1. Gotham Subway

In 1975, a critic complained that some of the poems in Audre Lorde’s New York Head Shop and Museum (1974) were “not what one expects from Lorde”—who was nominated for the National Book Award for poetry a year earlier.1 Still, the reviewer said that a study of the influence of New York City on Black poetry should be written and that it must include Lorde. The book came out on Broadside Press, founded in 1965 by Detroit-based poet and editor Dudley Randall, a monumental figure in the Black poetry movement. Judging by the lukewarm response, perhaps some felt that Lorde had gone too far in her unsparing depiction of New York as a “beleaguered city.” New York Head Shop and Museum is far from an optimistic Beat-generation volume; Lorde’s is an opposite picture to Frank O’Hara’s 1954 depiction of architectonic space in the “mountains of New York.”2 Two decades after O’Hara, Lorde provides stark images of death and survival in Gotham. It is a different city. In Poetry Magazine, another reviewer of New York Head Shop and Museum made much of Lorde’s alienation from the city on account of her race, gender, and her vocation as a poet: “Lorde is of course an outsider in more ways than one.”3 Neither reviewer made much sense of the poet’s complicated relationship to New York City. However, as scholar Alexis Pauline Gumbs has argued, Lorde’s intent is to engage deeply with the city as a metaphor that can illustrate the resilience of Black life in squalid and punishing labor conditions.4 In this way, Gumbs seems to suggest that Lorde’s literary strategies are effective in ways that transcend the model set by O’Hara and the rest of the New York School poets. She may thrive in a modernist lexicon already established by the New York School, but she embraces modernism while simultaneously rejecting the city’s display of empire and of a capitalism that has genocidal tendencies towards the city’s Black, Indigenous, and Latinx residents. While predominantly known for her writing on feminist topics including care, sisterhood, breaking the silence, and sexual ethics, a lesser-known aspect of Lorde’s writing—which shows up in New York Head Shop and Museum—concerns Black spirituality, especially orishas that Lorde turns to while looking beyond empire from within its crumbling constraints.

In the backyard of a Brooklyn coffee shop this spring, I heard the queer immigrant poet danilo machado read poems centered on the New York City subway. Perhaps what drew me in was machado’s emphasis on poems about cruising on the subway, and the language appropriated from the Metropolitan Transportation Authority woven throughout machado’s concise 2023 volume, This is your receipt and is not a ticket for travel. We hear in these poems not only PA announcements from the Q line, but also the voice of the New York Police Department telling commuters: “If you see something, say something.” The subway voice is a kind of “consciousness” that infiltrates the speaker’s mind when reading the poems. We hear other voices too. In the coffee shop backyard, the audience burst out laughing when machado read a poem in which a protagonist hears two men gossiping within earshot on the subway platform: “biologically, it just leads to extinction”—a reference to homosexuality.5 Revisiting my encounter with machado’s poems has brought me back to the subway and to the issue of surveillance there, a theme that is prominent in their book. machado’s poetry presents sexual encounters that take place in subway cars. Cruising, in this setting, consists of communicating without words. It is done with the eyes. This focus on riders watching one another becomes a way for the poet to illustrate how desire meets with surveillance. machado has long been concerned with police surveillance, particularly regarding Black men, who are routinely stopped by police officers on the station platforms and in the subway cars.

machado’s poetry, rife with corporeality, eye contact, queer sex, witnessing, cruising, and naming police terror, paints a multifaceted picture of the subway. machado is also determined to hold subway officials accountable for facilitating state surveillance and racist violence. They invoke the forceful language of subway authority, which recalls the way Lorde depicts the vulnerability of Black bodies in the long aftermath of slavery. machado writes in “symphony (N to Astoria-Ditmars)”: “I closed my eyes and what opened / them was thinking about the conductor / whose consciousness I was deferring to.”6 What I understood when reading this poem was that machado embraces an American modernism, though one funneled through queer subculture—a subculture that includes writers like O’Hara, who perhaps went cruising on the subway too. O’Hara wrote that “subways are only fun when you’re feeling sexy,” and expressed the carefree joie de vivre of a flaneur: “The subway shoots onto a ramp overlooking the East River, the towers!”7

There’s a long history of the subway as literary setting. It can be found in the work of writers like O’Hara and John Ashbery but also Amiri Baraka and Ann Petry. In contrast to O’Hara, Baraka and Petry, also modernists in their own ways, were as interested in the subway’s racial violence as they were in its vividness and intimacy. Listening to machado on that spring evening in Brooklyn, I did not immediately think about Baraka’s play Dutchman (1964), perhaps because it has a more aggressive, urgent tone. In the play, a young Black man and a white woman get into a heated argument in a subway car. The woman’s remarks imply an increasingly violent racialization, which is echoed in the unfolding of the plot. Listening to machado’s lyrical though at times programmatic poems, I more readily recalled The Street (1946) by novelist Ann Petry. I thought about her engagement with modernism vis-à-vis the city, movement, and relationality. Set in World War II–era Harlem, The Street follows a single Black mother, Luttie, and her son, Bub, in their daily struggle to achieve the American dream despite violence and desperation magnified by racial, gender, and economic discrimination. I thought especially about Petry’s descriptions of the subway cars of the 1940s, with passengers getting off the subway at Lenox Avenue in Harlem, or a passenger boarding a subway train and picking up a discarded Black newspaper to read. In scholar Farah Jasmine Griffin’s articulation of the horizon of modernism through the lens of the Great Migration, Petry’s subway is depicted through sound and image. And the subway itself spurs the writer’s creativity. Griffin writes of Petry that “some days an idea or an image would appear as she rode the subway,” noting that the novelist was inspired by the “jolting of the subway cars on the long ride.”8 These writers present not only an architecture of movement but also an intimacy that can be risky. In their varied work, the subway is a space of adventure, newspaper reading, voyeurism, literary inspiration, and sex.

2. Gotham as Necropolis

By contrast, Audre Lorde saw Gotham and its subway tunnels through a dark lens. Her poem “New York City, 1970” shows a necropolis in which “murderous deacons” preside over “subway rush-hour temples.”9 Lorde’s New York is a city breaking down into ruins. “There is nothing beautiful left in the streets of this city,” she laments, which a page later becomes a refrain: “I walk down the withering limbs of my discarded house / and there is nothing worth salvage left in this city.” Her necropolis architecture interests me not merely because it is vulgar and filled with “stench” and “rats.” I view her disgust as evidence of Lorde’s own self-awakening, including her gradual political demoralization. Lorde’s drug-filled and rat-infested subway presents a scattered and fragmented rather than a whole and coherent architecture. Her architecture is a social and a bodily one, complete with “a needle in our flesh” and “horses in (our) brain(s).” Her visceral pictorial representation of the city is a far cry from the “urban renewal” promised by the likes of Robert Moses decades earlier. Instead, we are faced with bodies sent to the “gallows” and the manufacturing of “niggers.” The inherent violence of urban planning, among other forces in the city, is a continuation of genocide. Lorde’s language makes this clear. She knows that she and her children will be “tried as new steel is tried” and “the city shall try them / as the blood splash of a royal victim.” She is clear about the way the city exploits its (Black) labor. Lorde’s own self-awakening and her “bloody rush-hour subway revolution” takes place in poetry.

Lorde’s “beleaguered city” is a place where “broken down gods survive / in crevasses and mudpots” and where, evoking the long aftermath of slavery, bodies are carted to the “gallows,” when in truth “nobody wants to die.” Lorde’s poem is a stark departure from many earlier writers and philosophers who responded with enthusiasm to the formation of the modern state and modern city.10 Walter Benjamin, for example, believed in the potential of cities and mass media to bring about a new kind of producer, one not merely serving an industrial capitalist system.11 Others praised the workings of modern statecraft and modern architecture, despite the devastating removals, displacements, zoning, exclusions, and reclamations that characterized these formations. Lorde, with a view from deep into the twentieth century, instructs us to think about “broken down gods” and vulnerable Blacks “sent to the gallows.” The book’s dedication reads: “To the Chocolate People of America.” According to Gumbs, Lorde uses the cockroach as a metaphor to symbolize the persistence of Black life, “unbound by the limits of the patriarchal family or the internalized values of capitalism.”12

While one can attribute the somber mood of New York Head Shop and Museum to the various economic and political crises that would eventually lead the city to bankruptcy in 1975, there is something profound about Lorde’s meditation as a longer historical reflection of ongoing and untenable labor and living conditions that connote the continuation of slavery in the US. Lorde’s vision can be unsparing: “I condemn myself, and my loves / past and present / and the blessed enthusiasms of all my children / to this city / without reason or future / without hope / to be tried as the new steel is tried / before trusted to slaughter.”

Despite her bleak vision of the city, Lorde is also interested in the ways New Yorkers are connected by nourishment and intimacy, whatever their circumstances. In her Brighton Beach apartment, Lorde’s Jewish housemate, an old lady, teaches her how to boil stale corn in the husk. Combined with chicken feet stew, this makes Lorde fat.13 Elsewhere she tells her son Jonno to “cherish this city” and meditates on the “old men who shine shoes” and who “share their lunch with the birds.”14

Lorde’s engagement with the theme of intimacy in the city is expressed in lines such as “I am bound like an old lover—a true believer— / to this city’s death by accretion and slow ritual.”15 Like machado after her, Lorde bears witness to the many random and sometimes disturbing encounters that take place on the subway. She writes about a Black girl sitting next to her in the subway who nods off, high from taking cocaine: “A long-legged girl with a horse in her brain / slumps down beside me / begging to be ridden asleep / for the price of a midnight train free from desire.”16

Frances Clayton and Audre Lorde in an undated photo. Source unknown.

Her intimacy with the long-legged girl nodding off on the train also reveals the queer dimension of Lorde’s desire. Like in her Yoruba-inspired poem “Oya”—“I love you / now free me / quickly / before I destroy us”—the subject of desire here is female.17 Lorde’s first mention of her lesbian desire came in a 1970 poem titled “Martha.”18 Critic Barbara Smith wrote in her seminal essay “Toward a Black Feminist Criticism” that “Lorde had risked everything for the truth … I am not convinced that one can write explicitly as a Black lesbian and live to tell about it.”19 Even though four decades have gone by, this statement rings true today. It makes me ask whether it is possible to “attend to the work of Black women,” to quote critic Jessica Lynne.20 If anything, a study of the influence of New York City on poetry would reveal the dominance of white men and their joie de vivre.

3. No Longer at Ease

Lorde is no longer at ease in Gotham, to judge by her poetry. She asks us to riot if we’re fed up: “If we hate the rush hour subways / who ride them every day / why hasn’t there been a New York City Subway Riot / some bloody rush-hour revolution.” Lorde’s words are poetic utterances, and as such they are rooted in the imagination. The “bloody rush-hour revolution,” in my reading, is not meant literally. Her words regarding this “beleaguered city” are more cautionary than prophetic. At the time of her writing, New York City hadn’t seen a subway protest of the kind Lorde imagined. But there have been a few since, most recently in May of this year, after Jordan Neely, a Michael Jackson impersonator, was killed in the subway by a former US marine who put him in a choke hold.21 Lorde’s words about a “bloody rush-hour revolution” were written at a time, in the mid-seventies, when the activist strategies and contributions of Black women in the sixties were being strategically cannibalized by the women’s movement, and white women in particular.22

Lorde’s work from this time, however, is not limited to her grim picture of a 1970s Gotham rife with disempowerment. She simultaneously undertakes a more hopeful project—a search for the orisha spirits, the Black gods, and the Vodou and Santería priests that German anthropologist Hubert Fichte wrote about on his visit to New York in the seventies.23 This is the source of Lorde’s spiritual-ethical stance. She conjoins intimacy and sexuality with religious philosophy and ritual practice. Lorde’s complaint about “this city / without reason or future” also directs us to the Black gods—the exclusion of which was one of her major gripes with white feminists at the time.24

Lorde practiced rituals associated with the Yoruba orisha Oya and other deities. Her poetry points to African and Black spirituality as a locus of sensuality, corporeality, and intimacy. While these do not explicitly concern capital, labor, or law, they are political in the historical sense described by C. L. R. James and Brazilian philosopher Conceição Evaristo. Lorde was a follower of Oya, the goddess of the Niger River. (The Yoruba call a follower of Oya Aboyade, or “one who arrived with Oya.”) In Yoruba divination, like in Indigenous divination practices in Oceania and South America, bodies of water are often ascribed human characteristics and pronouns. In this case, the Niger River is described as a “she.” The followers of Oya and other deities treat the river with the same respect they would treat a person. These ways of being show respect to the environment and earth. It is also believed in Yoruba spiritual practice that Oya was a wife of Sango, a deity associated with fire and lightning. Myth states that Sango used Oya in battle, particularly for her ability to command the winds and thunder.

Lorde begins her poem “Oya,” which appears in New York Head Shop and Museum, by sketching out two characters who seem to be Sango and Oya, and who are called “mother” and “father.” This means that the poet identifies as Oya’s daughter. “My mother is sleeping,” Lorde writes. Throughout the poem we see the characteristics of both deities. We see how Sango is “my father / returning at midnight / out of tightening circles of anger.” We see “my mother / asleep on her thunders … Hymns of dream lie like bullets / in her nights’ weapons / the sacred steeples / of nightmare are secret and hidden.” Oya is a warrior whose nights are dedicated to dreams of strategy. Oya’s nightmares are sacred, secret, and hidden. The image of the warrior who dreams of strategies resonates with Lorde’s later statement that “self-preservation is an act of warfare.” Lorde then inserts herself into the line: “I too shall learn how to conquer yes.” With this statement, Lorde transforms her spiritual devotion into a weapon to use against the exploitative and violent regime that continues even in the aftermath of slavery. Lorde’s account of sex in the poem (“Yes yes god / damned / I love you / now free me / quickly / before I destroy us”) reveals desire, anger, strength, and character, all while remaining fully engaged in the battle for self-preservation.25

The necessity of this constant battle for self-preservation is perhaps why Lorde later declared, in a 1984 interview with James Baldwin, that “the [American] dream was never mine.” In her disappointment at this discovery, Lorde says, “I wept, I cried, I fought, I stormed.”26 While Lorde’s writing reveals her intellectual formation in psychology (her poetry is full of references to interior and psychic life) and post-structuralism (while she does not directly reference figures like Derrida and Foucault, Lorde’s conception of “difference”27 challenges the essentialism often deployed in the identity projects of Black power and American feminism), I want to argue that Lorde’s view of the American dream, like her view of New York City in New York Head Shop and Museum, is complicated by the fact that she understands that there is more. New York is not the last word. Her ritual practice and her Black theology point to the Caribbean and Africa. She isn’t just thinking about the Empire. Lorde is the Black child of migrants from the small island nation of Grenada, and that “Old Country” occupies a huge part of her imagination. By contrast, on the topic of the “country” Frank O’Hara wrote that “one need never leave the confines of New York to get all the greenery one wishes—I can’t even enjoy a blade of grass unless I know there’s a subway handy.”28

In New York Head Shop and Museum, Lorde reminds me of a young Chinua Achebe writing about what it means to be “no longer at ease.” Her work deals with the aftermath of slavery by confronting the ongoing genocidal tendencies of Gotham and advocating healing practices from African and Black spirituality. Achebe’s novel No Longer At Ease (1960)—a phrase lifted from T. S. Elliot’s poem “Journey of the Magi”—is the story of an Igbo man, Obi Okonkwo, who was educated in England. When he returns to his village in Nigeria, Obi engages in a battle between Western education and African ethics that is directly tied to intimacy. Obi’s romantic relationship with Clara, who is an osu, or outcast, transgresses Igbo ethics. Given that Achebe’s novels coincide with the movement for African independence after the Second World War, questions about “Westernization” are accompanied by those of “Africanization,” as Britain, France, Belgium, Portugal, and Italy exit the stage. Over a decade earlier, South African authors like Alan Patton and Peter Abrahams had written novels that exposed the suffering of Black people under oppressive white colonial regimes, but Achebe’s task was different. His was to imagine what came after. And he did this by portraying possibilities for what “modern” African ethics might look like. In an interview with Charles Rowell, Achebe states that Clara, Obi’s love interest, is not “unreasonable.”29 This was Achebe’s way of thinking through Igbo ethics. Clara represents an aporia or incommensurability within the plot itself. When she asks, “Do you know that you’re not supposed to marry someone like me?” Obi responds arrogantly: “Nonsense,” he spits out, before adding, “We’re beyond that; we’re civilized people.”30 Igbo values are incommensurable with Euro-modernity. Lorde too deals with the incommensurable, since she is unwilling to conform to the imperialism and violent negation of 1970s New York City. She too is “no longer at ease.” Remember that Lorde’s critical attitude towards Gotham, her necropolitan characterization of New York’s capitalist and genocidal violence, is antithetical to the jazzy and hip New York of the Beat poets that preceded her. Her work challenges postmodern ideas of architecture that revel in the “excitement” and the “neon lights” of grand cities like New York. She deconstructs the iconography of Euro-modernity, especially the New York subway. In this sense, Lorde’s architecture is disembodied, fragmented, scattered. It is a forensic architecture detailing rats and roaches—a city in disrepair.

4. A Search for Meaning in a Troubled World

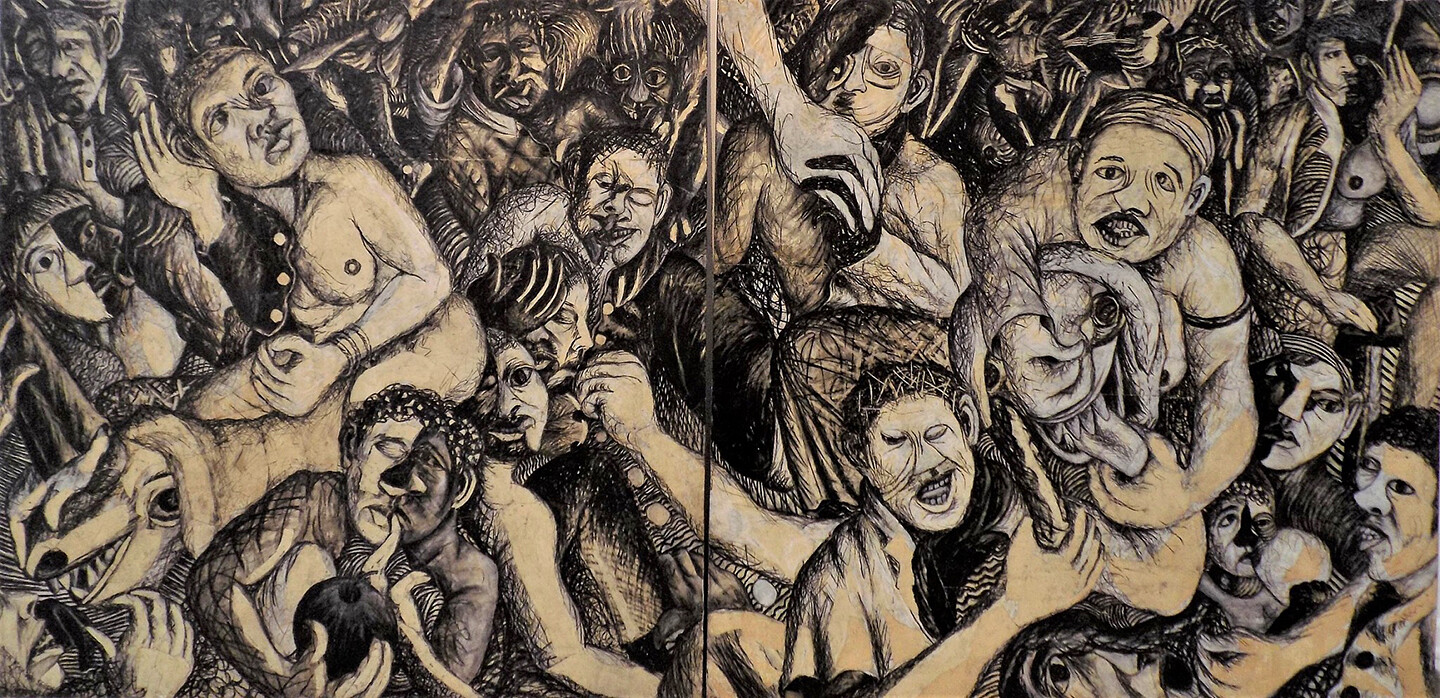

Lorde’s response to the violent regimes of modernity and hyper-capitalism reminds me of the artwork of Mmapula Mmakgabo Helen Sebidi (born 1943). Like Lorde in Gotham, Sebidi was no longer at ease in Egoli, South Africa. Sebidi painted and wrote during the South African crisis of the 1980s, which involved intensified armed struggle by the ANC guerrilla army, Mkhonto we Sizwe, and increasing police attacks on urban Black communities. Sebidi’s work reflects the violence that had taken hold in the townships. Similar to Lorde, her work straddles two fronts: one is urban space, specifically in the aftermath the Urban Areas Act that banned Black people from moving freely in South African cities without internal passports; the other is rural areas, with their connection to Setswana knowledge, the “Old Country,” and African diaspora wisdom. Elsewhere I have written about how Sebidi’s focus on the rural was misconstrued as being “without reason.”31 South African art historians portrayed what she had learned from her grandmother—mural painting techniques—as strictly formal instruction, without acknowledging how Setswana proverbs and the wisdom that accompanied such instruction comprised a form of knowing. The artist consciously incorporated this Sestwana knowledge into paintings such as The Mother Holds the Sharp Side of the Knife (1988–89). Regarding the artist’s relationship to the political climate of late-eighties South Africa, it is worth quoting at length from artist and curator Gabi Ngcobo’s critical comment on Sebidi’s painting Tears of Africa (1989):

Tears of Africa was created during a two-year period of self-imposed isolation. This was after Sebidi had enrolled for a creative writing course with, according to her instructor, undesirable results: too deranged to fathom and perhaps too big a responsibility to guide as a writing process. The body of work created during this time, more evident in Tears of Africa, resounds the personal as the political and vice-versa. It is an accumulation of her inner turmoil that was being released. This enunciation of subjectivity was paralleled with conflicts that were unfolding at the time in South Africa and its neighboring countries—conjointly with struggles that have marked the African continent, from slavery to the anti-colonial drive and the civil wars that ensued after political independence had been achieved. Much of this historical knowledge was not available in its detail to Sebidi, nor, undoubtedly, to most (Black) South Africans. The work came to be realized “outside of the realm of consciousness” but not outside that of responsibility for the youth in her teaching capacity and involvement in the artistic political climate as it was unfolding.32

Mmkgabo Helen Sebidi, Tears of Africa, 1989, 230 x 300 cm. Fundação Bienal de São Paulo.

The phrase “outside of the realm of consciousness” is derived from Félix Guattari: “The subject is not a straightforward matter; it is not sufficient to think in order to be as Descartes declares, since all sorts of other ways of existing have already established themselves outside of consciousness.”33 This repositions Setswana oral history, and what Ngcobo calls “an accumulation of inner turmoil,” at the forefront of a search for meaning in a troubled world.34 Per Ngcobo, this search spans “from slavery to the anti-colonial drive, and the civil wars that ensued after political independence had been achieved.” I am reminded here again of the aftermath of slavery and what Lorde describes, in one of her poems in New York Head Shop and Museum, as the seemingly ceaseless production of “niggers.” Ngcobo’s discussion of subjectivity and inner turmoil points to the kind of interiority that Lorde’s work depicts. Because for Lorde, with New York City falling into bankruptcy, the horizon of freedom slipped further into the distance. The gains of the Civil Rights era and the Black women’s movement of the 1960s seemed to be disappearing. Poems like “Oya,” in which Lorde writes about mother and father personas, echo Sebidi’s grandmother and her Setswana proverbs. Perhaps Lorde and Sebidi are also united in a “responsibility for the youth”—they were both teachers—and in their efforts to shape the direction of aesthetic production as crisis unfolds.

E. Ethelbert Miller, “Book Review: The New York Head Shop and Museum,” New Directions 2, no. 4 (1975) →.

Frank O’Hara, The Collected Poems of Frank O’Hara (University of California Press, 1995), 365.

Sandra M. Gilbert, “On the Edge of the Estate,” Poetry 129, no. 5 (February 1977).

Alexis Pauline Gumbs, “‘We Can Learn to Mother Ourselves’: The Queer Survival of Black Feminism, 1968–1996,” (PhD diss., Duke University, 2010), 156.

danilo machado, This is your receipt and is not a ticket for travel (Faint Line Press, 2023), 7.

machado, This is your receipt, 17.

O’Hara, Collected Poems, 365, 99.

Farah Jasmine Griffin, Harlem Nocturne: Women Artists and Progressive Politics (Civitas Books, 2013), 107.

Audre Lorde, “New York City, 1970,” The Collected Poems of Audre Lorde (W. W. Norton & Company, 1997), 101.

See for example Jean Jacques Rousseau, The Major Political Writings (University of Chicago Press, 2012); G. W. F. Hegel, Phenomenology of the Spirit (Oxford University Press, 1977); and Walter Benjamin, The Arcades Project (Belknap Press, 1999).

Benjamin, Arcades Project.

Gumbs, “‘We Can Learn to Mother Ourselves,’” 156.

Lorde, Collected Poems, 115.

Lorde, Collected Poems, 119.

Lorde, Collected Poems, 101.

Lorde, Collected Poems, 101.

Lorde, Collected Poems, 140.

Ann E. Reuman, “Cables to Rage,” in The Concise Oxford Companion to African American Literature, ed. William L. Andrews et al. (Oxford University Press, 1997), 63.

Barbara Smith, “Towards a Black Feminist Criticism,” The Radical Teacher, no. 7 (March 1978).

Jessica Lynne, “Finding Intimacy within Black Feminist Criticism,” Distributed Web of Care, 2017 →.

Edwin Rios, “New York Subway Rider Killed Performer via Chokehold, Authorities Say,” The Guardian, May 3, 2023 →.

Hortense J. Spillers et al., “‘Whatcha gonna do?’: Revisiting Mama’s Baby, Papa’s Maybe: An American Grammar Book: A Conversation with Hortense Spillers,” Women’s Studies Quarterly 35, no. 1–2 (2007).

Hubert Fichte, The Black City (Sternberg Press, 2018).

Audre Lorde, “An Open Letter to Mary Daly,” in Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches (Penguin, 2020).

Lorde, Collected Poems, 140.

Audre Lorde and James Baldwin, “Revolutionary Hope,” Essence Magazine, 1984.

“When a people share a common oppression, certain kinds of skill and joint defenses are developed. And if you survive you survive because those skills and defenses have worked. When you come into conflict over existing differences, there is ‘vulnerability’ to each other which is desperate and very deep. And that is what happens between Black men and women because we have certain weapons we have perfected together that white women and men have not shared.” Audre Lorde in Adrienne Rich, “An Interview with Audre Lorde,” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 6, no. 4 (1981).

O’Hara, Collected Poems, 197.

Charles Rowell, “An Interview with Chinua Achebe,” Callaloo 13, no. 1 (Winter 1990).

Chinua Achebe, No Longer at Ease (Heinemann Educational Publishers, 1960).

Serubiri Moses, “Counter-Imaginaries: ‘Women Artists on the Move,’ ‘Second to None,’ ‘Like A Virgin …,’” Afterall, no. 47 (2019).

Gabi Ngcobo, “A Question of Power: We Don’t Need Another Hero,” in 32nd bienal de São paulo: incerteza viva, ed. Jochen Volz and Júlia Rebouças (Fundação Bienal de São Paulo, 2016). Exhibition catalog.

Félix Guattari, The Three Ecologies (Athlone Press, 2000), 35.

Ngcobo, “A Question of Power.”

This text is an edited version of an online presentation delivered on April 25, 2023 for a panel called “Nobody Was Dreaming About Me,” associated with the exhibition “When We See Us: A Century of Black Portraiture” at the Zeitz Museum of Contemporary Art Africa.