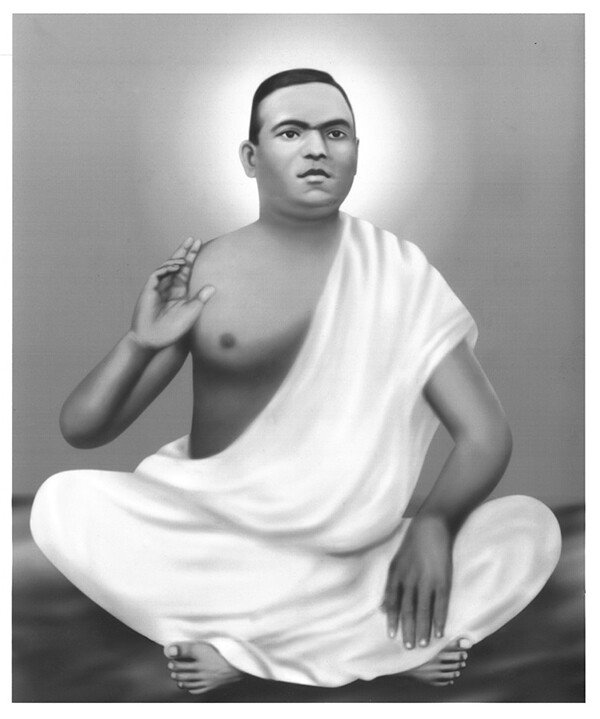

Poykayil Appachan and Social Reforms in Kerala1

I begin this oral history with Dalit social reformer Poykayil Appachan, born in 1879 in Kerala, India.2 An upper-caste family enslaved him from birth. Although this family was Syrian Christian, not Hindu (India’s castes originate in Hinduism), the fact of their religion did not shield Poykayil from the terrors of slavery. The reality of the caste system in India is one that encompasses everyone and everything. Christianity, too, has actively reproduced the mechanism of caste.3 Poykayil worked in the enslavers’ fields from a young age. While laboring there one day, he found a human skeleton. His response was to start singing. He sang with deep pain about the plight of his grandparents, who were killed in those same fields. Caste slavery used up the bodies of human beings who were compelled to plough the fields like bulls. Poykayil’s song was never written down anywhere, but has survived through oral practice. A literal translation of the song is:

No, not a single letter is seen on my race

So many histories are seen on so many races

Scrutinize each one of them

The whole histories of the world.

Not a single letter is seen

On my race.4കാണുന്നില്ലോരക്ഷരവും എന്റെ വംശത്തെപ്പറ്റി കാണുന്നുണ്ടനേക വംശത്തിൻ ചരിതങ്ങൾ

Throughout his lifetime, Poykayil sang and composed many more songs about the plight of Dalits. He sang about dignity and Dalit cosmology:

From the lands of Aryans, hail o hail!

From the lands of Aryans, hail o hail!

Brahminic Aryans, hail o hail! …

Like selling bulls, they sold our fathers

for money. We can never forget that.

And can we ever forget that?

Father sold to one place, Mother to another.

Children orphaned. Can slaves forget that?5

Poykayil’s songs show the laboring body’s connection to the surrounding ecology. Eventually, his activism turned from composing songs to advocating for social reforms through religion. To unite the Dalit community of Kerala, he created a new religion, Prathyaksha Raksha Daiva Sabha (PRDS), for caste slaves. He led many protests and built schools for the children of enslaved Dalits.

Portrait of Poykayil Appachan. License: Public domain.

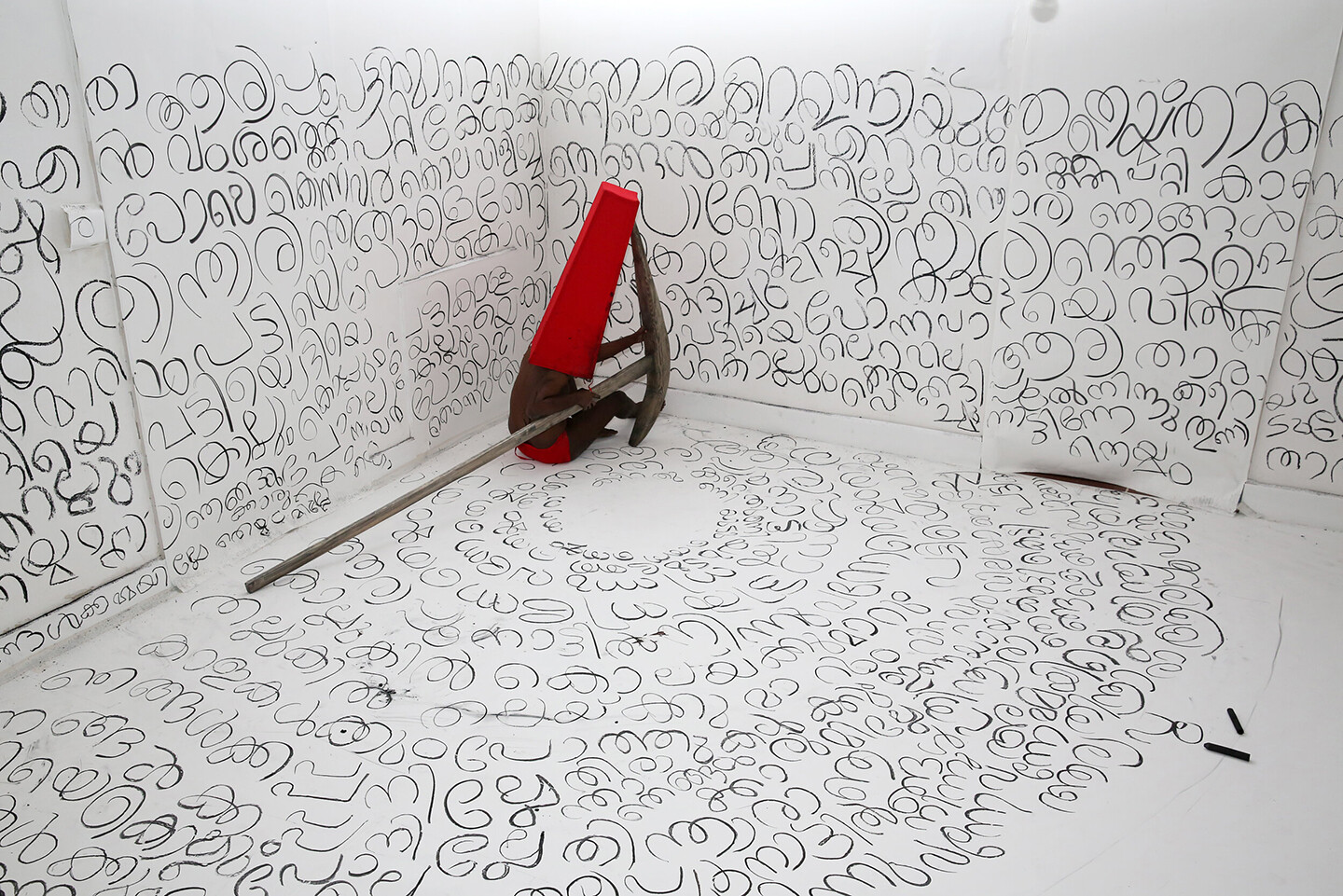

Inspired by Poykayil’s songs and his role in Kerala’s history, I coined the term “caste-pital” and created a performance and installation of the same name.6 In 2017, I performed his songs for nine and a half hours over the course of one day. In my artistic practice I write and draw—in the sense of drawing as writing, writing as drawing. When I performed Poykayil’s songs, I felt like a collective body rather than a single body. I felt communal pain, shame, fear, and power. I see my body as a meeting point for history and the present. During the performance, I carried a wooden plough that I use in many of my works. Through that plough, I tried to forge a connection with all the bodies that fell and died in the fields of Kerala.

Caste-pital was performed in the context of a public program called “Specters of Communism,” conceived by the late curator Okwui Enwezor.7 Enwezor, who often worked collaboratively, asked Raqs Media Collective to cocurate the program; Raqs in turn invited me to the Haus der Kunst in Munich. I believe this is one of the last times that Enwezor was physically present during an exhibition at that museum. I saw him there for the first and sadly last time. I have enormous respect for him and for Raqs Media Collective. One of its three members, Jeebesh Bagshi, has since been a mentor to me.

The First Elected Communist Government

“Specters of Communism” also marked the centenary of the October Revolution. In preparation for the program, I was thinking that Kerala, my place of origin, is where the world’s first democratically elected communist government came to power in 1957.8 I grew up surrounded by books that were printed in Moscow in the Malayalam language. These volumes were not only about Marxism, but also about science, among many other subjects. The Communist Party came to India nearly a hundred years ago, and maintained a strong presence in Bengal and Kerala.9 The party played a big role in social reforms in Kerala in particular. This involvement included participating in the class formation of the lower and working classes, and, most notably, actions towards an agrarian revolution. Several acts of political resistance were carried out against the bourgeoisie, against the landowners. Then, gradually, through the work of many working-class movements, a communist government was elected in 1957.10

So, the communist legacy continued, and my generation grew up in Kerala with those books from Moscow. But at the same time, the Communist Party failed in the face of the caste system. This fact must be critically addressed. For me, the performance of Caste-pital was not only about celebrating the centenary of the October Revolution, but was also a chance to reflect on Kerala’s communist government and communism’s failures with regard to caste. Nevertheless, Kerala’s sociopolitical landscape has become more egalitarian over the years because of communist movements. This is particularly evident today in the wake of ongoing right-wing Hindutva activity in the northern part of the country. I grew up seeing momuments dedicated to Communist Party workers who Hindu right-wing forces had killed. These monuments of resistance became a part of my visual memory and informed artworks like Caste-pital.

Theyyam as Resistance to Brahmanical Knowledge Production

The performance of this artwork also references a ritual dance form called theyyam.11 Theyyam carries with it a history of resistance. During the ritual, lower-caste people embody gods. Participants predominantly use colors such as red and black. Some theyyam songs, like “Pottan Theyyam,” contain explicitly anti-caste and revolutionary elements. But they also have a spiritual dimension. This brings me to frameworks discussed in historian P. Sanal Mohan’s 2015 book, Modernity of Slavery.12 The mythical stories these theyyam tell create space to think beyond dominant historiography in general, and to foreground a Dalit and Indigenous cosmology in particular. Hindu scriptures and mythology (such as the Vedas) or ancient Sanskrit texts perpetuate a discourse that insists on depicting lower-caste people as the bad ones. Caste slavery was legitimized through these myths, and “justified” through spiritual means. Over the long span of thousands of years, such myths have been compromised and appropriated through many more stories. This is what we Dalits mean when we refer to the oppressive environment long upheld through Brahmanic knowledge production. When we talk about Brahmanic knowledge production, we are talking about a hegemonic system of knowledge. Very conscious acts are needed to resist the politics of hegemonical Brahmanical spirituality. That is the responsibility of a contemporary artist living in these challenging times.

This text is an edited and revised version of an oral history interview conducted by e-flux journal contributing editor Serubiri Moses on February 3, 2023.

See a biographical note on Poyikayil Appachan by Ajay S. Sekher →.

P. Sanal Mohan, Modernity of Slavery: Struggles Against Caste Inequality in Colonial Kerala (Oxford University Press, 2015).

Unknown Subjects: Songs of Poykayil Appachan, ed. V. V. Swamy and E. V. Anil, trans. Ajay S. Sekher (Institute of PRDS Studies, 2008).

Unknown Subjects.

See →.

See →.

V. Krishna Ananth, “The Dismissal of the First Elected Communist Government in Kerala: An Abuse of Article 356 of the Constitution,” The Polis Project →.

Robin Jeffrey, “Matriliny, Marxism, and the Birth of the Communist Party in Kerala, 1930–1940,” Journal of Asian Studies 38, no. 1 (November 1978).

Ananth, “Dismissal”

“What Traditional ‘Theyyam’ Ritual Means to Dalit Community in Kerala,” The Print, January 1, 2023 →.

P. Sanal Mohan, Modernity of Slavery: Struggles Against Caste Inequality in Colonial Kerala (Oxford University Press, 2015). The book examines the relationship between spiritual practice, caste slavery, and colonial modernity. For a discussion on “Brahmanical discourse mainly rooted in the idea of divinity,” see Y. S. Alone, “Caste Life Narratives, Visual Representation, and Protected Ignorance,” Biography 40, no. 1, (Winter 2007): 140–41.