I had to stop writing in order to clean my desk.

I had to stop writing to speak with the angel of dust.

The card I pulled was strength not speed.

Selenite and salt and jasper: for clarity, for transmission, for joy.

Something in the body reaches for something outside it, writing it into invisible circuitries.

I’m thinking into earthwork and mining and reframed perception. Toward the relation between mines and the invention of hell, of mines and the troubled histories of labor; the uses and properties of the human.

In the so-called western history of thought, looking for the wave that rises like a wall, a serrated line from one shore to another.

I’m listening for the bell, for the machine to stop, dishes in the kitchen, the location of someone I love, my system crashing as the sprung door bangs shut.

I’m sitting in a north so bent by its own systems that it banks its truth claims as Inevitability. The sound of a finger pointing away from what it’s done as if it could not have been otherwise, so the bodies of the future will pay off the past, buried in unsearchable code.

I am listening to Octavia Butler’s quantum thought, not science or fiction but the field that resides between thought and feeling. The capacity for thinking beyond narrative event or recorded fact.

What happens when the cards move, what risks you feel at the threshold, the animal fear that you won’t come back from wherever it’s taking you: the “it” that is thought.

…

I am thinking of the technologies of holding things together. The center of the button industry attaching itself to a river so full of mussel shells you could walk across it, where someone saw a world that could be machined and sorted by girls and women, all this happening because the woods had been clear cut and the town was out of work, and the thought was there of making something out of materials perceived to be free.

I’m caught in the undertow of its momentum, not behind me but up ahead. Something between an imaginary beginning and an unseen end.

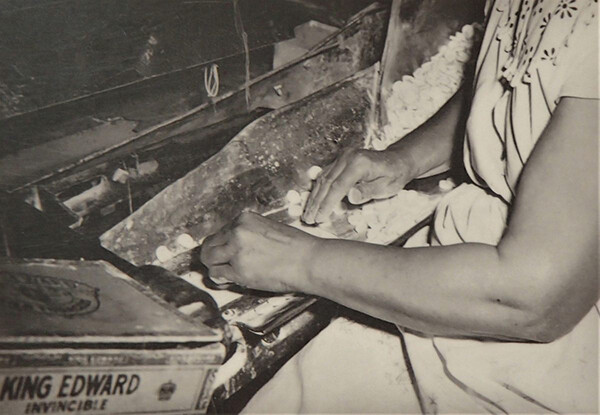

The shells would be soaked, steamed, drilled, and polished, think of the dust. KING EDWARD a few inches from her hand: the factual proximity of leisure to labor, divine right to nonunion wage work, invincibility to precarity.

A woman works at a grinding machine circa 1950.

In the dense air, buttons are sewn onto cards and everything else is thrown back into the current.

A century back, less than an hour away, I see it only with the mind of someone else’s eye.

I place the world headquarters of the pearl button industry next to Rabindranath Tagore’s Angel of Surplus, Howardena Pindell’s punched out numbers, the despair underwriting our talk of how to hold something together while so much is systematically dismantled.

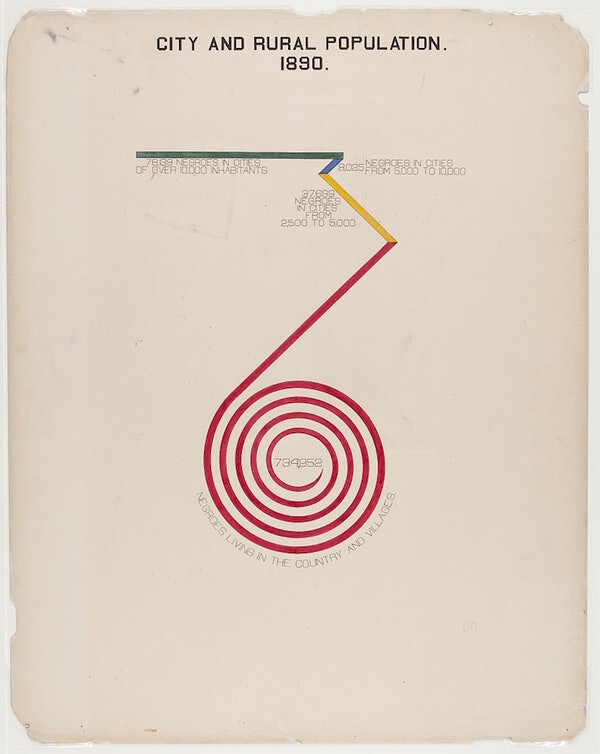

I am thinking about the spiral of W.E.B. Du Bois’s data portraits, the body as a body of facts, the touch of economics on the skin.

I’m thinking of the landscapes of extractable wealth, their labyrinths, their underworlds.

I’m thinking of Paul Robeson playing a miner onscreen, the ways he enacted or mirrored forms of burial and displacement. I’m thinking about the premiere he refused to attend.

Histories rewired, unrepaired.

…

At the turn of the twenieth century, Du Bois’s images were presented to the Paris Exhibition with his extensive research on Black life in America as living information. Rearrange the data points so someone will look long enough to take the tired facts into the cells of their interior.

Artwork by W.E.B. Du Bois. Photo: Library of Congress / Courtesy Cooper Hewitt.

In the era of psychical research and the spectrification of religious experience, the work of the data portraits is the work of perspective. Something in them exists beyond the diagrammatic, reaching into the space between portrait and landscape.

A crosscut interval, a working into art. To those who had no ears to hear, here are eyes to see. To make of what is known a revelation, a formal pressure toward the work of consciousness.

…

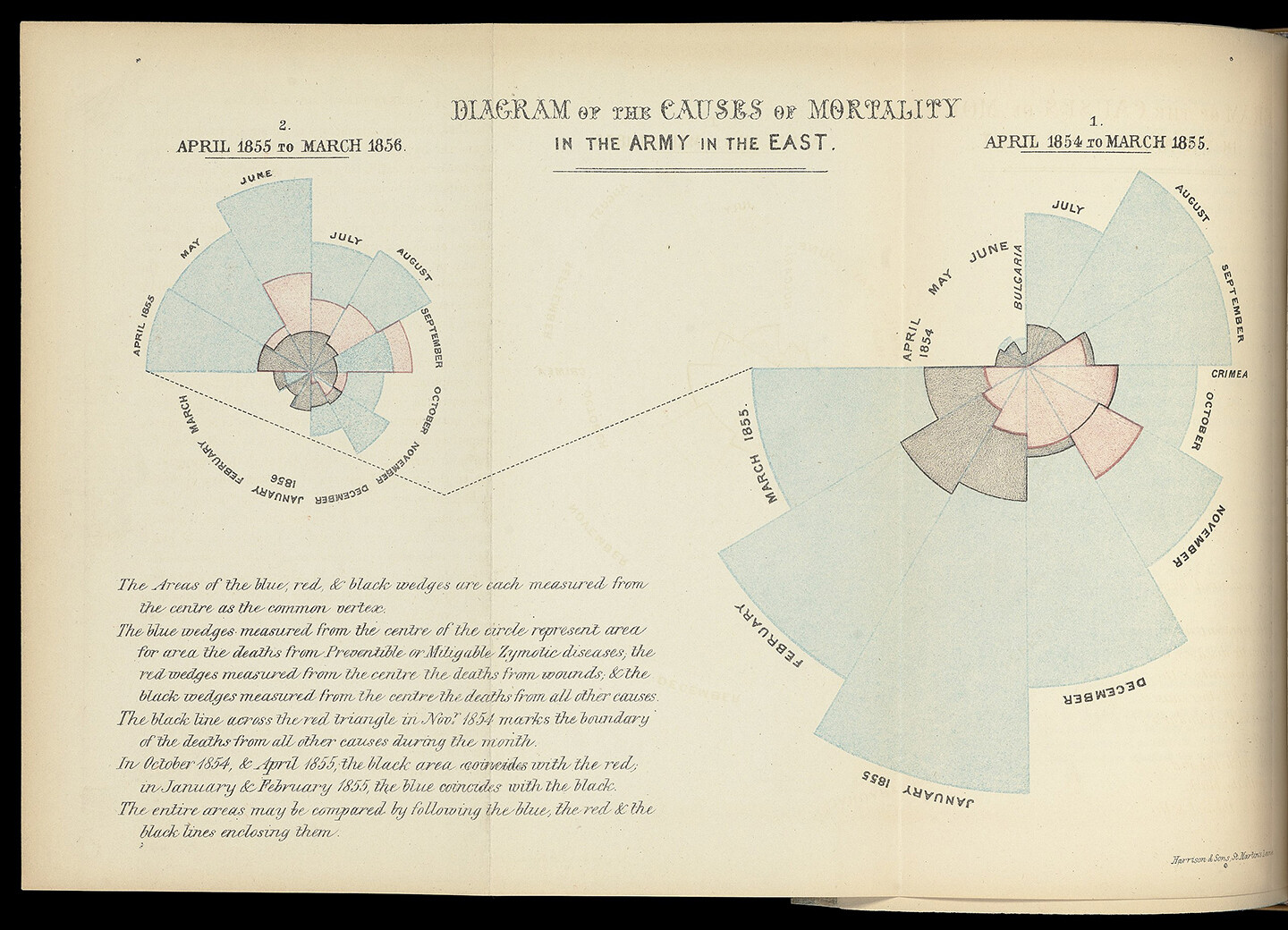

Or: a nurse in the Crimean War notices that fewer bodies survive the hospital than the fields. To make the men who overlook her work begin to see, she draws the kind of diagrammatic flower that is called a rose chart.

Some of Du Bois’s data portraits, like the nurse’s rose, suggest the curve of the modern labyrinth echoed in Robert Smithson’s spiral jetty, which in turn rhymes with the geographically adjacent Bingham mine whose downward spiral is visible from space. A wound big enough to surpass the past’s ability to correct itself.

From above, the jetty looks like a fiddlehead fern. Or a tightly wound question, on the tip of a tongue.

How does anybody sleep.

…

I’m thinking about George Oppen’s sense of the “mineral fact” and what it has to do with the orientation of a subject to its origins. He’s looking at the war by which his body is now linked with the bodies of others in a species of kinship. He’s living out a tale written by a mind obsessed by the instability of facts as if he remembered it by heart.

Do I think or feel this: it matters that the arc of Octavia Butler’s thought begins by looking back not ahead. History too is speculation. What have you done, what has been done to you. Otherwise you repeat “history in oblivion.”1

I’m thinking about Smithson’s use of mirrors in his “non-sites.” The making of spaces that reflect the viewer while throwing into shadow the factual world behind them. Wherever you look, the unflinching landscape looks back. It has all the time in the world. In this surrounding consciousness, the vast listening space you call Nothing reflects Nothing back.

I’m interested in the presumptions the work—or the artist—makes in thinking of spaces like the Bonneville salt flats as places for art, and I’m troubled by the troubled way such works participate in other forms of extraction. Their existence as gestures, as systems of pointing that cannot escape their own status as elite, saleable, beautiful things.

The obviousness of it interests me: Smithson’s earthworks—the jetty, the unfinished arc of the ramp—as inverted mines, locations of abandonment. As were his writings: A Heap of Language?

When Smithson sought the financial support of the mining companies was he imagining it as a kind of reversal or repair or was he just trying to make you pause at this flash in the desert, a moment of revelation on the Eisenhower highway to hell.

Sometimes I want, like Smithson, to simply point at something and walk away.

…

Of mineral facts I know little, but I know that the problem of governance, like the heap of language, is a problem of both matter and spirit.

I know that the arsenic and heavy metals entering the air above Smithson’s spiral jetty are connected with the extractive processes of Kennecott Copper’s open pit mine on the other end of what has been called a Great Salt Lake.

I’m thinking about minerality as a quality and “mineral fact” as a concept, the suggestion within them of objectivity, and how subjectively different these concepts are among the poets identified with Objectivism. There was the appeal too of its historical connection with labor consciousness and social/ist - communist activism.

Where does the feeling of Oppen, the son of a diamond merchant, meet that of Lorine Niedecker, whose cabin was surrounded by mud with every spring thaw.

Niedecker contemplates the role of water in the transport of Minnesota iron and places it next to the fact—the motion—of iron in the blood: a diagram of entangled identity.

I’m thinking about the minerals required for bodily homeostasis, about magnetism and its relation to those salts, to the contact kept alive by a repeated molecular spark.

I’m thinking about the ways Octavia Butler writes through kinship and risk, recording the physical damage to Dana’s body in Kindred: not only the violence inflicted in the historical past but the damage inflicted by transit and transmission, inseparable from this accrued experience. Crashing into the residual, relived violence is the compounded violence of being permeable, of feeling even for those who perpetrate one’s harm. The exhaustion of that, what it costs, what it extracts.

…

In the imperfect wobble of the glass that separates my desk from the world outside, a woman stops on the sidewalk across the street. She wears two large backpacks, one facing forward the other back, and carries a large shopping bag in each hand. When she pauses, she sets down the two bags in her hands but leaves her packs on.

I’m thinking of how often I’ve been that person having a private moment in public space, aware of how easily I could wander off the map and wondering who had seen it.

What is the pull of the mineral fact of such a thought.

It was Linnaeus who broke the world into three varieties he called kingdoms, but he owed most of it to Aristotle. Who is the king of the kingdom, who says what distinguishes the crow from the Japanese maple or the petrochemical waste in which my food is wrapped.

It occurs to me that procedurally there are many things I can no longer do, that one path or another has blown up before or behind my view of the road. This too a mineral fact: any situation may demand the reinvention of both self and relation, what it means and what it costs to hold something together.

The condition of empathy in Butler’s speculation is a disability in the world at large and a superpower for the writer as long as she can survive the beatings of the onslaught that surrounds her.

It is clear in the parables that it is Butler not her protagonist who is writing scripture; or rather, one writer exists within another. Here is a path, here is where I fell, don’t let feeling throw you off your game. Yes, it is too much. Turn the page over. Write it down.

Theresa Cha