Continued from “Capitalism and Schismogenesis, Part 1”

Unexpected Subjects, Making History Otherwise

The Black radical tradition is marked by a ricocheting debate on historical materialism, on the dialectical negation of the negation, and on Alexandre Kojève’s Marxist interpretations of Hegel’s parable of master and slave (or, in a more literal translation from the German, lord and bondsman) as the principle of class struggle and of history itself. If C. L. R. James largely tended to view anti-colonial struggle through the prism of class struggle, Sylvia Wynter has noted that his literary work went a step further: James’s alter ego had the telling name of “Matthew Bondsman” and needed “to come to terms with the fact that he had become ‘refuse.’”1 Francophone Caribbean thinkers such as Aimé Césaire and Frantz Fanon effected a more decisive break with Hegel. In Fanon’s pithy gloss, the real-world master of the plantation “laughs at the consciousness of the slave” and wants relentless toil from his slaves, rather than something as useless and unproductive as “recognition.”2 As Donna V. Jones summarizes Fanon’s critique, “The Hegelian dialectic simply does not seem to fit the experience of African slaves in the New World: it is nonsensical that chained and whipped slaves could see in work a vehicle for self-realization.”3 Emancipation thus needs to take the form of emancipation from work, not through work.

In the context of second-wave feminism, Carla Lonzi likewise attacked Hegel’s master-slave dialectic, again understood in Kojèvian terms as the dialectical principle of all history:

Had Hegel recognized the human origin of woman’s oppression, as he did in the case of the slave’s, he would have had to apply the master-slave dialectic in her case as well. But in doing so he would have encountered a serious obstacle. For, while the revolutionary method can capture the movement of the social dynamics, it is clear that woman’s liberation could never be included in the same historical schemes. On the level of the woman-man relationship, there is no solution which eliminates the other; thus the goal of seizing power is emptied of meaning.4

This has radical consequences: “We recognize within ourselves the capacity for effecting a complete transformation of life. Not being trapped within the master-slave dialectic, we become conscious of ourselves; we are the Unexpected Subject.”5 To a significant extent, the history of social movements in the last half-century has been shaped by Unexpected Subjects asserting their agency. The fallout has been significant, from the co-optation of new subjectivities as upwardly mobile identities to the proliferation of paleo-leftist calls for universalism—in a reified retro register that effectively turns their universalism into a covert form of identitarian particularism.

This development raises fundamental questions about History as an ongoing dialectical process operating through the negation of the negation. The question is not so much if the historical dialectic has reached, or can reach, its culmination in the End of History, but what kind(s) of history are being pursued—possibly simultaneously, if asynchronously. In the Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844, Marx argued that socialism properly understood will be the abrogation of this historical process. If capitalism as based on private property negated the precapitalist stage, communism as a negation of capitalism will still bear the marks of the capitalist form of ownership and production (as was the case in the “actually existing socialist” countries of the twentieth century). Communism in that sense cannot be the goal or end of history; it is a mediation still marked by the negation of the negation, and will be followed by a (post-)historical period of “positive self-consciousness” and “positive reality.”6 It is here that early Marx resonates both with Césaire and with Deleuze—two thinkers of the line of flight, with Deleuze insisting on the need for “undialectical negations” that amount to “positive difference.”7 Deleuze emphasizes the reality of such positive difference: it is not a matter of waiting for the end of history, but of opening up lines of flight while instigating divergences and desertions right here, right now, on the molecular level. This is where Deleuze meets Negri and where Deleuzianism blends into autonomia.

At a historical moment marked by the memeification and trollification of political theory, some lay into the autonomist politics of immanence to hawk some kind of “properly political” Leninist party politics, albeit one reduced to a theoretical brand. The point is not to minimize the limitations and contradictions of autonomism, nor to deny the relevance of the party form as part of an overall assemblage of imperfect organizational formations, of vertical and horizontal structures. However, one fundamental clarification seems to be necessary: not unlike that of immanent critique in the tradition of the Frankfurt School, immanent political practice aims to work with and against the contradictions of labor and life so as to exacerbate them and find moments of externality.8

Creating different social relations under the reign of the value-form and the nation-state is obviously a tall order—but then, it is not necessarily always clear where this “reign” ends. Can the limits of capitalism be defined in any meaningful manner? Nancy Fraser has noted that “capitalism is something larger than an economy” in that it also remakes and shapes “the ‘non-economic’ background conditions that enabled such an ‘economic system’ to exist.”9 Capitalism, then, is expansive and expansionist. Another feminist critique of capitalism points in a different direction from Fraser’s diagnosis: J. K. Gibson-Graham’s “iceberg model” shows a visible tip with “wage labour, production for markets, capitalist business,” while bubbling below the surface is the much bigger mass of nonmarket exchange and cooperation.10 Here, contrary to Fraser, the economy is something larger than capitalism, if we use the term “economy” in a more encompassing sense to include all forms of social (re)production.

Together, these positions can be used for a dialectical—rather than binary—account of the potentiality and limits of anti-capitalist schismogenesis. Yes, capitalism involves an imperialist conquest and a transformation of social relations by the value-form, but the process is unfinished and open-ended. Capitalist productive relations propel an ongoing process of primitive accumulation that is open-ended—economically, if not ecologically, since the earth is a closed system.11

As long as it lasts, there will always be new economic frontiers to be conquered. Global warming itself has been transmuted into a business opportunity. However, the antagonisms and leftovers that are generated in the process cannot be fully contained by the logic of capitalist development; this is a planet of war zones and toxic wastelands, of surplus populations and mass migrations. But the dominant media imaginary of collapse and barbarism needs to be questioned itself. The uneven exposure to slow violence notwithstanding, nobody can truly desert from climate collapse, but there are different ways of living in the catastrophe—of “winging it through the apocalypse.”12

Inspired in part by Deleuzian discourse, autonomist desertions can be seen as attempts to enact schismogenesis otherwise, to produce constitutive divergences without following any sequence of negations decreed by the historical dialectic: “We dreamed of waking up every morning in a place where secession from the system was a permanent process.”13 What is at stake here is schismogenesis beyond the counter-mimetic mechanisms of diversifying and indeed clashing lifestyles and identities under capitalism, of culture wars and ideological divergences. To what extent, though, can one speak of an emerging schismogenetic divergence between societies, along the lines of Graeber and Wengrow’s “indigenous critique”?14 With Gibson-Graham, it should be noted that residual forms of noncapitalist cooperation are everywhere in this world. Much contemporary activism revolves around attempts to transmute residual commons into a reemergent force, and certain infrastructures of contemporary art have provided a degree of support and publicness for schismogenetic articulations and divergent forms of life.

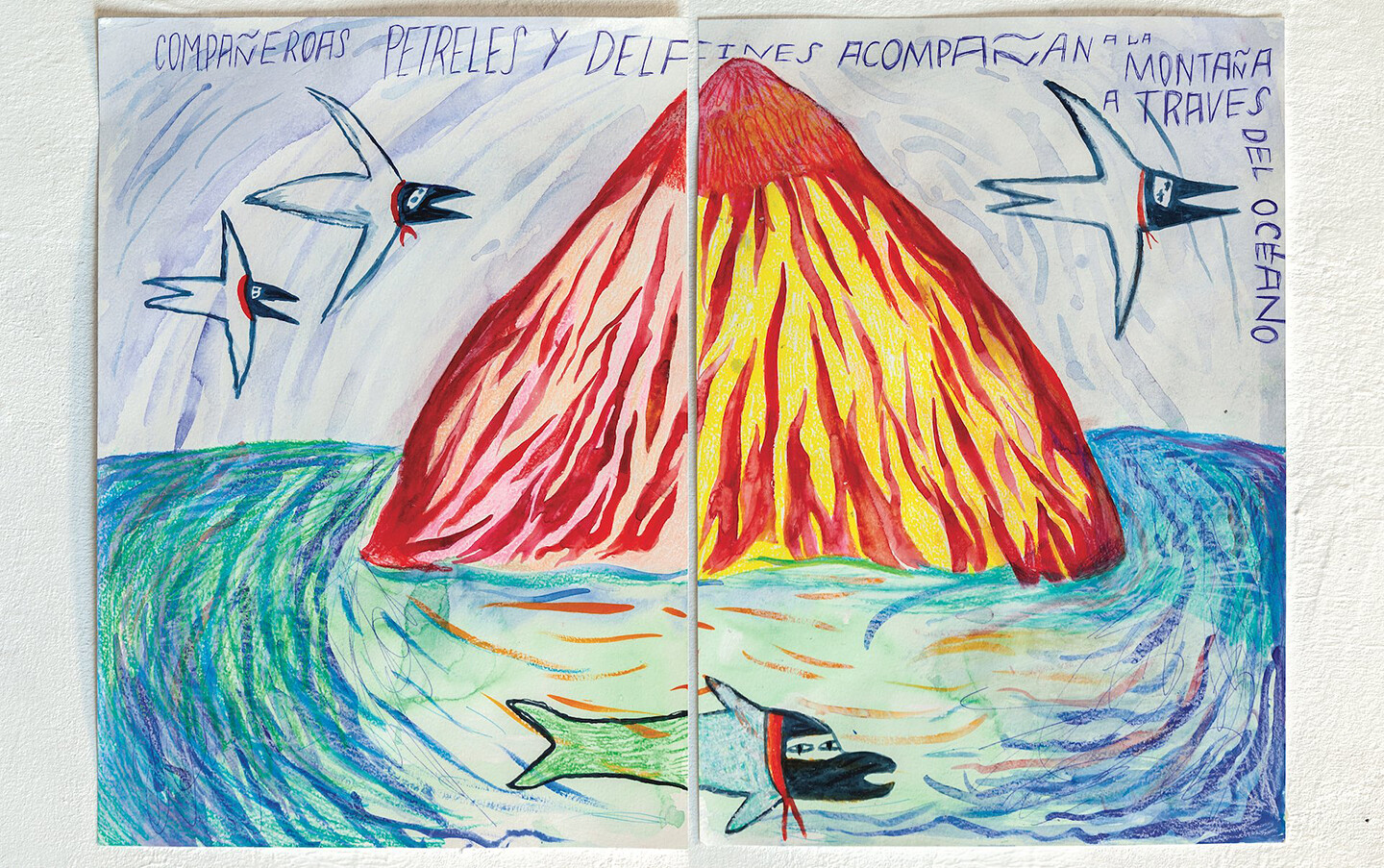

Nikolay Oleynikov (Chto Delat), Untitled (La Montaña…); Comrades Petrels and Dolphins Accompany the Mountain Across the Ocean, 2021. Dyptich, mixed media, 29.7 x 42 cm each. Courtesy of the artist.

In a 2008 manifesto, the Russian collective Chto Delat declared:

We believe that capitalism is not a totality, that the popular thesis that “there is nothing outside capital” is false. The task of the intellectual and the artist is to engage in a thoroughgoing unmasking of the myth that there are no alternatives to the global capitalist system. We insist on the obvious: a world without the dominion of profit and exploitation can not only be created but always already exists in the micropolitics and micro-economies of human relationships and creative labor.15

In a comment from 2010 on this statement, then Chto Delat member David Riff discussed the point against totalization in terms of residual and emergent elements, and of a multiplicity of capitalisms:

It is as if we see many different capitalisms all competing with one another, and miraculously working together to raise the productivity of the system as whole. At the same time, there are nooks and crannies where atavisms thrive, places that global capital leaves aside, only to capture them later on, or zones that it develops, fixes, and abandons. We need to work in these “interstices” once capital flees to re-imagine what Marx meant when he says that every old society is pregnant with a new one.16

Even discounting the peculiar pang that comes from rereading such sentences at a moment when the Putin regime clamps down on internal dissent while bombing Ukrainian cities, the seemingly inexorable transformation of visual art into a freeport-bound asset class can make this thinking seem all too wishful. “Critical” artists and organizations happily take handouts from the upper reaches of finance capital, German collectors mit Nazihintergrund, or the sheikha of Sharjah.17 Curators tirelessly pushing decolonial or feminist “content” behave like neoliberal war machines, and woke-washing abounds. Embodied contradictions breed behavioral pathologies: discourse teems with terms like “collaboration” and “care,” but those caring collaborators act like neoliberal self-entrepreneurs working on their brand. The most plutocratic institutions tweet black squares in support of Black Lives Matter, and in an art magazine’s “Power Top 100” of the art world, the 2021 number one spot was fashionably awarded to a nonhuman entity, a standard for NFTs, while number thirty-five is for a Black curator who works for one of the most powerful transnational gallery behemoths, which supposedly amounts to “changing the system from within.”18 The ideal product of contemporary cultural capitalism is woke crypto art. If contemporary art has been a force of emergence, it has been the emergence of the now-dominant—though increasingly crisis-ridden and fracturing—order.

Could dominant organizational structures themselves be sites of emergence? This is the contention of the strand of leftist theory that takes cues from early-twentieth-century debates on social planning: just as Lenin viewed the German main system as an incubator of social planning, and Otto Neurath considered the partial socialization of production in the war economy of WWI as a first step towards a fully socialized and planned economy, current theorists propose Amazon or Walmart as models for socialized planning in the era of big data. I have argued elsewhere that the “socialist calculation debate 2.0” urgently needs to take on board left-radical, councilist positions that foreground workers’ self-organization.19 If classic council communism remained largely fixated on white male industrial workers, today’s councils need to take on board machinic labor and the human jobs that inform it (from programmers to click-workers), reproductive labor, cultural work, and surplus labor—in the Global South as well as in the Former West. For Documenta 15, ruangrupa used the term “lumbung,” a name for Indigenous common rice barns in Indonesia, to refer to its collectivized funds; one participant mused that viewing “lumbungs as soviets” (i.e., councils) suggested “the possibility to have an autonomous federation of workers that self-determine their labour, activities, and self-organize for the common good.”20

If the scenarios and models of the historical Dutch and German councilists were predicated on revolution and full socialization, today’s networked groupings and their assemblies are precarious prefigurations. But just what is it that is being prefigured by such emergent forms of life? These are immanent desertions that seek to create zones of alterity by detourning imperial infrastructures. They constitute what Jameson would call “a dialectic between the non-dialectizable and the dialectizable.”21 As some fairly unexpected subjects are beginning to actualize potential forms of life and divergent social forms under precarious conditions, they are riven by external attacks and internal conflicts. How to turn the sum of desertions into an “antisystemic worldmaking project”—to use Adom Getachew’s term for postwar decolonization—with repercussions beyond a few pockets here and there?22

Indigenist Divergences

Having raised these questions, I will end—for now—not with grand pronouncements but with some notes on one particular set of divergent practices: activist and artistic practices that can be termed Indigenist. This is not the realm of grand designs and retro-accelerationist schemes, but of a tenacious temporality. Beyond the merely residual, Indigenous “survivance”—to use Gerald Vizenor’s term—has led to an Indigenous revival that inspires other forms of activism and cultural production.23 In James Clifford’s words, “Indigenous people have emerged from history’s blind spot,” having refused to follow the script that pre-ordained their disappearance.24 In his book on Indigenous renaissance, Clifford insists that “global capital and the state are active forces but not determining structures,” which forms a salutary counterpoint to totalizing conceptions of “the system.”25 Perhaps this needs to be thought of in terms of degrees: such forces can act as determining structures in some parts of the world, for some people. Real abstraction is an operational force with real agency but an uneven reach.26

Again, the question is if and how divergent forms of life are possible in and against the structures that have globalized the world. Clifford references Raymond Williams’s account of the “‘dominant, residual, and emergent’ elements in any conjuncture” as factors that

do not necessarily form a coherent narrative in which the residual indexes the past, and the emergent the future … Yet many forms of religious practice today—the global reach of Pentecostalism comes to mind—can be considered both residual and emergent. The same can be said of indigenous social and cultural movements that reach “backward” in order to move “ahead.”27

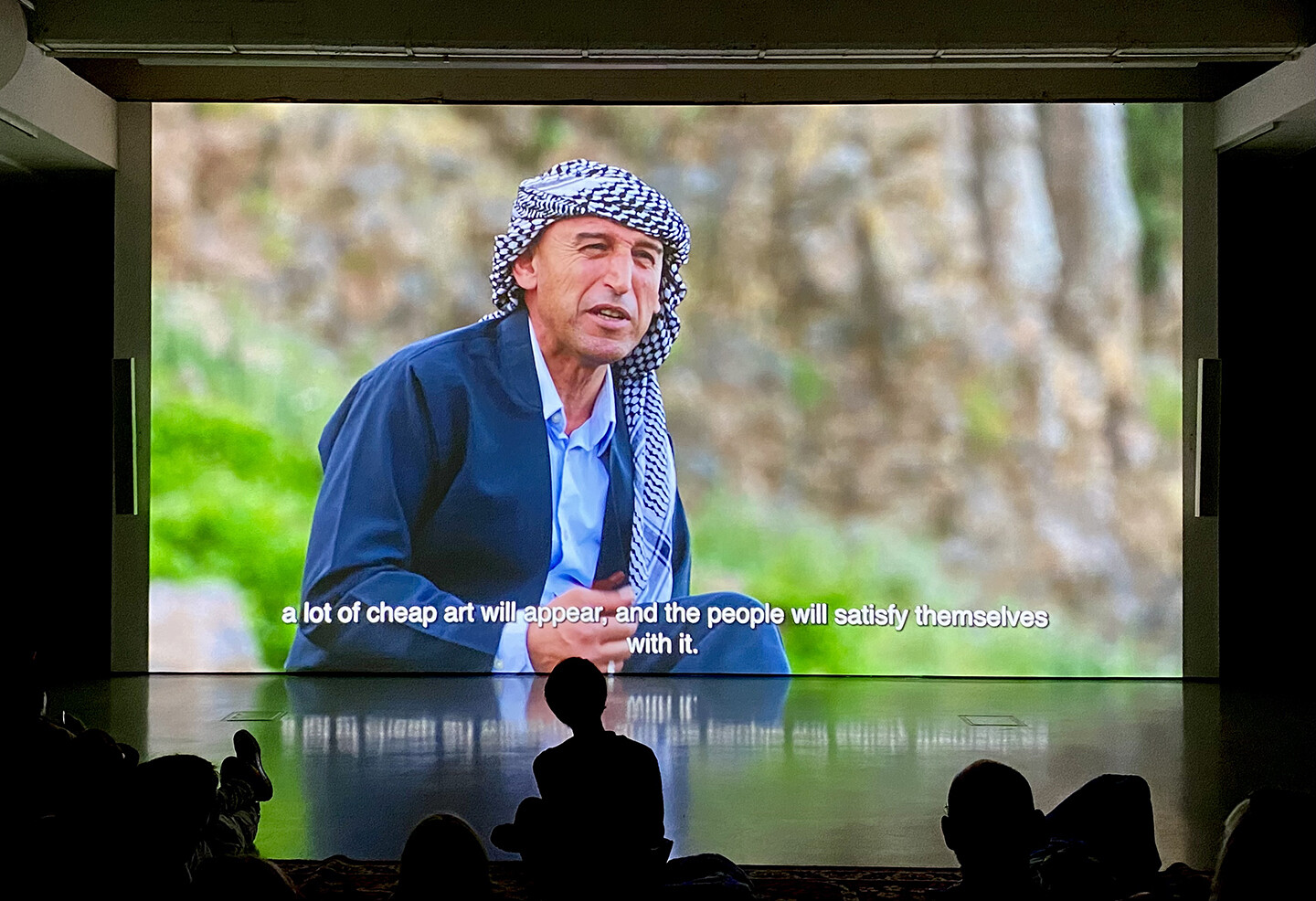

The Rojava Film Commune, Documenta 15, 2022.

From Chiapas to Standing Rock, contemporary Indigenism is indeed not so easily mapped onto Williams’s sequence. It has a significant presence in contemporary art, from the work of the Karrabing Film Collective to the presentation of masks by Kwakwaka’wakw artist Beau Dick at Documenta 14—and indeed to ruangrupa’s Documenta 15, which hosted Aboriginal artist Richard Bell’s Embassy as well as the Rojava Film Commune’s The Lonely Trees (2017), a mesmerizing montage of elderly people singing traditional Kurdish songs. In T. J. Demos’s words, emancipatory chronopolitics is simultaneously retrospective and proleptic.28 This means that divergence can no longer be immediately mapped onto a historical axis in which a cascade of determinate negations makes the dominant residual and the emergent dominant. As a set of chronopolitical practices, Indigenist activism and art requires a rethinking of futurity.

To return briefly to Chto Delat: their early work—roughly the ten years starting from the collective’s founding in 2003—was marked by a serious engagement with Marxism, with early Soviet constructivism, and with Brecht, on the basis of an autonomist conception of cultural activism.29 An early interest in “autonomous zones” later fed into an engagement with Zapatismo and the EZLN. They write: “It is clear that the experience of Zapatismo poses a serious question about the possibility of political organization and autonomy, an experience which has in many ways been actualized by the Kurds’ armed struggle as well.”30 Translations of Zapatista writings and collective work in Chiapas led to subsequent pedagogic projects, publications, exhibitions, and collective filmmaking; Godard’s injunction to “make films politically” became “making films zapatistically.” Here, radical practice is indigenized via movements—in Chiapas and Rojava—that are themselves complex, syncretistic assemblages of Indigenous survivance and elements from modern political theory and tactics.

Third-worldist and Indigenist elements were already strong in the post-’68 left in Europe, with groups naming themselves after the Tupemaros, using names such as “Indiani Metropolitani” (in Italy) or “Stadtindianer” (Germany), or adopting the tactics of urban guerrillas. Meanwhile, the Tricontinental movement organized by OSPAAAL in Cuba pushed for decolonization both in terms of the (armed) liberation of territories and of cultural sovereignty. Even while much of the art world is in thrall to a discourse on decolonization that revolves around representation, the epistemology of identity, and cosmology, the anti-systemic contestations of Chiapas and Rojava resonate on the pervasive margins. In 2021, a Zapatista delegation visited Europe, where its members were hosted in art spaces and by various activist communities with a particular presence and resonance in the “territorial bases of counter-power” that exist in various cities and in the countryside.31 Walls in the autonomist stronghold of Friedrichshain in Berlin sported flyers calling for the defense of embattled squats as well as posters welcoming the Zapatista delegation. While it is questionable to what extent the networks of interlinked autonomist squats, communes, and “zones à defendre” in the Global North represent systemic (or anti-systemic) alternatives, the contacts and alliances with Indigenous and other anti-imperialist contestations in the Global South clearly need to be seen as part of the equation. But is the situation of Chiapas—or Rojava—not after all that of an island in a capitalist sea? This problem is not new, nor are the challenges of networking and federating initiatives to create an anti-capitalist archipelago, a project that would require intercommunal organizing.32

The Indigenous resurgence is a striking case of complementary and asymmetrical schismogenesis, with Indigenous activists and artists drawing strength from defining their values in opposition to capitalist extractivism. Contemporary Indigenism posits that another world is indeed possible and that the future is Indigenous—chiming with Graeber and Wengrow’s sense of the protean possibilities and plasticity of the social. If many in the West today have the sense that the world is coming to an end, it is very much their world that is ending; other worlds were invaded and ripped apart long ago, yet the peoples in question refused to disappear—or, as with the Creole populations of the Caribbean, they became an unprecedented people spanning several aboriginal pasts, the long present of (neo)colonialism, and uncertain futures. Meanwhile the extractivist machine keeps accelerating—even amidst the symptoms of planetary collapse. The million-dollar question—to use an inappropriate metaphor—is to what extent contemporary forms of asymmetrical schismogenesis can maintain or produce forms of life in opposition to financialized and racialized capitalism. In a classic understanding of schismogenesis, this oppositional and relational element is primary; the schismogenetic process proceeds through negation and differentiation. However, with Stengers we can also posit a constitutive divergence as primary; the relational and oppositional aspect would be a secondary consequence, as no position in today’s globalized world can help but enter into relation.

Even if we choose to side with desertions and divergences from history, with attempts to create undialectical negations and positive differences, there is always a relation. The historical dialectic is not abrogated, but is troubled by the unexpected and the potential—generating a second-order dialectic of the dialectizable and the non-dialectizable. Familiar scripts must be rethought. Whether it is historical slaves or their contemporary descendants, or Indigenous activists and cultural producers, or divergent subjectivities opening “new perceptions and practices of the material world,” all of these positions and practices assert that another history must be possible in order for another world to be.

Sylvia Wynter, “In Quest of Matthew Bondsman: Some Cultural Notes on the Jamesian Journey,” in Urgent Tasks, no. 12 (Summer 1981), emphasis in original →.

Frantz Fanon, Black Skin, White Masks (1952), trans. Charles Lam Markmann (Pluto Press, 1986), 220.

Donna V. Jones, The Racial Discourses of Life Philosophy: Négritude, Vitalism, and Modernity (Columbia University Press, 2010), 167. See also, more broadly, 163–70 of Jones’s important study.

Carla Lonzi, “Let’s Spit on Hegel” (1970), trans. Veronica Newman, 2010 →. On Lonzi, see also Feminism and Art in Postwar Italy: The Legacy of Carla Lonzi, ed. Franceso Ventrella and Giovanna Zapperi (Bloomsbury, 2020).

Lonzi, “Let’s Spit on Hegel,” 18. See also Janet Sarbanes, “On Difference, Self-Valorization, and the Unexpected Subject,” chap. 5 in Letters on the Autonomy Project (Punctum Books, 2022).

“Socialism is man’s positive self-consciousness, no longer mediated through the abolition of religion, just as real life is man’s positive reality, no longer mediated through the abolition of private property, through communism. Communism is the position as the negation of the negation, and is hence the actual phase necessary for the next stage of historical development in the process of human emancipation and rehabilitation. Communism is the necessary form and the dynamic principle of the immediate future, but communism as such is not the goal of human development, the form of human society.” It should be noted that Marx’s use of the terms “socialism” and “communism” here differs significantly from later usage. Karl Marx, “Private Property and Communism,” in Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844, emphasis in original →.

On Marx’s discussion in the 1844 Manuscripts of communism as a mediation to be superseded, see also Chris Arthur, “Hegel, Feuerbach, Marx and Negativity,” in Radical Philosophy no. 35 (Autumn 1983). On Deleuze, see Michael Hardt, Gilles Deleuze: An Apprenticeship in Philosophy (University of Minnesota Press, 1993), xii, 33, 62. On Césaire, see Jones (drawing on Hardt), Racial Discourses of Life Philosophy, 168–70.

My phrasing here invokes Howard Caygill’s discussion of Walter Benjamin’s immanent dialectical criticism; Caygill, Walter Benjamin: The Colour of Experience (Routledge, 1998), 62–63. For immanent critique from a Frankfurt School perspective, see also Rahel Jaeggi, Critique of Forms of Life, trans. Ciaran Cronin (Harvard University Press, 2018).

Nancy Fraser, “Behind Marx’s Hidden Abode: For an Expanded Conception of Capitalism,” in New Left Review, no. 86 (March–April 2014): 66. See also Fraser’s recent elaboration on this article in Cannibal Capitalism: How Our System Is Devouring Capitalism, Democracy, Care, and the Planet—and What We Can Do about It (Verso, 2022).

The diagram was originally devised by Community Economies Collective in 2001 and drawn by Ken Byrne. See J. K. Gibson-Graham, A Postcapitalist Politics (University of Minnesota Press, 2006), 70.

The point that so-called primitive accumulation (unsprüngliche Akkumulation) presupposes the development of capitalist productive relations, and thus does not “precede” capitalism, is made by Pepijn Brandon in his lecture “Elements of Original Accumulation: Dispossession, War, and Slavery in the History of Capitalism,” Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, May 23, 2023 →.

An expression used by Jota Mombaça during a gathering in the context of Jeanne van Heeswijk’s exhibition “It’s OK … commoning uncertainties,” Oude Kerk, Amsterdam, July 7, 2023 (quoted from memory).

Isabelle Fremeaux and Jay Jordan, We Are “Nature” Defending Itself: Entangling Art, Activism and Autonomous Zones (Pluto Press, 2021), 43.

David Graeber and David Wengrow, The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity (Allen Lane, 2021), 27–77.

Chto Delat, “A Declaration on Knowledge, Politics, and Art” (2008), with comments by Dmitry Vilensky and David Riff (2010), in the newspaper Chto Delat? What Is to Be Done? in Dialogue (reader), 2010, 2 →.

Comment by David Riff in Chto Delat, “A Declaration on Knowledge, Politics, and Art,” 2.

The German phrase “Menschen mit Nazihintergrund” was proposed as an ironic variation on the phrase “mit Migrationshintergrund”; see for instance Michael Rothberg, “‘People with a Nazi Background’: Race, Memory, and Responsibility,” in Los Angeles Review of Books, May 20, 2021 →. The term has been applied to prominent art collector Julia Stoschek.

See →.

Sven Lütticken, “Plan and Council: Genealogies of Calculation, Organization, and Transvaluation,” Grey Room, no. 91 (Spring 2023).

Jazael Olguín Zapata, “Lumbungs of the Worlds: An Ongoing Making,” in documentamtam, no. 4 (May 2022) →.

Fredric Jameson, Valences of the Dialectic (Verso, 2009), 26.

Adom Getachew, Worldmaking after Empire: The Rise and Fall of Self-Determination (Princeton University Press, 2019); Getachew characterizes the International Workingmen’s Association as having constituted the first such project (3).

Gerald Vizenor, Manifest Manners: Narratives of Postindian Survivance (University of Nebraska Press, 1999).

James Clifford, Returns: Becoming Indigenous in the Twenty-First Century (Harvard University Press, 2013), 13.

Clifford, Returns, 37.

See my Objections: Forms of Abstraction, vol. 1 (Sternberg Press, 2022).

Clifford, Returns, 28.

T. J. Demos, Radical Futurisms: Ecologies of Collapse, Chronopolitics, and Justice-to-Come (Sternberg Press, 2023), 14.

The second issue of the Chto Delat newspaper was titled “Autonomy Zones” (2003).

Dmitry Vilensky (Chto Delat), “Unlearning in Order to Learn,” in When the Roots Start Moving, First Mouvement: To Navigate Backward / Resonating with Zapatismo, ed. Alessandra Pomarico and Nikolay Oleynikov (Archive Books, 2001), 65.

See interview with Ramor Ryan, “Zapatismo, Solidarity and Self-Governance: A Conversation,” in ROAR, March 23, 2022 →.

On historical debates among anarchists in the wake of the Paris Commune, and on creating federations of cooperatives so as to prevent them from becoming isolated islands, see Kristin Ross, Communal Luxury: The Political Imaginary of the Paris Commune (Verso, 2015), 117–42. Léon Lambert argues that the Commune already installed a form of “archipelagic sovereignty” linking up autonomous islands, and potentially stretching beyond Paris to include “rural islands.” See Léopold Lambert, “The Paris Commune and the World: Introduction,” The Funambulist, no. 34 (March–April 2021): 13.

Category

Subject

This essay is based on a chapter of my forthcoming book States of Divergence. For various reasons, including feedback on early drafts or for productive comments at conferences and symposia, I would like to thank James Clifford, Stewart Martin, and Stevphen Shukaitis.