Sand has a way of getting into things. Take any day at the beach and the grainy aftermath that persists for days or maybe weeks afterwards, underneath fingernails, in your shoes and socks, in the whorls of your ears. Because sand consists of tiny, similarly sized grains, it invites and overwhelms counting. Holding a single grain in the palm of your hand is a cliché; think of sand for more than a moment and you picture it slithering through the neck of an hourglass, already standing in for something else. Yet despite its symbolic qualities, it is a real and fundamental material for the construction of the built environment of the contemporary world.

Beyond the liminal allure of the landscapes contoured by it and the well-established study of its geomorphological properties, sand has acquired a conspicuous profile in contemporary urbanization over the past two decades. The United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) began drawing attention to the looming possibility of a global sand crisis in 2014.1 Subsequent work by UNEP and multiple NGOs has drawn attention to the significant environmental degradation associated with sand dredging and dam construction across the world. In terms of quantity, the only resource humans consume more of than sand is water.2 Nonmetallic minerals employed primarily in construction, including not only sand but also gravel and crushed rock, are the fastest-growing category of extracted material. Their extraction has increased six-fold in the Asia-Pacific region over the last two decades.3

Singapore, a city-state in Southeast Asia the size of New York City and half the size of London, is the largest per capita importer of sand in the world. The city-state’s urbanization and never-ending construction of housing and infrastructure is partly responsible for its considerable appetite for sand, but this use pales in comparison to the amount it requires for its land reclamation project, which has seen the city-state expand its territory from 585 square kilometers in 1959 to 724 in 2022. Singapore’s construction of territory, and the sand it has imported from all over Southeast Asia to resource its geophysical projection of sovereignty, invites us to consider the implications of urbanization’s enrollment of greater and greater volumes of sediment, and the geopolitics of the global sand crisis.

Sand and sediment are not identical; the former is a subset of the latter. And as a resource, sand exists in a set of fuzzily circumscribed scalar ranges, between silt and gravel, that vary from one standard of measurement to another. To talk of sand in relation to urbanization is to talk of a species of sediment sorted and extracted to be mixed with cement into concrete, or dumped in mind-numbing quantities into seas, rivers, estuaries, and swamps until it surfaces from beneath as smooth and dependable square feet of solid land. Grain size, profile, composition, and chemical purity all factor into what sand can be incorporated into and used for. But before it is sorted and sucked through the pump of a suction dredger or scraped by the bucket of a grab, it is sediment. To think with sediment is to think through states of matter, without the certainty of matter or the sovereignty of the state. As sediment flows and locks into place, it expresses characteristics of all three states of matter, depositing and eroding, refusing singularity, set adrift by water and wind. A geomorphological errantry, sediment is always on the move or on the cusp of peregrination, putting all that it touches in its itinerancy into relation, and also at times irritation. To stay with sediment is to stay with the geology of the planet put into relentless motion by air and water.

In its multiplicity, sand becomes a kind of narrator for those elements, its granular dynamics molding the meanders of rivers, shifting coastlines by infinitesimal degrees day by day, and coagulating around the maws of estuaries. In its modulation of turbulence, force, and velocity, sediment sutures together landscapes that are neither solid nor fluid, but the porous interplay of both categories, capable of grounding and ungrounding through sedimentation, suspension, glaciation, erosion, entrainment, consolidation. Sediment also builds up, accumulating into landscapes of inundation and desiccation, its appearance in dunes, shoals, and piles both excessive and recessive.

This same promiscuous statelessness of matter is also the undoing of sediment. Its granular transitions between phases, expressing characteristics of matter without lingering in any single state unless compelled to, are exactly what makes sediment liable to capture and subversion by the capitalist production of space. Only rough, angular grain profiles are suitable for construction, with concrete requiring regularity and chemical neutrality. Desert sand honed by aeolian processes is too smooth to bind into concrete or consolidate into solid ground. (And, given the extensive role played by deserts such as the Sahara in the formation of global weather patterns, we ought to be relieved that its sand is useless, for now.) Sand’s construction as a low-value, high-volume resource guaranteed the ascendancy of concrete, alongside its flexibility and relatively lower-skill requirement as a construction material, as the omnivorous grey goo of modernity. The geographer Gray Brechin writes that San Francisco, and other cities like it, are “inverted minescapes,” rising high into the sky through the excavated minerals and metals that form the raw material of high-rise sprawl.4 Urbanization here is the gradual exhumation of a planetary body without organs—a surface of noise and fume sitting atop the echoing depths of the hollowed earth.

Yet sediments aren’t dug out of the ground. They are instead sucked and cut from the fluvial and coastal flows they contour. The negative space carved by sand mining isn’t static, so the glistening and final fixity of a skyscraper traces a temporal negation in addition to a spatial one. Every ton of sand cast into concrete or consolidated into solid ground imperceptibly alters the course of rivers, stammers out the coast into unintelligible configurations, and renders meanders traversed by riverine communities unrecognizable. These volumes dredged in staggering quantities for a few dollars a ton are geomorphological archive whose sudden excision, in sufficient quantities, exacts a brutal toll. The water forgets where it went, becomes turbid, its courses unwinding as velocities intensify. As the cheapest and most convenient sand is exhausted, construction companies, governments, and middlemen in the dredging industry scour increasingly remote coasts and river systems for sediment of just the right size. The lucrative black-market trade in sand triggers sediment rushes. Bullish entrepreneurs with the capital to spare buy up ships and equipment to carve a few thousand tons for themselves, with the profits flowing through networks of patronage and elite capture. Black markets of sand are flourishing around the world, from Rio De Janeiro to Lagos to Tamil Nadu.5 Multiple controversies surrounding sand mining in Southeast Asia have stemmed from one small island state’s prodigious thirst for sand: Singapore.

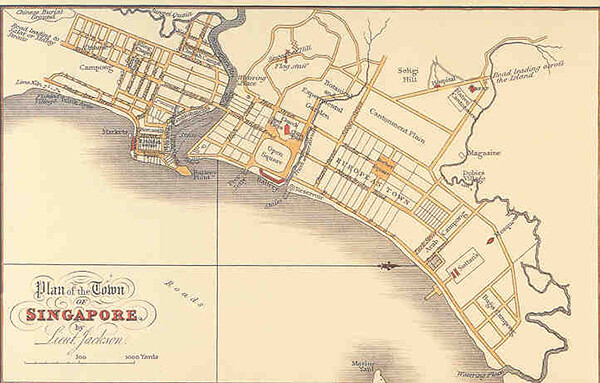

Between 2006 and 2016, Singapore, with a population of less than six million, was the top importer of sand in the world four times. Land reclamation there truly began with colonization by the British East India Company, with Boat Quay in 1822, when three hundred or so convict laborers who were paid pittances chopped down hills and cut up stones to embank a swamp, lest it remain fallow.6 When Singapore became an independent city-state in 1965, reclamation projects initially cut down hills for fill material, flattening the interior and exterior of the main island alike. Sand began to creep onto Singapore’s UNCOMTRADE import ledgers in the nineties, as it began to import sand from Malaysia and Indonesia, its closest neighbors, to resource the construction of territory that would become Jurong Island, Tuas, Changi, Pulau Tekong, Pulau Semakau, and Pasir Panjang, as well as a slew of smaller islands.

Plan of the Town of Singapore by Lieutenant Philip Jackson, who was the engineer and land surveyor tasked with overseeing the physical development of Singapore, 1822. National Museum of Singapore. License: Public Domain.

As these projects grew more expansive and the city-state’s demand for sand intensified, Malaysia and then Indonesia banned sand exports to Singapore (allegedly after Pulau Nipah, an island which formed their maritime boundary with Singapore, was dredged so intensely it sank beneath the waterline at high tide). This prompted spiraling costs. Sand that was bought for $5 a metric ton swelled to $300 a metric ton in 2003, before stabilizing at about $30 a metric ton.7 This price spike shook the city-state to its core, prompting the opening of a series of construction sand stockpiles maintained by the Housing Development Board, the government statutory board with the most expertise in land reclamation. The government began purchasing sand through its web of contractors and subcontractors from Vietnam, Cambodia, the Philippines, and Myanmar. The price spike only temporarily slowed reclamation projects, as soil and marine clay excavated from domestic infrastructure projects plugged the gap. However, these materials are slurry, more difficult to consolidate, unlike sand, the granular materiality of which complies wonderfully with engineering formulae, enabling those cunning transitions from liquid to solid with minimal mess or threat of subsidence. The securitization of sand in multiple stockpiles in Singapore eerily mirrors what happened in the extractive sandscapes of its origin: similarly sized dunes bloomed along the banks of mangroves in Koh Kong, Cambodia, like a dream herniating into reality, an invasive species of landscape bursting at the seam where the land met the water, still haunting riverbeds years after the dredging stopped.

Sea States and Sandscapes

In the work of Singaporean artist Charles Lim, sediment surfaces as the means through which Singapore’s sea-state, the infrastructural underside of the city-state, manipulates and negates the sea. Lim’s SEA STATE project is an ongoing series that began in 2007 with the film it’s not that I forgot rather I chose not to mention. Throughout its ten iterations, the project has plumbed the depths and limits of Singapore’s territory through works that span photography, installation, cartography, sculpture, and film. SEA STATE has been exhibited widely within Singapore as well as internationally, with multiple works forming the first Singapore Pavilion at the Venice Biennale in 2015. SEA STATE’s preoccupation with the manipulation of territory assumes multiple forms, from longform interviews with mariners and bureaucrats, to the production of maps and scale models, as well as numerous atmospheric and oneiric films of storm drains, reclamations, and caverns. Lim’s work is notable in terms of the access he has been granted to the key projects and sites of Singapore’s expansion, from the excavations of the Jurong Rock Caverns, to the military training base of Pulau Tekong, to the Tuas Megaport reclamation. The name of the project itself evokes the oceanographic description of the surface condition of a body of water, where sea state 0 is “calm (glassy)” and sea state 9 is “phenomenal.”

Charles Lim, SEA STATE project. Courtesy of the artist.

Lim’s background as an Olympic sailor figures heavily into SEA STATE, the project inspired by his frequent sailing collisions with clumps of reclaimed land throughout Singapore’s waters not yet marked on the map. In the video work SEA STATE 9: proclamation (2018), sand, as disguised sediment, becomes the protagonist of Lim’s project as both landscape and process, in the kitsch fantasy of reclamation itself.8 Previous works in the series have included fleeting shots of sand piled high in barges, as in SEA STATE 5: phase one. For proclamation, the profusion of sand also marks a change in tone, as the austere and occasionally claustrophobic atmosphere of previous video works is abandoned in favor of stately, cinematic poise. The nine-minute-long video is composed of scenic drone’s-eye shots of the Tuas Megaport reclamation, interspersed with the construction of a public housing project. Seams of sand stream into the sea, then the shot cuts to precarious isthmuses of grains that barely rise above the waterline that excavators are traversing, unsettling the distinction between figure and (literal) ground. Vertical shots show dredging boats and barges full of sand recently replenished from undisclosed sources, as well as jets of sand streaming onto larger reclamations, embroidering the pile with the collapsing and reforming of countless grains, setting up wider, panoramic glimpses of land surfacing from below. Grandiose ambient music sifts through the film as the panoramic expanse of the Tuas Megaport reclamation is revealed. While the imagery and soundtrack ape the cadences of the contemporary advertising sublime, Lim does this by foregrounding the most contested and opaque practice through which the city-state geophysically projects its sovereignty.

Given how the film plays like promotional material with euphoric swells of music, Lim renders farcical the fantasy of reclaimed land through dubiously sourced rudiments of city-statecraft. His work inverts the paranoid gaze of the state, which is reluctant to even admit the sight of sand streaming onto mounds consolidated and calibrated. This kind of work is normally kept out of sight behind physical partitions as well as the labyrinthine contractual involutions of procurement arrangements, until it is seamlessly assumed by the whole, consumed by land as a homogenous legal entity, simultaneously metaphor and metonymy. Land as metaphor: the lawful guarantee of its integrity, its wholeness beyond dispute; land as metonymy: this land standing in for the nation itself. The drone’s-eye view Lim deploys occasionally twitches due to the human hand correcting the flight path, the calculative unease lurking behind the unveiling of the stately grandeur of this ambiguously sourced territory. In exposing its construction, these conceits are not upended; unmasking can be massaged into the magisterial sight of the state: behind the mask, another mask. The work still abides by its limits: the furthest it can drift is where the sand barges and ships enter the maritime waters of Singapore from the legally undisclosable sources of its origin.

The eponymous proclamation in the work’s title is the legal mechanism by which a piece of reclaimed land is “proclaimed” as state land proper by the president. A reclamation can only become state land by the text of a proclamation, a eucharistic procedure which purifies the land of its ambiguous sedimentary origin. Prior to that it is foreshore or seabed, but once it has been proclaimed, “thereupon that land shall immediately vest in the State freed and discharged from all public and private rights which may have existed or been claimed over the foreshore or the sea-bed before the same were so reclaimed.”9 The overhead shots of incoming sand barges are as close as Lim’s work gets to the source of this abundance of excised sediment, the untold ton siphoned off from landscapes unnamed, legally nameless places, all dissolved in the solvent of the proclamation.

The limit to seeing like a state is that the state has a way of doing things that it can’t see, and of refusing to register that which does not meet its threshold of intelligibility. It blinds itself through the loophole, the nondisclosure agreement, the handshake and its subtle para-political fission. This is why the incorporation of footage from SEA STATE 9: proclamation into Lost World, a short film by Cambodian-American filmmaker Kalyanee Mam, forms an undercover postscript to the still-ongoing SEA STATE project.10 Mam’s previous 2013 feature-length film, A River Changes Course, traces the life of three Cambodians as they negotiate economic transformation and socio-ecological devastation. Lost World begins in a similar vein, at the scene of the crime in Koh Sralao in Koh Kong, Cambodia, a coastal province where tens of millions of tons of sand were dredged and exported to Singapore. A woman named Phalla narrates the misfortune her village suffered as sediment was extracted from beneath their feet. She journeys through the sedimentary frontier to her village, making her way through the aftermath of extraction amongst the mangroves, towards the destination of millions of tons of sediment that used to flow, deposit, erode in the rivers of Koh Kong. She appears at stockpiled dunes of construction sand at one of the aggregate terminals on the fringes of Singapore, tentatively taking a handful before letting it fall through her fingers.

Lost World, directed by Kalyanee Mam, 2018. Courtesy of the artist.

The film then abruptly cuts to an overhead shot of a sand barge unloading a small dune, the hull splitting open, water and foam leaking in as the sand itself leaves a dirty colloidal trail on the blue-green water, the first of a series of short clips from SEA STATE that pop up throughout Lost World, and specifically clips from SEA STATE 9: proclamation. Gone is the stately ambient music wafting through SEA STATE 9’s majestic scenes; instead we have Phalla’s voice narrating the scene, as if it were there all along, describing the fundamental terms of the transaction that neither she, nor anyone else in Koh Sralao, consented to. The nationalist sublime of SEA STATE 9: proclamation is retrofitted into a narrative of environmental excess and recess, by a voice that directly recriminates what is being shown on screen.

Phalla leaves her mangrove to find out why the ships are sucking sand from beneath the water, and wants to see where it went. Instead of the sea she encounters an artificial city, with its manufactured climate and prosthetic coast, boreal plants entombed in cooled conservatories that resemble generation ships of an interplanetary neoliberalism. Phalla says as much: “If this was real, imagine how beautiful it would be.” It could be that she means that “were it not for the artifice, it would be beautiful.” Or it could mean that “this is all a lie, a deception,” an elaborate concealment of purloined soil. She goes on to say: “This land is my land,” which pierces the allegorical delirium of the Gardens by the Bay, a large nature park in Singapore. Marina Bay was reclaimed in the seventies and eighties, when most of Singapore’s production of territory used its foreshore sand and hills to cut and churn into fill material. At most, there could be some undeclared Malaysian or Indonesian sand, scraped from the bottom of the Straits or nearby islands, but not a grain of Koh Kong. While none of this land, not the Gardens nor the rest of the Marina Bay, was reclaimed using Cambodian sand, the broader claim still stands: Singapore’s continued economic prosperity depends on the speculative projection of its territory through unequal economic exchange, disguising it through fabulations of sovereign ingenuity like the Gardens by the Bay. Mam’s film throws sand in the gears of the global city, marking the asymmetry between its curated artifice and the remote terraqueous landscapes this curation predates upon, unsettling the ground on which the city-state projects its most delirious fictions of sovereignty through stolen sediment.

A World Extracted

At the beginning of Lost World, and through the transplanted frames of SEA STATE, we already see where the grains of Koh Kong, piled numberless, probably went. But those very spaces of nondescript hinterland are the logistical and industrial engines which make the Gardens possible. Lost World may solely designate the environmental predations of sand dredging in Koh Kong at the behest of the city-state, but read together with and against SEA STATE, the sheer colonial and postcolonial history of geographic expansion and environmental transformation implies that there are still further worlds to extract for reproducing the global city. Urban form rewired by geo-economic fortune and political repression subversively enroll land and labor into its globe-spanning machinery: it needs to keep on expanding to stay ahead of whatever anticipated global economic movement will buoy it in the future, rooted to the spot on its journey elsewhere—because elsewhere is coming to it. The question still remains: Why get bigger? Why accumulate territory? Certainly not for the pittance of ground rent, given the investment in sediment, the sediment-as-investment, the vestment of sediment as flesh for the bone of terrain and geo-economic calculation.

The transmutation of Singapore’s development trajectory is not historical, but contemporary: Singapore is the global city as a centripetal conjugator of space-time, funneling either term through supply chains that pass through it to produce territory as a plasticity commensurate with the uncertainty of the world market. What Lost World does not mention, but which is implied in the rest of Lim’s SEA STATE, is that Singapore is its own lost world. The calamity it visited on the population of Koh Sralao was first pioneered all over Singapore and its outlying islands in the name of necessity, modernization, and the nation, displacing Orang Laut and Orang Pulau communities, who faced a choice to either abandon their maritime ways or resettle further afield in Malaysia or Indonesia.11 Many of Singapore’s southern islands were grafted together and erased by land reclamation, with Jurong Island in particular becoming an agglomeration of eighteen different islands, their Malay names now lost, sunk together into the catacombs of a dedicated petrochemical refining and storage complex. Instead of being haunted by the sediment it has reclaimed its land with, and the rhythms and ecologies this sediment subtended, the global city and its subcontracted tendrils haunt those vestiges of maritime and riverine life bound by sediment like a vengeful ghost, compelled to repeat its actions, and to forget them in the projection of another tabula rasa.

To “reclaim land” is a sly euphemism for constructing land in the sea where there was none before. The Singaporean government has plans to reclaim over 150 more kilometers by the end of the century, and is willing to spend around $1 billion a year until 2100 to mitigate sea-level rise.12 Whereas previous phases of land reclamation underwrote the city-state’s ambitions as a logistical, petrochemical, and financial node of the world market—with sea ports, air ports, business districts, and oil refineries, not to mention the sinisterly named Marina Bay Sands hotel and casino, all built on bespoke prosthetic territory risen from the sea—the next seventy-seven years of geographic growth will be built on the terrain of mortal survival, as their 2100 climate plan attests.

East Coast, Singapore, 2020. Source: Christian Chen, Unsplash.

One of the newest blank spaces on the map is the imaginatively named Long Island, which will extend along the East Coast of Singapore, where sixty years ago the first reclamation projects of the independent city-state took place, displacing kampongs and coastal communities into high-rise flats with modern amenities. Less prominently featured in the mock-ups for this project are the quantities of sediment that need to be sucked from the estuaries and rivers of Southeast Asia, leaving them turbid and ravaged. As the latest phase of territorial prosthesis, the plans for Long Island seem to have learned the discursive lessons of earlier projects: instead of a massive mound of sand dumped into the sea and consolidated into load-bearing soil, so far the Urban Redevelopment Authority, the city-state’s master-planning body, has been keen to stress the adaptive ecological potential of this barrier to sea-level rise. Scenario planning for Long Island and future reclamations is rife with nature-based solutions for rising tides, including coral reefs, mudflats, floodplains, and mangroves, creating win-win situations for sea defense biodiversity, so that citizens and permanent residents will enjoy infrastructure as a series of complex ecosystems offering the pleasures of flora and fauna in addition to geophysical security.13 But after the controversies associated with the country’s immense thirst for sand, where it will secure fill material for this key strategic project is currently unknown. While new techniques for reclamation and less sand-intensive forms of geographic expansion are being developed, all of these make still massive quantities of sand even more important to secure, as sand becomes the geophysical margin of minimum territorial integrity that will bolster other materials and modes. Excavated soil and marine clay are too slurry by themselves as reclamation infill and require layers of sand to become stable.

Singapore’s continued expansion under the auspices of climate resilience will exacerbate the unease reclamation churns up, both beyond its borders through its voracious demand for sand and border contentions with Malaysia, and within them, as sandscapes subsume coastal histories and ecologies. Lines of sand are sprayed to form the perimeter of a reclamation project, carving a demarcation into the water years if not decades before the land itself is reclaimed. Sites of reclamation may be visible, but they are never completely accessible. This is either because they are the tenderest sites of the city-state’s paranoia, off-limits, hidden behind tall fences, guarded, and surveilled, or because of a more impassable obstruction: the site of reclamation is itself not fully accessible to the individual. As the sand streaks from the spout of a dredger, it has been preceded by years if not decades of prior surveying and planning: these precisely calculated quantities of sand are the hinge that an entire architecture of integrated economic and spatial planning turns on. And years and decades later, after a project is finished, it shifts the geography of Singapore around it, as the city-state Rubik’s-cubes itself into newer and more productive arrangements, renewing its model of governance and reaffirming its tabula rasa through the endlessly pleasurable plasticity of its earth-writing.

Reckoning with the instrumentalization of sand as a resource means reckoning with how geomorphological flows collide with the speculative material practice of a global city seeking to tailor itself to the demands of the world market, carving out future niches through internal geographic expansion. A profusion of territorial prostheses will bloom over the next few decades to secure the city-state’s future amidst sea-level rise. The self-styled global city has yet more of the globe to incorporate into itself.

Vince Beiser, The World in a Grain: The Story of Sand and How It Transformed Civilization (Penguin, 2018).

Pascal Peduzzi, “Sand, Rarer Than One Thinks,” Environmental Development, no. 11 (2014).

Heinz Schandl et al., Global Material Flows and Resource Productivity: Assessment Report for the UNEP International Resource Panel (United Nations Environment Programme, 2016).

Gray Brechin, Imperial San Francisco: Urban Power, Earthly Ruin (University of California Press, 2006), 106.

Walter Leal Filho et al., “The Unsustainable Use of Sand: Reporting on a Global Problem,” Sustainability 13, no. 6 (2021); Orrin Pilkey et al., Vanishing Sands: Losing Beaches to Mining (Duke University Press, 2022).

Abdullah Abdul Kadir, “The Hikayat Abdullah,” trans. A. H. Hill, Journal of the Malayan Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society 28 no. 3 (1955).

Millica Topalovic, Constructed Land (ETH Zurich Department of Architecture and Future Cities Lab Singapore, 2014).

See →.

Foreshores Act, 1987.

Kalyanee Mam, “Lost World,” Emergence Magazine, 2018 →.

Cynthia Chou, The Orang Suku Laut of Riau, Indonesia: The Inalienable Gift of Territory (Routledge, 2009).

Hsien Loong Lee, “National Day Rally 2019,” Prime Minister’s Office, Singapore →.