November 1985 marks a before and an after in Colombia. On the sixth day of the month, a squadron of M-19 guerrillas stormed the Palace of Justice in Bogotá. They took its staff hostage and demanded ransom from the president. A belligerent military response, carried out by the National Army of Colombia, resulted in at least one hundred deaths. Eleven federal judges died. Nine cafeteria workers were never found. For two decades, Colombia’s civil war had been raging on mountains and in jungles. Now, it had arrived in the country’s capital.1 A week later, on November 13, a sleeping giant stirred some two hundred kilometers west of Bogotá. After lying dormant for over 140 years, the Nevado del Ruiz exploded in two eruptions. From the Andean volcano’s crater surged boiling lahars, which descended the mountain at speeds of one hundred kilometers an hour. The largest of these amassed 350 million cubic meters of mud and rock slurry. This monstrous debris flow decimated almost everything in its path, engulfing the regional cotton-producing town of Armero and killing the majority of its twenty-five thousand inhabitants. Just two months earlier, Amero’s mayor Ramón Rodríguez had warned members of congress that the Ruiz volcano posed dire dangers. His pleas for evacuation went unheeded.2

Members of the M-19 wait as a tank forces its way through the entrance of the Palace of Justice in Bogotá. License: Public Domain.

In 2015, a group of journalists published The Week That Changed Colombia, an essay collection commemorating the thirtieth anniversary of these convergent crises. Each event carried with it multifarious causes and impacts.3 They transformed the relationship between state and citizenry, the latter becoming painfully aware that they were mere collateral in the game of politics. The military bombardment of the Palace of Justice, where unarmed citizens were held captive, was ordered by renegade generals who ignored instructions from the president. Officers were angered that President Belisario Betancur wanted to negotiate with the insurgents. Their attack on the palace, broadcast on national television, sent a clear message: the army was now in charge; the executive was too weak to manage such hostilities. The government’s ensuing response to the Armero disaster was characterized by inefficiency, miscommunication, and corruption.4 In the aftermath of the tragedy, monetary aid went missing. Unidentified child survivors were taken by authorities and put up for adoption. No effort was made to locate their relatives.

After November 1985, two more facts came into focus: history was indifferent to humanity, and the state posed an existential threat to Colombians. This realization implied certain understandings of the duration of the disasters besetting the nation. In his 2016 book Endangered City, anthropologist Austin Zeiderman analyzes coverage of November 1985 in the Colombian print press. He finds that reporters used the language of forewarning to denounce the government for its failure to avert the convergent crises. Several columnists played with the title of Gabriel García Márquez’s Chronicle of a Death Foretold, a pseudo-detective novel about a murder conspiracy in a tight-knit community. None of the characters in that 1983 novel prevent the assassination plot despite its details being common knowledge among all of them. One 1985 headline described the confrontation at the Palace of Justice as a “forewarned battle,” while another called the Armero landslide “a forecast apocalypse.” “We have become the land of tragedies forewarned,” so the article read, “of prophecies that come true, of prognoses that materialize.”5 Even as the siege and the eruption were treated as spontaneous catastrophes, so, too, were they framed as self-fulfilling prophecies. History was being written in the subjunctive.

Armero was located in the center of this photograph, taken in late November 1985. License: Public Domain.

As the temporal breadth of the convergent crises expanded, they acquired the characteristics of “slow-onset disasters.” Rob Nixon, among others, has written of the difficulties in visualizing catastrophes that gradually unfold, triggered sequentially by insidious forces over lengthy periods.6 These difficulties are especially acute when trying to deconstruct the phenomenon of origins and implications so vast as to be almost unimaginable. In the context of the Anthropocene, artists are increasingly tasked with what Latin American studies scholar Joanna Page describes as “taking up the challenge of representing geological and cosmic time, and of rendering visible, audible and tangible the powerful but often invisible forces that shape the planet’s systems.”7 One such artist is Santiago Reyes Villaveces, who presently lives in the shadow of the Nevado del Ruiz, and whose work uses multimedia methods to explore the volcano. His video installation Orbit, currently on view at New York’s Instituto de Visión, tells a version of the November story. The fall of 1985 is framed in an imperialist chronology, where disasters are continuities, not ruptures; this period, in turn, is embedded in the deep time of geology.

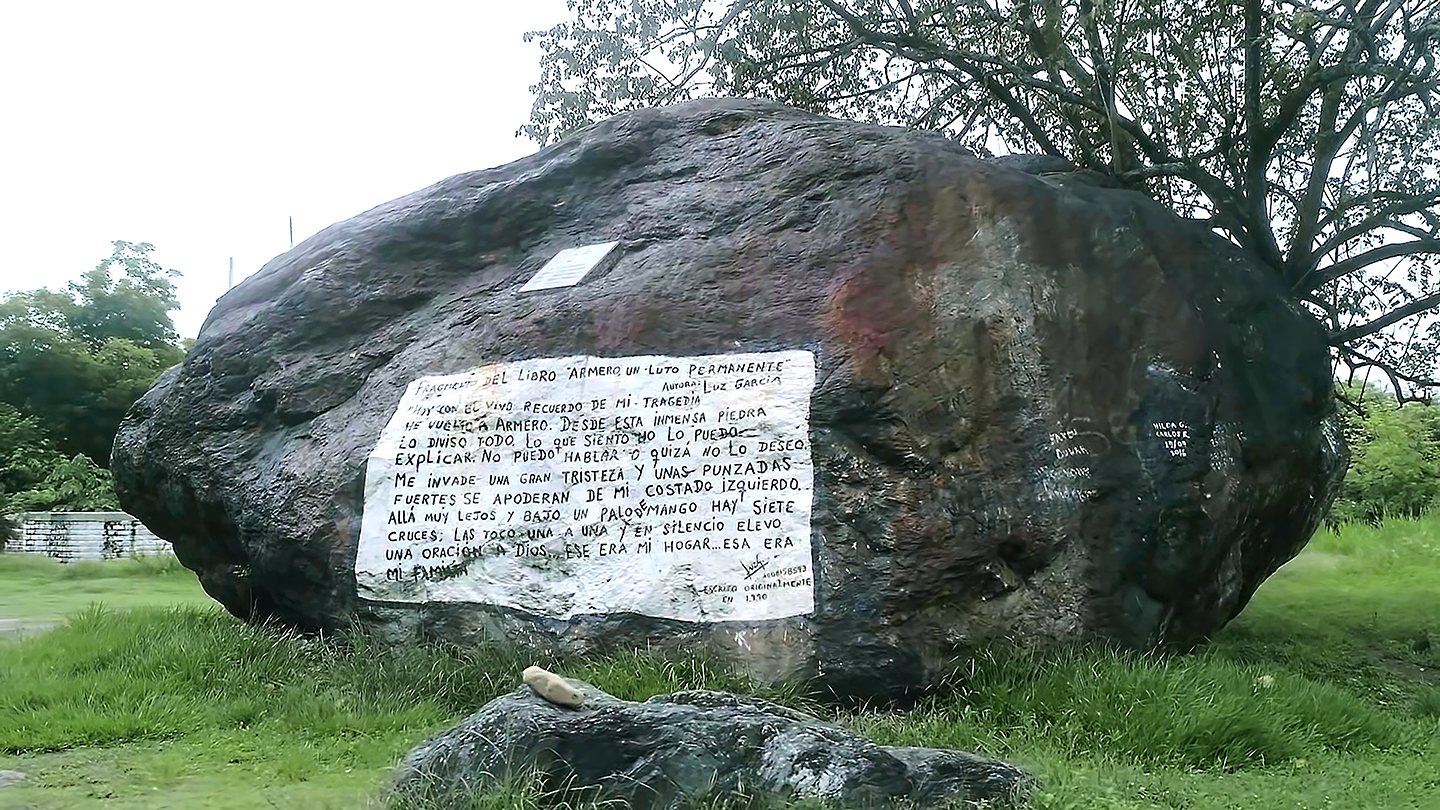

The protagonist of Orbit is a two-hundred-ton boulder that once sat at the heights of the Nevado del Ruiz. On the night of the eruption, it traveled over forty-five kilometers, and was deposited in the center of Armero shortly before midnight. Today, it is a landmark in a ghostly town that, like Herculaneum, stands in ruins. However, unlike its Italian counterpart, Amero receives no conservationist funding or legislative protection.8 In the absence of state investment, the rock has become an unofficial monument to the dead. Every year, it attracts hundreds of tourists and mourners. Played on loop, Reyes Villaveces’s video scans the surface of the rock and lingers on its graffiti. The most prominent is a mural by Luz García, who lost her family in the disaster. Her text reads:

Today I have returned to Armero with vivid memories of my tragedy. From this immense stone, I see it all. I cannot explain what I feel. I cannot speak, or perhaps I do not want to. A great sadness takes hold of me and I feel a stabbing pain in my left side. In the distance, beneath a mango tree, there are seven crosses. I touch them one by one and offer a silent prayer to God. This was my home. They were my family.9

García first painted these words on her pilgrimage to Armero in 1990, marking five years after the eruption. A picture of the rock features on the cover of García’s memoir, Armero, Everlasting Grief, published to commemorate the disaster’s thirtieth anniversary. The boulder and its inscription have since become ubiquitous in the Colombian imaginary. They symbolize the continuity of state neglect and political apathy.

García’s commemorative use of lithic matter is commonplace among the bereft. Rock, clay, calligraphy, storytelling, and tragedy have been linked since time immemorial. As Jeffrey Jerome Cohen observes, “From rock we construct graves, memorials, and dwelling places to endure long after we become earth again.”10 People sculpt stone to tell of resilience. The quest for eternity in the struggle against oblivion can be traced to literature’s beginning, itself inscribed in stone. The Gilgamesh tablet is, of course, the oldest known piece of writing. Dating from the seventh century BC, the cuneiform text chronicles a Mesopotamian flood, thought to be the same event that was later experienced by Noah in Genesis. Still, stone’s promise of eternity is largely illusory. In García’s photograph of the boulder, her words appear boldly in black. They contrast with a clean, sharp, whitewashed backdrop. In Orbit, filmed three decades later, the text is tired, worn, and faded. The bright white rectangle is streaked with red iron oxide. As it rotates, the camera shows changes in the rock’s color. Its surface is weathered and uneven. Marcia Bjornerud’s grammatical reading of stone comes to mind: “Rocks are not nouns but verbs—visible evidence of processes.”11 They are not timeless entities; they are shaped by the laws of alchemy and physics.

When speaking of Orbit, Reyes Villaveces uses the phrase “negative gravity” to illustrate the weight of history shouldered by Amero’s inhabitants and, more broadly, by all Colombian citizens. The rotation of his orbital camera reveals a ladder that leans to the rear of the boulder. In the drone’s last circuit, a man appears, as if from nowhere. His tiny frame puts the rock into perspective. This is José, a tour guide who, for a small fee, will tell his version of the Armero story. Like many others, he is a participant in the disaster economy that sustains the region. Some Armero survivors accuse José and others like him of opportunism and exploitation. By profiting from misfortune, they are likened to the valancheros, meaning mud larks or, less forgivingly, thieves and looters. Arriving in the days that followed the eruption to salvage valuables from the swampland, the valancheros formed part of the former town’s surplus workforce. Young, poor, male, brown, and unemployed, many had been displaced by the civil war that saw violent clashes between the military, the paramilitary, and guerrilla groups, including the M-19 whose members took the Palace of Justice. The valancheros’ excavations sparked confrontations between rival gangs, augmenting the eruption’s death toll. Those who uncovered buried treasure were often cursed by their discoveries. “Some spent the profits from their sales on rum and women,” notes Luz García, “and there are many who say that it only brought them ruin.”12

José, like the valancheros, interacts with the extractive capitalist regime that coalesces around the Nevado del Ruiz. The disaster industry is one branch of the export economies that dominate life in this mineral-rich region known as the macizo. Correspondingly, there looms the specter of another disaster: the European invasion of the Americas. In its inaugural exhibition, Orbit appeared in 2019 alongside seven other sculptural installations named Anus, Puddle, Navel, Brick, Fever, and Room Temperature. These works are made with gold, silver, copper, limestone, and rubber—the same raw materials that drove the expansion of the Spanish empire. Centuries later, they still fuel the competition for resources that has seen the rise of armed insurgency, leading, in turn, to the attack on the Palace of Justice. Displayed in a museum setting alongside tools of measurement and unearthing, they create an “extractive viewpoint,” a phrase from scholar Macarena Gómez-Barris. In her 2017 book on The Extractive Zone, Gómez-Barris compares this vantage to the colonial gaze. Per her definition, it “facilitates the reorganization of territories, populations, and plant and animal life into extractible data and natural resources for material and immaterial accumulation.”13 The macizo region is thus placed in a matrix of colonial relations that operates on an accumulative timescale.

Rather than regard the Conquest as a finite event, work like Reyes Villaveces’s urges us to think, instead, of a “colonial presence” that has endured throughout the postcolonial period.14 In conjuring this notion of history as perpetuity, anyone who sees such art is challenged, with Ann Laura Stoler, “to refuse the quick resort to ‘before’ and ‘after’—and even to work against the wooden, if all too common, conceptual containers of ‘past’ and ‘present.’”15 Stoler’s identification of coexistent timeframes resonates with Eduardo Viveiros de Castro and Déborah Danowski’s examination of the worlds that predate the axial revolution which some claim instigated the Anthropocene, “which, incidentally, insist on continuing to exist” despite appropriation “by the self-appointed emissaries of ánthrōpos.”16 Likewise, Reyes Villaveces approaches history as the “transformation of energy” that is contained by structures that reconfigure but never disappear.17 While exploring the combination of crude matter and abstract labor as they fuse in the creation of capital, he is drawn to the spaces that precede and exceed their entanglement in capitalist production.

Santiago Reyes Villaveces, Orbit, 2019. Two channel HD Video Color and sound, 30´14”. Courtesy of the artist and Instituto de Visión Gallery.

Orbit, Anus, Fever, and Reyes Villaveces’s other works appeared in Bogotá’s Instituto de Visión as part of an exhibition called “Lo Bravo y Lo Manso” (The Savage and the Tame), a title borrowed from ethnographer Beatriz Nates Cruz. She argues that inhabitants of the macizo reside in multiple worlds that converge around symbolic landmarks and that operate according to their own discrete laws of space-time.18 In her telling, lo bravo, “the savage,” refers to an underworld populated by the dead and the supernatural who lay claim to otherwise inhospitable sites like volcanic craters, sacred lakes, and abandoned buildings. The tame, or lo manso, meanwhile, refers to a quotidian, temperate, and teleological realm that is territorialized by agriculture, industrialization, and urban development. Tame spaces, or tamed spaces, act as thresholds between the two, setting into motion “a series of mechanisms so that a territory, a being, or an entity considered bravo or liminal can be transposed into the cultural domain with the use of symbolism or mythical discourse.”19 Taming is a cyclical, reiterative, and haunting process.

This transition between the savage and the tame is a guiding principle for Reyes Villaveces. In this moment, he says, “the savage is the state of energy in its most powerful—and sacred—material state. The tame is the manifestation of this energy when it is calm and may be harnessed.”20 Viewed from this perspective, Armero might be seen, in its post-disaster form, as a savage place. The town has been reduced to rubble. When I visited Armero, I felt the presence of unclaimed bodies and restless spirits. The lahars, which originated from the innards of the earth, brought with them malign energy from the underworld. Reyes Villaveces uses photographic technology to “domesticate” Armero, making it accessible in an urbanite, upmarket, and profitable setting. He introduces the question of scale which, as Dipesh Chakrabarty points out, is a means of extracting value.21 Notably, Reyes Villaveces is not the only artist who seeks to tame this site. So, too, does José, as he capitalizes on the pull of the eruption. In the video, José figures like Hades or St. Peter. He guards the entrance of the alternative dimension that lies beneath the boulder, reciting a cautionary tale for those who care to listen. An orator with his tablet, José serves to animate García’s epitaph. His stories of the disaster give the dead “a new verbal existence,” allowing them to walk again among the living.22

Survivors of the Armero tragedy also return to the disaster site to stand awhile next to the departed. On each anniversary, the bereaved attend commemorations among the ruins and visit the rudimentary graves of their loved ones, often marked at the approximate location of their homes or wherever they were at the time of the eruption. Local artist and activist Hernán Darío Nova evokes the catharsis that can be found in going back to the remains of Armero. In 2015, to mark thirty years since the Pope’s visit to Colombia, he made a statue of John Paul II using a stone that he found in a tributary of the Magdalena River. Erected at the foot of the crucifix blessed by the Pope, the statue is surrounded by twenty thousand pebbles representing those who died in the disaster. Using the same mineral substances that destroyed Armero to memorialize its destruction, Darío Nova aims to foster reflection, spirituality, and healing. In this, his artwork chimes with texts by authors and poets who lost friends and family in the disaster and who approximate the volcano as a means of grieving.23 More recently, he has led an initiative called Time and Memory that has seen participants use colorful string to frame features in derelict homes and place figurines on sills and mantles. These interventions make of Armero a museum curated by a grassroots collective that addresses a lack of governmental interest and that is designed to protect community heritage.

Armero, photo: Rebecca Jarman.

Armero. Photo: Rebecca Jarman.

Armero. Photo: Rebecca Jarman.

Armero, photo: Rebecca Jarman.

Confronted with this institutional indifference, we might return to the concept of negative gravity. We have seen how this phenomenon shapes a history of extraction, occupation, and conflict that propels state-making in Colombia. But it also relates to the physical matter that constitutes the Armero rock itself, measuring some seven meters to its highest point, and that of the volcano from which it originates. Indeed, the title of Reyes Villaveces’s rendition of the boulder suggests that it has sufficient gravitational pull to bring other kinds of bodies—human bodies—into its orbit. Visions of the rock, installed to create the physical sign of infinity, are accompanied by a soundtrack of live-recorded cicadas, captured in the nearby overgrowth, which the artist claims “sonically lead[s] the viewer into [the] infinity loop of the moving image.”24

On this metaphysical scale, the boulder is a remainder of the earth as a living legacy of disaster. In the early years of geology as an academic discipline, two competing geological temporalities, catastrophism and uniformitarianism, sought to account for planetary formation. The first was espoused by Georges Cuvier, who argued that the earth had been shaped by sudden, short-lived, worldwide violent events, such as Noah’s flood. The second, according to James Hutton’s claims, purports that the earth formed incrementally over the course of millennia. Read conjointly, these theories suggest that periodic crises create the conditions necessary for the evolution of life. Indeed, the rock resembles Theia, the asteroid that collided with our planet, producing an explosion of energy that created the earth’s molten core. From there traveled noble gasses through volcanic chambers, making our atmosphere, our seas, and our microbial ancestors. The existence of humanity is the outcome of an astronomical collision that was also apocalyptic. The destruction of the old engendered the new, determining the future trajectory of our planet.

One of the remarkable things about disasters—perhaps even their defining feature—is that they cause the convergence of temporalities that usually coexist, but that do not necessarily intersect, or at least not in ways that are easily discernible. The 1985 eruption of the Ruiz volcano created a collision between this dimension of geological time, which spans billions of years and the expanses of space; centuries of imperialist expansion, capitalist accumulation, and national development; and the infinitesimal scale of a single human life span. All of this took place in a matter of seconds, and just a week after the siege on the Palace of Justice—which itself was the culmination of protracted conflicts. Survivors attest that time stops as disaster strikes. As these crises climaxed, the clock stopped ticking. But these disasters also accelerated the juggernaut of history that predated that November. They spliced experiences of time into a before and an after, causing it to move in new directions. In the post-catastrophic landscape, the past transcends this rupture in time, running alongside the present and the future. Captured by its gravitational force, these temporalities revolve around the volcano on parallel trajectories, ready to collide upon its next eruption.

Ana Carrigan, The Palace of Justice: A Colombian Tragedy (Four Walls Eight Windows, 1993).

Javier Darío Restrepo, Avalancha sobre Armero: Crónicas, reportajes y documentos de una imprevisión trágica (El Áncora Editores, 1986).

Alfredo Morano Bravo et al., 1985: La semana que cambió Colombia (Semana Libros, 2015).

Barry Voight, “The 1985 Nevado del Ruiz Volcano Catastrophe: Anatomy and Retrospection,” Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research, no. 44 (1990): 374.

Cited in Austin Zeiderman, Endangered City: The Politics of Security and Risk in Bogotá (Duke University Press, 2016), 39.

Rob Nixon, Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor (Harvard University Press, 2017), 2–3. See also Timothy Clark, Ecocrticism on the Edge: The Anthropocene as a Threshold Concept (Bloomsbury, 2015) and Amitav Ghosh, The Great Derangement: Climate Change and the Unthinkable (University of Chicago Press, 2016).

Joanna Page, “Planetary Art Beyond the Human: Rethinking Agency in the Anthropocene,” The Anthropocene Review 7, no. 3 (2020): 274.

On the politics of memory in Colombia, see Cherilyn Elston, “Open Wounds: Commemorating the Colombian Conflict,” in On Commemoration: Global Reflections upon Remembering War, ed. Catherine Gilbert, Kate McLoughlin, and Niall Munro (Peter Lang, 2020).

This and subsequent translations are my own.

Jerome Jeffrey Cohen, Stone: An Ecology of the Inhuman (University of Minnesota Press, 2015), 21.

Marcia Bjornerud, Timefulness: How Thinking Like a Geologist Can Help Save the World (Princeton University Press, 2018), 8.

Luz García, Armero, un luto permanente (Apidama Ediciones, 2015), 71.

Macarena Gómez-Barris, The Extractive Zone: Social Ecologies and Decolonial Perspectives (Duke University Press, 2017), 5. See also Mariana Silva, “Mining the Deep Sea,” e-flux journal, no. 109 (May 2020) →.

Ann Laura Stoler, Duress: Imperial Durabilities in Our Times (Duke University Press, 2016), 33.

Stoler, Duress, 31.

Eduardo Viveiros de Castro and Déborah Danowski, “The Past Is Yet to Come,” e-flux journal, no. 114 (December 2020) →.

Santiago Reyes Villaveces: Lo Bravo y Lo Manso (Instituto de Visión, 2019). Exhibition catalog.

As such, they can be said to be inhabitants of the pluriverse, or the “partially connected heterogeneous socionatural worlds” that are identified by Marisol de la Cadena, among others (Marisol de la Cadena, “Indigenous Cosmopolitics in the Andes: Conceptual Reflections beyond ‘Politics,’” Cultural Anthropology 25, no. 2 (2010): 360–61). See also Arturo Escobar, Pluriversal Politics: The Real and the Possible (Duke University Press, 2020).

Beatriz Nates Cruz, De lo bravo a lo manso: Territorio y sociedad en los Andes (Macizo colombiano) (Abya-yala, 2002), 20.

Santiago Reyes Villaveces: Lo Bravo y lo Manso.

Dipesh Chakrabarty, “World-Making, ‘Mass’ Poverty, and the Problem of Scale,” e-flux journal, no. 114 (December 2020) →.

Maria Stepanova, In Memory of Memory, trans. Sasha Dugdale (Fitzcarraldo Editions, 2017), 145–46.

See Rebecca Jarman, “When Worlds Converge: Geological Ontologies and Volcanic Epistemologies in Colombian Literature after the 1985 Eruption of the Nevado del Ruiz,” Textual Practice, October 2022.

Santiago Reyes Villaveces, email to author, March 7, 2020.