What Caused the Crisis of Theories of Emancipation?

The current war in Ukraine has revealed numerous inconsistencies in certain left-leaning political theories—theories that have been regarded as cornerstones of emancipatory thought and practice. These theories propose alternatives to liberal-democratic mantras of “real politics.”1 The liberal-democratic worldview at issue here is well known: Western democracy is an advanced and civilized form of social organization; representative democracy is preferable to autocracy; the UN and NATO are alliances for collective defense; the democratic West supports the removal of autocratic regimes.

Since 1989, many of these liberal-democratic premises have been disputed. Some have been challenged as inapplicable to the struggles of disadvantaged social groups, for example. NATO has been criticized as a military alliance with a long history of imperialist interventions; representative democracy, some have pointed out, has been no obstacle to war crimes and is therefore remote from real democratic agency; and so on.2 Western modernity and even Marxist universalism have been put under suspicion for neglecting the true concerns of the Global South. Moreover, as the cultural left (meaning the writers, academics, and cultural workers who do not participate in political movements or party politics) has argued almost universally, the governments of representative democracies often behave as badly as autocratic governments, with little difference between the two.

With the war in Ukraine, the above-mentioned critiques have lost some traction, especially as they have been forced to confront the aspirations of people in post-socialist societies—Ukraine, Georgia, Moldova, the Baltic republics—to voluntarily orient themselves towards European democracy, NATO, and the EU, with all of their promised social protections. In most cases, this desire on the part of these populations has not been the result of coercion by EU or US interests. Rather, it has generally been an autonomous civil aspiration to use the West as a way to escape Russia’s paternalist control. This strong aspiration for entry into NATO and the EU in some post-Soviet states was provoked not only by the fall of state communism, but also by the widely held conviction that affiliation with the EU represents a path to a more advanced form of contemporary civilized sociality.

After 1989, the populations of several post-socialist states—among them Estonia, Lithuania, Latvia, Georgia, Moldova, and Ukraine—came to see NATO as the greatest safeguard for their newly established sovereignty and independence from the Kremlin’s expansionist policies, which continued after the Iron Curtain came down. Compared to post-Soviet oligarchic dictatorships, which restrict liberties and independent media completely, even neoliberalism came to be seen by such people as the lesser of two evils, and one worth fighting for.

This leads to my central point: it is important to dispute arguments that see the present conflict in Ukraine as merely a proxy war between two empires—on the one hand, the US, EU, and NATO, and on the other, Russia. Arguments that ascribe definite blame for the conflict to NATO also tend to underestimate and disrespect struggles for independence in post-socialist countries, depriving them of political subjectivity. According to these views, the aspirations of Ukraine, Georgia, Moldova, and other countries towards NATO membership and EU candidacy have no agency of their own, which implies that these voices are unimportant. Moreover, blaming NATO for the Russian invasion underestimates the Russian Federation’s responsibility for its vicious imperialist policies.

US navy war ship USS Simpson sails with the NATO fleet in the Adriatic Sea during Operation Sharp Guard, a blockade on shipments to the former Yugoslavia, 1995. License: Public domain.

Ironically, Western “leftist” voices who claim that so-called Western values—representative democracy, freedom of speech, LGBTQ rights—would not bring any considerable changes to the lives of people living under post-Soviet autocracy usually live in the West and take advantage of those rights, however imperfect they may be.

However, the inability of some segments of the cultural left to recognize the new conditions of “real politics” is understandable. For decades, their discursive work was grounded in a critique of Western liberal democracy, and for good reason. However, after February 24, 2022, when Russia pierced the Ukrainian border, a mere critique of neoliberalism is no longer sufficient for developing a critical perspective on the situation in Eastern Europe, given that the post-socialist countries are at present much more endangered by their quasi-feudal oligarchies and autocratic repression than by liberal democracy. In other words, I am arguing that in a paradoxical twist of fate, liberals seem to have a greater understanding of real politics today than the (cultural) left, which historically had the task of organizing workers and other destitute populations to negotiate their participation in emancipatory politics. The comfortable position that allowed the cultural left to confirm its emancipatory reputation outside the realm of real politics is no longer plausible.

After the collapse of the socialist project, Western social democracy came to be seen as the only relatively progressive option for confronting post-Soviet oligarchic autocracies and dictatorships. Responding to this political climate, most developed capitalist systems incorporated leftist cultural politics and institutional practices of social democracy, which some people have used as tools to confront neoliberalism and expand the domain of the commons. Cornelius Castoriadis showed very clearly that under global capitalist conditions, this is the primary relationship between capitalist economics and the emancipatory institutions that contest it.3

Of course, it is very tempting to create an imaginary realm free from capitalism. It is more productive, however, to start from an awareness that we are always already inscribed in capitalism, as a basis for developing realistic strategies for diminishing its impact.

Once the socialist system was rejected, building an efficient capitalist system was the only option for post-socialist countries against post-Soviet nepotistic shadow economics. In other words, the course towards democracy in the post-socialist world has evolved under capitalist conditions. Because of this, in today’s context we must undertake a more orthodox historical-materialist analysis and accept that Western liberal democracy, with all its awful features, is more progressive than autocratic post-socialist “feudalism.”

The NATO Issue

According to numerous arguments from key left figures and publications in the West, NATO expansion into Eastern Europe was a historical mistake that triggered the Kremlin’s recent reaction.4 This implies that the Russian Federation and NATO are isomorphically equal counterparts. However, this reading of the situation is inaccurate for three reasons.

Firstly, even if there had been an unofficial agreement between Gorbachev and his Western counterparts in 1990 that NATO would not seek expansion, this agreement only held as long as NATO’s counterpart was the Soviet Union.5

Secondly, despite certain colonial features, the Soviet Union was not a nation-state but a confederation of states, held together by a socialist political economy rather than by classical nineteenth-century imperialist aspirations. Indeed, the role of the Soviet Union as a superpower of global influence rested on its ideological and social impact worldwide. In the ideological rivalry between capitalism and socialism, there was a tacit distribution of influences between the Western (capitalist and liberal-democratic) hemisphere and the Eastern/Southern (pro-socialist) hemisphere. It was thus the political-economic and ideological dimension of socialism that had an influence on real politics, rather than the aspirations of a single state. The Russian Federation, on the other hand, is a nation-state and cannot exert this same impact, because it cannot profess any international political idea similar to socialism (as the USSR did). Thus, the Kremlin’s belligerence today stems not so much from NATO expansion but from the inability of the Russian Federation, as a former major agent of world politics, to be content with being merely a federal nation-state. Russia’s desire to have both—to be a capitalist nation-state and preserve the pretension to influence the former socialist countries, or to identify the historical Soviet borders with the Russian ones—demonstrates the most malign and outdated imperialist aspirations.6 The expansion of NATO was thus an inevitable process triggered by the imperialist vision of an ideologically empty nation-state. If the NATO navy hadn’t entered the Black Sea in 2008, for example, Russian troops might have invaded Tbilisi, despite agreeing to a ceasefire with the Georgian government.

Thirdly, no Russian leader feared NATO invasion in 2011 or 2012—at least publicly. Indeed, in 2012 American leaders believed that they were pursuing a “reset” of relations with Russia.7 As Timothy Snyder argues,

In 2002 Putin spoke favorably of the European Union and avoided portraying NATO as an adversary. In 2004 Putin spoke of European Union membership for Ukraine, saying that such an outcome would be in Russia’s economic interest. He spoke of enlargement of the European Union as extending a zone of peace and prosperity to Russia’s borders. In 2008 he attended the NATO summit.8

These statements seem to suggest that NATO expansion was not a primary issue for Russian security at the time; it was rather a bargaining chip to use with the former satellite states (Ukraine, Georgia, Moldova), pressuring them to abandon their stated aspirations for closer relations with Europe. It is worth remembering that the Kremlin’s support for the Abkhaz separatists in Georgia in 1991–93 was not provoked by any aspiration by Georgia to join NATO or the EU. Georgia was actually planning to maintain its neutrality. However, even though Georgia initially refused to join the Commonwealth of Independent States—formed in 1991 by Russia and eleven other former Soviet countries, after the collapse of the USSR—later that same year Georgian president Eduard Shevardnadze signed a charter stating Georgia’s intention to eventually join the Commonwealth. As a result, Georgia was deprived of two of its regions—Abkhazia and Ossetia—and forced to become a satellite state of Russia, which was head of the Commonwealth. This situation continued until Mikhail Saakashvili, president of Georgia from 2004 to 2013, formally declined Commonwealth membership in 2009. Officially, under the USSR, Georgia and other republics were considered equal states. Back then, the fact that republics were satellites of Russia was tacit rather than formally acknowledged. However, after the formation of the Commonwealth in 1991, and a year later with the establishment of the Collective Security Treaty Organization, Yeltsin and then Putin coerced certain former Soviet republics (Armenia, the Central Asian countries) into membership. Putin wanted to do the same with Ukraine, Moldova, and Georgia, which would de facto contradict their sovereignty and independence. This is why these states revolted when they did.

Such inconsistent foreign-policy moves by Russia—claiming one thing and doing another, agreeing to international laws and then unexpectedly violating them—are part and parcel of the shadow tactics that the Kremlin has developed over the last twenty years. Putin’s government has used both legal and illegal tactics in the political management of conflicts in Georgia and Ukraine. Internally, Russian government officials claim that Ukraine and Russia are one nation, and that the Georgian regions of Abkhazia and Ossetia should be annexed. But externally, on the stage of international law, they support a legal resolution to these issues, at least for certain period of time—until suddenly they carry out the political decision they had already developed internally, irrespective of international law. In this way, an abrupt and illegal political step is made “legal” unilaterally, without coordination with any international political or legal institution.

It goes without saying that NATO’s military interventions in Iraq, Serbia, Libya, and elsewhere must be condemned according to a similar logic. Furthermore, NATO and EU membership didn’t prevent the rise of right-wing governments in Hungary, Croatia, or Poland. Nor did it protect Greece from financial crisis and ruinous debt, or diminish the need for Greek, Croatian, and Polish citizens to become migrant workers in more prosperous EU cities. Were Georgia, Ukraine, and Moldova to become EU members, this would not immediately solve the problem of the migration of their local populations to more prosperous Western countries. The hegemonies and tensions, even colonial relations, between the richer and poorer EU countries would remain. However, it is also clear that without alliances with the West, the economic and political situation in these countries would become much worse.

Autocracy vs. Democracy: The Variegated Uses of Surplus Value

The present war in Ukraine makes evident systemic differences between two forms of governance: antidemocratic isolationist autocracy, and globally oriented pro-Western liberal democracy. Certain political scientists (like Vladimir Pastukhov) assume that for Russia this military invasion is a strategy for inciting an internal civil war between pro-autocratic and pro-democratic social groups, which it can then export to other territories like Georgia, Ukraine, Moldova, and so on. The filmmaker and writer Oleksiy Radinsky also argues that the real problem of the present war is not so much rooted in Ukraine; it is embedded in the malign social mutations and inconsistensies within Russia that it exports to other post-Soviet states.9 Both autocratic governments and Western neoliberal ones affirm and reproduce capitalist economics. However, in Western liberal democracies there is a long history of counterbalancing neoliberal policies with social democratic programs, civic agencies, progressive taxation, spending by nongovernmental institutions—to uneven degrees of course. In such countries, especially those with strong social-democratic and nongovernmental institutions, the middle and lower classes have a relative ability to form civic networks and collective agency. In autocratic societies like Russia, class confrontation plays out less between the rich and poor than between autocratic ruling groups united with the “people” (including socially vulnerable populations), and the educated and internationally oriented middle class. As has been noted by many observers inside and outside such regimes, autocratic rulers often paradoxically manage to gain political legitimacy by espousing what sounds like anti-capitalist critique. Indeed, this is a method for dismissing democracy, by equating it with “Western capitalist perversities” or by pointing to the existence of social and economic injustice in Western countries—injustice that mirrors the autocrats’ own but is erroneously differentiated.

While the production of surplus value governs economic policy in the US and EU just like in Russia, Kazakhstan, Iran, or Saudi Arabia, autocratic governments and Western liberal democracies distribute it in very different ways. As Boris Kagarlitsky emphasizes, in contemporary liberal democracies—especially in their social-democratic variants—the surplus is partially invested in municipal infrastructure, education, technology, contemporary culture, and so on, even if unevenly and conditioned by the capitalist logic of property. In post-socialist autocracies, however, surplus funds are almost always embezzled, invested in luxury commodities and private infrastructure, directed to the military, or transferred as assets to neighboring former socialist countries (like Georgia and Ukraine).10 Typically, this last mechanism functions as follows: the Russian government purchases a business in a neighboring former Soviet republic while also bribing a politician to lobby for that business. As Kagarlitsky says, even if only a few people are corrupt in such a system, corruption becomes the basic operating principle of the whole system. When it is impossible to effectively invest money into upgrading economic and social infrastructures, it can only be embezzled.

Desiring the Facade

After the invasion of Ukraine, many wondered about Russia’s motives: major Russian cities were bursting with money and the urban middle classes were relatively well-off and didn’t engage with official political life. In February 2022, Moscow was ranked first in urban infrastructure development and quality of life by the United Nations Human Settlement Program. Crimea, the Luhansk People’s Republic, and the Donetsk People’s Republic had already been annexed. Why would Russia so cataclysmically jeopardize its prosperity and its impunity for these imperial crimes in exchange for the vague possibility of preventing Ukraine’s pro-Western drift by military means? This is a thorny question to formulate, let alone answer. But the reality of the invasion and the broad public support it currently enjoys in Russia demonstrates that the material conditions for this war were in place long before 2023.

In December 2011, large protests broke out in Moscow against what was perceived as a rigged election. After these protests, the Russian political class sought to quiet the unrest through investment in urban consumerist infrastructure. Instead of investing in the development of a professional meritocracy (something that liberal proselytizers like Sergey Guriev and Alexander Navalny have called for), Putinist urban technocrats focused on developing consumer luxuries and cultural recreation. In the Putinist system, access to versatile modes of consumption acts as a substitute for the development of technology and social agency. This is the logic of the Potemkin village carried into the autocratic present: the facade is enough, regardless of the content behind it. Here is where the population of the major Russian cities comes to a vicious consensus with power. In his analysis of Putinism, political theorist Ilya Budraitskis paraphrases Hannah Arendt from The Origins of Totalitarianism: “For Arendt,” writes Budraitskis, “the essence of fascist totalitarian society is not the penetration of politics into all social life, but rather the ultimate depoliticization.”11 Even when urban-dwellers do not support the Kremlin’s decisions, they are more or less content with the new facade—a higher quality of life (for some), clean streets, access to digital technology and diverse services, and perhaps most notably the omnipresence of contemporary culture and art. Thus, consumption connoisseurship has come to define the path to being a successful contemporary citizen in Russia. Outside the main centers of power and wealth, the citizens of poorer regions have also gained access to new forms of consumption, which have alleviated some resentment toward the elites.

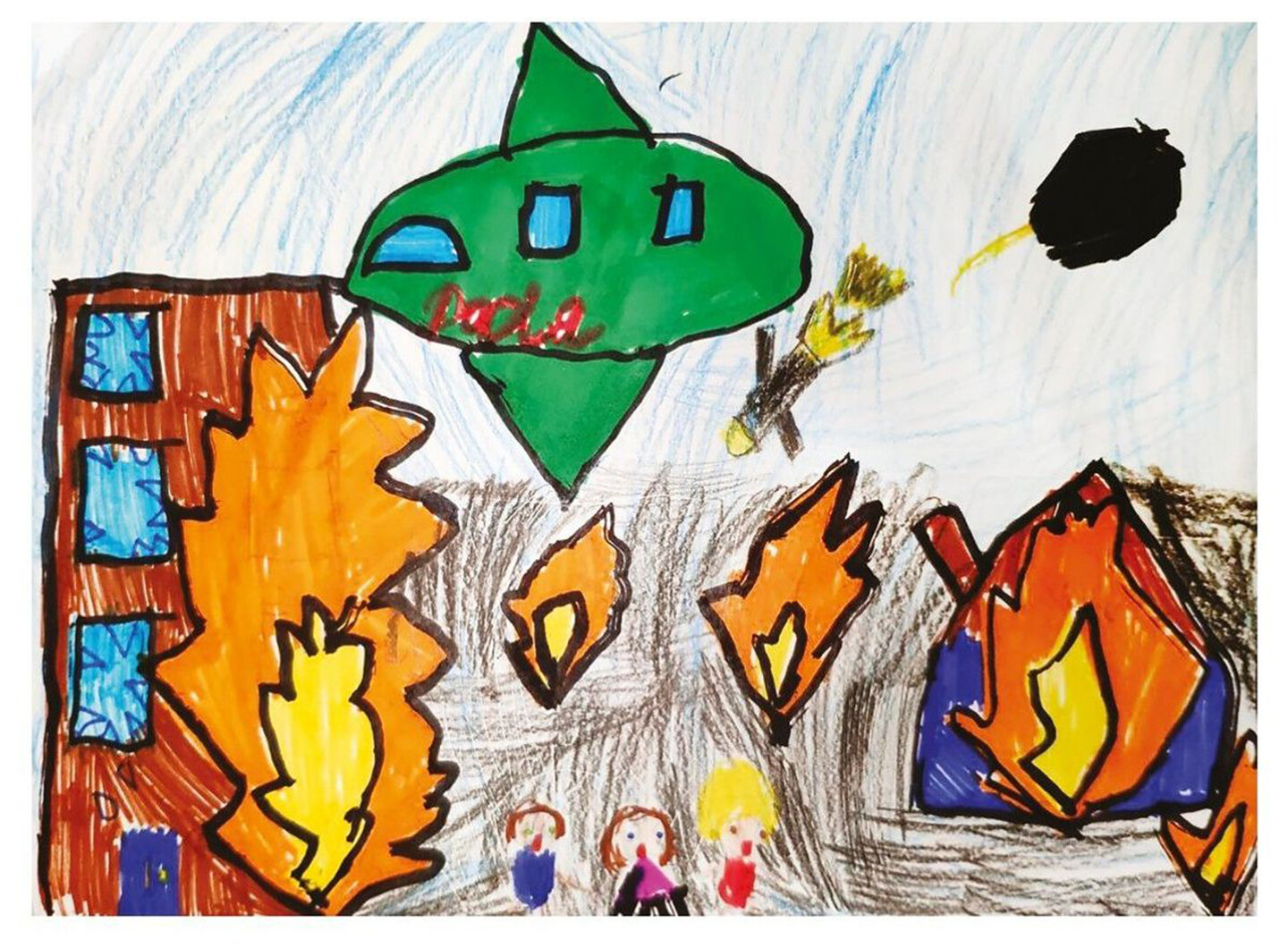

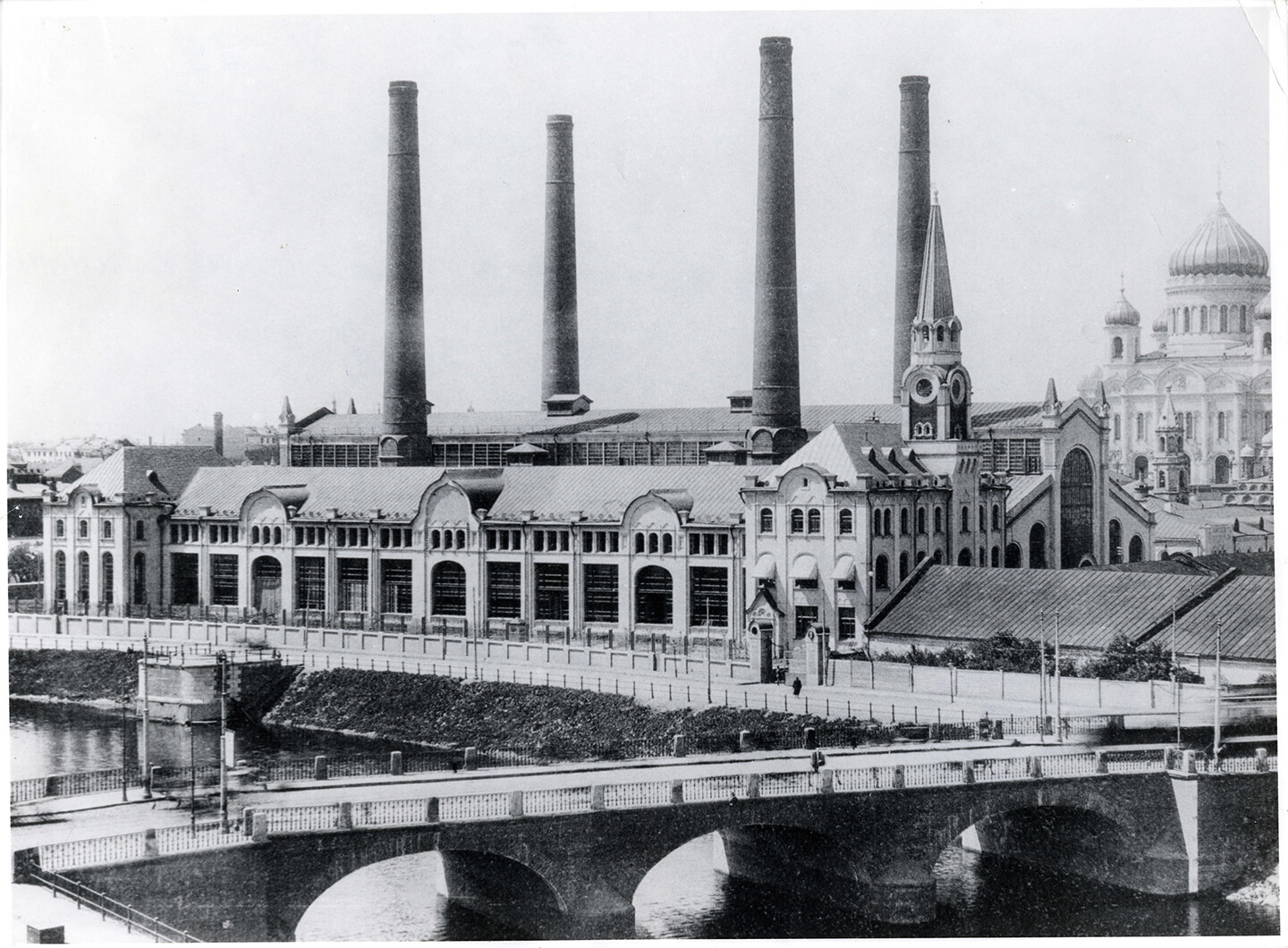

Moscow even became enticing to Western cultural workers, who willingly frequented its cultural venues and came to enjoy its glamorous hotels and restaurants. On December 3, 2021, three months before the invasion, Moscow saw the opening of a luxurious cultural institution, GES-2 (financed by oligarch Leonid Mikhelson). The grand opening was attended by an enormous number of prominent art workers from all over the world. The foreign guests competed to be involved with or employed by GES-2 projects. Again, a glossy facade concealed a shadow capitalism that had no interest in actually developing productive industry or social and technical infrastructure.

GES-2 power plant before it was converted into a contemporary art venue, Moscow, date unknown.

Indeed, the principle device of Putinist political technology is the manipulation of semantics to shape appearances, where any signifier or term can be imposed on any event, thing, or situation. This is the context in which a Federal Security Service worker can pretend to be an art historian, an orchestra conductor can be introduced as a curator, and an aggressor can be called a victim.

Unfortunately, voluntarily or not, Russian contemporary art has been compliant with such manipulations—and in many cases has employed the same techniques. My Western colleagues often asked me how GES 2 and the Garage Museum in Moscow managed to achieve such high levels of attendance—levels that seem unattainable to many Western contemporary art centers. The reason, to my mind, is that after the first Moscow Biennale in 2005, contemporary art in Russia became part and parcel of the consumerist paradise of the megapolis. It was associated with social prestige, thus garnering a huge amount of money from private and public sources. Art and culture enhanced the consumerist standards of the city, while expanded consumption allowed policymakers to integrate culture and art into economic planning.

Numerous art projects in Moscow, St. Petersburg, and Ekaterinburg that at first seemed cutting edge and attracted progressive international artists, curators, and theorists often forcefully marginalized longstanding forms of artistic and intellectual expertise in Russia. What was ousted was not so much grassroots art production but rather the credentialed experts, creators, and inventors of the intellectual and artistic milieu that emerged at the end of the 1980s and continued until the mid-2000s. Indeed, it was in the mid-2000s when the living process of cultural and intellectual production in Russia was hijacked, first by big capital and then by the state. Today, most positions in museums and other important cultural institutions are filled by technocrats or other nonart workers. Even though cultural workers in Russia have mourned the recent resignations of Pushkin Museum director Marina Loshak and Tretyakov Gallery head Zelfira Tregulova, it must be said that their appointment already marked the evacuation of the cultural and intellectual sphere of experts. Figures like Loshak and Tregulova occupied the artistic space that had been earlier created by others. By 2015, for example, there was not a single practicing curator in charge of any Russian contemporary art institution, only managers on good terms with the Ministry of Culture.

Three Factors in the Electoral Support for Post-Socialist Autocracies

How is it that the most wealthy representatives of the ruling class, whose immense fortunes had been made through the criminal abuse of limited resources and negligence towards underprivileged populations, are supported by the majority of voters in post-Soviet autocracies? I would point to three factors.

The first lies in the association of freedom with the right to ignore the law. For self-made post-socialist entrepreneurs, the arrival of democracy was associated with freedom from the law and taxation, freedom from any civic responsibility and transparency about the source of one’s wealth. Such freedom implied legitimizing the shadow areas that were criminalized during the socialist period but nevertheless thrived in the underground economy. When post-Soviet elites saw that accumulation and enrichment were not sufficient for building capitalist democracy, post-Soviet governments and the newly enriched oligarchs reverted to kinship-based relations. For example, numerous Georgian oligarchs used to be “thieves in law” and members of the shadow mafia. As soon as their sources of wealth had to be made transparent, they became enemies of Western democracy and even ardent “critics” of capitalism. It is therefore understandable why the post-Soviet communist parties and certain leftist groups seem to be more loyal to local clans and oligarchs than to Western neoliberalism grounded in law: they think they are siding with a less developed capitalism, against a more advanced one.

The second factor follows directly from the first: the illegal post-Soviet privatization and then random distribution of the former social wealth among private owners caused both extreme pauperization and extreme enrichment among former Soviet populations. In the post-Soviet period, democracy was therefore often associated with this economic injustice. Putin managed to deflect the guilt and blame for privatization onto Yeltsin’s government; Putin associated himself instead with a return to social guarantees reminiscent of state socialism. Paradoxically, Yeltsin’s government—which is considered to be more liberal and democratic than Putin’s—was not very supportive of the unprivileged, whereas Putin first gained electoral support by attending to public employees (e.g., by indexing the salaries of educational and medical workers to inflation and by preserving free health care). For post-socialist liberal democrats, the struggle against Soviet totalitarianism entailed the complete demolition of the Soviet social sphere, including the cornerstones of a de-privatized social state: free education, free health care, free housing. As they privatized industrial production, media, and public services, they did not notice that they merely deprived the bulk of the population of social guarantees. The biggest revolt against the capitalist democratic changes took place in October 1993 in Moscow. This is when the Supreme Soviet disobeyed Yeltsin, who planned to dissolve it in order to create a new parliament, which was needed to legalize privatization. Protests broke out in defense of the Supreme Soviet. They were ruthlessly suppressed: 154 people were killed and even more wounded. In short, post-Soviet liberals ignored social-democratic programs, which are usually part and parcel of European democracy. It is no surprise then that the unprivileged populations united around the paternalist political forces that guaranteed at least some minimal social spending. As Dmitry Muratov remarks, when in democratic societies welfare diminishes and people get poorer, they usually put pressure on their governments. In autocratic societies—in Russia most visibly but not exclusively—the poorer people are, the more they unite around authority in the expectation of some small reward.

The third factor is more complex. It has to do with the split between official politics and the spheres of civic emancipatory autonomy. Citizens of Western democracies—despite the many deviations from democracy in these countries—have legacies and traditions that exist outside the sphere of the state, in public and nongovernmental spheres. These nongovernmental spheres nudge governments against austerity and various kinds of discrimination and supremacy. Here, civic life is not confined to social assistance but presupposes intellectual work, public agonism, and an expanded body of critique. Chantal Mouffe and Ernesto Laclau, in Hegemony and Socialist Strategy and elsewhere, discuss the forms of public agonism at length. Even with the considerable drawbacks of capitalist democracy and its limited response to emancipatory demands, public debate is not censured by the state in Western democracies. As a result, the gap between intellectual workers practicing emancipatory critique and various sorts of laymen is lessened. In Russia, Belorussia, and other autocratic political systems, the gap between educated cultural workers and other communities—be they richer or poorer—is vast. As stated above, in autocracies social segregation is not between the poor and the rich but between the enlightened middle class/intellectuals and the rest, regardless of their income. In the absence of powerful left-leaning and progressive opposition in parliament, the “people” side with the paternalist autocracy.

The present war crystalizes the division between two social domains: on one side, liberals, critical intellectuals, and contemporary art workers (often with left-leaning politics); on the other, political and business elites, official cultural workers, and the majority of the population. Each of these domains refuses to recognize or legitimize the social representation of the other.

Catastrophe

The formula for the present catastrophe of Russia is the transformation of socialist and post-socialist reality into a quasi-fascist phenomenon: the most unprivileged social groups side with the ruling elites and become the electorate of corrupt autocratic oligarchies. They support war and imperialist expansion, homophobia, clericalism, and anti-Western xenophobia. Meanwhile, the enlightened and globalized intelligentsia, as well as the former meritocracy (i.e., the critical middle class, which of course encompasses not only liberals but left-leaning students and cultural workers), supports human rights, civil liberties, and emancipation. They consequently become outcasts or exiles.

Interestingly, the social composition of the 1917 revolution was different. At that time, the left-leaning middle class managed to find a shared language with the proletariat. We, the intelligentsia today, haven’t managed to form such a continuity with the unprivileged layers of society in Russia. Nor have we managed to construct any agonal buffer zones in the cultural and artistic sphere to influence emancipatory transformation. Navalny’s program was a very basic attempt to do so, but it focused much more on the denunciation of corruption than on social construction. Instead of building agonism on the cultural terrain, we allowed the state and pro-state private capital to appropriate the sphere of civil agency, until it was too late.

Considerable responsibility for the appropriation of the civic sphere by the regime lies with several liberal politicians of Yeltsin’s time. After Putin’s appointment, they preferred to serve his government rather than contribute to the parliamentary opposition when they still had agency and visibility. Some of them even participated in bringing Putin to power. In fact, the liberal political technocrats—such as Gleb Pavlovsky (Foundation of Effective Politics), Stanislav Belkovsky (Institute of National Strategy of Russia), Marat Gelman (gallerist, another founder of the Foundation of Effective Politics, and deputy director of Channel One Russia), and Anatoly Chubais (Rosnano Group)—were the principle architects of the initial stage of Putin’s power. They all threw their weight behind the empowering of Putin’s regime, only joining the liberal opposition after Putin got rid of them.12 As the liberals often themselves acknowledge, they helped Putin to make the autonomous leftist (socialist) opposition vanish completely. Paradoxically, their contribution brought about an unexpected effect: the leftist parliamentary and non-parliamentary opposition was subsumed by the autocratic and military elite. Due to the neutralization of leftist and social-democratic viewpoints, the discourse of social justice was usurped by the regime, while the absence of a liberal opposition enhanced the power of the military and security services.

In Fascism in its Epoch, Ernst Nolte argues that the fascist turn in German politics came about because liberals ousted leftists from the political-economic arena. In Russia, the situation was similar: the state, having transformed itself into a militarized dictatorship, expelled not only left-liberals and communists but also competitive market economics, subsuming both capitalist democracy and socialist politics.

The Russian political situation of the last ten to fifteen years is in many respects reminiscent of Germany in the 1930s. Meanwhile, emancipatory theory and the contemporary global left have reached an impasse: while they fairly criticize both capitalism and right-wing politics, they regard the abolition of private property and capitalist surplus-value economics—the political-economic achievements of the October Revolution—as coercive and totalitarian. In other words, the cultural left claims to be against capitalism but at the same time opposes the revolutionary abolition of capitalist economics. The left’s dismissal of the radical anti-capitalist political-economic changes initiated by the Third International after 1917 demonstrates that equality politics without these political-economic transformations is possible only with the preservation of the capitalist condition, regulated by social-democratic institutions. The global left thus associates emancipatory politics with the Menshevik stance. If this is true, then the politics of emancipation and social justice can only exist under conditions of capitalist democracy—a formula that is the inevitable status quo of post-socialist global politics. Consequently, it is inconsistent for the left to denounce Western liberal democracy and sneer at the EU aspirations of post-Soviet republics without providing a radical political-economic alternative—as the Marxists did in 1917.

By “theories of emancipation” I refer to an array of critical and political theories that propose anti-capitalist ideologies and practices that go beyond liberal-democratic politics and the arena of “real politics”—the arena of executive state power exercised through official government institutions.

For an example of these kinds of critiques, see DIEM 25, a pan-European direct-democracy movement founded in 2016 by, among others, former finance minister of Greece Yanis Varoufakis →.

Cornelius Castoriadis, The Imaginary Institution of Society (Polity Press, 1987).

For examples see this interview with Noam Chomsky →; and Benjamin Schwartz and Christopher Layne, “Why Are We in Ukraine?: On the Dangers of American Hubris,” Harper’s Magazine, June 2023.

According to unconfirmed discussions, Gorbachev acceded to the unification of Germany on the condition that NATO not pursue expansion.

At an awards ceremony for the Russian Geographic Society six years ago, Putin asked a schoolboy where Russia’s borders ended. The boy responded nervously in front of a crowd that they ended after the Bering Strait, just before the US. Not quite, Putin retorted: “Russia’s borders never end” →.

Timothy Snyder, The Road to Unfreedom (Tim Duggan Books, 2018), 48.

Snyder, The Road to Unfreedom, 42.

Oleksiy Radynski, “The Case Against the Russia Federation: One Year Later,” e-flux notes, May 15, 2023 →.

Boris Kagarlitsky spoke about this in an interview with K. Sobchak → (in Russian).

Ilya Budraitskis, “Putinism: A New Form of Fascism?” Spectre, October 27, 2022 →.

Marat Gelman participated in the Ukrainian electoral campaigns of Viktor Medvedchuk (2001) and Victor Yanukovich (2004).