Continued from “We Too Were Modern, Part II: The Tropical Ghost Is a Cannibal”

4. Pale

The natives of the island of Mactan did not actually devour Magellan, despite being described by Antonio Pigafetta as theophagically heaped under his poisoned body. On the contrary, every indication suggests that the captain’s remains were in fact preserved, saved, and displayed. According to Pigafetta, the Christian king of an enemy tribe allied with the Spaniards asked to trade merchandise for the return of Magellan’s body, to which the chief Lapu Lapu replied “that they would not part with the corpse of a man like our leader for nothing and that they would keep it as a trophy of their victory over us.”1 Through this trophy, the corpse of Magellan, Lapu Lapu and his tribe survived the circulation of their world.

Circumnavigating the earth, enveloping it within European Christianity, as Magellan and the Iberian project proposed, was nothing more than materializing a Christian totality. If meaning is, for Jean-Luc Nancy, nothing more than the sharing of being, and if, moreover, “there is no other meaning than the meaning of circulation,” of sharing itself, then the project of maritime expansion has always been intertwined with the communion of a totality of being—a European Christian being.2 Magellan’s body is the negation of this being: a trophy for the totality of death that cannot be shared, that does not fit the logic of communion and salvation, that denies any mystery of incarnation. In the dead flesh of Magellan and his conversion, in its preservation and manufacture, Lapu Lapu and his tribe encounter what is called independence.

Carl Frances Morano Diaman, Magellan’s Death in the Battle of Mactan at the Hands of Lapulapu, 2008. License: CC BY-SA 3.0

It is only possible to speak of independence, beyond a political or economic gesture, when it is revealed that the only common experience is the denial of experience—the end of experience, where one can no longer navigate, where separation and mystery are retained, and a sovereignty of each self is assured even if only as an instant, a space, or a way of life. Even though the island of Mactan would surrender forty years later to Spanish rule, it remains unassimilable in the same way that the promise of communion remains lost—its body never resurrected as Magellan. It is no wonder that to this day, Filipino fishermen throw coins at a stone in the shape of a man they call Lapu Lapu, which they ask for permission to sail and fish. Permission is necessary because, though the fishermen themselves may be his descendants, descendants of his independence, there is an impenetrable abyss between Lapu Lapu and the world, and his independence. An abyss opened through the corpse of Magellan that lies dead there, in those waters, between Lapu Lapu, his tribe, and the world, while he proves in his everlasting wounds the undisputed nothing that unites them.

It is said that on September 7, 1822, on the banks of the Ipiranga River, Brazil gained its independence. The regent of the colony, son of the king of Portugal, dismounted his horse and shouted, “Independence or death.” Thus Brazil was made. Without body or flesh, without death or abyss, as divine proclamation from the mouth of the colonizer’s representative, the greatest representative of the process of sharing a way of life, an independent country of that same way of life was born. The cry of Ipiranga is a cry of the absence of the country that is being asked for, a cry whose echoes force the word to become flesh, knowing that this incarnation will always be a leap of faith, or a leap of farce. In the absence of spirits and martyrdom, the cry remains empty through the centuries in its request for a Brazil to be made without ever having the raw material to make it. Independence or death: it’s the same as saying fill me, it’s the same as declaring the wind that carries the cry as national identity and anthem. Everything will be assimilated, everything will be spent, and everything will be unraveled between independence and death, between the colonizer becoming a settler without ever really ceasing to be a colonizer, dancing permanently across this carnivalesque suspension in a vacuum where one can be anything because there was never any ground to be something.

Perhaps this explains Jair Messias Bolsonaro and his gang’s taciturn obsession with September 7, the devotion with which his troops, painted green and yellow, would march through the streets on the national holiday sharing the same obsession with carrying out what they called the “new independence of Brazil.” But they never actually did anything. They couldn’t. Despite their virulence and brutality, stupidity and trembling fear, they were still children of the same cry for independence or death, a cry that on September 7 they want to silence with their fundament of a Brazil that has never existed.

Boris Groys understands the fundamentalist as one who “seeks a fundament even though he knows for sure that there is none.”3 If modernity begins with the emergence of the now that demarcates the self and world as opposite poles, its path can be synthesized as an incessant search for a link, a lost foundation or fundament that proves the falsity of the split and reintegrates self and world, thing and subject. With the death of the chosen foundations and all the totalitarianism that safeguarded and imposed them, the promise of modernity unequivocally decants to postmodernisms that reunite self and world by making them equally contingent, equally unimportant, ultimately inseparable in their contingency. Instead of trying to heal the split through totality, postmodern irony amputates the serious tones of the subject to remove him from his island, saying that to be in the world is to be with other beings and selves that are inseparable from things that remain dead and mute. These things, in their silence, reflect the aspirations of the subject who no longer has any right to dispute the truth. As Groys summarizes:

in post-modernity, personality, individuality, and subjectivity are thought of as signs or masks that mean nothing, have no referent. So we are inwardly torn between the ability to play freely with all sorts of cultural masks, identities, and qualities, and the fact that we always wear a mask that fixes our cultural identity. And we cannot escape this external image that society makes of us and imposes on us, as was possible in modernity. We can no longer aspire to discover our true, hidden, inner, and universal identity and break the outer, false, particular identity, because as an alternative to our external identity we find only the general game of signs in which our cultural masks have a particular significance. So we cannot throw away our masks to expose our hidden true face—and we cannot reveal the other by tearing away their mask to show their true face. The mask is the face—behind it, nothing is hidden. But on the other hand, all masks can swap places and create a carnival.4

If Brazil has always lived in the carnival of settler and colonizer, then postmodernism has progressively rendered its modern illusion more unbearable. The end of anthropophagous and paternal modernisms, with their aesthetic and political repercussions throughout the twentieth century, revealed the impossibility of being Brazil. Whether devourer or devoured, hardline or moderate, suddenly the infinite contract of the potlatch looked like a Faustian bargain. It seemed unimportant, ahistorical even. The masses broke out against their own design, choosing a mask as their true face so that it might be possible to return to the gravity of history. After all, for Groys,

this constant exchange of signs makes one uneasy. And so the desire arises to simply stop it. This desire is the desire of the fundamentalist. It is no longer about revealing oneself as proletarian or Aryan, or perhaps revealing, unmasking others as bourgeois or Jew as was the case in classical modernity. Rather, one wants to proclaim the mask to be the face—knowing it is a mask.5

Furthermore, the main effect of proclaiming the mask as the face is that “the carnival comes to a standstill and becomes a motionless scene. The world becomes a museum exhibition.”6 However, the Bolsonaro government, rather than being immobile, tried throughout its term to set off on new crusades and decree more enemies, even if they were former allies, even if it threatened Bolsonaro’s power. Each time, the line between Bolsonaro and his enemies grew broader and more irascible until it became Bolsonaro against the world—the world he himself invented from behind the mask. Although sinister, the farce is predictable. If fundamentalism wants immobility, to turn the world into a museum exhibition, if it wants to transform the mask into a face, fundamentalism not only needs to interrupt the carnival, but also to extinguish it: as long as other masks remain in play, its own fundamentalism can be deposed by a return to the game of signs. As long different masks are in play, the game will always be half farce. To preserve the fundament, it is necessary to save it from its nature, to become master of the world, the last world: a single and solitary self. If modernism wanted to share the self’s world, to establish it as truth, the fundamentalist understands that this sharing is impossible. In its absence, what remains is the dream of total independence from the museum exhibition that the fundamentalist themself curated. A last animal in their own zoo.

Bolsonaro with Russian President Vladimir Putin in November 2019. License: CC BY 2.O.

O Dono do Mundo (Owner of the world) is the name of the last book published by Plínio Salgado, Brazil’s pioneering fascist and founder of the paramilitary Integralista Party. In the unfinished book, an engineer named Adamus discovers himself as the last living human being. He wanders—unfathomably lonely, speculating innocuously about all that has been lost—from Brazil to Istanbul, passing through Lisbon, Paris, and several other cities that have become giant museums in which time has stopped. The secret to true immobility is explicit in Salgado’s last book: the desire and fear of becoming the last man. In the collapse of any hope of superimposing himself on this world, of building a social bond from his self, the world that rejected his foundation and fundament becomes a playground for his final considerations. Though frightening, it is also a prophecy of the final clash between self and world with all the chips on the table, in the construction of a true and total independence under the ashes of everything and everyone, demarcating their difference in similarity. In the emancipation of the ashes, of a holocaust without return, the long now of a self’s last and futile thought can traverse a vast environmental reserve spanning the entire earth.

It is curious that in Salgado’s novel, the extinction of humanity is linked to a machine that speaks to the engineer Adamus, the owner of the world. Among so many who credit the rise of current fundamentalism to its skill in communicating with machines and algorithms, it is impossible not to resort to Heidegger and the technological Gestell that absorbs the world, freezes it, and transforms it into the farce of an infinite reserve, a resource always ready at hand insofar as it alienates being from its temporality and transforms being itself into a resource. In a frozen time, the fundamentalist built his frozen self in the collage of what was and what will never come to be.

Marx opens his famous Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte by stating that “Hegel remarks somewhere that all great world-historic facts and personages appear, so to speak, twice. He forgot to add: the first time as tragedy, the second time as farce.”7 It is one of Marx’s most commonly quoted passages, often erroneously, but one rarely notices how Hegel’s original passage reveals a more profound consequence of the repetition of history: “By repetition that which first appeared merely in the character of luck and contingency, becomes a real and ratified existence.”8 Listening to Marx and Hegel together, it is possible to conclude that, before the reenacted tragedy makes it true, the farce makes the disaster unavoidable and existing. Perhaps it is possible to rashly say that either the farce has no end, that everything has always belonged to it, or that history is not that of the spirit of the world, that of technology or the clash of classes, but of this farce itself—silenced only with a final cry, repressed since 1822, of independence and death. Independence through death. Independence in death. It has become too dangerous to be Brazilian.

5. Intruder

Oh, big world! Who kills me is God and who eats me is the floor.

—João Guimarães Rosa, Uma Estória de Amor (A story of love)

I always stop when I remember that I am writing about Brazil. I hesitate and walk away, avoiding writing another word if I can. I never feel I have what it takes. It never seems that I have anything to say. The arsenal of so many distant unpronounceable German or French names suddenly seems wholly inadequate; it actually seems like a collection of crackling noises incapable of penetrating whatever “my” country means. My Brazil. When these two words come together, I scream with all my might that Brazil is not mine. It never was. I no longer live there. I never even chose it: Brazil was already there in the south of the planet when I found myself here.

But even if I invoke Heidegger’s Geworfenheit, being “thrown” over geographical distances of thousands of miles, the Tibetan Buddhist notion of karma, or my support for Argentina in the last three World Cup tournaments, nothing seems to dissipate the specter of “my Brazil.” The more it pulls away, the more I feel it, and the more I crave it and cling to it amidst the totalitarian, egalitarian solitude of the island of Manhattan. On the threshold of dawn, I sometimes wake up with the frightening certainty that without these two words together, I would cease to exist—I would be crushed in the irremediable compost of the world’s machine, or rather a machine already without a world, which I can envision in New York’s starless sky.

When I remember that I am writing about Brazil, I feel the need for its sky and its light as if, with them, I could finally write something. I produce countless false memories in which my grandmother, with a worn hardcover book propped up under on bed, tells me that Brazil begins and is understood only by its sky. A red songbird flutters through the blinds. A broom seller screams, announcing his brooms that nobody wants, through the filthy streets where the sound of a bucket full of water and Candomblé herbs echoes as it falls. Bucket echoing in a head that hums in a trance and in that trance asks the gods for more proximity to this sky and this light that I invent.

In the absence of Candomblé herbs, I pray for the heavens of Brazil in the New York subway. Its small and fragile lights move dizzily, indicating nameless streets announced by a demonic voice from the loudspeakers. Such an unpleasant timbre takes me back to the affectionate bossa nova that resounds in the subway stations of Rio de Janeiro, and I’m back in the embrace of what “my Brazil” calls saudade—a tacky, crude, and untranslatable melancholia attached to Brazil that still sells bad poetry and CDs of Brazilian Romanticism’s greatest hits.

I’m usually terribly moved when, from time to time, in the midst of these passing lights and their swirls of vertigo, I encounter “my Brazil”—people who speak and move in the same maternal “ãos” and “inhos,” who are in the same exile in the New York subway as my English. I want to shyly approach, simulate the affection of bossa nova on the Rio subway, share anticipation for the next World Cup, agree that the dollar conversion rate is a shame, or anything to let them know I share a bit of all their solitudes and silences. But I never say anything. I feel like I would only interrupt a world that is no longer mine. I walk away with the certainty that I never even spoke Portuguese to begin with.

The subway takes me to the Museum of Modern Art, where I visit, convinced that I’ve found an elaborate way to continue writing through an excuse to stop writing. I ask for a student ticket. I climb the stairs in a hurry as the museum is always about to close, and among so many paintings, rooms, and people, I search for the sky of Brazil. It waits for me, no matter the season’s curation, near the entrance and exit door of a more or less spacious room. The same dark blues and greens, the bright white contours, the wavy lines that transform sky and earth into a mere extension of the swing of the South Atlantic. In the center shines a shape that I sometimes call a horseshoe, a U, or even a toothless mouth, the golden and fragile moon baptizing the canvas and Brazil’s sky. Next to the yellow light it emanates, the almost-but-never-quite-human solitary figure immersed in the same tones of the painting sometimes moves away from the moon and sometimes approaches the viewer, reproducing the contortions of the passing viewer’s gaze.

Tarsila do Amaral, The Moon, 1928. © Tarsila do Amaral.

Facing Tarsila do Amaral’s Moon, I retrace the steps of Heidegger’s “Origin of the Work of Art.” I say to myself that in that painting, “the truth of beings has set itself to work.”9 That this happens because “in setting up a world, the work sets forth the earth.”10 I immediately review, as if remembering a multiplication table, the impenetrable concepts of world and earth:

The world is the self-opening openness of the broad paths of the simple and essential decisions in the destiny of a historical people. The earth is the spontaneous forthcoming of that which is continually self-secluding and to that extent sheltering and concealing. World and earth are essentially different from one another and yet are never separated. The world grounds itself on the earth, and earth juts through world. Yet the relation between world and earth does not wither away into the empty unity of opposites unconcerned with one another. The world, in resting upon the earth, strives to surmount it. As self-opening it cannot endure anything closed. The earth, however, as sheltering and concealing, tends always to draw the world into itself and keep it there.11

World and earth in strife, the essential character of Tarsila’s bluish and dark tones in their forms and subtleties. World as everything that permeates experience and whatever uniqueness our time has; earth as everything that escapes us, sustains us, and one day takes us, stripping away any possibility of any singularity of our time, of our finitude, destined to finish and renew the pile of excrement where the last men will build temples to Gaia with their bones. World and earth, the open world, instituted by everything the painting has that is unique, historical, and inimitable, for the way it reflects a time that does not repeat itself, that does not return, that cannot end because of this uniqueness.

The earth, produced by everything that is already fading in the painting, everything that disappears in its tones, on its canvas, the ephemeral temporality that it emulates and produces with its breath of death and equality. And by some miracle, in that sky that I claim to be my sky, the sky of my world and my earth in that strife, “the unity between world and earth is conquered.”12 A unity appears between being and its death, the eternal and the passenger, the clearing and the concealment, the transparent singularity in which we build ourselves and the impenetrable and amorphous clay to which we return. A unity that in its becoming and opening (which is nothing more than our own becoming and opening) is called truth: “The establishing of truth in the work is the bringing forth of a being such as never was before and will never come to be again.”13 This unique being that the work of art reveals as truth, as Aletheia, between the world that opens and the earth that closes, between the time that is given and what is taken, between everything fleeting and perpetual, is at the root of what can really be called identity. A people, a place, a light, and a night.

When I manage to feel the truth again between my fingers, I nod sadly and say goodbye to the painting, the moon, the people of a place, of a light and night. The painting, like me, is already broken, it is first and foremost a thing. Its becoming, its truth, just like me, is mute. It is Heidegger who once again details this process:

The Aegina sculptures in the Munich collection, Sophocles’ Antigone in the best critical edition, are, as the works they are, torn out of their own native sphere. Whatever height their quality and power of impression, however good their state of preservation, however certain their interpretation, placing them in a collection has withdrawn them from their world. But even when we make an effort to cancel or avoid such displacement of works—when for instance, we visit the temple in Paestum at its own site, or the Bamberg cathedral on its own square—the world of the work that stands there has perished.14

I repeat in the hope of convincing myself once and for all: “World withdraw and world decay can never be undone.”15 That painting and I, that sky and I, we no longer have a world to open or earth to produce; we are both separated from what we once meant. The painting is not my world; the painting is something that no longer produces earth, that no longer reveals, and in this transposition in which we are bought and transported and displayed like everything else, we can only whisper of damaged identities and times that no longer exist. I cannot preserve the painting. It can’t give me the sky of Brazil. Its light went out. Everything else is bullshit.

When I forget Heidegger and all his complicated words, I remember when I brought a friend—who, like me, has lived away from Brazil for some time—to see this same painting in the hope of sharing some epiphany, some feeling of belonging to dismantle German philosophy. This friend, who was pleased that the Museum of Modern Art in New York allows dogs, looked at the painting briefly and without any wonder. He didn’t know the painting, so it hadn’t existed for him until that moment. The painting, although Brazilian, was like any other that he discovered without any interest, counting the minutes until he could leave the museum. When I pressed by asking him what the painting was telling him, he immediately replied, point blank: “The painting tells me that Brazil is a space where nothing happens.”

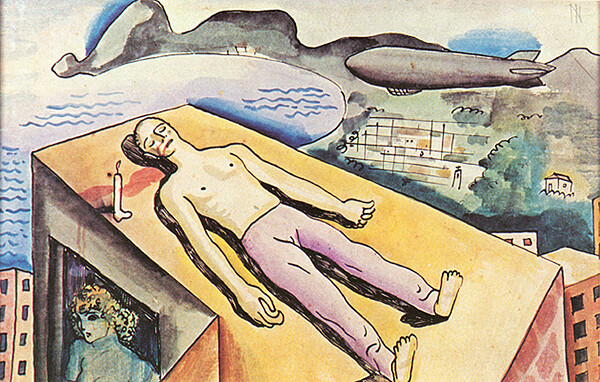

Ismael Nery, The Death of Ismael Nery, 1932. License: Public domain.

I laughed, knowing he was far more right than all my cheap sentimentality. After all, in its muteness as a thing, the picture now equated the entire reality of Brazil with its lack of becoming. Its vast and infinite space, without time. For my friend, happily adapted to an American suburb, Brazil as the picture, static and dead, had finally ceased to be a place; it had ceased to be waiting and returned to its sui generis condition of nothing happening. Open and condemned space; it wasn’t even an object anymore. It didn’t belong in his world; he had freed himself from the Southern Cross. So the light that hovers over the end of the world, only visible at the edge of the world, the light of Tarsila’s moon that always revived me and propelled me to write, didn’t astonish or curse him.

For my friend, Tarsila do Amaral’s Moon was as futile as the mirror the Portuguese contemptuously exchanged with the natives to harvest the precious pau brasil (Brazil wood). Since then, looking at that painting has felt like being no more than a shipwreck out of time, without enchantment, place, mirror, or raw material, begging the painting to reflect more than just what was irreparable in both of us, to give me crumbs of the truth I’d lost and forgotten. I wanted to beg this painting to confess to me from that moon, that light, that toothless mouth: You know, boy, we too were modern. We will not be again. We, too, were Brazilians, and we won’t be again. We will be something else, altogether different; we will discover another time, far from this absence, without settlers or colonizers, without paternal promises, without perverse mimosas. We will burn the clothes of our rapist fathers, of all the captains and their specters. Finally, in our nakedness, the blood of the world will be made into milk, the cannibals will be prophets of the sea becoming desert and the desert becoming sea. They will find the land where the dreams of the island of the self are carved, where the self finds its origin no longer in the distance, but in the intimacy of that same light that heals all history since the beginning of silence. You know, boy, it’s here, in my voice, that beginning that is always necessarily the poetry of every work of art, your sky, and all the light.

I always leave the Museum of Modern Art in New York City with no desire to write. In the rush through the serene night of the island of Manhattan and its alien lights, I am always sure that everything was written on those canvases I saw. The ugly and beautiful ones, the ones I believed in, and the ones I despised: paintings that, today and probably forever, will only speak their truth to the surrounding walls, but not to us, never again. For us, only the greatest and the most wretched hint of the worlds and earth that we have left.

Antonio Pigafetta, A primeira viagem ao redor do mundo: o diário da expedição de Fernão de Magalhães trans. Jurandir Soares Dos Santos (L & PM Historia, 1986).

Jean-Luc Nancy, Being Singular Plural, trans. Robert D. Richardson and Anne O’Byrne (Stanford University Press, 2009), 3.

Boris Groys, “Fundamentalism as a Middle Ground Between High and Mass Culture,” in Logic of the Collection (Sternberg Press, 2021), 72.

Groys, “Fundamentalism,” 74.

Groys, “Fundamentalism,” 74.

Groys, “Fundamentalism,” 75.

Karl Marx, The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte, 1852, marxists.org →.

G. W. F. Hegel, The Philosophy of History, trans. J. Sibree (New York, 1900), 312–13. Quoted in Bruce Mazlish, “The Tragic Farce of Marx, Hegel, and Engels: A Note,” History and Theory 11, no. 3 (1972): 335.

Martin Heidegger, “The Origin of the Work of Art,” in Basic Writings, ed. David Farrell Krell (Harper Collins, 1993), 162.

Heidegger, “Origin of the Work of Art,” 172.

Heidegger, “Origin of the Work of Art,” 174.

Heidegger, “Origin of the Work of Art,” 187.

Heidegger, “Origin of the Work of Art,” 187.

Heidegger, “Origin of the Work of Art,” 166.

Heidegger, “Origin of the Work of Art,” 166.

Category

Subject

Author note: This text was written throughout the now seemingly distant and blurry year of 2022. It was the year of the centenary of Brazil’s Modern Art Week and the bicentenary of the country’s independence. It was perhaps more dramatically the year of the presidential election that could have given Jair Bolsonaro a second term. Amid the confluence of these dates, and my desire to rid myself of a pressing need to address my home country in some way, I proceeded to write something that could be an autopsy of modernism as indistinguishable from a certain form of Brazilianity that has reached astronomical highs and bottomless, violent lows (like the one Bolsonaro dragged the country down into). But if my original intention was to complete this essay and then never write about my home country again, having arrived at some concluding thesis about whatever it is, was, and can be, I now see that this text is more a convulsed series of symptoms than any precise diagnosis. To the reader who has crossed this maze of untranslatability and reached here, it may point towards a further path that, like that of hopscotch, is to be crossed delicately and childishly. This path starts from all the wounds of this present, its wars and tyrants imprinted upon the farce of our identities, and unfolds within the Golgotha of history and it’s tautologies, beneath a sky whose unfathomable light we share, be it at the end of the world or its beginning.