In 1973, Peruvian art critic Juan Acha called on his Latin American colleagues to overcome the so-called desarrollista (developmentalist) aesthetic and forge another that “includes both our solicitations and practices whose artistic nature is today recognized, as well as our other desires and sensitive acts of which we are not aware and which are not considered as art.”1 At the end of that decade, Acha published the first volume of his theoretical project Arte y sociedad: Latinoamérica (Art and society: Latin America), in which he advanced that new aesthetic. At the same time, in several meetings during the 1970s in Quito, Austin, Mexico City, Sao Paulo, and Caracas, different Latin American critics advanced the need to elaborate a theory of their own. The 1981 Primer Coloquio Latinoamericano sobre Arte No-objetual y Arte urbano (First Latin American Colloquium on Non-Objectual Art and Urban Art), organized by Acha in Medellín, was perhaps the culminating moment of this process, opening a route for the theorization of Latin American culture amidst the Cold War, the triumph of the Cuban Revolution, and the emergence of popular movements against military dictatorships throughout the region.

This intellectual network brought together diverse positions that have mostly disappeared from cultural criticism written in recent decades. Critics such as Acha, Jorge Romero Brest, Damián Bayón, and Marta Traba proposed “a utopian project: to find a defined cultural identity for Latin America,” since they believed that the greatest problem of art in the region was cultural dependence, which they explained on the basis of Dependency Theory.2 This theory argued that the region suffered from a lack of identity and integration, engendered by its dependence on the First World. This dependence deprived Latin American art of a recognizable unity outside the mirror of its dominators. It was argued that this dependentist Latin Americanism held firm until the 1980s, when new critics like Gerardo Mosquera, Nelly Richard, Luis Camnitzer, and Mari Carmen Ramírez entered the scene.3 This “new criticism,” as it was called, proposed a Latin Americanism of difference in a postmodern and “anti-utopian” tone that appealed to the irreducibility of artistic practices in each cultural context.4

Juan Acha addressing the audience at the First Latin American Colloquium on Non-Objectual Art and Urban Art, Museo de Arte Moderno de Medellín, Colombia, May 1981. Photo: Lourdes Grobet.

Another critical project was proposed by Mexican art historian Rita Eder and Peruvian critic Mirko Lauer in the early 1980s, which they called Teoría Social del Arte (Social Theory of Art, STA). In this text, I present STA as an alternative to the Latin Americanisms of both dependency and difference, to the extent that these views framed the debate in terms of identity, in its historical lack or in a postmodern celebration of hybridity. Instead, STA sought to understand the different forms of the plastic (not only art but also craft and design) in their socioeconomic and ideological determinations, instead of prolonging the obsession with Latin American identity that has run through the region’s intellectual history from the nineteenth century to the present.

An Annotated Bibliography

Eder and Lauer burst onto the scene of Latin American criticism in the mid-1970s at the meetings of international critics mentioned above. In 1976, the latter published his Introducción a la pintura peruana del siglo XX (Introduction to twentieth-century Peruvian painting), a Marxist reading of art history which sees painting as a “closed dialogue within the dominant culture.”5 This approach was unprecedented in the local sphere, at least since the times of José Carlos Mariátegui, the father of Peruvian and Latin American Marxism in the 1920s. Eder proposed a critique of the three dominant positions in cultural criticism: Marta Traba’s quest to oppose the neo-avant-garde with an “art of resistance” that appealed to the cultural roots of each Latin American country; Frederico Morais’s radical avant-gardism; and finally Ferreira Gullar’s proposal to dialectically overcome the two previous positions through a reflection on avant-garde art in underdeveloped countries.6 Each position was founded on a diagnosis of national realities based on the premises of Dependency Theory. Thus, Eder and Lauer entered the critical scene with a proposal of theoretical and methodological renovation anchored in Marxism. Both had links with Acha, who had settled in Mexico City in the early 1970s and injected into cultural debates his interest in “sociological criteria.” This involved working from the perspective of (a critique of) political economy to study the impact of processes of production, distribution, and consumption on any social phenomena. Although militancy did not define these critics, STA is inseparable from the revolutionary cycle opened in Cuba in 1959 and the broad legitimacy that Marxism gained in the region between the 1960s and 1980s.

Mirko Lauer, Crítica de la artesanía, 1982.

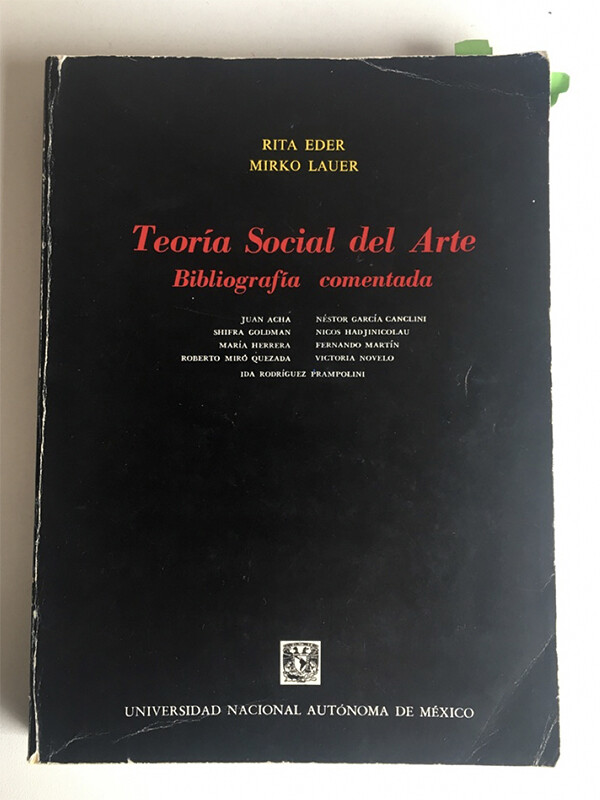

In 1980, Eder and Lauer proposed a project to the Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas (Institute of Aesthetic Reasearch, UNAM, Mexico): they would carry out extensive bibliographic research to explore STA and elaborate an annotated bibliography. They were interested in gathering “all those methodological tendencies that give a privileged place to the sociohistorical aspects of plastic creation.”7 After collecting a thousand texts with the help of computers at the Center for Scientific and Humanistic Information (UNAM), they gathered Acha, Shifra Goldman, María Herrera, Roberto Miró Quesada, Néstor García Canclini, Nicos Hadjinicolaou, Fernando Martín, Victoria Novelo, and Ida Rodríguez Prampolini to write reviews of the most significant texts, resulting in 242 entries that constitute the bulk of the volume Teoría Social del Arte: Bibliografía Comentada (Social theory of art: An annotated bibliography), published in 1986.

The reviews brought together commentaries on texts of diverse origins (France, the United States, Mexico, Spain, Germany) and languages (English, Spanish, French, German, Italian, Czech). Some thinkers, such as Pierre Bourdieu, loom large in the bibliography, with major contributions to the fields of the sociology of art, Marxist aesthetics, the social history of art, and semiotics. With some bitterness, the editors noted the paucity of Latin American thinkers, and Third World thinkers in general, in the field of STA, which is why they made an effort to incorporate more texts than the computers identified alone. Thus, the book presents a body of work that, according to the editors, advances towards a “process of unification” to create a new STA.8 But what exactly did they mean by this?

Eder and Lauer wanted to unify Marxist social art history, the sociology of art (functionalist and structuralist), and the contributions of Latin American criticism from the previous decades. It might seem, then, that something like an STA already existed, and the editors simply named it. However, they argued that it was a new project, linked to previous Latin Americanist intellectual movements but substantially different. In their “Preliminary Study,” Eder and Lauer trace how the “social gaze” has viewed the plastic from the aftermath of the French Revolution to the present. They periodize the trajectory of this view from the political radicalism of 1789 to the utopian socialists, and then show how Marxism, between 1870 and 1917, broke from the view, marking a double turn. On the one hand, it proposed a materialist vision of the plastic as an aspect of social life. On the other, it led to the development of a theory of culture in which art is included in the construction of socialism. Despite this historical break, argue Eder and Lauer, aesthetic reflection in Marxism has been reduced to socially contextualizing idealist aesthetic discourse without questioning its central categories (taste, beauty, sensibility, etc.). In this form of Marxism, each social class has its own sensibility, and the socialist state has the task of promoting a proletarian aesthetic, defined a priori on the basis of abstract criteria. Eder and Lauer conclude that Marxist aesthetics wastes the epistemological and critical potential that historical materialism could bring to the knowledge of the plastic.

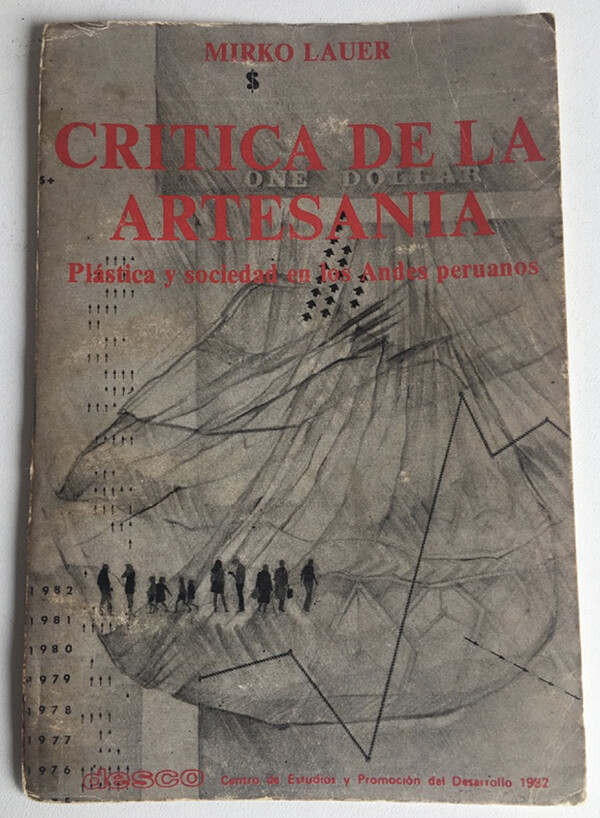

Luis Camnitzer, This Is a Mirror, You Are a Written Sentence, 1968.

At the same time, in their view, the 1920s and ’30s produced a complex series of perspectives on the plastic due to the growth of the art market worldwide and the emergence of “nationalist theorizations about the art of underdeveloped countries.” Hence, “the theoretical elaboration of the twentieth century can no longer be done, as in the previous century, in relation to a ‘unique’ and simple artistic system.” The social gaze can no longer treat art as a universal category, and “the profound meaning of [art’s] variety (its historical specificity) begins to be explored.”9 The changes of the 1920s and ’30s also affected the traditional disciplinary distribution of studies of the plastic:

Art history loses its “universal” nature and is confined—not only by the subject matter, but also by the method—to being a history of the European system of artistic production and its origins, without the capacity to understand the developments of that system toward the periphery of capitalism. Criticism, which moves to the journalistic sphere in order to keep pace with production and innovation in a plastic-arts sphere that has generalized the dynamics of avant-gardism, loses its capacity to grasp panoramas and is confined to the particular. Art theory returns to its traditional options: to be a philosophy of nominal abstractions or to be a classification of empirical realities in representation.10

It is nothing new to claim that in the twentieth century, art history lost its assumed universality. Nor is it new to say that art criticism usually deals with the particular, without relying on any major theoretical framework. What is crucial in Eder and Lauer’s contribution, however, is the disjunction between generalist elaborations, as in traditional aesthetics, and the examination of the empirical, where the concrete particularity of the plastic is grasped. This contrast structures another opposition that organizes a good part of Eder and Lauer account, namely, the opposition between representation and the material support of the plastic object. These terms were developed by Lauer in his 1982 Crítica de la artesanía (Critique of craft), and here they organize the elaboration of a new social gaze that needs to reframe representation (the image) as only one aspect of plastic objects (be they artistic, artisanal, or design). This aspect must be complemented by an analysis of the physical support of objects and the social relations that give them a specific form.11 Note that the object to be investigated here is no longer Latin American identity or cultural dependence, but the socioeconomic and ideological determinations of the plastic object. The premises have changed.

What kind of understanding of Marxism underlies all of the above? The reconstruction of the history of how the social gaze regarded the plastic incorporates historical revolutions, the emergence of various ideologies, and capitalist expansion since the nineteenth century to examine not art or the artistic field, but the ways that the plastic is an aspect of the historical process. This is the main premise of STA: it is not that plastic objects have a “social” and a “nonsocial” (or aesthetic) function, but that they are an aspect of social relations. Consequently, studying them requires conceptual innovations—in line with Walter Benjamin’s view—that allow us to “reopen the plastic object and contemplate the complex mechanisms of its internal structure and its relations with society.”12 Reopening an epistemologically closed object: traditional aesthetics and art history see art only as image or representation; sociology sees it only as an object that circulates in social relations. Faced with these one-dimensional views, STA sought an understanding of the plastic object in its two facets, as both material object and representation. It was therefore necessary to gather the contributions of existing perspectives, but also to propose a different horizon.

Art as a Historical Category

Eder and Lauer take a stand against a view that had dominated Marxist aesthetics, one that considered art “as an already constituted historical category” and reduced materialist analysis to interpreting representations.13 Based on fragments of writing by Marx and Engels about the art and literature of their time, and especially on Marx’s 1844 manuscripts, this contenidist vision (centering the opposition between form and content) was, according to Eder and Lauer, shared by Marxist aesthetic theorists and socialist state officials. At the same time, this orthodox vision remained within the limits of idealist aesthetics, since its only concern was inverting its categories—taste, beauty, art, aesthetics, etc.—to give them a social character. Hence Lauer speaks of a “crust” of idealist categories that prevent Marxist aesthetics from thinking about the plastic from a truly materialist (social, historical) angle.14

In opposition to this state of affairs, Eder and Lauer move instead towards “the conception of artistic work as an articulated process whose elements have differentiated relations with various aspects of the social.”15 In order to explore the “labor (production) character” of the plastic, it is necessary to recognize: 1) “the character of the plastic creator as a worker (producer), within a critique of the bourgeois separation between manual and intellectual work”; 2) “the artistic as a process that takes shape in its social reproduction and not only in the materiality of the finished work”; and 3) the fact that “the relations between the social and representations are conditioned by the way the artistic production process as a whole is inserted within the structure of the relations of production.”16

In contrast to orthodox Marxist aesthetics, Eder and Lauer aim for “the disarticulation of the established idea of the plastic object (the socially recognized unity between representation and material support), differentiating instead between the physical idea of the artistic work and that of its materiality.”17 Far from a mechanical materialism, here “materiality” alludes to the social relations that are typically obscured by the traditional emphasis on representation. The reopening of the plastic object would allow, finally, the articulation of both dimensions, the material and the representational.

The idea was not to take Marxism as an aesthetic doctrine or a framework for organizing the “correct” sensibility of the avant-garde, but rather to assume it as a method for analyzing the plastic object as a part of wider social dynamics. The choice of the notion of “the plastic” also indicates the distance Eder and Lauer took from the category of art as such. This distance was posed in another way by Acha in 1979 in his writings on the “system of cultural production,” which he understood as the combination of craft, art, and design, just as Néstor García Canclini proposed the notion of “symbolic production.”18 These perspectives sought a terrain of analytic neutrality from which to make visible the social process by which objects are produced and classified under different categories, and to discuss the supposed universality of art as the dominant cultural category. But sharing the ground of “sociological criteria” did not mean that they understood this notion in the same way.

Rita Eder and Mirko Lauer, Teoría social del arte, 1986.

Eder and Lauer confronted the problem of aesthetic or cultural categories in a peculiar way. According to their view, if aesthetics (Marxist or not) and art history have taken the notion of the artistic as something given, it was necessary to follow Italian philosopher Mario Perniola’s suggestion to carry out a “critique of art as a historical category.”19 This category emerged during the Renaissance and was consolidated in its modern form during the nineteenth century in Europe, acquiring a metaphysical form that produces and maintains the appearance of operating in a sphere separate from and irreducible to the social. This is the bourgeois ideology of art that organizes the art institution. Note that assuming the historicity of the category of art also implies breaking with a entrenched aesthetic tradition, erroneously extended in Marxist aesthetic theory, that sees art or the aesthetic as a primary reality of the human, an anthropological constant of a “millenarian” character that appears after liberating itself from the direct utility of objects.20

By contrast, in STA “it would be necessary to arrive” at a “radical critique of the historical category,” especially in a region like Latin America where the coexistence of “diverse historical categories originating from the plastic” is palpable.21 In other words, understanding the historicity of art as a social category allows for a better understanding of the trajectory of other forms of the plastic (craft, design, etc.). The Latin American context added density to Perniola’s proposal, since the imposition of the category of art during the colonial process made evident its historical character, introduced in lands and societies where nothing similar operated before the Conquest. Thus, STA reintroduced a concern for “the constitution of the artistic category in Latin America,” but no longer in Latin Americanist terms:

The very concept of art was not originally defined among us [in Latin America] by differentiation from scientific activities, but by differentiation with respect to the plastic of dominated sectors and cultures. An important fact in this particular constitution of the artistic is that it is not based on the disappearance of the pre-artistic (artisanal) in history, as happened in Europe, but on a differentiation-articulation with the artisanal.22

Lauer adds that “the extirpators of idolatries who pursue the representations of the cult of ancient religiosity initiate, by violent and catechistic means, the division that will later become that other art/nonart.” Thus, the ideology of art is assumed by “the enlightened sector of Colonial domination that will later form the embryos of local bourgeoisies in each independent Republic.”23 That is why “the painting of our nineteenth century is, to a large extent, an attribute of the dominant groups, which develops when they are already in power with the Republic, and which does not have rebellion among the repertoire of its representations. [A] consecration, now secular, of the established order.”24

For STA, then, cultural conflict and class struggle are the unavoidable frameworks for examining the relations that the categories of art and craft (or the artisanal) have sustained in the region. Based on this, it is possible to reconstruct the historical constitution of these categories and the social frontiers they configured, to illuminate the diverse forms of the plastic, from the colonial period to the present. It is clear that we are no longer in the universe of the problem of identity. Instead, this is an understanding of Latin America as a product of class struggle in the Third World. Very little is left of the Latin Americanism of dependency here. There is also little left of avant-gardism and its intransigent repudiation, which generated no small amount of drama among Latin American critics of the 1960s and ’70s.

As a code name for a Marxist theory of the plastic (as I would prefer to call it), STA did not aim at sustaining the figure of the art critic as a provocateur of avant-gardism. The objective was more precise: to renew the theoretical and methodological apparatuses that produce knowledge of the plastic, which would ensure the apprehension of its different forms of social existence. All this, finally, pointed to a greater problematic:

In the “crisis of the universal” that is evident today, the social theory of art must be able to give a theoretically coherent account of the historical particular, that is, to explain the diversity of the plastic not on the basis of a simple observation of difference, but by virtue of a sociohistorical articulation of the parts. Today we lack this theory of articulation, and it is from it that the plastic process can be reconstructed in knowledge as one of the aspects of the general constitution of the social.25

Far from adding to this “crisis of the universal” (the rise of postmodernism), STA was posed as a theory that accounted for the concrete and specific plastic object by locating it in the historical axes from which it emerges and in the social totality in which it operates. It thus points to a theory of articulation that should be made explicit.

Following Louis Althusser’s revival, in the 1960s, of the debate within European Marxism on modes of production, a discussion was opened in Latin America about how to characterize Latin American social formations in the theoretical scheme outlined by Marx. At stake was an understanding of the transition from feudalism to capitalism in the region (distinguishing feudal elements from industrialization processes, for example), in addition to discussing colonization and independence. The debate in Latin America reached a high level of sophistication thanks to contributions from thinkers like Roger Bartra, who understood that capitalism operated through an articulation of past modes of production, rather than following unilinear paths of development.26 While Dependency Theory saw the region’s subordination to European metropolises as the result of unequal exchange between the Global North and South—a problem specific to the sphere of (global) circulation—Bartra called for an examination of forms of labor, of production, as the proper terrain for understanding Latin America’s place in the global capitalist system. This allowed the study of the articulation of different forms of production under capitalism (including all forms of the plastic as different production systems), which led to further clarification of the persistence of precapitalist economic formations in the region and their peculiar processes of transition from feudalism to capitalism.27

The link between these debates and STA was explicitly highlighted by Lauer in his Crítica de la artesanía. He writes that craft production in societies where class and race are superimposed as criteria of social differentiation raises the problem of articulation—in particular

the articulation of what is ideology with what is a form of production, the articulation of some forms of production with others, the articulation of what is separated by class dividing lines. A vision from the perspective of articulation becomes indispensable in order to approach from the social totality a phenomenon that, like the plastic, has been presented in isolated compartments.28

An analysis of articulation brings together what has been separated by the various fields of knowledge that have dealt with crafts (anthropology, folklore, etc.), while at the same time revealing the social totality in which the plastic unfolds and differentiates itself according to its various categories (art, craft, design). Hence, Eder and Lauer argue that “the problem of a social history of the plastic” must be approached based on

the examination of the constitution, reproduction, and dissolution of historical categories through individual practices embedded in the social. The latter presupposes an empirical knowledge of the plastic system broader than that of the organization of representations and forms, and the recognition of internal (structural) relations between the developments of the elements of the plastic object.29

This “plastic system” that brings together the different categories would be the proper object of an STA that confronts the “crisis of the universal” by studying the articulation of the different forms of the plastic.30

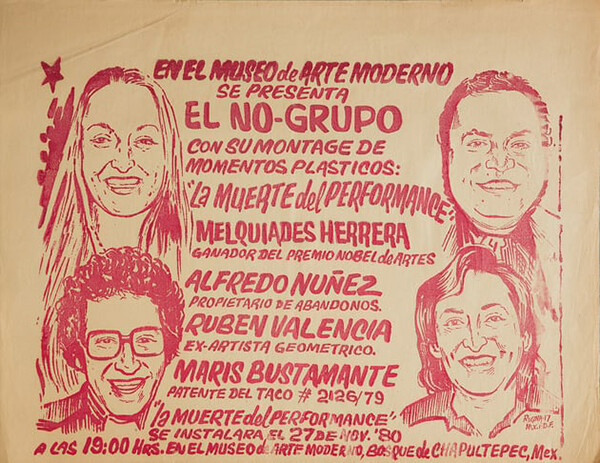

No Grupo poster, offset, 1982. Fondo No Grupo, Centro de Documentación Arkheia, Museo Universitario Arte Contemporáneo, UNAM, Mexico.

Between (and Against) Two Latin Americanisms

Even though the Annotated Bibliography quickly sold out, more recent accounts of the history of Latin American criticism from the 1960s to the 1990s do not register the specificity of STA as a theoretical project, different from the Latin Americanisms of dependence and difference. Fabiana Serviddio notes that the former was seen as a “utopian model of critical judgment” and that “it was constituted as a theoretical alternative in strong competition with the modernist paradigm. The utopia of autonomy of Latin American art underlay many of the positions of art criticism of those years.”31 The critique of political economy incorporated by Eder and Lauer did not advance toward this “utopia of autonomy of Latin American art,” but rather sought to clarify the forms of social existence of the plastic. Moreover, Marxism is hardly in “competition” with the “modernist paradigm” from an external position; it is rather an immanent critique of bourgeois culture. Furthermore, STA did not pave the way for the emergence of the Latin Americanism of difference, as was proposed in the postmodern “new criticism” of the eighties and nineties, which Piñero describes as the principal break with Latin American dependentist critique.32 STA has thus disappeared from canonical accounts of the history of art criticism in Latin America.

Although STA was not formulated as a transition between dependency and difference, the fact is that by 1996, when Gerardo Mosquera published Beyond the Fantastic: Contemporary Art Criticism from Latin America, previous criticism as a whole (dependentist, Third Worldist, Marxist) was seen as the product of an era of feverish utopian thinking that, by the mid-nineties (when the “end of history” was proclaimed), had been replaced by anti-utopian thinking far removed from the pretensions of modernist totality.33 In art criticism, as well as in Latin American cultural studies, a fierce battle was waged against dependentism. At the same time, Marxism was accused of having denied the sociocultural heterogeneity characteristic of Latin American societies, due to its inability to look “beyond” social classes.

The retroactive perspective inaugurated by Mosquera, rooted in the new postmodern Latin Americanism, seems to have prevented the recognition of the STA project on its own terms. Curiously, among the authors that Mosquera includes in Beyond the Fantastic, García Canclini, Lauer, and Brazilian critic Aracy Amaral appear as “bridges” between the old and new times, although they “continue to favor the sociological point of view characteristic of the previous period.”34 Perhaps they were bridges that sought to connect something different than what history ended up putting on the other side, for the STA, while emerging as a critique of the Latin Americanism of dependency, did not turn towards postmodernism.

It is not difficult to explain the disappearance of STA in the midst of the end of the Cold War, the discrediting of Marxism after the defeat of the USSR, and the hegemony of neoliberalism. Postmodernism and nineties-era globalization left behind the Marxist premises that sustained STA. In addition, categories such as “the plastic” aged poorly in the context of global contemporary art, visual culture, and so on. Some of the authors gathered in Annotated Bibliography also adopted new positions in the nineties. For example, García Canclini’s Culturas híbridas (Hybrid cultures), published in 1990, shows a clear departure from the Marxist premises he developed in his early books.35 Perhaps García Canclini does operate as the “bridge” that Mosquera speaks of, as suggested by the former’s embrace of hybridity and deterritorialization in the nineties, which connect the Latin Americanism of dependence and its negation through difference, the new central category of global postmodernity.

Despite its abandonment in the nineties, STA is worth knowing and updating today. It is concerned with understanding the concrete as an essential first step in transformative criticism and cultural praxis. It also invites us to reconsider what historical materialism offers for the critical analysis of the plastic and cultural production in general. Above all, it underscores the urgency of a theory of articulation in understanding the dynamics of art, craft, and design within the contemporary capitalist mode of production.

Juan Acha, “Por una nueva problemática artística en Latinoamérica,” Artes Visuales, no. 1 (1973). Unless otherwise specified, all translations are mine.

Fabiana Serviddio, Arte y crítica en Latinoamérica durante los sesenta (Miño y Dávila, 2012), 244.

Gabriela Piñero, Ruptura y continuidad: crítica de arte desde América Latina (Ediciones Metales Pesados, 2019).

For the characterization of the 1990s as a new postmodern and anti-utopian moment in Latin American art criticism, see Gerardo Mosquera, “Introduction,” in Beyond the Fantastic: Contemporary Art Criticism from Latin America, ed. G. Mosquera (MIT Press, 1996).

Mirko Lauer, Introducción a la pintura peruana del siglo XX (Mosca Azul Editores, 1976).

Rita Eder, “Algunos aspectos de la crítica de arte en América Latina,” Artes visuales, no. 13 (1977).

Rita Eder and Mirko Lauer, Teoría social del arte, bibliografía comentada (UNAM, 1986), 7.

Eder and Lauer, Teoría social del arte, 8.

Eder and Lauer, Teoría social del arte, 31.

Eder and Lauer, Teoría social del arte, 32.

I have analyzed in detail Lauer’s theoretical development between 1976 and 1982 in Mijail Mitrovic, “Passages of a Marxist Critique of Art in Peru: From Artworks to Plastic Objects (1976–1982),” Historical Materialism 31, no. 1 (2023).

Eder and Lauer, Teoría social del arte, 30.

Eder and Lauer, Teoría social del arte, 21.

Mirko Lauer, Crítica de la artesanía: plástica y sociedad en los Andes Peruanos (DESCO, 1982), 48.

Eder and Lauer, Teoría social del arte, 21.

Eder and Lauer, Teoría social del arte, 37.

Eder and Lauer, Teoría social del arte, 21–22.

Juan Acha, Arte y sociedad: Latinoamérica (FCE, 1979); Néstor García Canclini, La producción simbólica: teoría y método en sociología del arte (1979; Siglo XXI, 2010).

Mario Perniola, “El arte como categoría histórica,” Hueso Húmero, no. 11 (October–December 1981).

On this subject, see Acha, Arte y sociedad; Adolfo Sánchez Vásquez, Las ideas estéticas de Marx (Siglo XXI, 2005); and Mijail Mitrovic, “Robinsonadas: Adolfo Sánchez Vásquez, Juan Acha y el problema del arte como categoría histórica,” Antagonismos, no. 3 (2021).

Eder and Lauer, Teoría social del arte, 41–42.

Eder and Lauer, Teoría social del arte, 34.

Lauer, Crítica de la artesanía, 21.

Eder and Lauer, Teoría social del arte, 34. For the authors, the first break in this “established order” comes with Indigenism in the 1920s, where the problem of identity in the region—with its emphasis on a representation of culture that occludes knowledge of its own material supports—is also defined.

Eder and Lauer, Teoría social del arte, 42.

Roger Bartra, “Sobre la articulación de modos de producción en América Latina,” in Modos de producción en América Latina (Delva Editores, 1976).

The circulation that takes handicrafts from the market to the boutique, as García Canclini proposed, was part of these same debates. Néstor García Canclini, Las culturas populares en el capitalismo (Casa de las Américas, 1982). For a theorization of these processes of transition from the perspective of Marxist anthropology, see Maurice Godelier, “Introducción: el análisis de los procesos de transición,” Revista Internacional de Ciencias Sociales, no. 114 (December, 1987).

Lauer, Crítica de la artesanía, 10.

Eder and Lauer, Teoría social del arte, 38.

There is no need to discuss here whether artistic production responds to the determinations of capitalist production in the strict sense. Suffice it to say that the artistic has accompanied capitalist expansion as a fundamental part of bourgeois culture.

Serviddio, Arte y crítica en Latinoamérica, 246.

Piñero, Ruptura y continuidad.

Mosquera, “Introduction,” in Beyond the Fantastic, 12.

Mosquera, “Introduction,” in Beyond the Fantastic, 15.

Néstor García Canclini, Culturas híbridas: estrategias para entrar y salir de la modernidad (Grijalbo, 1990). For an analysis of the transition from Marxism to postmodernism in García Canclini’s work, see Mijail Mitrovic, “La cultura popular en el ‘joven’ Néstor García Canclini: del marxismo gramsciano al posmodernismo progresista (1977–1982),” Antropologías del Sur 9, no. 18 (2022).