Alice Wang: Do you recall your first encounter with Russian cosmism? I read that in the mid-1970s, you participated in apartment seminars on underground art in Leningrad and published articles in samizdat journals. Were you exposed to the work of the cosmists during this time in the former Soviet Union? What was it that attracted you to their philosophical ideas?

Boris Groys: In fact, during my Soviet time I was more interested in the West. I more or less knew Russian history—especially intellectual history—but I didn’t work with this knowledge. After emigrating I became more interested in Russian cultural traditions. So my imagination went in the opposite direction of my emigration. Russian cosmism at the end of the nineteenth and beginning of the twentieth centuries interested me as an attempt to, let’s say, secularize Christianity.

The basic Christian idea is that history is not accidental, not spontaneous, but teleological. Marxism’s belief in technological progress is also teleological. Cosmism combines Christian faith in immortality and salvation with Marxist faith in technology. The latter faith holds that technology can be controlled and harnessed to a certain goal. The teleological, even eschatological understanding of history built a common ground for different Russian ways of thinking at that time.

AW: What are the contexts and conditions in which the cosmists were working during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries? What was the political and intellectual climate of the time? What platforms did they have to distribute their ideas?

BG: At that time, Nietzsche’s influence was very strong in Russia. And, as you remember, Nietzsche said that Man—a human being—should be superseded by the Übermensch. According to this logic, humankind is only one stage in the development of vital cosmic energies, and humanism should be overcome by something even more vital and more radical. Heidegger also said that humanism should be overcome. And then there’s the phenomenon of technology … you can find interest in technology in Marx, in Nietzsche and Heidegger, in Ernst Jünger. In their work and others’, we see something of a utopian/anti-utopian fascination with technology as an extension of the vital forces.

Many Russian authors around the turn of the twentieth century also thought that one should transcend humanity, transcend human history, and so on. At that point they began to criticize classical Marxism’s insistence that the end of history will bring about the satisfaction of “normal” human needs and desires. Indeed, people do not only desire food and sex. They desire immortality, for example. And they desire immortality because they are not like other animals. Other animals do not ruminate on the fact that they will die. But people do—and they also remain unhappy living under a form of communism that does not promise them immortality.

AW: Before returning to the idea of immortality, I wanted to talk a little about putting it into practice. In the American science-fiction community, the writer, editor, and publisher Donald A. Wollheim used the term “cosmotropism” to describe human beings’ “outward urge” for space exploration. In 1971, he wrote this in The Universe Makers: Science Fiction Today: “I think that space flight is not a whim that happened to arise in the minds of dreamers … [but] a condition of Nature that comes into effect when an intelligent species reaches the saturation point of its planetary habitat combined with a certain level of technological ability.”1

It sounds so much like cosmism, but it was written much later. Wollheim connected our “compulsion to go out” to “a conscious drive for immortality—if not of the individual, certainly of the nations and species … For it will be our ticket to immortality. It will be the birth of cosmic humanity, of that Galactic Empire which seems to be surely part of the future once we become truly the masters of space flight.”2 For me, cosmotropism is quite real, especially now. It is no longer if but when we will migrate to outer space. No matter how much one critiques the aerospace industry, and the advancement of technology, it’s just going in that direction.

When I grew up, in the 1980s and ’90s, NASA’s Space Shuttle programs were broadcast on television. Just a few decades later, corporations like SpaceX urge developments in the privatization of space travel and exploration. Looking back from here, the ideas the cosmists proposed are remarkably prescient. Issues around interplanetary governance, human occupation or colonization of space, and other ethical questions will need to be negotiated before our departure. With climate change, overpopulation, and the depletion of natural resources here on earth, who will get to leave? These are important matters for public discourse.

Although cosmism is a philosophical framework, its thinking guides our actions. When translated into practice, its ideals are manifested in policymaking. We can’t just depend on the private sector to hold these conversations and determine our actions in space. To my mind, the radicality in cosmism is found in its no-one-left-behind attitude. You have said elsewhere that after the Bolshevik Revolution, the political party known as the Immortal Biocosmists—when elected into parliaments in Petrograd and Moscow—proposed to amend the Soviet constitution by introducing three rights on the issue of immortality.3 What was this biocosmist political party, and what were some of their proposed social policies?

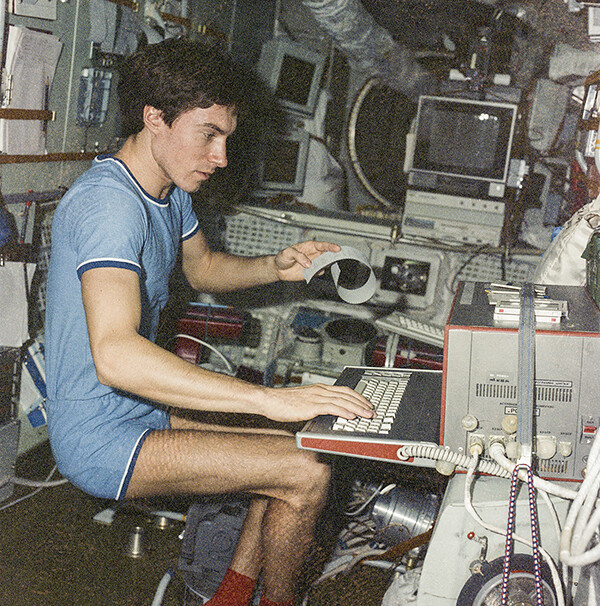

Soviet cosmonaut Sergei Krikalev stuck in space during the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. License: Public Domain.

BG: When we speak about cosmic flights and the exploration of space today, we have in mind a dynamic model of technological progress. This dynamic model of progress implies that what we’re doing now in cosmic space will be continued and further improved by the next generation, and so on. The cosmists did not believe in this model. Their questions were along these lines: Why should we be interested in progress if we don’t stand to gain anything from it? If my generation contributes something to cosmic space, how can I benefit from it? I remain mortal, and I remain eternally indentured to progress. I live now—and not in the future. If progress is defined by a dynamic directed towards the future, everyone is yoked to progress, and every generation fast becomes psychologically and physically obsolete. Already now, people ask in earnest: Should we be interested in the generation before the internet, before the iPhone, before this and that? So, we are toiling away our lives for progress, but progress denies us any sovereignty and any dignity. We are permanently discarded, so we all turn into human waste. It is not quite clear when this movement will stop. The question the cosmists thus ask is: Why should the individual be interested in progress?

It is no accident that the cosmists were politically connected to anarchism. The anarchist movements and parties in Russia were very strong during the nineteenth century. The traditional anarchist question is: How can I harmonize my individual desires with social processes? The cosmists said: I can make them harmonize if this progress promises me resurrection and immortality. Christianity made such a promise, but secular concepts of progress did not. Cosmists wanted secular technological progress to give this promise too, and in so doing reconnect every individual with world history.

When the cosmists spoke of immortality, they meant it corporeally—a concept analogous to the immortality of the artwork. Art had a central place for the cosmists. Art contains a promise that each artwork will live for a long time—maybe forever. Art is kept—in collections, museums, and so on. But to keep art means to control its surroundings and conditions. If you have a museum, you have to control humidity and temperature. If you want to keep something, if you want to prolong its life expectancy, then you must begin to control the context of its existence. The context of human existence is the cosmos. If you want to control a human life in such a way that you can prolong it as you would the life of an artwork in a museum, then you have to turn cosmic space into a kind of museum—a comfortable and sustainable environment for human beings. That is what the cosmists actually wanted.

AW: We now live in a time where many are skeptical of the utopian promises made by scientific and technological advancements, and the desire to maintain youth and vitality, as manifested in rejuvenation, anti-aging, and biohacking technologies. These technologies continue to fuel the neoliberal capitalist system in its endless cycle of consumption and production. Perhaps death—as part of the natural order of things—is the ultimate liberation from and dissent against the status quo? In his short story “Immortality Day,” Alexander Bogdanov questioned the ability of the human psyche to deal with eternal life.4 It seems that perhaps even the cosmists themselves were ambivalent about the notion of immortality. Also, what do we do with ourselves if we can live forever and go anywhere we want? Will all of this longevity be supported by the state?

BG: The question of immortality is also difficult because there is a very intimate relationship between intelligence and the fear of death. Why are humans considered intelligent in ways that other animals are not? Because animals don’t think about death, they have no fear of death. Why are thinking machines and artificial intelligence all stupid? They demonstrate artificial stupidity, not artificial intelligence—because they don’t think about death. They don’t think about the possibility of being switched off and destroyed. This is something Kubrick saw very clearly in 2001—that artificial intelligence begins to be really intelligent when it understands the concept of death. However, the moment it understands the concept of death, it begins to kill people.

Nature does not prevent the death of individual humans—it does not care about them. That is why the cosmists began to dream about a totally artificial, man-made world that could secure human existence in perpetuity. In The Human Condition, Hannah Arendt writes:

The most radical change in the human condition we can imagine would be an emigration of men from the earth to some other planet. Such an event, no longer totally impossible, would imply that man would have to live under man-made conditions, radically different from those the earth offers him. Neither labor nor work nor action nor, indeed, thought as we know it would then make sense any longer. Yet even these hypothetical wanderers from the earth would still be human; but the only statement we could make regarding their “nature” is that they still are conditioned beings, even though their condition is now self-made to a considerable extent.5

To this self-made condition belong the laws of a technological progress that is directed towards the future and permanently destroys its own past. Intellectuals and artists are often plagued by a feeling: I make effort after effort, and nothing stable comes out of it, because the next generation uses different technologies, different fashions, and they don’t respect what I have done. In our culture, based as it is on the idea of progress, the feeling of precariousness is universal. That is why the Russian cosmists spoke about immortality and resurrection: they wanted to—at least partially—redirect progress from the future towards the past. And they took the museum as a model.

AW: I can see how thinking about these bigger questions is important, especially at a time when we are all sort of scrambling.

BG: They are simple questions, but everyone feels their relevance. You know, in many of his texts Andy Warhol says that he is interested in keeping leftovers.

AW: He had this thing where he boxed everything.

BG: And he was a commercial artist. At the same time, he had a desire to keep things from being discarded, from becoming garbage. This was a reaction against our culture, which destroys everything—either through consumption or through rejection.

AW: Well, I have another question for you then regarding your own subjectivity in this climate. In your essay “Genealogy of Humanity,” you wrote:

The truly emancipated individual experiences oneself, rather, as an artwork that should be protected from decay and annihilation. Accordingly, true technology is the technology of sustainability. Thus, museum technology cares for individual things, makes them last, makes them immortal. The Christian immortality of the soul is replaced by the immortality of things or bodies in the museum.6

You were speaking about the cosmists’ desire to return the human body from being an object to a subject. This continued objectification of the body—I’m not sure if this is something I am interpreting correctly—is already happening. At NASA, for example, as part of the Human Research Program, there was a “twin study” for which astronaut Scott Kelly spent a year on the International Space Station (from March 2015 to 2016) while his genetic copy, or twin brother, astronaut Mark Kelly was on earth. According to the official report published in the journal Science three years after Scott Kelly’s return to earth, “Long-duration missions that will take humans to Mars and beyond are planned by public and private entities for the 2020s and 2030s; therefore, comprehensive studies are now needed to assess the impact of long-duration spaceflight on the human body, brain, and overall physiology.”7

The language of science always underscores the objectification of the body. I think about how language works in this subject-object divide. But perhaps the astronauts regard this case as a modern-day sacrifice. Astronauts risk death to explore the outer reaches of what is humanly possible, not unlike the ancient Mesoamerican warriors who traveled to an alternate dimension through self-sacrifice by climbing to the top of pyramids and plunging to their deaths. Maybe this image is too dramatic, but the point is that in addition to a philosophical schema, cosmism seems to also be a spiritual framework for considering our collective relationship to the cosmos.

Maybe it’s not the subject-object divide but rather the decentering of the subject. The subject is dissolved, similar to the dissolution of the ego in the Buddhist tradition—so there is no subject and object. Do you think there’s any relationship between cosmism and Buddhism?

BG: I think the problem is not so much the sacrifice itself, but whether we get compensated for it. In the Christian tradition this compensation is divine grace. In our times it is the collective memory of people sacrificing themselves for the common good. It was very characteristic of the Christian church to create an archive for sacrifice, for martyrdom.

Sacrifice is always connected to the process of archiving. Capitalism tends to negate archives; today physical archives are financially in a very bad position. This economic dissolution of archives creates a feeling that whatever we do, it all disappears—it is all for nothing. If people don’t have the feeling that their sacrifice is valued, then they just enjoy life. They think the only thing they have is life here and now, so they want their life to be a life of pleasure.

Donald A. Wollheim, The Universe Makers: Science Fiction Today (Harper and Row, 1971), 116.

Wollheim, The Universe Makers, 116.

In a 2015 conversation with Anton Vidokle at a screening of his film This is Cosmos (2014), Artists Space, New York.

Alexander Bogdanov, “Immortality Day,” trans. Anastasiya Osipova, is featured in an anthology of original writings by cosmists, most of which were translated into English for the first time. See Russian Cosmism, ed. Boris Groys (e-flux and MIT Press, 2018).

Hannah Arendt, The Human Condition (1958), 2nd ed. (University of Chicago Press, 1998), 10.

Boris Groys, “Genealogy of Humanity,” e-flux journal, no. 88 (February 2018) →.

Francine E. Garrett-Bakelman et al, “The NASA Twins Study: A Multidimensional Analysis of a Year-Long Human Spaceflight,” Science, no. 364 (April 2019) →.