Scenes from the Famine

1. The Discourse: Food as Identity

Facts about the famine:

–Four out of ten children residing in Lebanon face a lack of food security, according to Save the Children.1

–Human Rights Watch: “In more than one out of four households an adult had to skip a meal because there was not enough money or other resources to get food.”2

–46 percent of Lebanon’s population is hungry, according to the United Nations World Food Program.3

–According to the title of a recent article in The Economist, “In Lebanon, Parents Are Abandoning Their Children in Orphanages.”4

The specter of hunger returns to loom over Lebanon. This famine ushers in the modern nation-state’s expiry, the selfsame state that came into being after “people ate each other,” as some history books describe the famine of a hundred years ago.

We do not need to return to the famine at the beginning of the twentieth century to get a sense of the magnitude of our current social tragedies, just as we do not need images of our past civil war to discern the features of our current collapse. Returning to the past, especially through canned images, can be an obstacle to understanding the present, especially when this present is on the threshold of a massive transformation. Such a transformation begins with malnutrition and its disastrous effects (indicated by the statistics above) but extends beyond that to affect the process of producing and reproducing life in Lebanon.

2. Our “National Kitchen”

“Wherever we go in the world, we hear praise for Lebanese cooking, Lebanese food, Lebanese cuisine. It always comes up, as food that is appreciated by people.” This is how the host of the TV program Lebanon with a Story begins his conversation with a historian.5

The historian answers: “Lebanese food and oriental food … we say that it has soul. It is one of the only cuisines in the world that revives the soul, because we give it soul.”

Lebanon with a Story, a program on the TV station LBCI, paradoxically seeks to retell the ideological narrative of the birth of this nation at the moment of its historical fragmentation. Several other attempts in the media and the arts tell the tale of the Lebanese nation’s transformations in the twentieth century.6 What began as a celebration of Lebanon’s “story” quickly became, against the backdrop of the current collapse, an exercise in nostalgia—a yearning for a “golden era,” or an implicit lament for Lebanon’s lost master narrative. The above celebration of Lebanese cuisine, for example, was broadcast weeks after the publication of studies by international organizations on food insecurity, the increase in malnutrition, and the proliferation of hunger in the country. The celebration can also be read as a eulogy for a cuisine that no longer exists except on television, or in the diaspora, the last stronghold of this mythical story.

Maybe it was supposed to be a eulogy all along? What matters for this essay is the central role that Lebanese cuisine plays in the master narrative of the country. From the propaganda that addresses expatriates to the Ministry of Tourism’s campaigns and the so-called “biggest” competitions—i.e., the biggest plate of hummus or the biggest shawarma sandwich—food appears as a central component, if not the last bastion, of a worn-out national ideology. “Lebanese cuisine is like Lebanese citizens, vibrant and trendy, and the freshness of its ingredients and diversity of its colors and aromas seem like a celebration of life, renewed daily.” This is how a journalist encourages “food tourism” in Lebanon, in an article published in August 2019, a few months before the official start of the collapse.7 In building an image of this country that fits the role that the main nationalist ideologues envision for it—from mid-1950s Christian intellectuals to their postwar revival with Hariri’s neoliberal ideology—“Lebanese cuisine,” or the historical narrative about food and its meanings, came to embody the “Lebanese personality,” in its openness and renowned sense of hospitality and attachment to the family. It is also deployed to maintain emotional links with the diaspora as a constitutive component of Lebanese identity, and offers a lighthearted plane on which regional and sectarian competition can be safely performed.

The Question of Discourse

This image of Lebanon requires no critique. This story has become so rotten as to not even weather demystification. The mere co-occurrence of the ideology of excess, meze, and hospitality with the hunger suffered by 46 percent of the country’s population is sufficient to empty that ideology of any political content.

The climactic moment of this opulent narrative came in the middle of the last century. The postwar reign of prime minister and billionaire Rafic al-Hariri attempted to build on the narrative with its ideology of reconstruction. After his assassination, it was revived again in the so-called March 14 moment, when massive demonstrations broke out in Beirut. Nothing remains of this Lebanese story today except some television programs. Then the “revolution” tried, without knowing it, to salvage the remains of that story by feeding it some civil reforms and economic analyses. Today, we are no longer bound to this narrative through a relationship of power but rather through a relationship of nostalgia for a time when power had a narrative that could be dismantled.

Demonstrations in Lebanon triggered by the assassination of the former Lebanese prime minister Rafic al-Hariri on February 14, 2005. License: CC BY-SA 3.0.

Especially after the failure of this last attempt to fix things through reform, we need to reformulate a narrative about this country and its history that takes our troubled present as its point of departure. The “failure” of the revolution, in this sense, is the requisite entry point for a necessary rewriting of history.

INTERRUPTION

The Crisis in the Concept of Crisis

Much has been said about “the crisis” in Lebanon these days. The energy crisis, the cost-of-living crisis, the health care crisis. Add to this the presidential crisis, an institutional crisis, and a regime crisis. The surge in discourse about “the crisis” has become an obstacle to understanding our volatile reality, not to mention unpacking what we mean by the very concept of crisis.

The Dominant Semantics of Crisis

There are two definitions that dominate the deployment of the concept of crisis in the Lebanese media. The first is related to the political field, where the crisis is understood as a freezing, a vacuousness, or a paralysis. In this understanding, the crisis connotes a lack of movement on the level of politics, or more specifically, on the level of effective agency. Crisis here manifests in the inability of responsible powers to manage the conditions of the country, as a consequence of their institutional and political paralysis. Until the powers recover their effectiveness, society will remain bereft of any guidance or leadership, abandoned to face its tragedies alone. As for the second understanding, which is linked to social and economic themes, it is quantitative, and can be summarized with the following words: “decrease,” “unavailability,” “collapse.” Thus the crisis is a generalization of “scarcity”: power outages; shortages of gas, water, flour, etc.; a decline in purchasing power, social services, and growth indicators; a fall in currency rates, salaries, etc.

The relation between these definitions is causal. For “the paralysis” of power paved the way for society’s free fall; political paralysis leads to economic decline. The ideological aims of this theory become apparent in the reassertion of the hegemony of existing powers over society, through yoking any overcoming of the crisis—or even an analysis of it—to the return of institutions to their effectiveness, the same institutions and powers that are responsible in the first place for this crisis. “Where is the government?” is perhaps the slogan that most instantiates this crisis today.

Liberating the Crisis from the Dominant View

Perhaps we ought to replace the concepts of “paralysis” and “decline” with concepts that do more to actually illuminate the crisis. Perhaps we ought to approach the crisis from a different angle.

This crisis is not only a crisis of rule but is itself a tool of rule and management. The authorities exploit the crisis to discipline society and to pass unpopular policies without facing resistance. The current decision to maintain the crisis is not some mistake committed by political powers. Nor is it a consequence of a presidential vacancy or institutional paralysis. It is a conscious decision made by the authorities to restructure society without facing resistance, so as to reproduce their hegemony under new conditions.

The crisis is not only about scarcity or decreases, especially for the impoverished class. It is also about a revaluation of sectors and assets, which is what capitalist economic policies periodically require to kick-start the process of accumulation, no matter how much pain it causes. At such moments, the value of assets drops alongside the cost of labor, which in turn rekindles profits and accumulation. Here too our crisis is not a mistake but an economic necessity after the Lebanese economy came to a dead end.

When we begin to think of the crisis as a method of rule and an economic necessity for our model of capitalism, we begin to move away from the dominant view. The crisis no longer seems to be a natural disaster that befell us all, both ordinary people and authorities, but an economic and social process where the intention is to reassert the hegemony of the authorities over society’s resources while managing it with the least possible cost. The crisis is an opportunity for power. Were we not asked by the responsible powers to transform the 2020 port explosion into an opportunity?

Practice: The Family Fridge

The History of “Our National Cuisine”

No matter how sharp the contradictions of ideology are, they cannot be resolved on the plane of discourse. The “Lebanese narrative,” no matter how outdated it is, is above all a set of social practices and structures. And “Lebanese cuisine” is the best example of this. It is a discourse that loads food with meaning, so it can become a conduit for more than its original utility as nourishment through practices, rituals, and social structures that have grown around food consumption. Food may be the primary link between our emotional structure and our history. We learn, from childhood, how to associate certain tastes with feelings of intimacy and comfort, how to build relationships and social bonds around certain ways of eating, how to organize our days around our eating habits, how to bind religious and social occasions to certain eating rituals, how to produce our identity in the kitchen.

In his book Sweetness and Power: The Place of Sugar in Modern History, the anthropologist Sidney Mintz argues that transformations in dietary systems historically entailed “profound alterations in people’s images of themselves, their notions of the contrasting virtues of tradition and change, the fabric of their daily social life.”8 In this sense, what we are facing today is not simply a decrease in resources, the replacement of certain products, or the disappearance of certain foods. We are facing the beginning of a new social transformation that touches the simplest concepts and foundations of our social lives and our perceptions of ourselves.

There is no authentic cuisine, neither in Lebanon nor elsewhere. Food traditions are nothing but the result of long histories of economic and social transformations, some of which were compulsory. We cannot, for example, understand colonialism without learning about the history of manufacturing and trade in commodities such as sugar, spices, and coffee, or other such staple commodities. This is not only true in colonizing societies but also in colonized societies that received these ingredients and incorporated them into their own “national cuisines.” Likewise, we cannot understand transformations to cuisine without understanding the mobility of people, through migration and asylum, which brought with it flavors that are now considered “national” ingredients in the kitchens of host societies. National cuisines also change daily according to the policies of food production companies and state policies that regulate trade, or due to marketing strategies.9

Our cuisine, the supposed repository of our Lebanese identity, is the product of invasions and empires, the movements of peoples (mostly forced), as well as colonialism and its imposition of goods and resources. Our kitchen is witness to all this. But it is also the result of social and economic transformations that changed the rituals around food in response to transformations in the economic structure. Our relationship to our natural “heritage” transformed as a result of our local practices of capitalism and its opposition to agriculture in favor of other sectors. Our kitchen is also the result of technological transformations, from the introduction of the refrigerator, which became a central part of the kitchen, to the evolution in cooking and preservation techniques that changed our concept of cooking and the rituals that can be built around it.10

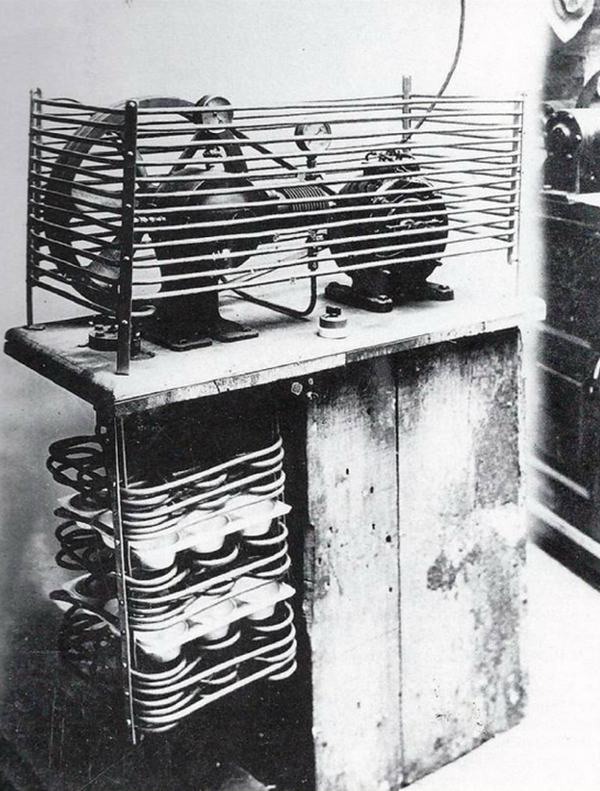

DOMELRE refrigerator c. 1914. License: Public domain.

Without a Refrigerator, There Is No Family

To focus on the history of our cuisine and its material foundations is to explore what the current crisis in our society is transforming without having to revert to prevalent theories of scarcity and decline.

Let’s pause for a moment with the fridge and what social transformations were enabled by the democratization of the ability to preserve and store food. The entry of the fridge into every home allowed for the separation of the relationship between production and consumption. This made it possible to store raw ingredients and animal products, which had no place in the home prior to refrigeration technology. The refrigerator became the technological condition for the development of an entire economic sector, that is, the food-consumption sector, built around the institution of the supermarket, the church of consumer capitalism.

Alongside other technological transformations, the fridge contributed to severing the relationship between eating and its natural rhythm. It became possible to consume all kinds of food year around, erasing the notion of “seasonal food.” Eventually, this concept would reappear by way of new-age restaurants and their “gentle” exploitation of food producers.

On the other hand, the refrigerator opened up the possibility of controlling the timeline of food production and consumption in homes, which contributed, along with other technical and social transformations, to liberating food products from the prison of the kitchen, releasing them into the prison house of the market. Subsequently, new “family” habits departed from the socially extended and interconnected family of the past. “Modern” families, consisting of parents and their children, reside in city apartments and orbit around the refrigerator and the TV.

So what does it mean when the refrigerator begins to disappear from our society due to the contemporary impossibility of securing electricity? In Hayy al-Tamlis, a neighborhood in Beirut, a resident tells me of families who no longer eat together because the refrigerator has disappeared from the house. We should perhaps pause to consider this remark about the entanglement between matter—the fridge—and the family, this sacred structure in our society. The family may be one of the most intimate structures in our society, but it has been changing for decades, adapting to historical shifts, and most recently, to the collapse. Some may still find it difficult to imagine that families transform, for family is the site of constancy. But let us recall the title of the Economist article mentioned earlier: “In Lebanon, Parents Are Abandoning Their Children in Orphanages.”

The Question of Practice

If we move away from discourse for a moment, and from the prevailing quantitative understanding of crisis, we notice that transformations in the structures of our society have begun at the level of practices that we cannot yet name. Practices change before discourse, so we still use old words to try and capture new practices. In the case of profound transformations, language fails us, as if it has expired. Here is the question we face: Outside of our defunct language, how do we begin to understand our new society, to capture its transformed features? If the “failure” of the revolution is the condition for the first question, then the completion of ceremonies of mourning for our former society is the condition for the second question.

INTERRUPTION

Classes and Lives

There may be some exaggeration, or an excess of theoretical rigor, in the link proposed between the fridge and the structure of the family. Electricity will come back, if not this year, then in the coming years. Things will return to how they were. But electricity will not return for everyone, just like the neighborhood generators are not available for everyone. More difficult to capture are the invisible transformations that permeate social structures like the family. Doing so requires the ability to analyze our society outside the boundaries of our class belonging. Electricity will return to most of the Lebanese writers and readers who find themselves reading this publication, but it won’t return to large sections of the country’s population. This is a critical aspect of the current crisis, and it is persistently obscured by the quantitative approach and its conclusion that “the Lebanese” as a people suffer from a general decline in their quality of life.

Firstly, the current collapse does not impact everyone in the same way, despite the political use of generalizations like “the Lebanese” or “we.” It is a crisis that strikes at the core of class difference.

Secondly, and more importantly, the crisis does not only deepen the economic differences between the classes; it also widens the significance of these differences, and touches aspects of life that were once outside the bounds of these differences. In the past, there were certain “compensatory institutions,” such as the public-education sector, the Ministry of Health, the public electricity company, and other such institutions, that secured a minimum standard of living in our society. Today we are on the threshold of a rupture that

–Divides our society electrically between those whose lives are rooted in the electrical network and those who have exited this world.

–Divides our society biologically between those who have access to food and medical care and those who are excluded from both, creating a class rift between those who live and those who die.

–Divides our society between those who travel abroad via airplane and those whose journey to seek asylum in Europe ends on “death boats.” These extremes represent divergent relationships to the outside world.

–Divides our society hydrologically between those who can shower and those who see water as a possible carrier of cholera.

–Divides our society educationally between the few in private institutions and the majority who are stuck in public institutions that are falling apart. Still others are altogether outside the education system.

–Divides our society between those who celebrate the birth of a new baby and those who search for an orphanage that can feed their new baby.

I could mention several more examples, but the bottom line is that class difference is no longer simply an “economic” difference. Perhaps what we are witnessing is the emergence of two societies that differ from each other in every aspect of life and death. This is what the word “we” covers up, this “we” that has been historically marshaled against sectarian divisions and strife. This “we” collapses today because of the deepening of class divides.

Structure: Food as a Component in the Social Reproduction of Life

A Crisis in the Social Reproduction of Life

We dislike classes because they disturb our “unifying” view of Lebanese society. This view, like the dominant Lebanese narrative, is not only the prerogative of the regime and its class interests but was also deepened by the “revolution” in its unifying view of a revolutionary people—a view that overlooks class distinctions. “We” dislike any mention of class, just as “we” dislike discussions about capitalism as an economic system. Rather, the dominant class prefers to think of capital as a “mere” economic system that does not affect our social identity, i.e., a system of market and labor relations only, as if capitalism is a system that starts in the morning at seven o’clock and ends at five o’clock in the evening. According to this fantasy, people leave the capitalist system to return to their other society, where they can be whoever they want.

Mammals feeding

But if the labor force produces value through relations in the labor market, as Marx said, then how is the labor force itself produced and reproduced? This is the question asked by the theorists of social reproduction. Put differently, if the theory of capitalism presents an account of what happens between seven in the morning and five in the evening, then the theory of social reproduction, as Marxist and feminist theorist Titi Bhattacharya argues, is an account of what happens before and after these hours. Workers under capitalism need to renew their labor power in order to sell it on the labor market, and this is what takes place outside the realm of the formal economy. The workforce needs food, shelter, care, and rest, and it receives this in the private sphere of the family. The workforce also needs health care, elder care, education, clean water, public spaces, electricity, and other benefits usually provided by the public sector. In addition, the working class must reproduce its members by generating new workers or by “importing” them, either forcibly as was the case in previous epochs, or voluntarily through immigration. The capitalist system needs a productive labor force, and what is called “society” is the domain of this process.

The theory of “social reproduction” attempts to link the process of producing commodities and value, which takes place in the market, with the process of producing life. Just as the economic system has historically taken different forms, systems of life-reproduction also differ between those inherently dependent on the family and those in which the public sector plays an important role. The relationship between the economic system and the system of life-reproduction is a relationship of necessity, but it is also a relationship of contradiction. Capitalism, in its relentless pursuit of accumulation, seeks to transform the reproduction of life into a field of profit and accumulation by commodifying some of its aspects, or by striving to reduce the cost of reproduction. Economic crises are not only crises in the market—that is, crises brought about by an imbalance between supply and demand, or by a decline in asset values. Crises also occur as a result of the contradictory relationship between the market and modes of life-reproduction. Economic crises often end with a restructuring of this system, as happened with economic crises in recent decades, most of which ended with a restructuring in favor of capital.

The Lebanese Mode of Managing Life

Let us return to our distressed food and kitchen. Our food crisis can be seen as a nutritional crisis affecting the possibility of reproducing life in our society, or at least in a form we recognize. Much has been written about the repercussions of the current crisis on Lebanese society, under the rubric of what the media calls the “living crisis.” But our understanding of these repercussions remains embroiled in a quantitative approach to the crisis, with its theories of shortage and scarcity. In reality, what is happening goes deeper than mere shortages of certain goods or a difficulty in acquiring certain commodities, or even the interruption of basic services such as health care and electricity for more and more people. What is taking place is a harsh rearrangement of the process of reproducing life in Lebanon: how people are produced, taken care of, and then reproduced.

When we think of the Lebanese political system, the dominant image is one of violence. Our system is a civil war system. Its history is constituted by massacres, bombings, and corpses. Its main representatives are merchants of violence, from the heads of militias to the dispatchers of car bombs and the owners of silencers. Its structure of rule is based on militias that control and monopolize armed violence. Its discourse glorifies weapons and force. The only state institutions left are those that specialize in oppression. Society has become subject to the rule of violence.

The Lebanese system manages its affairs through violence and death. In accordance with this view, life is managed outside the system, in the private sphere, in the family, or through immigration. We like to believe that our lives “as Lebanese” lie outside this system that we abhor. When we notice the intersection between the system and the management of life, we call it corruption. We mean this in the political sense (interventions that secure the life needs of political supporters). But the actual meaning of corruption is moral, in the sense that we do not want to admit that our lives are intertwined with the system in ways that cannot be untangled.

Most of the vital areas for managing life in Lebanon are outside the scope of the public sector, especially with its current state of collapse. This does not mean that they have nothing to do with the system. Whether it be the family, the private sector, or other institutions entrusted with the reproduction of life, they are all in a necessary but contradictory relationship to the market. More importantly, they evolved in relation to capitalist exigencies. Today, they are transforming under pressure from trends old and new:

Firstly, ever since certain government subsidies ceased, there has been a tendency towards the commodification of good and services. These include electricity and water, which were mainly provided by the state, as well as gasoline, medicine, flour, and other commodities subsidized by the state. (By “state” I mean society itself, since the money comes from the public.) These resources for the reproduction of life have become commodities that are bought and sold on official or unofficial markets. The end of this path is the complete official commodification of these goods. They will be subject to market dynamics when the state legitimizes this commodification process. (Here “state” refers to the legal institution that reflects the interests of the ruling class.)

Secondly, the privatization of certain tasks and functions related to the reproduction of life is an old tendency that is undergoing a revival 1) in the family, from childbearing to caring for children and for the elderly, to providing a degree of social protection; and 2) in social institutions such as associations, parties, and religious and humanitarian institutions, which are assuming responsibility for caring for the poorest, the sickest, and the most needy. The complete collapse of public institutions has placed health care, education, and other means for reproducing life in the hands of private institutions whose services are not sufficient to meet those life needs.

Thirdly, changes in the management of life have produced a shift in the relationship between Lebanese people and the outside world. In the past, this relationship was based on remittances from the expatriate Lebanese labor force (which itself was produced in Lebanon). This paved the way for the importing of cheaper labor.11

With the collapse of the Lebanese currency—and with it, living standards—the features of a new policy began to emerge. This policy exports the management of life, via an increased reliance on humanitarian aid from international organizations to secure the minimum necessities of life.

The Question of Structure

With the collapse of the system that reproduces life, a void has appeared in our political discourse. The duality of the market and the state, or the private sector and the public sector, has unraveled. Attempts to separate politics from the economy, or even to link the two through discourses of corruption and governance, have disintegrated. How do we rethink our predicament from a standpoint that focuses on, and emerges from, the problem of reproducing life? How do we repair what was ruptured by the liberal ideology of the Lebanese system?

INTERRUPTION

Society 1507

Some may conclude that nothing is new in this crisis except the deepening of a certain structural tendency in the Lebanese system, namely a tendency to depend on the market for the reproduction of life.

But there is a key difference from the time before 2019, with consequences that we have not yet fully apprehended. The previous currency exchange rate was not simply a financial indicator but constituted a key material condition for the reproduction of life and its overall management. We can call Lebanese society under these conditions “Society 1507.” The process of reproducing life prior to the current financial collapse was basically subsidized through a rentier system, at the rate of 1507 Lebanese pounds to one US dollar, which enabled this form of life to maintain itself by lowering its cost (and making future generations bear its burden).

If we return to the process of reproducing life before 2019, we find that all Lebanese institutions rested on this currency exchange rate. For example, the kafala system would not have been possible without a currency exchange rate that made it cheap to own the lives of other people. Likewise, systems of private care, whether in education or health, were accessible to large sectors of the population because they were subsidized by the currency exchange rate. At the same time, imported goods, which are vital for the reproduction of life—from petrol to flour—were also primarily subsidized through the currency exchange rate.

Identifying Society 1507 as the foundation for the reproduction of Lebanese life allows us to break free from the binary of public and private—from the binary of those who fulfilled their needs through the private realm and those who depended on public services. The truth that has become apparent now is that we were all dependent on this system, irrespective of our class or our means of reproducing our lives. Regardless of how much we would like to morally expel Society 1507 from our private spaces, we returned to it daily through every payment we made.

The previous system was not egalitarian. The secret of its persistence was its ability to internally subsidize the process of reproducing life. This subsidy was the cost that the system acceded to in order to accumulate wealth. Inequality was not the only problem. With the collapse of this system, it has become clear that our society is unable to provide the bare minimum for the reproduction of life, if not for staying alive.

Materiality: Food, Viruses, and Infrastructure

There is no modern family beyond refrigeration technology, and there is no typical Lebanese family beyond Society 1507. In a less direct manner of speaking, the “family” is historically contingent on changes that occur in society. I don’t mean to simply point out that even our most intimate familial relationships are shaped by social structures, or that that the “family” is affected by material conditions. What I mean is that the coldness of the fridge and the warmth of the family depend on this “materiality,” on our basic existence as creatures, which we try hard to ignore because it constitutes a narcissistic wound to the image of ourselves as rational individuals with sovereignty over our lives and choices.

Starting a few years ago, we had to confront ourselves as material beings. It began with the garbage crisis in Lebanon. The company responsible for managing our garbage was no longer able to control the dumps entrusted with keeping it out of sight. Rubbish accumulated on city streets, exposing the corrupt and deteriorating social structures responsible for managing waste. We tried to contain the scandal by returning the garbage to its rightful place, that is, out of sight. But we refused to learn the lesson that we are just part of a larger configuration.

We persisted in ignoring our marginalized position until a little virus came to paralyze the planet and confine us to our homes. With the virus, we each had to face the materiality of our existence, as biological beings, carriers of a virus against our will. Despite our objections, the pandemic succeeded in demonstrating our marginality to us. Then came the vaccine; with it, we reasserted our sovereignty over life. But for those of us who live here in Lebanon, in the land of cholera, this return is no longer possible. No matter where we look, we find ourselves within “configurations” that conflate the natural with the artificial, turning man into mere matter. Some of these configurations become evident only in crisis, such as:

—The cholera crisis: cholera bacteria—refugee camps—government asylum policies and the racism of the Lebanese state—deteriorating water infrastructure—population density in cities.

—The electricity crisis: the Lebanese financial crisis—the war in Ukraine—crumbling supply infrastructure—pollution—cancer—smuggler networks.

—The food crisis: the financial crisis—export and import policies—a history of soil degradation—irrigation infrastructure—the electricity crisis—the food market—global warming.

These specific crises (and not “crisis” as an abstract concept) have made manifest the social structures that manage every aspect of our live. These crises also have an epistemological dimension: social structures do not appear to the public except at the moment they collapse.

There is no ready answer to the question of what kind of new politics could accord with our present reality. But what is required is not frantic questioning but rather curiosity, the curiosity of a society open to radical change. As the feminist writer Sara Ahmed writes in her book The Cultural Politics of Emotion, “To see the world as if for the first time is to notice that which is there, is made, has arrived, or is extraordinary. Wonder is about learning to see the world as something that does not have to be, and as something that came to be, over time, and with work.”12

Perhaps what is needed today is curiosity about this new reality that is still searching for its vocabulary.

“Lebanon: Children Facing Crisis Hunger Levels to Rise by 14% in 2023 Unless Urgent Action Taken,” Save the Children, January 23, 2023 →.

“Lebanon: Rising Poverty, Hunger Amid Economic Crisis,” Human Rights Watch, December 12, 2022 →.

“Help Lebanon Rebuild and Recover,” UN World Food Program USA →.

Wendell Steavenson, “In Lebanon, Parents Are Abandoning Their Children in Orphanages,” The Economist, January 31, 2023 →.

For Lebanon with a Story, see → (in Arabic).

In a similar vein, the other main TV station in Lebanon, MTV, launched the program Saru miyye (Turning One Hundred) to commemorate a hundred years since the state’s inception and also celebrate our so-called national cuisine.

Camellia Hussein, “A Daily Celebration of Life: What Do You Know about Food Tourism in Lebanon?” Al-Jazeera, August 16, 2019 → (in Arabic).

Sidney W. Mintz, Sweetness and Power: The Place of Sugar in Modern History (Penguin, 1986), 13.

We can think here of modernity as affecting the senses and not only ideas. The historical transformation commonly referred to as modernity is not only meaningful at the level of thought, as some of our Arab theorists of modernity like to say, but also at the level of a transformation in diets. Modernity entails a movement away from a mono-crop diet to a more diverse one, where animal products take up a bigger share of the average diet.

Modernity is often explained through technological advances like the introduction of the radio or TV. The focus on these forms of technology betrays a certain understanding of technology as a vehicle for words—for discourse. But these technologies also included the fridge, which transformed, in a nondiscursive manner, not only our food but also our habits, social structure, taste, and sensitivity to the meanings of food.

The importing of cheap labor did not only serve the market. It was also essential for the management of life: thousands of foreign laborers were assigned the responsibility of caring for children and the elderly, which permitted “the family” to persist in its recognized form. In the same way that there is no Lebanese family today without a fridge, there is no Lebanese family without the kafala (sponsorship) system.

Sara Ahmed, The Cultural Politics of Emotion (Edinburg University Press, 2014), 179–80.

Originally published on megaphone.news in Arabic and translated by Rana Issa.