them is a focus on the gap between forms of insurgent or resistant activity and the models of political representation and visibility that deny the force and legitimacy of such forms. Set within the profound shifts in technical, social, and ecological relations that mark the mutations of capital over the past two centuries, the series borrows its title from a term used by Günther Anders and Ulrich Sonnemann. In their accounts, “negative anthropology” names a reckoning with the human through what it is not: through the distance from the ideals historically posed for and imposed on it, and through the limits and failures of prospects for meaningful social transformation. Departing from that often philosophical work towards questions embedded in social and cultural history, the texts in this series consider the ways that even seemingly radical political frameworks—including those that rely on notions of of community and pride—have often been unable to account either for subjectivities that are not legible within their parameters or for the potent kinds of collectivity and action that start not from any presumed commonality but in the negative space around what gets understood as human in the first place.

—Evan Calder Williams, Contributing Editor

***

Piercing the virginal and magically seduced gaze of our Latin American ancestors, the famous Western conceptualization of sexuality—regrettably manipulated by the institution of the Church—arrived on a mystical ship. A new and deadly thinking was discharged across these lands, cemented through bloody insult and pillaging that continue unabated to this day, all with the aim of civilizing—according to chilling and ignorant criteria—the savage beasts that lived in this unknown paradise.1

It’s astonishing how this new form of thinking and its magical, mystical, religious, forcefully imposed representations spread. Today, shockingly, we still have it inscribed in our neuronal impulses and in each and every cell that makes up our mestizo body.

Thus, in a land where twisted Catholic laws didn’t exist, alien ideals were progressively imposed, through death and shameless aggression, on every region where this tempestuous scum propagated itself—destroying our rich and original Indigenous culture.

The conquistadors saw Indigenous men as wild, effeminate beings because of their adornments, and considered Indigenous women promiscuous because of their partial nudity.

Our ancestors were dressed up in clothing completely foreign to their own culture, their hair was cut to differentiate men from women, and they were forbidden from maintaining their many intersexual practices that, given their “aberrant” nature, perturbed the moralist Spanish mind.

In our vulnerable and half-sleeping Latin American socioculture today, we are still exposed to norms inherited from these violent conquistadors by way of a social, religious-moralist indictment that has mutated, for better or for worse, shaping these brutish forms of thought.

Do we exist because they discovered us?

It seems that our voice is only valued when the dominant ones encounter us and make us exist. It’s as if our history prior to colonization would’ve never happened … as if everything began with the discovery of America for these people who didn’t even know where they were, much less that we had existed—for many years—free of their disgusting miseries.

Where do we speak from today? From a land with history, or from a new territory discovered by others?

Today I speak geographically situated in the South, but it often seems that I am validated by speaking, as it were, from the North, as if following the dominator’s matrix of thought, which continues to guide us. I’m referring to how new understandings of Gender pile up at our borders and hem us in with new labels to advance and understand the exercises of existence and sexual difference.

So today, those from the North point us toward a new way of reading, so that we in the South can understand what already existed in our lands …

This Moche pot, circa 150–800 AD, depicts anal sex between two male cadaveric figures. Courtesy of Larco Museum, Lima, Peru.

Yes! Maricona culture has always existed within our borders, but it hadn’t previously been brought into focus in a way that unified its contents and saw them as fodder for a regimented or movement-based struggle—in the sense that the historical trajectory of new sexual identities and their sociocultural manifestations are often understood.

For example, as the writer Juan Pablo Sutherland narrates in his book Marica Nation:

In the seventies and eighties in Latin America, crimes against homosexuals continued to be a daily reality in Brazil, Argentina, and the rest of the region, … leaving a bloodstain that’s difficult to erase. In those years, … a large portion of South America was governed by military dictatorships, and many incipient initiatives arose in the face of brutal repression. In Argentina, the Homosexual Liberation Front was born, led by the poet and anthropologist Néstor Perlongher … In Chile, at the outset of the Popular Unity government, the first public homosexual demonstration was organized in the emblematic Plaza de Armas of Santiago, a protest that was characterized in the left-wing press as degrading and perverted.2

Today it seems like everything we’d done in the past is rising up and harmonizing with what Saint Foucault, in his day, described in the History of Sexuality and which, combined with years of marvelous feminism, finally arrived at what Saint Butler registered as “queer.”

I’m a new mestiza latina from the Southern Cone who never intended to be identified taxonomically as “queer” and who now, for gender theorists—according to new understandings, studies, and reflections that originate in the North—fits perfectly in that category, which proposes a botanical name for my extravagant species and defames it as “minority.”

When I discerned the tragicomedy of making a radical distinction of difference and refused to go along with the established gender binarism, I had thought that I was just a deformed, inadequate, and very effeminate human with a body biologically recognized as masculine. Logically a sin; excessively approximate to the abnormal, perverted, and deviant; socially cloistered as an immoral subject who didn’t deserve to enter the kingdom of heaven—I thought I had to beg for mercy, cry out for help to cure myself of this upsetting and frenetic pathology that made me withdraw from what was politically correct and established as “natural” in my geopolitical context.

I bravely resolved to confront others, and I nourished myself with shocking gluttonies that upended the social constructions typically populating our South American goings-on. I witnessed oppression and hostility firsthand, along with the discriminatory pleasure others experience by feeling upright and superior, meanwhile destroying personal integrity and trashing human dignity.

As a child I never identified with gender binarism. I felt I fit naturally into another, much more harmonious situation, and I played children’s games meant for both sides. I played soccer, and with Barbies; I kissed girls, and I kissed boys. Without a doubt, my childhood was sensational, pluralistic—and no child ever rebuked me in the least. On the contrary, everything emerged naturally from the free flow of life.

In the eighties, when I was five years old, they enrolled me against my will in an all-boys Catholic school. The situation seemed very bizarre to me. Every morning I prayed to the little Virgin so that she would change me into a princess. And when my little boy classmates played Star Wars, I was always Princess Leia. I always took the boys I liked by the hand, and the teacher would shout from a distance, “Boys don’t hold each other’s hands!” My mind, ignorant of heterosexual norms, never understood those shouts, which sought to restrict my natural, childish liberties.

After having many boyfriends in elementary and middle school, and rewarding boys who scored soccer goals with kisses on the mouth, one of the schoolteachers discovered my doll! Yes! It was my fabulous She-Ra doll—the twin sister of He-Man.

Mattel’s She-Ra versus Shadow Weaver doll set, 2019.

This teacher called my parents into school. She isolated me and sent me to the guidance counselor’s office.

After a profuse and traumatizing cry—because I did not understand the strange situation in which I found myself embroiled—I ended up enduring four years of psychological treatment to cure me of my homosexuality.

It is well known that homosexuality-as-pathology was eliminated from psychiatric textbooks only as recently as 1973, but since the dictatorship in my country began that same year … between the bombs and bloody, cannibalistic killings, surely that information never managed to get through to Chile. And so, my case was treated as a sickness, a mental disorder that was possible to cure through therapy. In this way, I could be made to successfully adapt to the patriarchal, cis-male chauvinist, heteronormative order.

As you can see, the results of my therapy were fabulous! I quickly learned to trick my psychologist, exploring my internal masculinity and performing like the most brutish and clever of men!

When the doctor signed my release, my body lit up like a bulb. It filled with freedom, and, in a burst of otherworldly healing, the advice that Gloria Trevi preaches today was then made flesh.

I let down my hair, I dressed like a queen, I wore heels, I put on makeup, and I was beautiful. I walked to the door—I felt you shout after me, but your chains could no longer hold me—and I looked into the night. It was no longer dark; it was sequined!

Now, according to our current and much-maligned reality, altered as it is by new orders of sexual classification and declassification, I should enroll myself in and become enamored of one of them so I can get along with this imposed neo-culture, which informs me of the fact that I represent a certain something that binds or unbinds me to the imposed binary gender system.

Following such reasoning while pluralistically oppressed and disorientated—amid so much new erudition that mixes and destabilizes what is coherent for some, and which for others is subject to constant change according to life’s sexual metamorphoses—and trying to identify with one of these neat little boxes … it only sends shivers down my spine.

Presently:

Am I a transvestite lesbian sodomite, fiery and citified?

Am I a sinful, effeminate bisexual with counter-sexual features suffering a delirium of transsexual transgression?

Am I an abnormal techno-woman with multi-sexual nymphomaniac carnal whims?

Am I a sexual monster normalized by the academy in the concrete jungle?

Am I a soul that God punished for becoming inverted, twisted, and ambiguous?

Am I a scintillatingly ornate, poor feminine homosexual inclined to capitalist sodomy?

Am I a transvestite penetrator of lubricated orifices ready for passionate episodes?

Am I a body in continuous identitarian flux in search of sexual pleasure?

Given the multiple extant forms of oppression and mechanisms of control, it is no longer clear if you are man, woman, gay, lesbian, transvestite, transgender, androgynous, or bisexual.

Today, social class, race, education, and geographic location all influence the concept of gender, although some who love heterosexual norms don’t want to open their little, conservative eyes and see the reality that’s right under their noses.

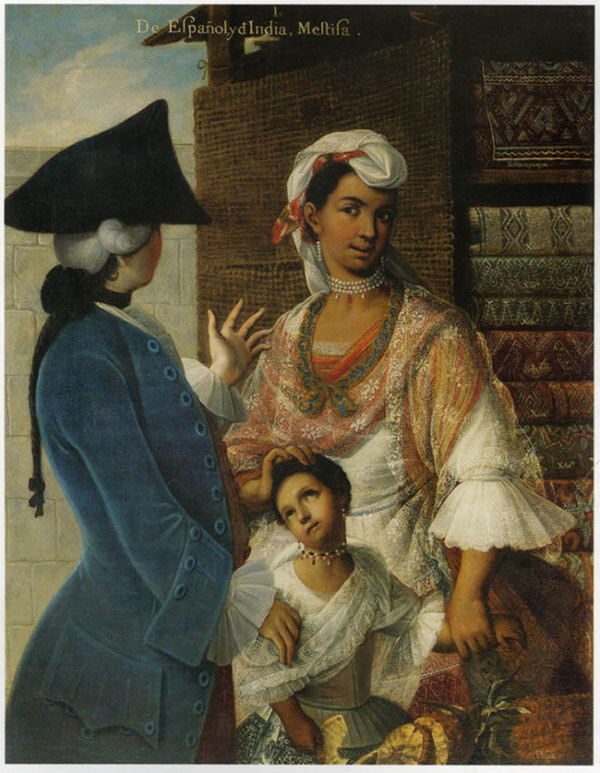

Miguel Cabrera, Casta Painting 1: From Spaniard and Indian, Mestiza, 1763. Museum of Mexican History, Monterrey, Mexico. License: CC BY-SA 4.0.

Why can’t some people understand this simple premise?

Sometimes I am weighed down by the dominant paradigm and feel trapped in a narrow model of two sexes.

What’s so great about being standardized and looking like a regiment?

Why is this idea politically suited to Latin America?

Just how upsetting is it to be indifferent to understanding which sexual box you fit into?

What is the problem with another individual being sexually ambiguous and difficult to read?

In what sense is it right and good to only understand which sexuality best accommodates your life by appearance and practice?

Why must you make it your business to know if I like to fuck excrement, or if I like old women to puke on me while I masturbate in mall urinals?

This is why it has been necessary to construct other terms that permit us to understand these very real aspects of our sexual lives from another perspective.

The expression “queer” descended on Latin America around the mid-nineties. Keep in mind the term had been coined in the North in the eighties.

Since we’re on the periphery of this North American debate, this information arrived belatedly and managed to be interpreted in a most singular fashion. As Sutherland describes it,

Some have run to inscribe their practices within the “queer” cathedral, as if to sanctify themselves in the most recent neo-vanguard of radical sexual politics. Others have attempted to translate the term from widely divergent lexical approaches: twisted, oblique, post-identitarian, weird, inverted, all of them performing linguistic gymnastics that attempt to evidence a normative malaise, a theoretical revelation, a Promethean flight from identity … They all play, on the political scene, at giving voice to a rejected and stigmatized experience.3

In a chapter of the book Por un feminismo sin mujeres (Toward a feminism without women), Felipe Rivas narrates:

“Teoría queer” is not the same as “queer theory” owing to the mode by which the Castilian enunciation sheds the political complexities that its role as critical thought might otherwise entail and which are contained in the very gesture enacted by its name. If in the United States, people like David Halperin denounce the rapid institutionalization of a “queer theory” that has been normalized by academic success, in Latin America and Spain this process seems to be unfolding at an accelerated rate due to the absence of tensions provoked by its reception in the local academic spaces, where no question or threat is perceived in its nomenclature, but rather a new, glamorous formulation of knowledge exported from the United States … The market in the peripheral countries of South America usually translates the name of its products into English as an advertising technique designed to increase the symbolic status of the commodity.4

We understand that in Latin America it is not the same thing to say “teoría maricona” as it is to say “teoría queer,” and therefore, this most snobbish of phonetic expressions helps offset suspicion on the part of academic gatekeepers, and avoids producing tensions and repercussions that might otherwise stigmatize this type of knowledge as illegitimate.

Can we enjoy “queer” shopping in our latitudes?5

Today, thank God, we have everything we need to take up the “queer” banner in the metropolis: a thousand products to transform ourselves into ambiguous beings, sexually difficult to read, and to go along performing identitarian transgression for life itself. Today it is possible to study this theory in universities and receive reliable information on the theme. Today it is commonplace to buy and sell books that translate this hopeful message and transport it to your nightstand. Today the possibilities offered by multi-sexual meetups, bars, discos, and so on exist and are at our disposal. Today there are bands with “queer” aesthetics whose music you can acquire and enjoy. Today there are stores with counter-sexual devices for our pluralistic, cyber-carnal stimulation. A world of fabulous opportunities to put our discourse into practice and achieve the aesthetic extravagance necessary to feel we are involved in and sanctified by all things “queer.”

The economic system easily collects new identities and imbues them with a pseudo-democratic aura. That’s what happened with the no-less-problematic concept already absorbed by a taxonomic and identitarian torrent, affirming “queer” subjects and “queer” politics. According to Slavoj Žižek:

We would have to support “queer” political action to the degree that it analogizes its struggle to the point that … it mines the potential of capitalism itself. The problem, however, is that with its continuous transformation toward a tolerant, “post-political,” multicultural regime, the capitalist system is capable of neutralizing “queer” causes and integrating them as “lifestyles.”6

What is the future of this theory that runs the risk of being swallowed up and bought at a cheap price by the capitalist system?

We can note that in the context of academic research related to gender and sexual identity, this “queer” theory that seduces and enchants us has the virtue of offering a novelty that implies an etymological crossing of boundaries without referring to anything in particular, which leaves the question of its detonations open to argument and revision.

Thanks to that ephemeral nature, “queer” identity could apply to any person who ever felt out of place in the face of restrictions imposed by heterosexuality and established gender roles.

It proposes that nothing in our identities is fixed—that gender, like all other aspects of identity, is performed, and that people, therefore, can change.

Its contribution is the possibility of subverting and displacing those notions of gender that have been naturalized and reified in support of cis-masculine hegemony and heterosexual power. It challenges the idea that certain gender expressions are original or true, while others are secondary and false.

Saint Butler proposes the denaturalization of “hetero-reality,” in which normative sexual practice transforms into a regime of power that plays a role in every social relation: the economy, legal logic, public discourse, daily life, etc.

The “queer” struggle doesn’t aim only for tolerance and equal status, but to challenge these institutions and ways of understanding the world.

“Queer” theory tries to understand different modes of sexual desire and how culture defines them.

Let us understand that we are part of a Latin America where an obvious pluri-sexual and multi-sexual culture exists that many don’t want to see or understand, where sex change and implant operations are performed every day, where free human beings, enjoying their experience between various genders and enjoying the natural bounty of sexuality, exist and coexist with people who are undergoing hormone treatments to modify their bodies and become more like who they aspire and feel themselves to be. In parallel, unfortunately, others are full of religious guilt and hide, condemning themselves to dark underworlds, thinking that they are immoral monsters persecuted by that part of society that points a finger at them, seeks to make them feel inferior, and does not recognize their rights.

Finally, we are part of a jungle where an equilibrium between good and evil prevails, a context in which we should elevate our level of consciousness and seek to understand the human who sought to move away from knowledge and base their life instead on fear, deciding to use others and disrespect different kinds of lives.

It would be in our collective best interest to abandon old definitions. In the same way that you discovered the truth about Santa Claus and the Easter Bunny, you now discover that there’s been a frame-up—a made-up history, an idealized version of all those things you never wanted to reflect on before and which you adored as if they were gods.

I’m not standing here, in the South of the world, to say who is right. I only wish to throw into disarray prevailing illusions and those idealizations that mystify our problems, and to pop the balloons in which you’ve come to believe. There’s nothing left for me but to suggest that you think big!

Can I dream that “the queer” will continue its legacy of resistance and liberty of expression and not be transformed into a fashion or norm?

I hope the utopian idea of my disturbed mind becomes a reality and “queerness” is transmogrified into a constant deconstruction and loving creation, where we can all get along with wisdom and pleasure.

After my nighttime masturbation I will continue dreaming and imploring the universe for education in Latin America to change, and that from the very beginning of human subject-formation we will utilize these kinds of knowledge so that our children, free of generic, imposed impurities, might form themselves free from social stigmas, and that this idea of learning in an environment of gender neutrality—eradicating stereotypes and inequality—spreads as forcefully as the reigning mystical ideologies once did, to reach every corner of the world.

He dicho! Caso cerrado.

This text was originally presented as a lecture at the 3rd Queer Art Fair of Mendoza, hosted by the Center of Information and Communication of the National University of Cuyo in Argentina, November 16, 2012. Thanks to Aberrosexuales, Universidad de Cuyo, Lelya Troncoso, Cristeva Cabello, Jorge Díaz, Javiera Ruiz, Esteban Prieto, and my progenitors Rosita and Orlando.

Juan Pablo Sutherland, Nación Marica, prácticas culturales y crítica activista (Marica nation: Cultural practice and activist critique) (Ripio Ediciones, 2009), 14.

Sutherland, Nación Marica, 15.

Felipe Rivas, Por un feminismo sin mujeres, fragmentos del segundo circuito de Disidencia Sexual (Toward a feminism without women: Fragments from the second circuit of sexual dissidence) (Territorios Sexuales Ediciones, 2011), 68.

The English word “shopping” appears here in the original Spanish. The author’s wordplay pokes fun at colloquial use of “shopping” (instead of a Spanish phrase like ir de compras) in Latin American Spanish. —Ed.

Slavoj Žižek, En defensa de la intolerancia (In defense of intolerance) (Ediciones Sequitur, 2005), 69. Translated here from the Spanish.

Category

This essay was first published in Spanish in Revista Punto Género, no. 4 (2014). It is republished courtesy of Silvia Lamadrid and Revista Punto Género.

Translated by Casey Butcher with editorial assistance from Santiago Silva Daza and Judah Rubin.

A prior version of the English translation was published in a limited-edition publication (designed by Julien Hébert) for the exhibition Living in Foul, curated by Julia Eilers Smith at the Hessel Museum of Art in 2019.