Only the living can visit the dead, not the other way around. We’re there when George Washington buys a slave. We’re there when a tree bears strange fruit. We’re there in the gas chambers, or when Winston Churchill starves to death millions of Indians. And as we in the present are in the past, we are also haunted by those in the future, those not yet born.

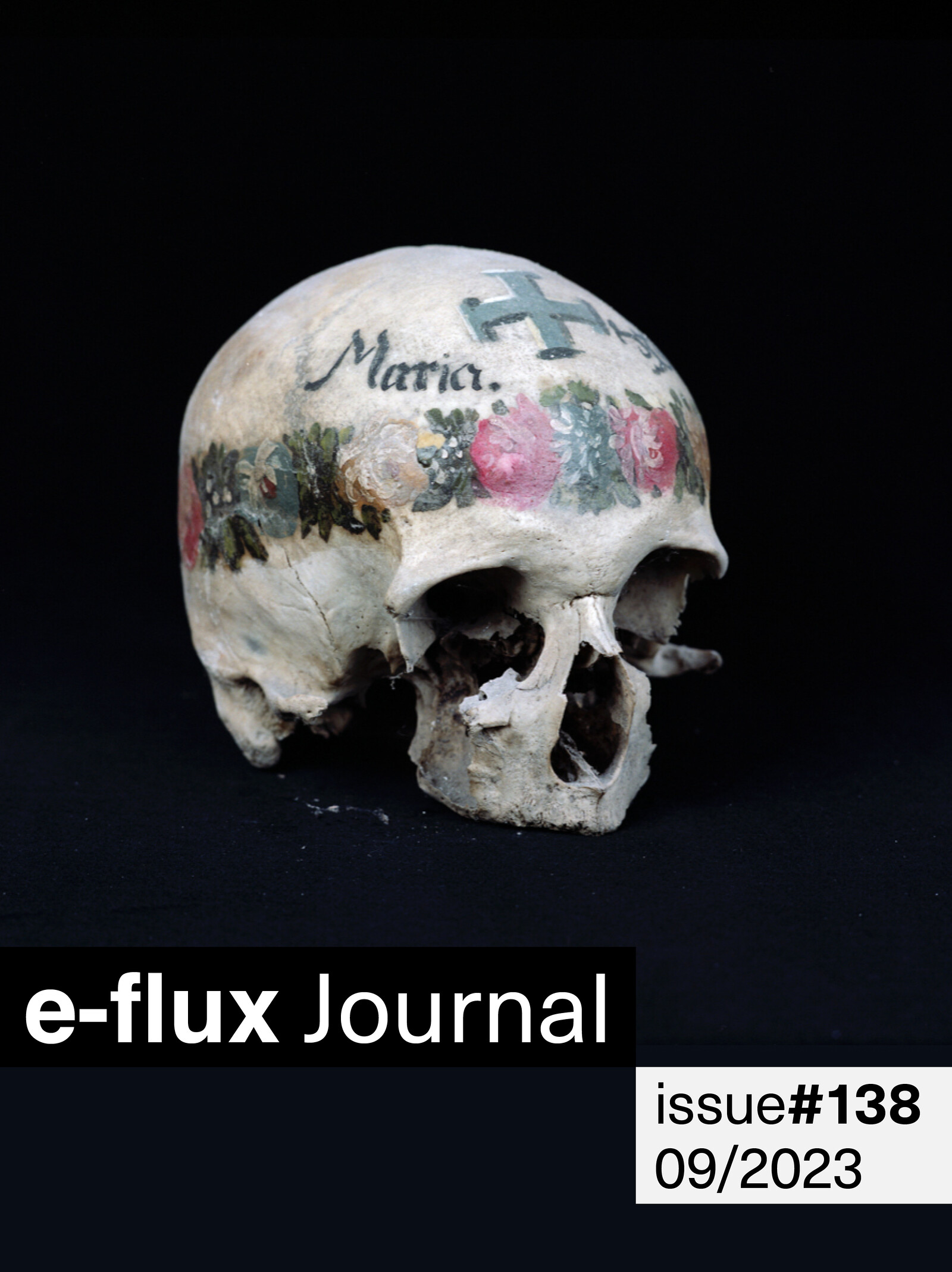

Painted skull from an ossuary in Hallstatt, Austria. Photo: Paul Kranzler, Maria I from the series “Vademecum,” 2013.

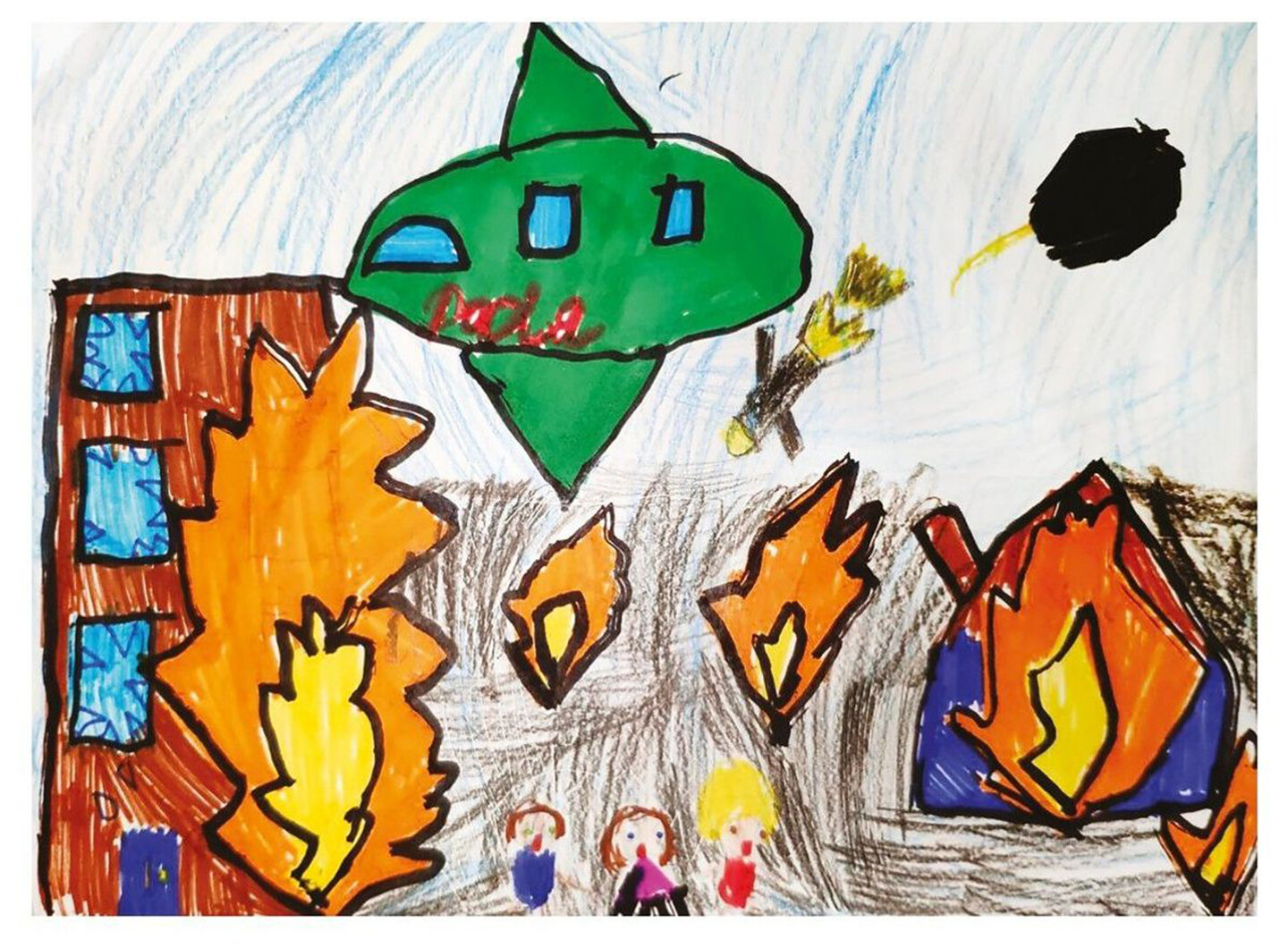

In this issue, Charles Mudede proposes that Octavia Butler brought us a viable theory of quantum movement. Who is capable of moving through time to haunt other people in other places and other times, and in which direction? Paradoxically—and there are many paradoxes—just as the hurt have been hurt, the dead can only be dead, and are for that reason no longer able to move forward in time to haunt us. We, however, are alive in our own time, and we feel pain on their behalf. It is we who reach out from the future—our present—to haunt them in the past. We are in fact the zombies of the already dead, mirrors of our own regrets, just as we are presently haunted by messengers from a future time warning us to not repeat what they know will not end well.

Mariah wants “victory over the sun”; she wants to control her own lighting and thereby create her own system of time. None of this externally dictated, default reality! MC proposes a life of reparative denialism; rather than being touched by the tedium of reality, she floats above it—like a butterfly, that airborne creature of metamorphosis, transience, and flight that has accompanied her image for decades.

Starting a few years ago, we had to confront ourselves as material beings. It began with the garbage crisis in Lebanon. The company responsible for managing our garbage was no longer able to control the dumps entrusted with keeping it out of sight. Rubbish accumulated on city streets, exposing the corrupt and deteriorating social structures responsible for managing waste. We tried to contain the scandal by returning the garbage to its rightful place, that is, out of sight. But we refused to learn the lesson that we are just part of a larger configuration.

While predominantly known for her writing on feminist topics including care, sisterhood, breaking the silence, and sexual ethics, a lesser-known aspect of Lorde’s writing—which shows up in New York Head Shop and Museum—concerns Black spirituality, especially orishas that Lorde turns to while looking beyond empire from within its crumbling constraints.

When I entered the studio, it was messy. Everything was carelessly placed on the table, like underwear and everything. And once I beheld those things, there was some kind of beauty as I looked more closely. Even if someone else could not envision it, I saw beauty while looking at this messy table.

As “collective projects” and “collective agency” take on new and complex forms, how can processes of collective self-identification be grasped—not just historically, but also for the social media–driven present? How can such processes be intervened in and shaped? What is the role of disidentification between various “peoples” who cast each other in the role of other, alien, enemy? Are divergences always motivated through negation, by opposition?