Today I have become a member of that same generation I despised when I was a student. This was a slow and insidious process that I only perceived gradually and marginally. I started thinking about retirement when a student who was a fan of hip-hop asked me what music I liked. I answered that I favored classical music. After a long silence he looked at me and said, “Oh, you mean The Beatles?”

If you believe in progress, the old and aged are always to blame for causing the persistent problems of the present, and the young, who supposedly come later, are the solution. This is all very tidy until you wake up one day to find yourself old—and observe that the young who blame you are also the young who are causing the problems of the future, just as you had in your own youth. In this issue, Luis Camnitzer offers advice to the aging—which, to be clear, means all of us—through an anecdotal contribution to the field of intergenerational dialogic studies. He discusses attempts at nonauthoritarian child rearing; his experience, while a student activist, of explaining an art historian’s own obsolescence to his face; and recent moments when he’s realized that his generation has become ineffective at communicating with the young. In other words, Camnitzer fears that his has become the generation suffering from “asshole syndrome”—a diagnosis he and his fellow students used to dole out. Age and power together form a complex configuration, which make empathy and self-assessment all the more important when communicating across generational lines.

I would say that contemporary civilization is a civilization in which nothingness has disappeared. Kabakov’s treatment of garbage still retains the intuition of nothingness. He assumes that it is possible to disappear into nothingness, and he often describes it—for example, as a departure into outer space from one’s room.

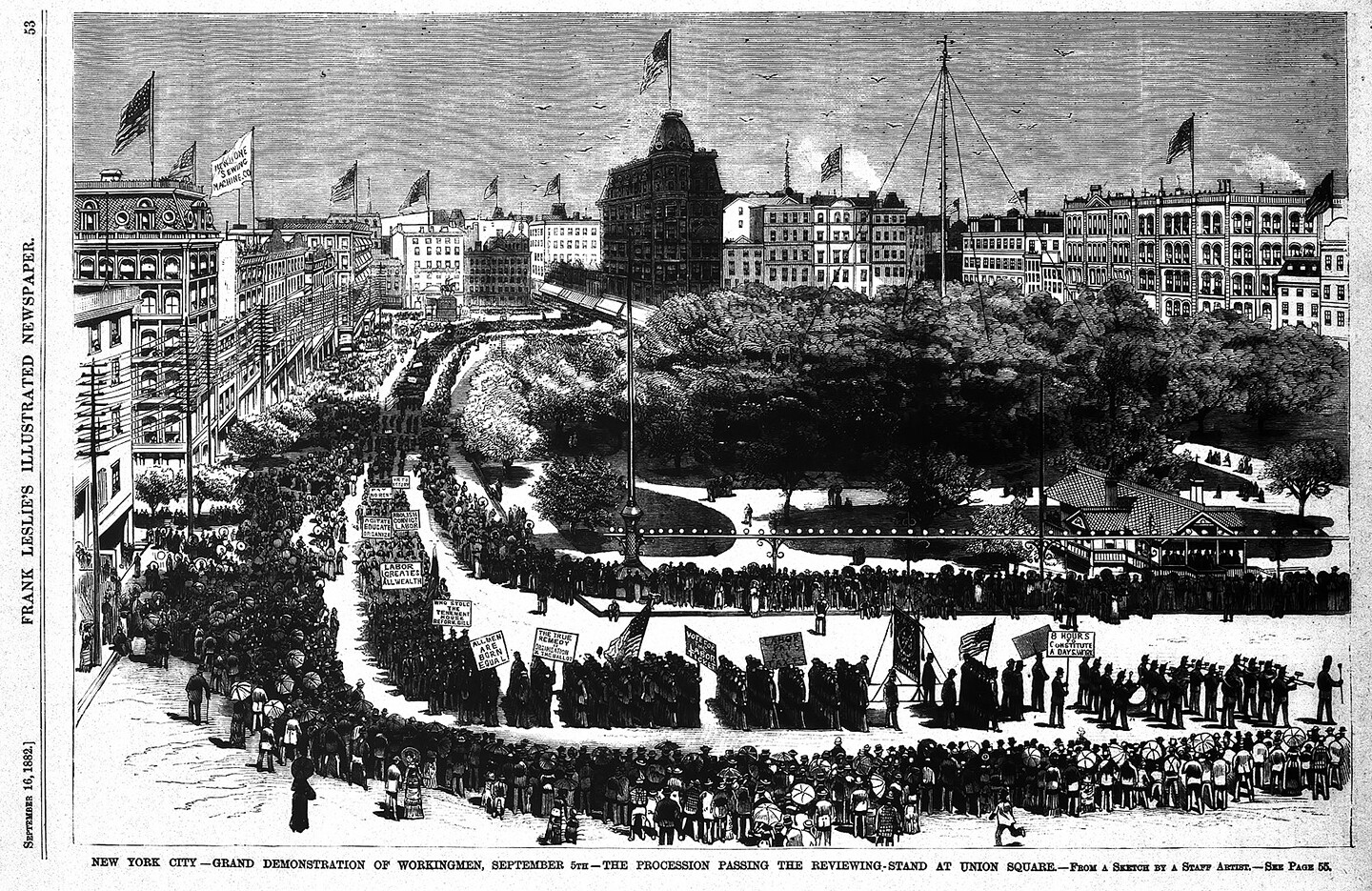

The workers movement wasn’t defeated by capitalism. The workers movement was defeated by democracy. This is the problem which the century puts to us. The matter in front of us, die Sache selbst, that we must now try to think through.

We are conditioned, even neurologically impaired, by what modernity does to us. But we are not determined by it; we can find other ways to rewire ourselves. This rewiring is a collective process; there’s no way an individual can do it alone.

This text might be framed as an offering, an attempt at releasing latent animist lines of possibility for what late twentieth-century works like Bronze Head might do for us in our current climate of rising anti-queer sentiment, on the African continent and elsewhere.

Long before Nazi violence came to be conceived as beyond comparison, Black radical thinkers sought to expand the historical and political imagination of an anti-fascist left by detailing how what could be perceived from a European or white vantage point as a radically new form of ideology and violence was in effect continuous with the history of (settler-)colonial dispossession and racial slavery.

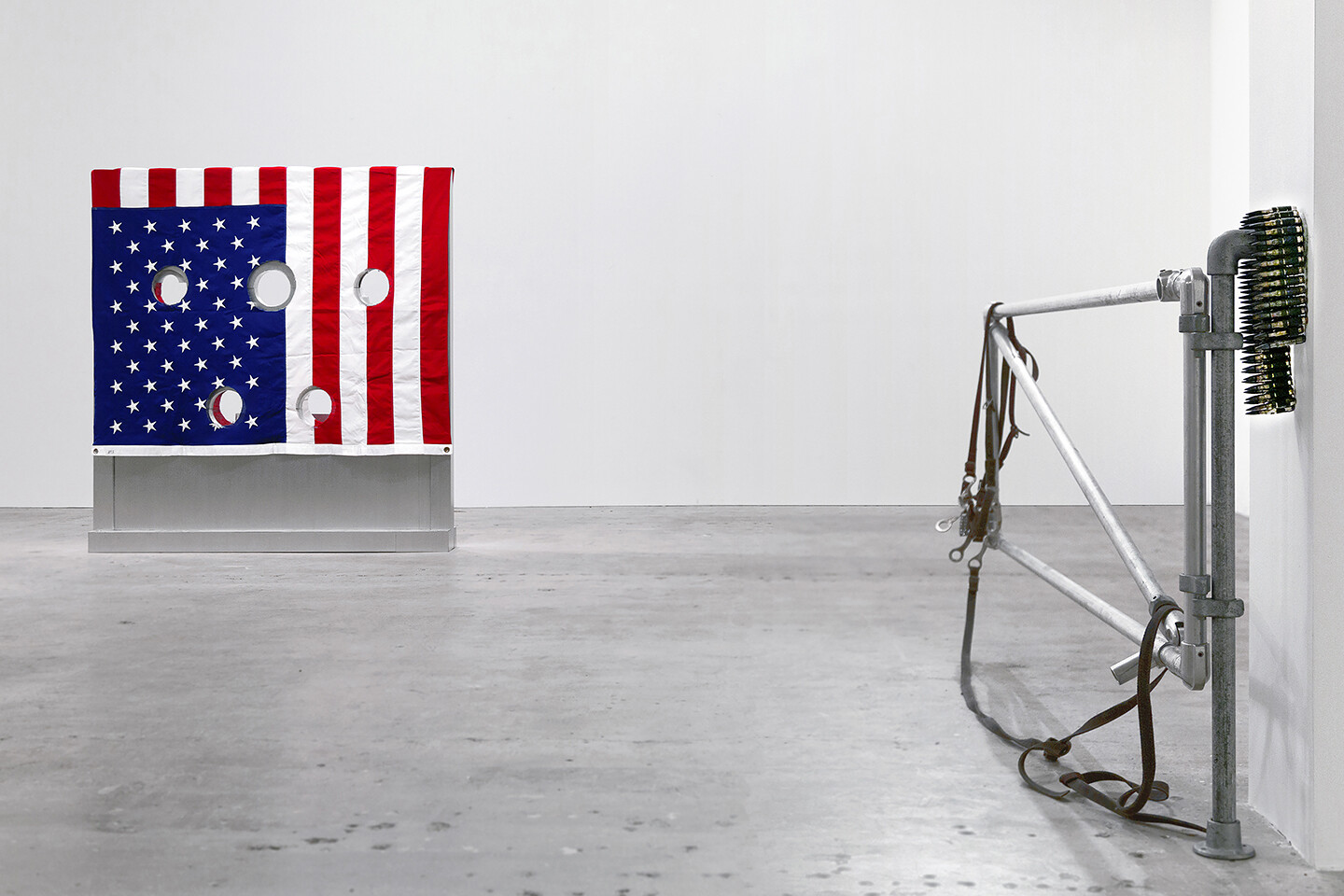

If many in the West today have the sense that the world is coming to an end, it is very much their world that is ending; other worlds were invaded and ripped apart long ago, yet the peoples in question refused to disappear—or, as with the Creole populations of the Caribbean, they became an unprecedented people spanning several aboriginal pasts, the long present of (neo)colonialism, and uncertain futures. Meanwhile the extractivist machine keeps accelerating—even amidst the symptoms of planetary collapse. The million-dollar question—to use an inappropriate metaphor—is to what extent contemporary forms of asymmetrical schismogenesis can maintain or produce forms of life in opposition to financialized and racialized capitalism.

Today I present a different figure, something like the unborn child’s bizarro cousin who is both real and unreal at the same time—the figure of a human life never even conceived. I call it the never-born. It exists but only in the minds of the already born and possesses no material manifestation whatsoever. No sperm hooking up with egg, no embryo, no fetus, no natal development, no forty weeks, no moment of birth, no child to care for, no adult in the making, no mortality to face.