Liam Gillick’s intervention in the permanent collection of Berlin’s Museum of the Ancient Near East, titled Filtered Time, opened to the public in April 2023. Using light, color, shape, projection, sound, and almost no text, his intervention comes at a time when the Pergamon Museum, in which this collection is housed, is projected to close at the end of 2023. In March it was announced that the entire building would not only have to close for four years to await the delayed reopening of the classical winig, but that the completion of the overall renovation wouldn’t be finished until 2037, at a cost that might run up to €1.2 billion.

The Pergamon is a neoclassical building that first opened in 1930. It houses the so-called Collection of Classical Antiquities, including the monumental Pergamon Altar, as well as the Museum for Islamic Art and the Museum of the Ancient Near East. The latter includes the Babylonian Ishtar Gate, another monumental reconstruction based on excavations made by German archeologists in the period of the German Reich’s alliance with the Ottoman Empire from the 1880s to World War I.

Gillick agreed to realize his project amidst difficult debates about how to deal with these buildings and the fraught colonial histories they house. The conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

—Jörg Heiser

***

Jörg Heiser: Can you talk about the invitation you received to intervene in the permanent collection of the Museum of the Ancient Near East?

Liam Gillick: The invitation included secret information that the building would close after the project, at the end of 2023. But then I was told that it might stay open after all. So it wasn’t clear. The invitation also related to a lot of new research on the original coloring of the artifacts, and that they were looking for someone who could think about color. The archeologist Shiyanthi Thavapalan has written a number of papers that question dominant ideas about language and color in Mesopotamia, and I had already read these because of my involvement in the 2022 show “Color Is Program” at the Bundeskunsthalle in Bonn, which was also another example of trying to work with people within an institution.

JH: And a German institution, at that.

LG: I think the invitation came because it was already evident that I’m capable of surviving one or two years’ work with a German institution and their strange rules, self-imposed restrictions, and cultural obligations. None of that really bothers me, but I said almost immediately, I can’t do this if it will be focused on the artifacts, but I can do it if we’re thinking a lot more about the place. That said, I immediately got hold of the plans from when the Pergamon Museum was first conceived, in 1910, and made a model. Only the plans turned out to be wrong, because so many details changed when the building was rebuilt after World War II. And if good drawings were made of the repairs then I don’t know where they are and I had no access to information about the wiring of the building or the internal structure of the walls. The invitation came from the director of the Vorderasiatisches Museum, Dr. Barbara Helwing. It was decided early on that we might need the support of a contemporary art institution, so Sam Bardaouil and Till Fellrath from the Hamburger Bahnhof, National Gallery for Contemporary Art became the collaborative institutional partners.

JH: There’s a big controversy in Germany now about the renovation and expansion of the building, according to plans made by architect Oswald Mathias Ungers before his death in 2007. The museum is scheduled to close to the public for at least three-and-a-half years, and the entire building won’t be finished until 2037, at the earliest.

LG: I’m sure if Ungers was still alive, he would have changed the plans, which involve complicated reconstructions to allow for a “quick tour”…

JH: … right, based on 1970s ideas initially projected for quick tours for tourists of the Vatican and the Louvre, which were later abandoned. In any case, it seems a colossal and costly mess.

LG: There were at least four architects engaged with the Vorderasiatisches Museum throughout history: there were the first plans by Alfred Messel, finished by Ludwig Hoffmann after Messel’s death in 1909; then there was Ungers, whose plans are now continued by others; and the first director of the Pergamon Museum’s Vorderasiatisches section when it opened in 1930, Walter Andrae, was also an architect. He followed the model of German contextual archeology, which is to mark out the urban plan of Babylon and then collect fragments of that. They have more bricks in their collection, I think, than anyone else, which is really perverse and wonderful. So you go to the storage, and there’s just thousands of bricks.

JH: But then again, isn’t it weird that, as far as I know, no less than 80 percent of the glazed bricks on display were made in the Berlin region?

LG: Yes, and what I find interesting—as someone who grew up in a barely understood postmodern sweep, which was very exciting to me, and still affects me—is the fact that you’re already looking at a confection. And it continues to this day: they’re still perfecting how to create the appearance of something. This surrounds some fragments.

JH: As you mentioned, most of the German archaeologists involved in the excavations of 1904 to 1914 at the Babylon site, what is today Hillah in Iraq, were architects.

Excavations of the Babylon site resumed after the end of World War I.

LG: They called themselves Ausgräber or “excavators.” And Andrae’s 1961 autobiography was called Memoirs of an Excavator. It is a rather more direct and straightforward word than “archaeologist.”

JH: This also points to the fact that you were aware that you were getting yourself into a thicket of fraught history: of colonial extraction, of neocolonial wars. In 2003, in the wake of the US invasion, the Baghdad Museum was looted, and then in 2015, ISIS destroyed numerous sites, including the Mosul Nimrod site.

LG: They engaged in a consistent program of destroying idols, as we did in Europe and elsewhere during the Reformation, especially in England. It marks my upbringing, the lack of images. But one of the most destructive acts was the Americans building a helicopter base on top of the Hanging Gardens of Babylon, which is an extraordinary act of cultural vandalism and indifference.

JH: Clearly you’ve done a lot of research, but interestingly, there’s very little text in your intervention. Can you talk about this choice?

LG: I thought about using a lot of didactic stuff, and then I felt distinctly that it’s not my moment to speak. I can point and allude to things, highlight things, maybe confuse the tour of the building a little bit by slowing people down, making things look better or worse in the light.

JH: The initial deals regarding the Pergamon Altar and the Ishtar Gate were struck in the context of an alliance between the German emperor and the Ottoman sultan in the 1880s and the early twentieth century respectively. In regard to the Pergamon, the agreement was that one third of the findings would remain with the owner of the land, one third would remain with the Germans, and one third would remain with the sultan—and then the Germans managed to secure the land and to negotiate a swap with the sultan. As for the Ishtar Gate, a first substantial part was brought to Berlin after negotiations with the Ottoman antiquity authorities in Constantinople in 1904 and a second part in 1926, after a similar negotiation with the Bagdad Museum. So in the end, they got more or less everything.

LG: A couple of people at the museum said to me, well there are contracts. I couldn’t tell whether they meant it seriously or ironically … but the thing that you hear the most in relation to the history and scientific judgment is, quite correctly, “We don’t really know.”

I believe that the question of restitution is both more simple and more complicated than it appears to be. Some things in Western museums are not what they seem to be: the Ishtar Gate, for example. And other things are clearly what they seem to be: they’re from somewhere else. The German model for these institutions is much more like a university than the museums we are used to dealing with as contemporary artists. There is a scientific, not indifferent, feeling that, well, this is history. And the people working here have more in common with the archaeologists and researchers in Turkey, Iraq, or Syria than they do with me.

Having said that, the Pergamon is a place that has been adjusted and fixed up every now and then in order to endure, and it has symbolic power that’s used politically. And the Ungers reconstruction would be the final erasure of all that complex layering, at least aesthetically.

JH: In the museum you also encounter a history of opaqueness, obscurity, and didacticism. So you have new wall panels that are in German, English, Turkish, and Arabic, providing information about how some of these artifacts got to be there. And then you have other wall panels, which are only in German and English, which briefly describe what you see in aesthetic terms. And then there are other artifacts that don’t have any description at all. And you’re left to your own devices, which are, for a layman like myself, rather scattered or fractured.

LG: I had written short, unauthored texts about every room for the book accompanying the intervention. And it was only the day before the opening that they suddenly thought about putting those texts on the wall. But they don’t have a system for this; it’s not consistent: the information is not in Kurdish or any of the other languages spoken in the region. I find that to be significant coming from our position, where we’ve spent the last twenty years thinking about art as research; art as the exhibition as a form; the question of didactics; the documentary turn. But I thought, I’m just going to let go of the question of texts initially because it suits my interests, rather than trying to tell everyone what’s going on.

JH: At the German Pavilion in 2009 you took the leaflet for the visitors, the didactic element so to speak, and stuffed it in the mouth of the animatronic cat that was part of your installation. Which is a gesture about this question of didactics, and what is communicated.

LG: I told the guards and the guides at the Pergamon to follow the principle of the museum, which is to be indifferent to what I’ve done, to pretend it’s not there. And they were very anxious about the reaction from the public. But I was convinced that there wouldn’t be one, because most of the visitors have never been before: they wouldn’t know what else to expect.

JH: In other words, many might take your interventions with light, color, shape, projection, sound, and almost no text as something that is simply part of the general display.

LG: In a contemporary art space, visitors are preoccupied by the question of how an object is changed by its entry into that context. Here, it’s different: you can see that people have decided they’re going to educate themselves. This means there are profound differences in the way people behave in this building compared to the way they would behave in a contemporary art space. I was very aware of this. That’s why the exhibition map that I put up is the wrong way round. It’s from an early exhibition tour plan that I found in storage, a recommended route, which is completely bonkers and involves a lot of doubling back through spaces. So I just made it more useless.

JH: The first of your interventions that the visitor encounters is an eighth-century-BCE statue of Hadad, the Mesopotamian weather god, which is a huge outdoor stone sculpture. You decided to do something that immediately made me think of films, or more precisely horror films. You have projected blue eyes onto the sculpture. Apparently, there were originally objects there, perhaps jewels. And there are ominous sounds, of shipyards or industrial spaces. And the processional street that starts there, leading to the Ishtar Gate, has a very filmic quality.

LG: There’s a room (Room 12) where I project the original ink and watercolor sketches that were done under the instruction of Walter Andrae. They look like film or theater storyboards, to test out various constellations for the rooms and the organizational principles. And these are from the 1920s and early 1930s, when Siegfried Kracauer was writing about film and Gabriella Tergit was writing about Berlin. All of that was part of the same continuum of a kind of business of serious-minded entertainment. They bought lots of stuff for the Pergamon from the Crystal Palace in London when it went bankrupt in 1911, because they had already built an Assyrian palace there. And everyone would have been aware that they were making an experience, that it was staged.

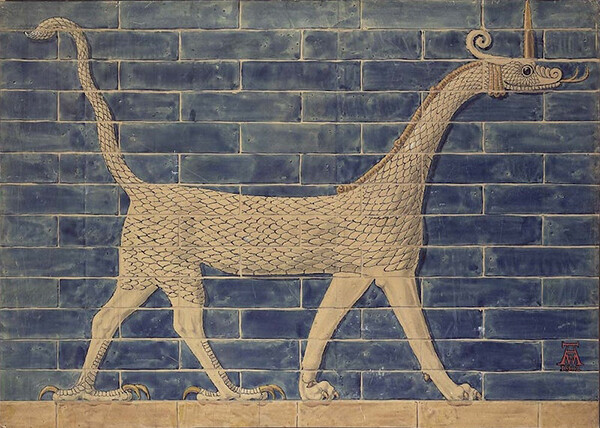

Walter Andrae, reconstruction of bricks with a mushussu (dragon) from the Ishtar Gate, 1902. Watercolor and graphite on board. © Staatliche Museen zu Berlin – Vorderasiatisches Museum. Photo: Olaf M. Teßmer.

JH: They wanted the impression of an entire architectural setting rather than of an assembly of singular objects.

LG: I’m convinced that Walter Andrae—as an anthroposophist, an adherent and follower of Rudolf Steiner—was also hoping to reach this kind of astral plane where you could see all the future and all the past. He was envisioning the Ishtar Gate as a means to spiritually prepare the young. The original drawings reveal that it would have felt much more modern in the 1920s than it does today.

JH: And also even more cinematic? It was the great era of the German movie industry, from Robert Wiene’s The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920) to Fritz Lang’s The Testament of Dr. Mabuse (1933). But the Hadad sculpture with the glowing eyes also made me think of The Exorcist (1973), which has this bizarre opening scene set at an excavation site in Hatra, Iraq. There is a life-size sculpture of the Mesopotamian demon Pazuzu. It’s a premonition of the demon taking hold of the girl Regan. It’s like an explicit version of the central trope of othering, characteristic of the entire horror movie genre—the idea of the demonic evil as the outside other that invades you, a kind of projection or reversal externalizing the colonial guilt. Was this cinematic aspect on your mind?

Still from The Exorcist showing Father Merrin and the Pazuzu statue, 1973.

LG: As soon as I abandoned the idea of using text, I had to think, what have I got? I found out early on that one of the people on the technical team, Tomas Thomas, had worked on a number of German films and television series as a lighting assistant. And Hadad was the very first thing we did. I wanted it to have eyes, and I wanted it to constantly be in motion. We did it quickly and roughly. It felt very much like cinema. And that’s the approach I used after that, because I realized that it works.

The cinematic aspect also comes to the fore in the monumental early 1930s paintings above the exhibits. These paintings—which are not recreations of what it would have looked like in Babylon, but of the archaeological sites at the time—depicted as extraordinarily desolate spaces, empty of people. And these paintings are combined with dramatic stagings reconstructed out of fragments. All of that served to spiritually prepare visitors to encounter the Ishtar Gate—visitors who might have just been at the shopping arcades in nearby Friedrichstrasse.

JH: The central path through the museum leading to the Ishtar Gate consists of a base of glazed bricks with motifs of lions and flowers in mostly blue, orange, and turquoise. Then there is a kind of beige abstraction of a higher wall and then the castellated top, again with the richly colored ceramics. Going across the abstracted part is a searchlight, which recalls a prison or flak searchlight, something menacing in any case. And it immediately draws the eye. At the Ishtar Gate itself you installed a continuous hammering sound, as if somebody was still working away up on top of it. All of that brings home the idea that this place was cinematic from the very beginning.

LG: I agree. The searchlight leads the viewer’s eye towards something that is a stylized, imaginary thing, and yet that is not entirely made up. For Andrae, this movement is what it’s all about: at the beginning, you see the stone lions of Sam’al set into the edges of the wall, followed by the processional street, and then the Ishtar Gate. Well, none of this makes sense. It’s something between cinema, theater, architecture, and the symbolic potential of the artifacts. And the Pergamon is still talked about as having symbolic power, which is why the current situation is so confusing, because the original promise was that it would never close. But it will close.

JH: The opening scene of Peter Weiss’s monumental novel The Aesthetics of Resistance (1975–81) is set in 1937. Three young guys go into the Pergamon to see the altar—which you currently can’t see because of the ongoing renovation—and he describes how the three, who turn out to be members of the Rote Kapelle anti-Nazi resistance, see the slave work that went into making it. And at the same time, you hear that people like Albert Speer took inspiration from the altar for the Zeppelin Tribune at the Party Rally Grounds in Nuremberg. So, you have the overdetermination of these pieces throughout the twentieth century.

LG: Already in the nineteenth century, there were big battles about Mesopotamian and Babylonian findings, as to whether or not they’re any good in comparison to Hellenistic art and architecture. The British—certainly the director of the British Museum—did not think they were any good.

JH: Because it had color.

LG: It had color. We know that when the Assyrian panels were painted, the skin tone was relatively dark. You can see traces of it. In 1937, the then-director of the British Museum, John Forsdyke, ordered the cleaning of the Elgin Marbles––they were washed forty times in bleach to make them white. So you can see this desire to cleanse as part of an idealization of form that was in tension with the gypsum or limestone panels from Assyria.

JH: You could say the Pergamon Museum settled into an easy opposition: here we have the clean white Hellenistic heritage, and there we have the Oriental colorful heritage, and we put them side by side for you. The historic irony being that the opposition is completely bogus. Hellenistic sculptures were polychromatic. Knowledge of this was suppressed and only resurfaced in the last few decades.

LG: The Mesopotamian findings were a popular sensation when they were first displayed in Europe in the nineteenth century, even though the academics thought they were second rate. But they found a way to use them as a subset of the German and British construction of identity and ethnicity. According to this historical continuum, Assyrian art operates in relation to Greece and Rome as proto-Germanic culture is to its fully realized expression. And that was an argument for elevating Mesopotamian artifacts somewhat in the same way that Britain did with Scotland, and its myth of clan tartans, largely invented in the nineteenth century.

JH: The side rooms to the left and right of the processional street contain more traditional vitrine displays. There is, for example, a copy of the Uruq vase from 3200 BCE which depicts a hierarchic cosmology: nature at the bottom (fauna and flora), and then you have slaves working away bringing that stuff up to the priestesses and priests. When we walked through the exhibition, you said, that’s like Brexit England today. Nevertheless, that’s a piece you didn’t work with. How did you decide what you would work with or respond to?

LG: I approached the whole thing in accordance with one of the enduringly interesting things about making art, which is to be annoying and unhelpful, even indifferent or destructive. Saying that, of course I talked a lot to the director of the Vorderasiatisches Museum, Barbara Helwing. And she did point things out to me. And I pointed things out to her. In some cases, it had to do with moments of intensity, and moments of speed and slowing down, and moments of wondering. What am I supposed to be looking at? Or what’s supposed to be happening here, when there’s nothing really happening? This is also what cinema can be: the feeling that I’m not sure what’s happening at this moment, but that it will become evident later on. The drive from the researchers and the director was very much towards education. Whereas I’m more interested in power, institutions, and affect.

JH: In the space which also holds the copy of the Uruq vase, you introduce the sound of someone walking—a kind of stern headmaster walk.

LG: Which is actually an archive recording of someone walking through a museum.

JH: I find it striking that you decided to have singular, identifiable sounds, not soundscapes. Very simple—say, something that sounds like someone banging on a pot.

LG: I did bang on a pot. As in Venice, I’m trying to find a space in between things. And one way to do that is to use sonic effects that are weak. It’s hard to make a weak gesture in a place that is so powerful. It’s so overwhelming that it needs a kind of pathos in the approach, in order to also indicate doubt, on a concrete level. I realized that what I’ve got to do in each instance is to have a cycle that appears and fades or appears, that is never stable.

Attempts to highlight the use of color in other museums always involve either a stable version of something that’s been painted, or they gradually fill in color to a point where you can see it completely. What I do is a bit like that, but slightly different, because the thing that interests me is ambiguity. The whole exhibition is an exhibition of curtains, light, and ambiguity and shift. And that’s what artists can do. That’s what I think about a lot, and have always done.

JH: There’s only one point where you use an historic photograph, which you project onto the floor. And it’s undulating, as if coming in and out of focus. Which made me think of discussions that are pertinent to memory studies, to the whole question of commemoration: Can you depict atrocities, including the cultural atrocity of colonial excavations? If so, how do you depict them? And how do you represent them?

LG: It’s a fairly weakly articulated but quite precisely political element. It’s hard to find photographs of the excavations. There are some, but not many. Mainly they are photographs of a European man in a suit and hat with the local workers digging in the background. And this is still how it operates today somewhat. I needed to represent this somehow. And I wanted to do it quite brutally. So you have a choice: Do you walk on these people, again, or do you step around them? It’s a symbolic gesture.

My approach to the show was affected by having spent so much time in Bonn for the Bundeskunsthalle exhibition. I went to the Haus der Geschichte museum about ten times. When they depict something difficult to deal with, like colonialism, or aspects of the guest-worker program, they do it earnestly, carefully, with dignity, and so on. You’re supposed to be cautious before you go into the room about the Red Army Faction, and you’ve got to be dignified and solemn when you look at pictures of the Turkish guest workers in the 1970s, and you’ve got to be celebratory about the opening of the Kaufhof department store or the economic miracle of the 1950s. Everything is as it should be—and yet it also feels like they have everything completely the wrong way around.

That gesture with the photograph is connected to the question: How are you going to behave? That was the subtitle of my German pavilion: “How Are You Going to Behave? A Kitchen Cat Speaks.” How are you going to behave here? It’s what ties my work historically to the tradition of, I’d almost say, satire. There are elements like the Hadad sculpture, for example, which is rendered as relatively friendly. They call him the “menacing sculpture of Hadad” but if you bathe him in orange light and give him shiny blue eyes, his mouth doesn’t look so scary. Maybe he wasn’t scary.

Similarly, I wanted to show the documentation of the people working on the original excavations as being in a state of flux, because that is the condition of our understanding of this exchange of labor. I’m more interested in production than consumption, so I want to know how this place is produced—not how we consume it. That is what the whole show circles around: that’s why the searchlight points onto the Weimar-period walls, that’s why the projection is undulating, etc. It’s not so different from how I worked in the early 1990s when I had limited resources and I might do a show with some sawdust on the floor and some blue gel lights. At one point I was just going to overwhelm the whole museum with the victory of contemporary art—but I didn’t, in the end.

JH: There’s the life-sized ninth-century BCE relief of figures from the Nimrod Northwest palace, the original of which is in the British Museum. Your intervention there could easily be mistaken for a more typical kind of museum didactics, because you have projected onto the figures the colors that at least approximate those that they were originally painted in. But then you told me that you actually used RAL colors, a German standard dating back to the 1920s.

LG: Yes, it was set up in 1927 by the state, as the “Reichs-Ausschuß für Lieferbedingungen,” which produced forty standard colors. And I’ve used that standard ever since I started making objects. And, of course, these colors are used for the same reason as those on the Assyrian wall reliefs: because they are striking. Deutsche Post yellow is in there, and the regional Bahn red, and the gray of the boxes by the side of the Deutsche Bahn railroad, and so on.

This is the kind of thing people might not see, but they might feel it a little bit. Do they need to be told this via a wall panel? I’ve got to make decisions. This is all I can do. I could simply reflect the current thinking in archaeology. But I need to introduce another side which is associative, a sort of parallel thinking. And the parallel thinking is that at the time, in the 1920s, they were looking at these things and were wondering what color they were, at a time when Germany was shifting, or certain authorities were shifting—also because of technology—away from esoteric thinking about color and work towards regulating and making uniform.

JH: The projection starts with a kind of anthroposophist spectral coloring that then resolves into the outlining of the figures.

LG: Yes, the idea that these objects were always in the same condition is impossible. They were painted, not glazed. Paint comes off. And they were clearly designed to be seen from a distance. We know that the feathers of the genies, these spiritual beings that fertilize and bring messages from the gods, were painted alternately red and blue. So, from a distance, they would look magenta.

As I mentioned, Andrae was a follower of anthroposophy. For him, the color on these things did emerge from this peculiar Steineresque idea of meditation, modesty, deep thought, openness to the power of feelings and affects. I reject the romantic as an ideal, but I’m fascinated by the moment of decision before you pick the word to write down or the color in which to paint something. And I’m not sure that decision always comes from clarity.

For example, it is generally presumed that jewelry on these figures was painted red, in reference to the rarity of red gold, and so on. But I’m not sure that’s correct: the color may have been lighter, the chemical of another color might have degraded. My point is that the underlying scientific presumption is that there is a system of signification to be repeated. But what if it’s not quite as rational as this? By this I’m not exoticizing the Assyrian artists; I’m exoticizing the thinking of a 1920s museum director. That is something I do often in my work: try to shift the order of representation.

The followers of anthroposophy had clearly articulated anti-Semitic views of various types, albeit veiled. Steiner believed you could still get in touch with these ancient civilizations that the Jews had somehow confused and complicated, because, of course, we know that Assyria and Mesopotamia existed because they’re in the Bible. And when in fact the archeological traces were found, people like Walter Andrae wanted to find a spiritual, symbolic reason for it. I wanted to just represent that a little bit.

JH: Your work always follows a methodology, although it takes various forms. If you describe a spectrum with Michael Asher and the idea of negation and subtraction in response to the institution at one end, and at the other end, Hans Haacke and Renée Green, something more accumulative, more openly putting the research on display, would you locate yourself in between those two poles?

LG: Yes, because I think that the peculiar endurance of contemporary art as a space of potential or an imaginary zone is that it can accommodate a lot of things done by people who are looking for a different form of exchange and production. Forensic Architecture, for example, are sociologists, or writers, or researchers. And I think my role is to work alongside all of that in order to maintain a kind of semi-autonomous artistic abstraction. I used to liken it to keeping a big concrete block afloat in a swimming pool. You have to try, even though you know it’s impossible.

I’m fascinated by the evasive potential of contemporary art, as this arena which absorbs everything in opposition to it. In that sense contemporary art, in its developed sense, really is an offshoot of Western Marxism and Freudianism. That is a vulnerable and difficult situation, but I believe in it, whereas I’m concerned about the experience economy that has emerged around museology. Certain kinds of visitor experiences and audiovisual presences are hollowing out the idea of the display and the system of information. This is creating parallel worlds of companies and organizations that take over all the art budgets to produce these experiences. The difficulty that contemporary art caused in that world is being gradually erased. You go to the Humboldt Forum and it’s the corporate sphere versus the cultural sphere. And the corporate sphere has won completely, it’s not even close.

JH: The Humboldt Forum being the recreation of a Baroque castle which was, you might say, literally built on slavery and colonialism. Now it houses the ethnological collection in a setting that has the feeling of a shopping mall.

LG: It’s perverse. I’m not sure I could do anything in there. I think, to a certain extent, that what I’ve done at the Pergamon is appropriate, because as a contemporary artist of my age, that preoccupation with historical layering is also true of the Pergamon in its current state, with the 1950s GDR linoleum that’s visible alongside the badly done 1980s fixtures.

JH: And then there’s David Chipperfield’s newly built James Simon Gallery as the entrance building.

LG: That layering is a condition of contemporary art … and this layering will go when it gets redone. In the end, I felt much more aligned with the place than I could have imagined because it has all the components of advanced contemporary art: something to do with the cinematic, something to do with affect, something to do with traces of the past that are still just hanging around, like ideological traces that still serve as a justification for something, mixed with a quality of contingency and also pragmatism.

JH: Maybe this is another ideological background in that consumerism is very much about immersion, and a lot of avant-garde art is about the negation or disruption of immersion. But at the Pergamon any idea of immersion also clashes with the heritage of the GDR.

LG: It’s one of the last grand buildings in Berlin where you can clearly see the patchwork restoration that happened in the 1950s. And Walter Andrae was part of that process of bringing work back from Moscow before he died in 1956. But I don’t want to be an Ostalgie asshole. And I’m not, because what you’re seeing is not some time capsule of grand East Germany, it’s much more complicated than that.

What can an artist do with all this? Well, I think you could give the project to someone who has a very clear political and research-based practice. And I think that should happen, and should probably happen much more. The Haus der Geschichte in Bonn needs to be taken over immediately, because what it is doing aesthetically, institutionally, in terms of narrative, is wrong. I felt like I should try and start a campaign to shut it down. Because of the way it tells its story. You would never know the Germany that I grew up with, which was difficult, complicated, punk, refusing, artistic, it was solemn, it was drunk. It was all these different elements.

JH: That would be the West Germany of the seventies and eighties.

LG: You wouldn’t know it from that building. You’d know there was pop music but not how annoying or how difficult it could be. And there’s nothing about fucking and drinking in Leipzig, which people did all the time, because they couldn’t ban that, right? So all these things are not there. So being the artist coming in who is inappropriate and undidactic can help to break something.