At the hallway’s end, framed by the entrance to the last gallery, the monumental painting was drenched in thick, kaleidoscopic blue tones, which ensconced the all-too-familiar figural group in the center. From afar, I caught a premature glimpse of Vasily Surikov’s massive Boyaryna Morozova. On those cold nights in Lhasa, back in 1976, I had curled up in bed and stared into a slide of this painting, vividly remembering every single visage in it.

—Chen Danqing, 20111It is almost as if the thousands of Chinese who traveled to Moscow over the course of decades are considered containers for ideology first, pawns of geopolitics second, and flesh and blood individuals as an afterthought.

—Elizabeth McGuire, 20182

Prelude

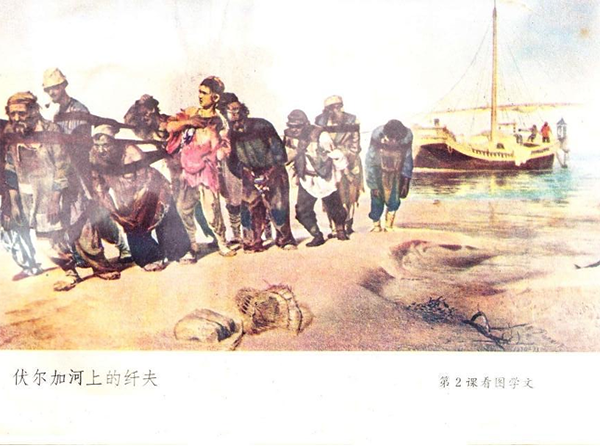

Ilya Yefimovich Repin (1844–1930), the painter whose unvarnished realism laid the foundation for socialist realism in the Soviet Union, was the preeminent villain in American critic Clement Greenberg’s conceptualization of “kitsch.”3 He also happened to be one of the best-known art-historical figures in modern China throughout the twentieth century, and arguably still is today. The artist’s seminal work Barge Haulers on the Volga (1870–73), which depicts a downtrodden group of hard-laborers trudging along a river bank, was featured as a color illustration in the ninth edition of Language and Literature (1990), a series of standardized national textbooks that have been mandatory for public education in China since 1951.4 The accompanying text, written by art historian Wu Dazhi—a specialist in French and Soviet art—provides formal analysis of the painting and a conclusive ideological message: “The working people in Russia [in the 1870s] toiled under dark Tsarist regimes and cruel capitalist exploitation. They lived in extreme pain and poverty, like the barge haulers in this painting, who had to exchange physical labor for meager returns.”5 An estimated one hundred million copies of Language and Literature were printed during the ninth edition’s run from 1990 to 2001, making Repin’s Barge Haulers a household reference and an indelible part of collective Chinese memory.6 It also indoctrinated entire generations into a certain Umwelt of aesthetics, moral persuasion, and class consciousness, “engineering” the souls of the masses.7

Ilya Repin’s Barge Haulers on the Volga (1870–73) as illustrated in the 9th edition (1990) of Language and Literature, a textbook for elementary school education in China.

At the same time, the sheer familiarity with Repin’s Barge Haulers among the present-day Chinese populace—decades after the Sino-Soviet split in 1960—illuminates a curious anachronism, both in history and historical awareness. Deeply entrenched as it is in collective cultural memory, Repin’s iconic painting has never been associated with ideological fervor nor recognized for its art-historical significance, finding appropriate analogy not in the Mona Lisa or Mao’s portraits, but in Warhol’s Campbell’s Soup Cans, which reflects a potent saturation in vernacular culture and feelings. While the Sino-Soviet split, which endured until 1989, certainly meant an “official” rupture in the historical relations between the USSR and the PRC, the actual break was far from clean given that Soviet ideology, culture, and ways of life continued to shape Chinese nation-building and everyday life in many ways, some more recognizable than others. For example, English would not replace Russian as the official foreign language taught in schools until two decades after the initial split. Furthermore, art pedagogy institutionalized by Konstantin Maksimov (1913–94), a Stalin Prize winner who introduced the drawing techniques of Pavel Chistyakov (1832–1919) as the foundation for academic training at the Central Academy of Fine Art in Beijing, continues to inform the processes through which artists are selected and trained in the academy. The list goes on: Chinese socialist monuments, urban spaces, industrial structures, and vernacular remnants remain robustly indebted to Soviet culture. The Soviet model of “systematically promoting the national consciousness” of its ethnic minorities and engaging in diplomacy in the Global South echoes widely in state-management and nation-building endeavors in post-socialist states, shaping discourses around representation and identity in the visual and performance arts.8 Even Soviet jokes have reemerged as a genre of satire and political dissent in Chinese cyberspace; the most significant example is the recent “White Paper Revolution” (which references similar actions in Russia), where the precise understanding of censure and control produces collective meaning and resistance.

Thus, the perceived split between the USSR and China created sticky historiographical conditions. Today, post-socialist/communist studies—including theory on the increasingly popular subject of nostalgia—tend to limit their scope to former Soviet states and the Eastern bloc regions. Meanwhile, research on the Sino-Soviet relationship has traditionally focused on leaders, ideology, and geopolitics, leaving mostly untouched the emotional and cultural ties developed over multiple generations. This is noted by Elizabeth McGuire in her 2018 book Red at Heart: How Chinese Communists Fell in Love with The Russian Revolution:

While the material and emotional lives of Europeans, Americans, and other foreigners inside the Soviet Union have been examined, few works have looked at the Chinese—even though some ended up as leaders of the only other great power communist country in the world. More strikingly, numerous books describe Chinese experiences in Europe, Japan, and the United States—though none of these countries was as central as Soviet Russia in shaping China’s twentieth century transformation. It is almost as if the thousands of Chinese who traveled to Moscow over the course of decades are considered containers for ideology first, pawns of geopolitics second, and flesh and blood individuals as an afterthought.9

Historian Deborah A. Kaple has also challenged the perceived separation of Maoism from Stalinism, arguing that the former is a “primeval offshoot” of the latter in her analysis of the Chinese Communist Party’s idealization of the Soviet model and its integration of high Stalinism into its own version of communism.10

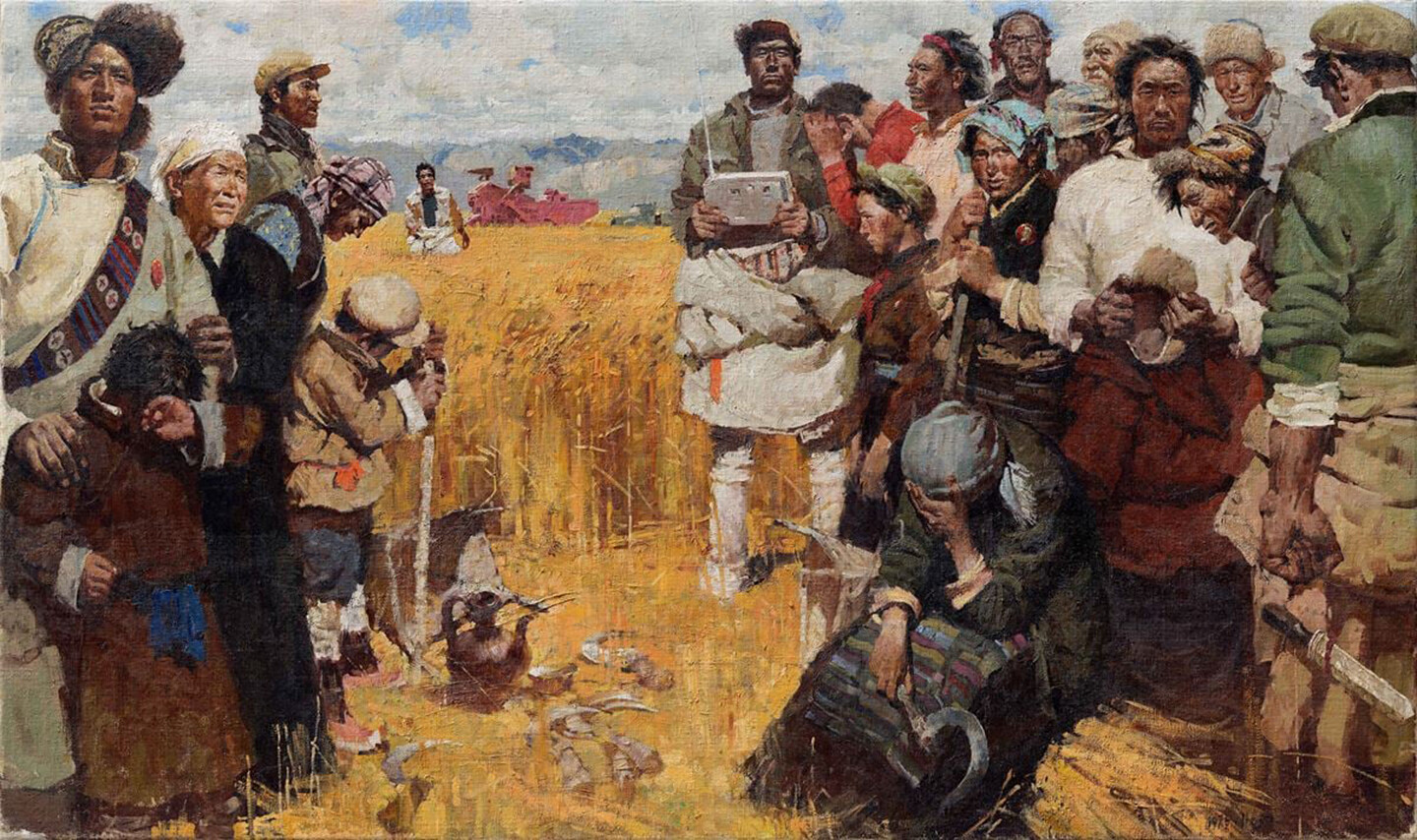

These historiographical issues have lasting implications for the practices of art history, art theory, curation, and museum collection. Within the Sino-Soviet dynamic, which has always been an asymmetrical affair, the former Soviet and Eastern bloc nations are mostly unaware of China in terms of a shared socialist lineage. Nor do they realize the extent to which that lineage continues to operate. Soviet art history—in stark contrast to the art pedagogy of socialist realism—is barely taught in Chinese art academies and is considered somewhat obscure and problematic. Most art-historical accounts of contemporary Chinese art treat the Soviet heritage (if at all) as an unexamined monolith, presumed dead and irrelevant to the agenda, aspirations, and forms of the Chinese avant-garde. It is perhaps not surprising, then, that in the entirety (some five hundred pages) of the Museum of Modern Art’s Contemporary Chinese Art: Primary Documents (2010)—part of a publication series intended to contextualize global contemporary art—a search for “Soviet” yields a single result in a footnote. “Socialist realism” is mentioned sparsely and always evoked as a simplified antithesis to what’s presumably “contemporary.” The volume, however, includes an important account by artist Chen Danqing of his nationally renowned portraits of ethnic minority groups, painted while he lived in Tibet in the late 1970s. It would seem nearly impossible to contextualize this work without considering Soviet art history, socialist-realist pedagogy, and the unique Communist Party representational policy on ethnic minorities. In a 2011 memoir, the artist recalled the intense emotions he felt upon viewing in person Vasily Ivanovich Surikov’s (1848–1916) history painting The Boyarynya Morozova (1887). This experience resonated with my own first encounter with Repin’s Barge Haulers in 2019: the painting struck me not only as an intensely familiar image, but also as the physical embodiment, and origin, of a cultural memory that is ontologically significant.

Art historian Boris Groys writes that the central fallacy in recent diversity and inclusivity initiatives in museum collection and research lies in the underlying assumption that alternative trajectories of modernism—such as socialist realism—were merely varieties of kitsch. This approach fails to escape the established aesthetic hierarchy shaped by Cold War power struggles.11 While mounting evidence suggests a global post-Soviet framework that can meaningfully account for fruitful and revolutionary conversations among generations of artists from the Soviet Union, Eastern Europe, Asia, Latin America, and Africa throughout the twentieth century, museums have continued to separate, for instance, the Soviet avant-garde, Latin American art, and Chinese contemporary art into their respective silos. The addition or expansion of these silos not only fails to enact any meaningful revision of Euro-American art history; it also reinforces this history by refusing the possibility of alternative global contexts. Art historian David Joselit laments precisely this lack of “comparative global frameworks” in his book Heritage and Debt, advocating for a “re-temporalization” of “heritage,” which encompasses “different and often contradictory world epistemologies, histories, and ontologies.”12

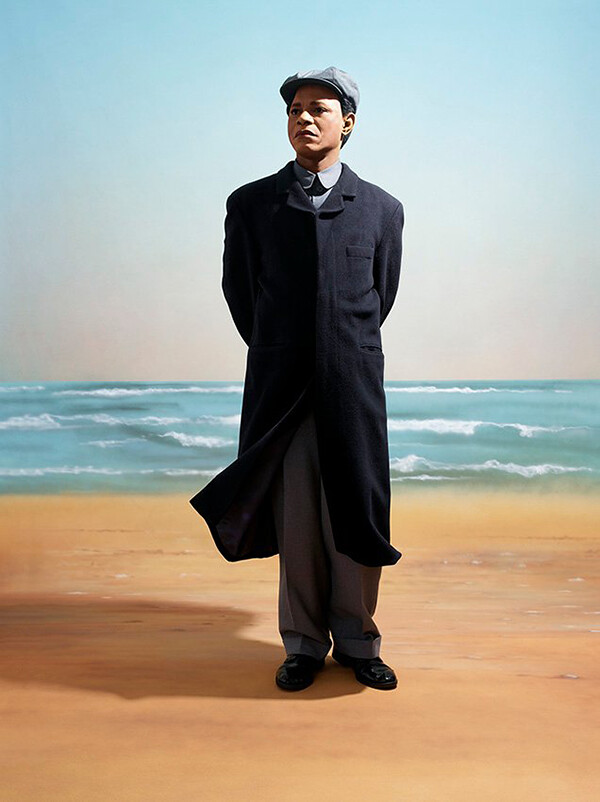

Samuel Fosso, Self-Portrait as Mao Zedong, from the series Emperor of Africa, 2013.

To develop a comparative global framework that accounts for both regional specificities and transnational connections, Jacques Derrida’s theory of “hauntology,” which paradoxically describes presence through absence by combining “haunting” and “ontology,” is uniquely useful.13 It can illuminate the layers of historical resonance in post-Soviet visuality—its multigenerational transferences, digressions, and amnesia. In contrast to research and theory on post-socialist nostalgia, which presumes an explicit acknowledgement of closure (like the fixity of the Sino-Soviet split), hauntology describes the persistence of a past that flies mostly under the radar. This persistence accounts for contemporary art in its different global constellations, finding crucial throughlines in American, Latin American, Eastern European, and African contemporary art. A hauntological approach to post-Soviet visuality ultimately provides a crucial alternatives to both Western-centric modern art history, and a postcolonial discourse that ironically recenters “the West” through negation.

A Missing Hauntological Link: Post-Socialist Resonance in New York14

Yu Hong, Half a Century, 2018.

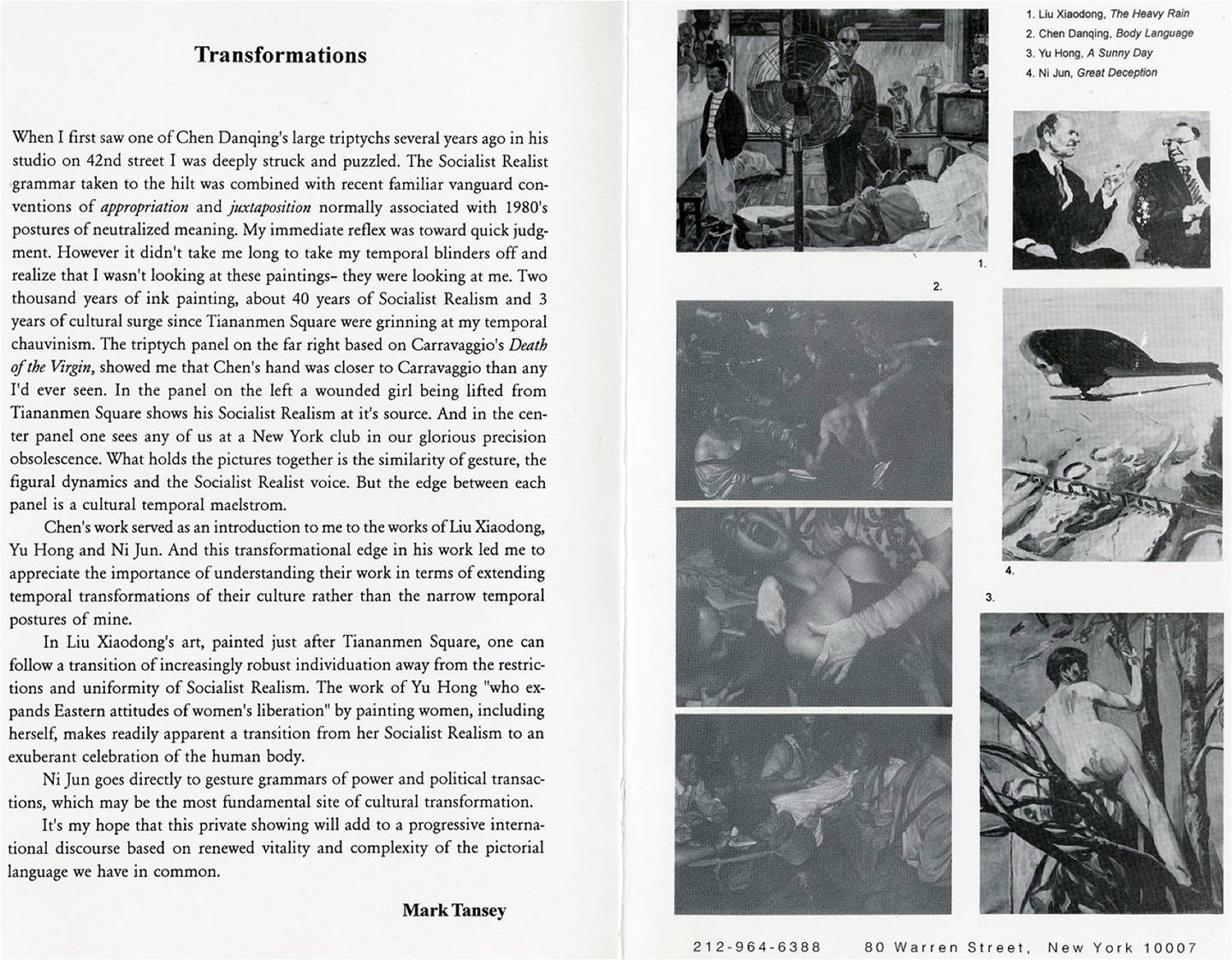

In the early spring of 1994, a private group exhibition titled “Transformations” was held at 80 Warren Street in downtown New York, featuring four Chinese artists who were living in the city at the time: Chen Danqing, Ni Jun, Liu Xiaodong, and Yu Hong. Each had arrived from distinct personal trajectories. Chen Danqing had been living in New York since 1982 on the heels of tremendous recognition within China, after stunning the National Fine Art Exhibition with his Tibetan series. Ni Jun had just finished his MFA at Rutgers University and was curating and publishing to support Chinese artists through his involvement in OIPCA (Organization for the International Promotion of Chinese Artists). It was also Ni Jun who invited Liu Xiaodong and Yu Hong—a precocious artist couple trained at the Central Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing—for a one-year sojourn in New York to participate in Ni’s 1993 exhibition “Red Star Over China.” What was unusual about “Transformations,” however, was that it was curated by Mark Tansey, an American artist who had met the Chinese artists through mutual friends and developed an intense curiosity about their work.

Part of that curiosity stemmed from what Tansey regarded as a retrogressive, passé quality in the work of these Chinese artists. Not only were they primarily painters; they also practiced figuration tinged with “socialist realism,” which at the time was still associated with political propaganda from the recently collapsed Soviet bloc. But Tansey, a painter deeply engaged with realism himself, even if ironically in the interest of conceptual critique, realized that something more complex was at play beyond the immediately striking presence of “skill,” another retrograde characteristic in the Euro-American art world following the explosion of performance and global conceptualism. In the exhibition brochure, Tansey remembered being “struck and puzzled” upon first seeing Chen Danqing’s large triptych Body Language (1993).15 This work juxtaposed three groups of dynamic human figures with strikingly different narrative contents: a virtuoso replica of Caravaggio’s Death of the Virgin; a scene depicting a wounded girl being carried away from Tiananmen Square, alluding to the political upheaval four years earlier; and a glimpse of raunchy intoxication at a typical New York club.

Exhibition brochure of Transformations, edited and published by Mark Tansey, 1994. Works illustrated include Liu Xiaodong’s Heavy Rain, Chen Danqing’s Body Language, Yu Hong’s Sunny Day, and Ni Jun’s Politicians.

Tansey’s observation that “Chen’s hand was closer to Caravaggio than any I’d ever seen” was perceptive: Chen had spent much of his decade in New York intensely studying and emulating old masters at the Metropolitan Museum, relishing in the originals that he had only experienced via copies during his art academy years. Chen had confessed in his own writing and interviews that, soon after arriving in America, he recognized that his entire practice meant very little to the New York art scene, despite astronomical success back home. But rather than give up or change course, he reconciled with the fact that he would not—and could not—become, say, a performance artist. Instead, he lived freely and observantly and at the margins of the art world. At the same time, however, Tansey recognized that the mode of juxtaposition and appropriation in Chen’s triptych belied an engagement with conceptualism—specifically its interest in “neutralized meaning”—while still broadcasting a “socialist-realist voice.” Realizing his own “temporal chauvinism,” Tansey came to appreciate the “renewed vitality and complexity of the pictorial language we have in common.” He wrote of “the importance of understanding [the work of the Chinese artists in the exhibition] in terms of extending temporary transformations of their culture rather than the narrow temporal gestures of mine.”16

Tansey’s ascription of a “socialist-realist voice” to Chen raises a curious point: none of the artists in the “Transformations” exhibition practiced orthodox socialist realism at that time. Their work certainly did not embody socialist realism as characterized by art historians Romy Golan and Nikolas Drosos: “If art was to be realist, it has to take a firm political stance.”17 The paintings by Liu Xiaodong and Yu Hong notably championed exuberant individualism rather than collectivism. Yet certain aesthetic resonances were present.

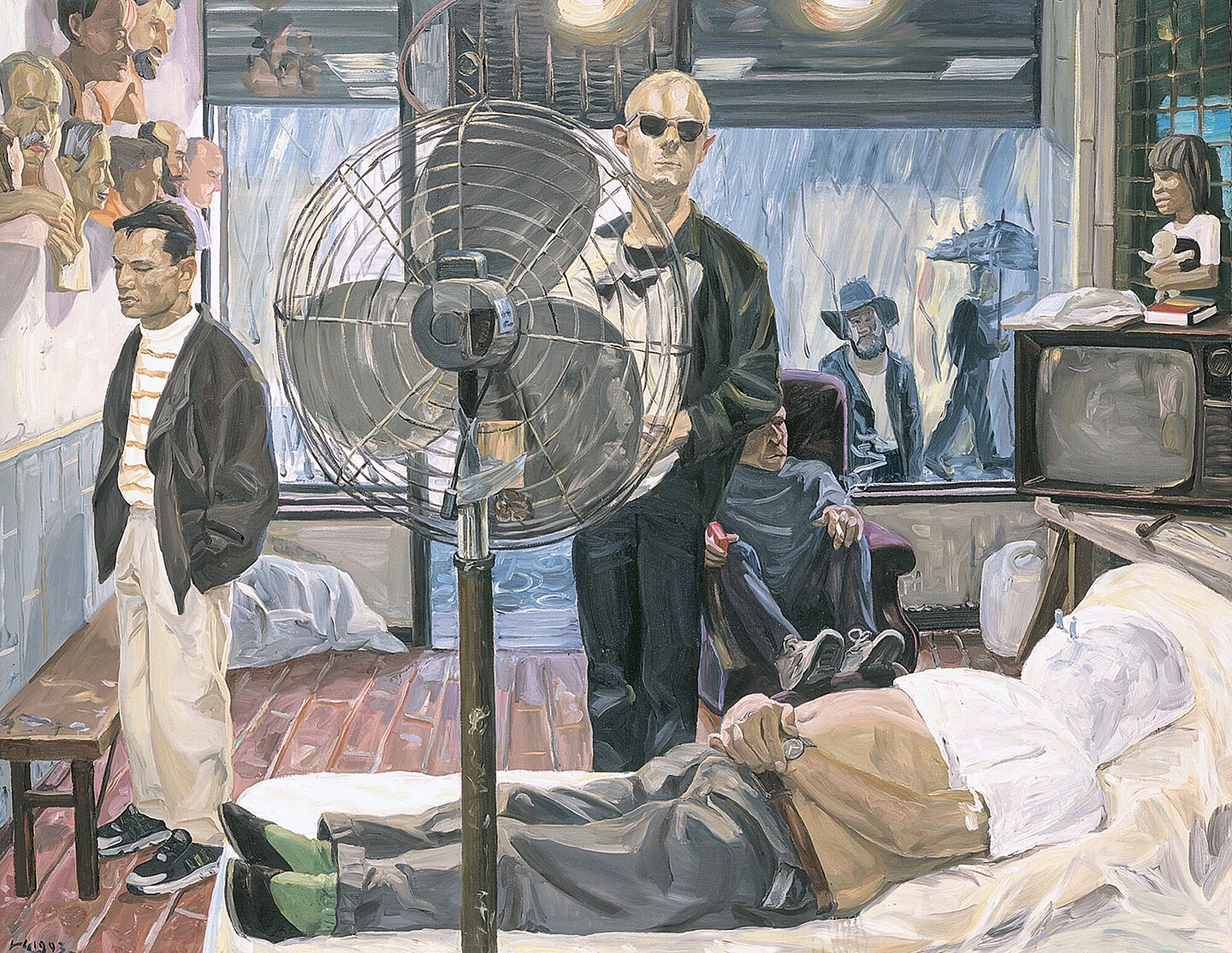

Liu Xiaodong, Heavy Rain, oil painting, 1994.

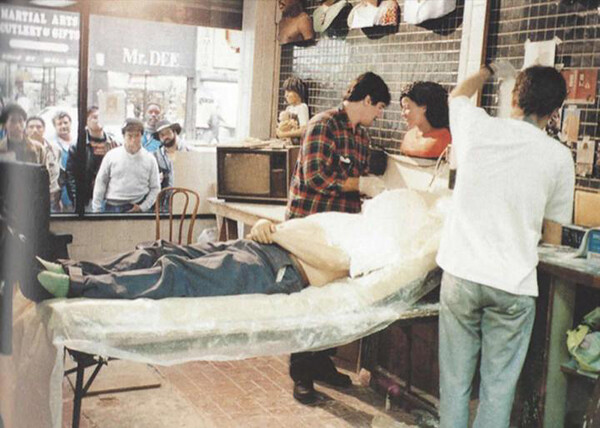

The aesthetico-political paradigm of socialist realism involved nuanced and overlapping ideas of narodnost (people-ness), typichnost (a focus on typical situations in order to explore essential truths), ideinost (ideological content), klassovost (class consciousness), and partiinost (party mindedness).18 But by the 1990s, Chinese artists had completely discarded such remnants of Soviet art pedagogy—that is, if we accept extant art-historical narratives. However, if we look at Liu Xiaodong’s Heavy Rain (1994)—the largest painting he created during his New York stay, when he frequently worked in Chen Danquing’s studio on West 42nd Street—we see the notion of “people-ness” and its attendant focus on representation, identity, and figuration play out expansively. With almost cinematic precision, Liu captures a dramatic moment during a “life-casting” procedure performed by artist John Ahearn on Ai Weiwei in a storefront space downstairs from Chen Danqing’s studio. (Ai is only identifiable by his prominent belly, while his upper body is wrapped in white cloth and plaster.) On the left, the walls are lined with life-cast busts of other New Yorkers. An onlooker peeks through the window from outside, transfixed, despite the downpour. While Liu and Ahearn crossed paths by pure coincidence (Ahearn’s life-casting events were open to almost anyone who walked in), their deeply shared “human interest”—despite using different mediums and formal approaches—is intriguingly clear in Heavy Rain.

By the early 1990s, Ahearn had established a practice of making life-casts—with collaborator Rigoberto Torres—of people in the Bronx, where he lived. The artist considered these casts essentially collaborative, as they drew on “the deeper, idealistic life of the people”; he frequently gifted copy to his sitters.19 The realism with which Ahearn captures his subjects derives from physiognomic imprints, whereas Liu’s realism arrives at its truth through well-honed painterly skill. In his paintings, Liu often reconstructed scenes based on photographs, with their “surplus of meaning.” Indeed, Liu took various photographs of Ahearn’s life-casting of Ai Weiwei—but none identical to the final composition.

Liu Xiaodong’s photograph of the artist John Ahearn creating a plaster cast bust of Ai Weiwei, 1994.

The perceptive readings of Yu Hong’s work by Mark Tansey and Ni Jun—who in 1994 organized a two-person show for Liu and Yu—suggest that her paintings are the most distant from any ideological instrumentalization. Indeed, Yu’s striking series of nude self-portraits, like Sunny Day (1993) (which was reprinted and exhibited in “Transformations” and graced the cover of the brochure for Yu and Liu’s two-person show), could not be further from socialist realism—and its visual rhetoric of feminism—in their carefree, idiosyncratic self-indulgence. Ni noted the surrealist, “MTV-like” vibrancy of these paintings, as well as their subject’s utter disregard for the viewer’s gaze. Yu depicted herself lying relaxed across a wooden floor, stretching next to a tree as if attempting to swim, and sitting on a tree branch, with her round buttock prominently centered in the composition. Neither displaying codified female empowerment nor aggressively challenging “the male gaze”—notions that so often render the female nude a frustratingly fraught site of contestation—Yu liberated her body from any definition but her own, which is arguably an immensely radical gesture.

In a recent interview, Yu recalled that while painting A Sunny Day she was thinking of the towering cotton trees—frequently referred to as “hero trees”—that loom prominently in the background of the classic Chinese revolutionary ballet The Red Detachment of Women. These came to mind, she said, not only due to the enormous cultural prominence of the ballet, but also because her parents were stagecraft professionals.20 The straight trunks with steel-like, shimmering bark in Yu’s painting appear to be almost directly lifted from a production of the ballet. With this imagery activated, one realizes that the artist’s naked self sits rather high (cotton trees typically branch several feet above the ground), afloat in a uniquely post-Soviet, yet still socialist and feminist, space. Revolutionary ballet, after all, was an ideological and aesthetic import from the Soviet Union. This not only made it exempt from suspicions of moral decadence (ironically preserving something authentically “Western”); it also meant that revolutionary ballet was used as a didactic art form during the Cultural Revolution. Yet despite the clear ideological goals it was created to serve, The Red Detachment of Women arguably achieved something genuinely radical through its militarized choreography for female dancers, which glorified—instead of disguised—the immense athletic power of professional ballerinas, perpetuating a narrative in which heroines survive and thrive through their devotion to the communist liberation project (rather than through melodramatic romance).

The way in which “the hero tree” figures liminally yet potently in Yu Hong’s self-fashioning echoes the dynamics through which post-Soviet discourses play out in contemporary art. This makes a hauntological approach not only particularly effective but urgently necessary—not least in exposing historiographic blind spots and intellectual inertia. In the discourse surrounding contemporary Chinese art, modernity is often assumed to connote Westernization, when in fact Chinese modernity is fundamentally indebted to Soviet socialist modernity. No amount of antiauthoritarian posturing by the Chinese avant-garde, which by default denounces Soviet art institutions and pedagogy, can surgically remove this ontology. As Xu Bing—another artist who lived in New York at the time of Tansey’s “Transformation” show—wrote in his 2008 essay “Ignorance as a Kind of Nourishment”:

The eighties saw a great influx of Western thought, followed by its discussion, comprehension, and assimilation. But as far as I was concerned, it was all just another opportunity to mark oneself formally “present.” Once [Maoist thought] has taken residence in your thought patterns, it is difficult for anything else to squeeze itself in.21

Art history, on the other hand, has failed to competently account for the “post-socialist” in postmodernism, not so much as an interpretative framework but as a preexisting and indeed “haunting” condition.

David Alfaro Siqueiros, Proletarian Victim (originally subtitled In Contemporary China), 1933. Collection of the Museum of Modern Art.

It is telling, for instance, that after MoMA’s ambitious 2019 reinstallation of its permanent collection—which was designed to reexamine various trajectories of modernism—modern and contemporary Chinese and Latin American art were still firmly separated, despite having engaged in long, fruitful, and revolutionary conversations throughout the twentieth century, as evinced by MoMA’s own collection. The Mexican muralist David Alfaro Siqueiros, for example, directly acknowledged his indebtedness to the 1930s New Woodcut Movement in China—an anti-imperialist, public-oriented visual campaign characterized by bold, visceral imagery—in works such as Proletarian Victim (1933), which was originally subtitled “In Contemporary China.” Soviet and Mexican artists traveled to China through diplomatic and cultural exchanges starting in the 1950s, participating in a number exhibitions there. The hauntological dimension of post-socialist legacies might just be the missing link that allows us to understand much of postmodern art truly on its own terms, taking account of the inherent contradictions, mediations, and transformations of historical circumstances.

Ni Jun, the last artist to be discussed in Tansey’s “Transformations” brochure, was very active in the early 1990s as both a curator and artist. The works Ni exhibited in Tansey’s exhibition came from his Rutgers MFA thesis series Great Deception (1991). They spoke pointedly to the role of political theater at the turn of the 1990s, taking mass-media images of international politicians and recasting them in a socialist-realist aesthetic—a Warholian gesture, had Warhol known socialist realism. But perhaps he did. One of Ni’s many curatorial projects was the exhibition “Mao 100” (1993), which “celebrated” the great leader’s centennial by gathering contemporary artistic responses to Mao’s legacy. Most of the participating artists appropriated and transformed familiar, iconic, mediated images of Mao. The exhibition also featured several of Warhol’s 1972 Mao prints, which display a profound understanding of repetition as medium, message, and persuasive power. Warhol gravitated towards images of Mao because they were the most reproduced in the world; this was fueled domestically in China by a Mao image cult, and internationally by Nixon’s visit to China in 1972. The exhibition’s accompanying catalogue featured an interview Ni conducted with artist Vitaly Komar, a Soviet émigré who moved to the United States in 1978 with his longtime collaborator Alexey Melamid. The duo socialized with both Tansey and the Chinese artists in the “Transformations” show. In the interview, titled “Mao and Modernism,” Komar claimed:

I don’t believe Andy Warhol was the reason for Mao influencing contemporary Art. We understand all ideas of Socialism in connection with Modernism. When Socialism appeared, it was an idea to destroy old traditions and to build a new world. All modernism is a product of the Socialist idea.22

Curiously enough, later in the same year, MoMA PS1 mounted an exhibition titled “Stalin’s Choice: Soviet Socialist Realism 1932–1956,” which presented Komar, along with other post-Soviet artists such as Ilya Kabakov, as embodying a postmodern/post-socialist critique of the socialist-realist legacy. Yet even a New York Times art critic was perceptive enough to write that,

linked as it was with Hitler’s fascist art, with Communist Chinese art and the art manufactured in Soviet satellites, realism under Stalin may have as much a claim on the cultural identity of this century as high modernism does. What’s interesting to ponder is that while the two—modernism and socialist realism—are usually pitted against each other as opposites, they have more in common than advocates of either would like to admit. Both claimed universality, and both claimed to embody the spirit of social revolution.23

“Stalin’s Choice” operated from a safe historical vantage point—the period just after the collapse of the USSR. Its curatorial premise was that socialist realism and socialist modernity were a thing of the past—curious, quaint subjects that were no longer active or threatening. By contrast, artist-organized exhibitions such as “Transformations” and “Mao 100,” and the unlikely, productive friendships among artists such as Mark Tansey, Chen Danqing, Liu Xiaodong, Yu Hong, Ni Jun, Vitaly Komar, and John Ahearn—whose work together has been largely ignored by art-historical accounts of New York in the late 1980s and early 1990s—suggest much longer and deeper historical frameworks at play, continuously reactivated in ways that are beyond the grasp of current theoretical and art-historical discourse. Ignorance of post-Soviet hauntology will continue to haunt institutional efforts to recognize global modernisms and make deeper sense of the recent resurgence of figuration, representation, and identity politics in the art world. In 1992, Komar and Melamid published an enticing project proposal in Artforum titled “What Is To Be Done with Monumental Propaganda?” They wrote: “We propose neither worship nor annihilation of these [Soviet socialist-realist] monuments, but a creative collaboration with them—to leave them at their sites and transform them, through art, into history lessons.”24 As a prompt, the artists presented a collage in which the letters in “Lenin” inscribed above the entrance to the revolutionary leader’s mausoleum were changed to “Leninism,” a gesture that, in its ironic brilliance, encapsulates the very essence of Soviet hauntology in post-Soviet history.

Chen Danqing, Travels of Ignorance (Guangxi Normal University, 2014).

Elizabeth McGuire, Red at Heart: How Chinese Communists Fell in Love with the Russian Revolution (Oxford University Press, 2018).

Though Repin was born in what is now Ukraine’s Kharkiv region, he remains a key reference in the Russian art-historical canon.

Zhang Bei, “Seventy Years of the People’s Education Press,” The Paper, December 2, 2020 → (in Chinese). Ping Luqing charted, beginning in 1921, the growing discussion of Barge Haulers in Chinese publications and artistic, political, and intellectual circles. See Luqing, Meishu jiaoyu yanjiu (Art research study), no. 2 (2014): 49.

Wu Dazhi, “Barge Haulers on the Volga River,” originally published in Wenyi xuexi (Literary and art studies), no. 7 (1956). All translations are my own unless otherwise specified.

I’m indebted to Anton Vidokle for sharing scholar Svitlana Shiells’s work on Repin’s Ukrainian heritage.

The idea that writers are “engineers of the human soul,” first articulated by Stalin, permeates the Chinese Communist Party’s education ideology up to the present day. It is very much alive in Xi Jinping’s rhetoric.

Terry Martin, The Affirmative Action Empire: Nations and Nationalism in the Soviet Union, 1923–1939 (Cornell University Press, 2001).

McGuire, Red at Heart, 5.

Deborah A. Kaple, Dream of A Red Factory: The Legacy of High Stalinism in China (University Press, 1994), 5.

Boris Groys, “The Cold War between the Medium and the Message: Western Modernism vs. Socialist Realism,” e-flux journal, no. 104 (November 2019) →.

David Joselit, Heritage and Debt: Art in Globalization (MIT Press, 2020).

Jacques Derrida, Specters of Marx (Routledge, 2006).

This section has been largely adapted from an essay with the same title written for the series Delayed Boundaries in the Wake of Media Expansion, published by Taikang Space, Beijing. Initially published in Chinese on Taikang Space’s WeChat platform, the series was published as a bilingual anthology in 2022.

Mark Tansey, “Transformations,” exhibition brochure, 1994.

Tansey, “Transformations.”

Romy Golan and Nikolas Drosos, “Realisms as International Style,” in Postwar: Art between the Pacific and the Atlantic, 1945–1965 (Haus der Kunst, 2016), 443.

Golan and Drosos, “Realisms as International Style,” 443.

Jane Kramer, “Whose Art Is It?” The New Yorker, December 21, 1992 →.

Interview with the author, August 2020.

Xu Bing, “Ignorance as a Kind of Nourishment,” trans. Jesse Robert Coffino and Vivian Xu, 2008 →.

Vitaly Komar, interviewed by Ni Jun, “Mao 100,” exhibition brochure, 1993.

Michael Kimmelman, “Stalin’s Painters: In Service of the Sacred,” New York Times, December 10, 1993 →.

Komar and Melamid, “What Is To Be Done with Monumental Propaganda?” Artforum, May 1992 →.