1.

In our society, the dominant dispositive regulating the treatment of past wrongs is juridical.1 The court is the arena, defined according to formalized rules, for the individual attribution of responsibility, the disclosure of forensic knowledge, the public hearing of witnesses and defendants, the resolution of a dispute about the legal and factual situation, a judgment made in the name of society as a whole, and for consequences introduced in the form of a sanction enforced by coercive state power. Can or should radical political movements in general and critical artistic interventions in particular also make use of the form of the court? Is it a suitable medium to scandalize social mechanisms of oppression or exclusion, to democratize knowledge, to empower marginalized groups, to assign political responsibilities, to make judgments about power and the powerful, and finally, to struggle for appropriate consequences? Can and should such movements take over the form of the court, especially given that the judicial system in particular is part of a state apparatus that is based on the constant reproduction of violence? This question is of course to be asked in the context of the much larger question of which stance to take with respect to bourgeois institutions in general: Is there something to be rescued, despite their formalistic, bureaucratic, claustrophobic, cruel, cold, and merciless modes of operation?

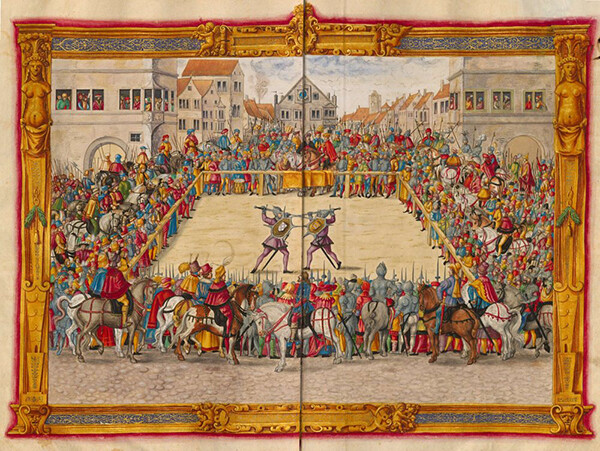

Judicial duel between Marshal Wilhelm von Dornsberg and Theodor Haschenacker in the Augsburg wine market (1409). Dornsberg’s sword broke early in the duel, but he succeeded to kill Haschenacker with this gentleman’s own sword. Their shields were kept in St. Leonard’s Church outside of Augsburg until it was destroyed in 1542. License: Public Domain.

The use of tribunals by artistic and political groups has a long tradition: the surrealists’ experiments with the court form to articulate criticism and self-criticism in the 1930s; the well-known tribunal initiated by Bertrand Russel against war crimes in Vietnam (1966–67); the “Foucault Tribunal” against psychiatric institutions organized by the Irrenoffensive (Lunatic Offensive) in Berlin in 1998; the Women’s International War Crimes Tribunal on Japan’s Military Sexual Slavery in Tokyo (2000); the World Tribunal on Iraq organized by NGOs and human rights groups (2003–5); the Refugee Tribunal against the Federal Republic of Germany (2013); the Congo Tribunal (2013/15) orchestrated by Swiss director Milo Rau; the Capitalism Tribunal (2015) launched by the Berlin-based artists’ group Haus Bartleby; the Court for Intergenerational Climate Crimes in Amsterdam (2021) staged by Jonas Staal and Radha d’Souza; and countless other smaller, local tribunals. All of these tribunals were designed to hold the powerful accountable for what might not legally be seen as a “crime” but did grave harm to humanity.

On the one hand, the attractiveness of proto-judicial formats, such as the tribunal, for political movements is obvious: adopting established forms of accusation, witness narration, attribution of responsibility, and pronouncement of judgment promises publicity and thus political clout. The tribunal bundles the subjective experiences of those affected and makes their general political relevance intelligible. The indictment denaturalizes injustice by naming liable persons or entities that can be reproached for it. By presenting evidence and investigative findings, tribunals produce counter-knowledge and agitate for political change. By lending public attention to witnesses, they make marginalized voices heard. Finally, the symbolic condemnation of injustice is essential to symbolically reintegrate into the community the victim whose dignity was attacked.

On the other hand, considerable objections have been raised against the judicial form. Indictment, as prosecution, ascribes responsibility for a wrong in the form of “guilt” or “liability” to individual actors, thereby losing sight of broader social and political contexts. Also, the sheer magnitude of social injustice often defies the logic of equivalence in legal sentencing. For Hannah Arendt, one consequence of the crimes of twentieth-century totalitarianism is that not only can they not be redressed, they cannot even be charged in the form of a personal attribution of responsibility: “The gas chambers of the Third Reich and the concentration camps of the Soviet Union,” she writes, “have interrupted the continuity of occidental history because no one can seriously take responsibility for them and nobody can seriously be made responsible for them.”2 This impossibility of the individual assumption of responsibility thwarts the juridical logic of judgment. For Arendt, Adolf Eichmann therefore deserved the death penalty not because this would be appropriate to the deed—nothing is appropriate to the deed—but because no one could be expected to live together with him in this world anymore. However, this is not a legal but an ontological argument.

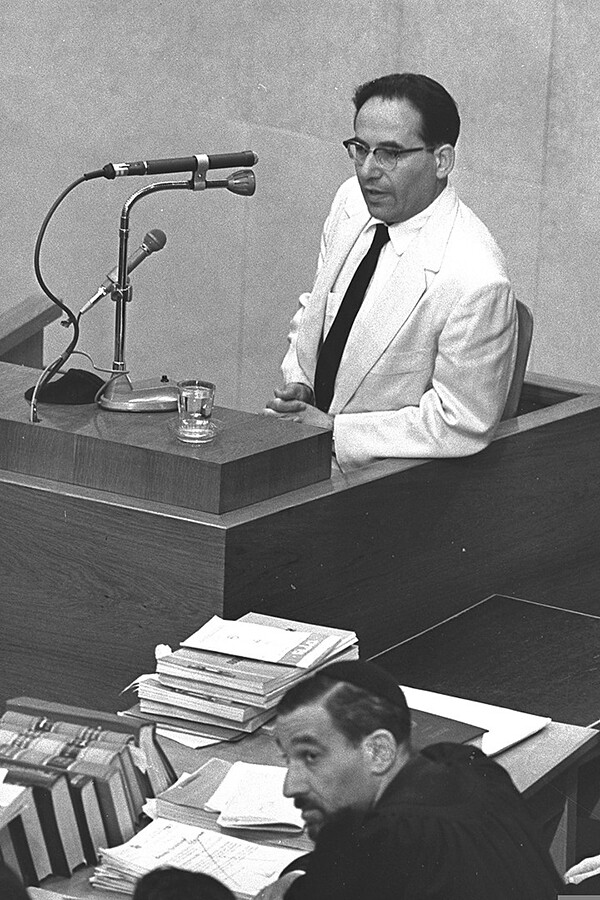

Auschwitz trials of 1963–65 against the SS members in Frankfurt am Main. Source: Encyclopædia Britannica.

Testimony is not only enabled in court, but also formalized, directed, channeled, and thus limited by it. Testimony, according to literary critic Shoshana Felman, is the translation of trauma into “legal consciousness.”3 Testimony that is valid in court must follow a fixed set of rules: it is subject to certain requirements of coherence and stringency, it must be limited to a thematic framework and omit other aspects, and it must represent the witness as a sane and credible subject capable of correctly recalling and truthfully reflecting the facts testified to. Above all, the witness must prove themself as a knowing but disembodied being who can enter into a relationship of protective distance to what they have experienced or seen. In turn, the testimony can destroy this distance by re-confronting the witness with the injustice and thus re-traumatizing them. For Felman, art in particular serves as a placeholder for another, nonjuridical form of memory. Art can play this role because it expresses its own non-referentiality. In her book The Juridical Unconsciousness, Felman writes: “Law is a language of abbreviation, of limitation and totalization. Art is a language of infinity and of the irreducibility of fragments, a language of embodiment, of incarnation, and of embodied incantation or endless rhythmic repetition.”4 Bringing justice towards victims is only made possible in keeping open this genuinely artistic, precisely not juridical or proto-juridical form of testimony.

The juridical judgment, as verdict, resists simple adoption in the service of transformative justice. It enforces (already according to its grammatical form) a dissolution of all ambivalences and ambiguities of the facts of the case; the judgment presents itself as a definitive conclusion of the unfolding of the trial. At the same time, in court proceedings, all but one (or in the case of a jury, a few) are deprived of the competence to judge; only the judge or the jury can finally and conclusively assess the facts of the case. The professionalized status of those making judgments also always predetermines the content of these judgments. In artistic or activist tribunals, this role is usually assumed by publicly recognized intellectuals who, socioculturally speaking, come from the same class background as the jurists of bourgeois legal proceedings.

2.

In June 1972, the journal Les Temps Modernes published a debate between Michel Foucault and two Maoists on the question of popular tribunals. While Foucault opposes the popular adoption of the tribunal because he considers it an imitation of the bourgeois court form, the two Maoists, who here go by the aliases Victor and Gilles, on the other hand point to the important role that indictments and convictions play in popular courts in Maoist China. Both sides agree that the bourgeois judiciary is a class justice system from which actual justice cannot be expected. The oppressive nature of the judiciary is evident to the people, which is why courthouses are often the first to go up in flames during uprisings and revolutions. There is a disagreement, however, over whether the oppressive character of the court is determined by its content or its form.

Russell Tribunal in Stockholm, 1967. Nine-year-old Do Van Ngoc exhibits injuries from napalm in Vietnam. License: Public Domain.

For the Maoists, the content is decisive: A revolutionary court is quite different from a bourgeois court. Not only is it run by different historical actors, but it is also situated in a different socioeconomic context and therefore fulfills a very different function than the bourgeois court. According to the Maoists, the essential function of popular tribunals is to publicize norms. Public hearings express new ideals and values and make them known. This way, the general interest of the revolution asserts itself over the particular interests of individuals. The jurisdictions of the popular courts have thus both an educational and a disciplinary character. On the one hand, they ensure that the actions taken against the former oppressors are consistent with the ideology of the revolution and do not simply represent a particularistic “settling of accounts.”5 In this way, the publicity of the trial allows the entire populace to participate in taking “inventory of all the extortions, of all the suffering caused by the enemy,” and thus to educate themselves in the new normative order.6 On the other hand, the revolution, at least in the first phase, still needs a “revolutionary state apparatus” to discipline individuals and unite them into a movement.7 The tribunal form of popular justice conveys to individuals that the ideology of the revolution is henceforth binding and that the pursuit of their individual particular interests will be sanctioned if necessary. Remarkably, Victor and Gilles insist above all on the moderating effect of the tribunal form: a public trial ensures that the people’s spontaneous acts of revenge against their oppressors do not turn arbitrary or exuberant.

For Foucault, on the contrary, the tribunal is essentially determined by its form. According to his analysis, the tribunal historically served primarily to divide the proletariat from the non-proletarianized plebs, i.e., the lumpenproletariat, by staging criminality not as a legitimate form of revolt but as a moral transgression, thereby simultaneously distracting attention from the much greater crimes of the capitalists. The court accomplishes this divisive function primarily through its specific aesthetic arrangement. For Foucault, there is always a table at the center of this aesthetic setting. The table imposes a triangulated normative geometry on the litigants. The parties do not face each other head-on, but are mediated by a third position, the judge. This spatial arrangement entails three specific problems for Foucault. First, alienation. The competence to do justice is expropriated from the parties by delegating the administration of justice to an external entity, which then confronts them heteronomously and “imperiously.” Second, ideology. The court asserts a basic neutrality toward the parties, that is, a disengagement and impartiality toward the subject matter of the dispute. Because of this disengagement, judgment must be determined according to specific truth procedures and decided according to conventional but naturalized norms. At the same time, by claiming that only the court, and not the parties, is in possession of this objective view, it usually allows only certain experts or intellectuals access to the bench. Finally, thirdly, the coercive or command character of the judgment. The court’s adjudication has not only an expressive function (to communicate what is just), but a direct performative effect (to implement or enforce the judgment). In a triangulated geometry, the violence to which the tribunal licenses itself is never directed only against the enemy, but always tends to turn against others as well; Foucault points to the popular tribunals of the French Revolution, which used their instruments of violence only to a small degree against the representatives of the ancien régime and soon began to try galley convicts and prostitutes as well.

Taken together, the tribunal, embodied in the installation of a table, serves not to implement genuine popular justice but, on the contrary, amounts to its first “deformation”: it domesticates the people’s desire for justice by pacifying the agonal struggle between adversaries and suspending their fundamental differences. The aesthetic arrangement of the tribunal, Foucault concludes, fosters the reappearance of the “embryonic, albeit fragile form of a state apparatus.”8

In the conversation with the Maoists, Foucault reveals his own political sympathies more openly than in other texts. For Foucault, the historical alternative to the tribunal form was the direct, unmediated actions of popular justice: spontaneous revenge or direct action, such as the execution of punitive or educative measures by the people. Popular justice is opposed to the tribunal form in all three respects mentioned above. Instead of the triangle of the tribunal, in popular justice there is a line, a direct horizontal antagonism of the adversaries: “In the case of popular justice you do not have three elements, you have the masses and their enemies.”9 Gilles Deleuze, in his programmatic text “To Have Done with Judgment,” will make a similar point, when he contrasts horizontal combat between two opponents who mutually affect each other’s bodies with the “doctrine of judgment” which inscribes the debts of the parties in an autonomous book and thus condemns them to endless submission.10 Popular justice actualizes unmediated forms of jurisprudence when, instead of simulating an abstract idea of justice that claims objectivity, it relies only on its experience of injury and damage, thus admitting its situated and partisan character from the outset. And finally, the legal consequences of this form of justice are also anti-juridical; instead of entrusting a bureaucratic state apparatus with the enforcement of the decisions, the people “simply carry them out.”11 While the court is mediated, popular justice is immediate; while the court claims neutrality and impartiality, popular justice is experience-based and partisan; while the court enforces its decisions with state coercion, popular justice is based on direct execution by the people themselves.

While the Maoists consider the content of the tribunal (its subjects and subject matter) to be crucial, for Foucault its form is the ultimate determinant—that is, the aesthetic arrangement on which it is based. In this conversation, the two positions remain diametrically opposed to each other. From a more Hegelian perspective, which conceives of form and content as mutually conditioned and conditioning, both sides appear truncated. The absolutization of the content side fails to recognize that even the content of a thing is also determined by its form; form enables and limits what a thing can be. The absolutization of the form side, on the other hand, fails to recognize that form itself is the result of a historical, that is, content-based convention that can be changed. (A mathematical truth cannot be expressed in form of a novel—unless we fundamentally change what we understand as “mathematics” and what we understand as “novel”).

The Maoists thus underestimate the historical gravitational force of the judicial form, which already carries with it a tendency toward statification in the underlying spatial division. Foucault, on the other hand, fails to recognize the statification that also exists in the unmediated directness of the relation of “the masses against their enemies.” It falls to the Maoist Victor to point out that the people can also be manipulated, that the authenticity of popular justice presupposed by Foucault is misleading. He cites the example of the women who had their hair shaved off after the liberation of France from Nazism because they had slept with Germans. While the three men agree that it is all well and good to “entertain the people” by shaving these women bald who, after all, were “offensive to the deepest, bodily, sense of patriotic feeling,” Victor points out that this also diverts attention from the actual collaborators, i.e., capital.12 Foucault thus discredits the form of the tribunal, but at the same time holds on to the traditional nationalistic notion of a people imagined as authentic, homogeneous, and without internal differences—a notion that reproduces its own power relations, exclusions, and violence.

Yehiel De-Nur testifies at the trial of Adolf Eichmann in 1961. License: Public Domain.

One way out of the mistakes that both sides make by absolutizing their respective position (form and content, respectively) is to understand the mediatedness of the tribunal’s form and content. When Victor calls for bending the stick (of violence) “in the other direction,” Foucault succinctly counters him that he deems it essential that the “stick be broken.”13 A dialectical mediation of the two strategies would recognize that one can break the stick only by turning it to the other direction—or that one can turn it to the other direction only by breaking it. For example: those who accuse the state of crime, capital of theft, or psychiatry of madness take over the bourgeois categories, turn them around, and thus push them beyond themselves.

What does this mean for the question of the usefulness of tribunals for contemporary political or artistic activism? Toward the end of their argument, Foucault and the Maoists come up with an example of a political tribunal that had formed two years earlier, in 1970, in the industrial town of Lens in northern France.14 In a coal mine, a gas explosion claimed the lives of sixteen miners. When the public prosecutor refused to investigate the state mine operator for sharing responsibility for the unsafe working conditions, members of the Maoist group Gauche Proletarienne attacked the state mine operator’s headquarters with Molotov cocktails. Unlike those responsible for the explosion, those responsible for the attack were immediately arrested and charged. Maoist organizations responded to this discrepancy by organizing a high-profile “People’s Tribunal” in the Lens town hall to address working conditions in the coal industry. The tribunal imitated the forms of bourgeois court proceedings: an indictment was read, witnesses questioned, evidence presented, a jury summoned, and a verdict pronounced. The Lens People’s Tribunal owed its media attention primarily to the prominence of its chief prosecutor: it was no one less than Jean-Paul Sartre, already familiar with the form of the tribunal through his role as executive president at the 1967 Russell Tribunal, who in his closing statement described the explosion at the mine as an act of “intentional manslaughter, if not murder.” The verdict follows Sartre’s reasoning: the “Boss-State,” represented by the mine’s managers and engineers, is found “guilty” of the death of the sixteen miners.

In her reading of the discussion between Foucault and the Maoists, media scholar Cornelia Vismann starkly contrasts the form of the tribunal with that of the court. The form of the tribunal, such as the one used in the People’s Tribunal of Lens, according to this reading is completely freed from the three characteristics that Foucault elaborated about the court, because the tribunal admits to its partiality, partisanship, and lack of state-enforced consequences. Vismann rightly points out that the judgment in the tribunal is a foregone conclusion, which is why it could not maintain the judicial fiction of neutrality and impartiality anyway. She therefore without hesitation assigns the tribunal to the side of popular justice, which functions according to completely different rules than the court.15 This interpretation, however, ignores the ambivalence that Foucault expresses with regard to the tribunal of Lens. Such tribunals, he concedes, can play a role in the struggle against established powers precisely as long as they exercise primarily an “informational power”: the epistemic monopoly of the state is broken by the fact that a tribunal independently determines and disseminates a truth. However, the tribunal immediately loses this role as soon as it rises to the status of “counter-justice” by declaring a person guilty, seizing them, and forcing their punishment—then the “counter” of “counter-justice” would be erased and the tribunal would simply be “taking the place of the judicial system.”16 Vismann passes over the fact that, after all, even in tribunals there is a table, which for Foucault is the interior-architectural nucleus of judicial asymmetry. The chief prosecutor Sartre, on the other hand, lacks any understanding for such criticism; in an interview published in 1973, he accuses the philosophy professor Foucault of a slightly adolescent left-wing radicalism: “I can’t see that whether people are sitting behind a table or not can cause any harm.”17 For Victor (the cover name of Benny Lévy, who would later become Sartre’s private secretary), then, it is precisely the judgment pronounced “in the name of the people” that seizes the minds of the masses and can thus become a real material power. The dispute between Foucault and the Maoists thus comes to a head on the question of the verdict: the manner in which the trial is concluded reveals whether the popular revolt reterritorializes itself into a law-positing power, or whether it keeps the door open for other forms of justice and jurisprudence.

3.

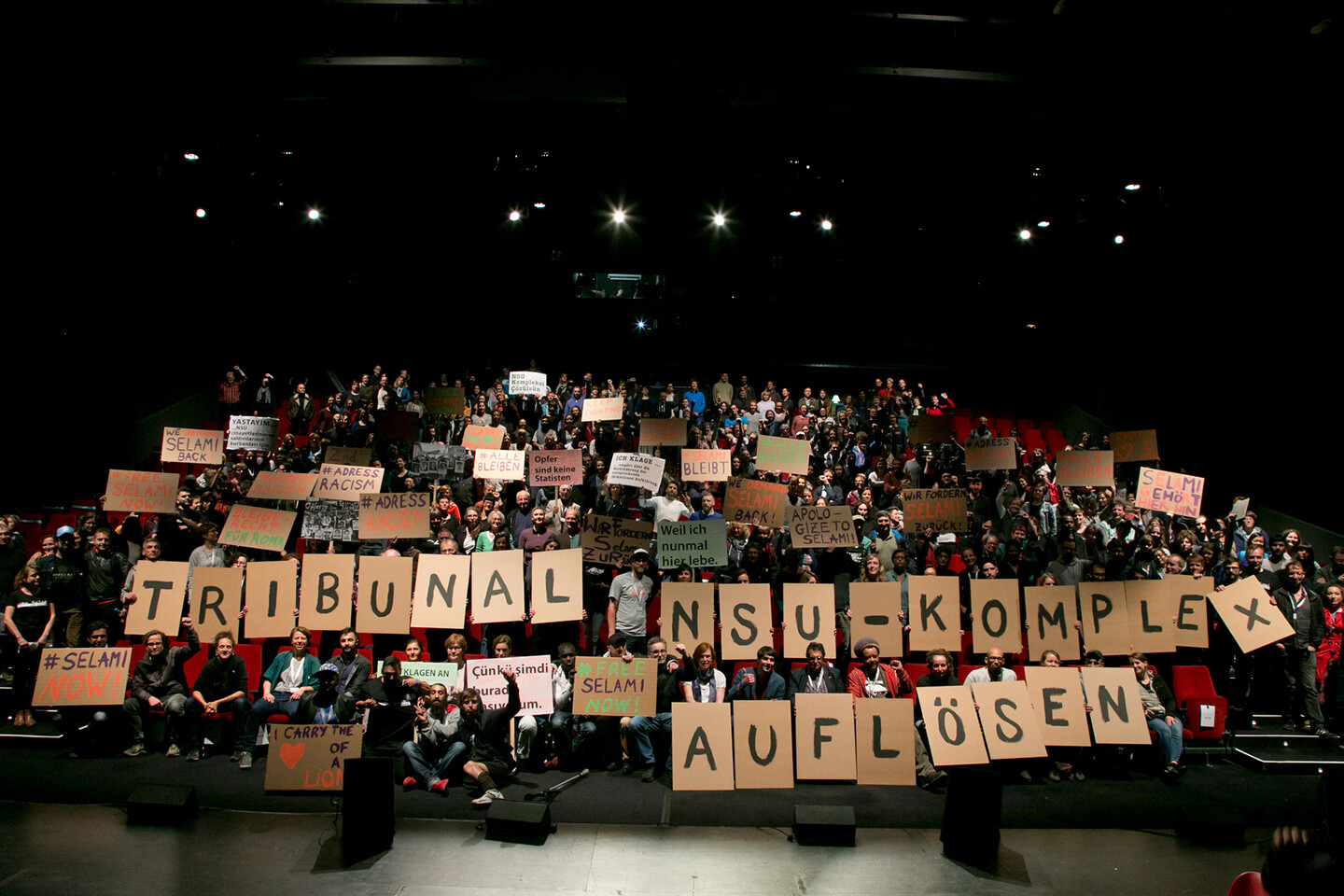

Tribunal NSU-Komplex Auflösen (Tribunal to Dissolve the NSU Complex) is a Germany-wide alliance of local initiatives that was founded in 2014 to create a structure for investigating the political and social background of the terror of the so called National Socialist Underground, an extreme right-wing terrorist group that killed nine people with migrant backgrounds between 2000 and 2006.18 While all kinds of anti-racist groups and individuals are involved in the alliance, it assigns a special role to the victims of the NSU terror and their relatives. As one of numerous political activities—which include renaming streets, developing alternative forms of commemoration, and participating in demonstrations —the alliance also organized three tribunals in art and theater spaces: the tribunal “NSU-Komplex Auflösen” at the Schauspielhaus Cologne in 2017, the tribunal “Wir Müssen Reden Hadi” (We Have to Talk, Hadi) at the Kunsthalle Mannheim in 2018, and most recently the tribunal “Solidarität Verteidigen” (Defending Solidarity) at various sociocultural venues in Chemnitz and Zwickau in 2019.19

Tribunal NSU-Komplex. Photo: Dörthe Boxberg.

The NSU tribunals are not, as in the examples of popular justice mentioned by Foucault, about direct action by the people against their enemies. Rather, the tribunals establish aesthetic instances of mediation in which the facts under trial can be thematized, highlighted, and staged. They thus create a distance and alienation from the spontaneous sense of justice of both the survivors as well as the society surrounding them. Instead of thinking of “the people” as a homogeneous unity whose authentic interests can spontaneously turn against their antagonists, this concept also takes into account the heterogeneity and conflictuality within not only “the people,” but also amongst victims and relatives themselves. At the same time, these tribunals bear the formal characteristics that Foucault ascribes to popular justice as opposed to the court. The truth-telling organized within them is decidedly counter-state: the state’s modes of legislation, execution, and jurisdiction are explicitly identified not as antidotes to, but as enabling conditions for, right-wing terror. The tribunals also lack the problematic hallmarks of the court: they are admittedly situated, engaged, and do not call for state enforcement. The alliance thus seems to have found a way to open up the concept of the tribunal for “reuse” for radically transformative politics through a radical change in both content and form.

Like the Lens tribunal, the NSU tribunals are counter-trials. They comment on, criticize, and repudiate the official criminal proceedings against the NSU murderers and their supporters. The “counter” does not only refer to the contents of the proceedings, such as the selection of the defendants, individual witness testimonies, or the sentences imposed. Rather, the NSU tribunals also distance themselves from bourgeois criminal trials in terms of form. Unlike many other artistic or activist tribunals, the NSU tribunals do not imitate the procedures and role assignments of a bourgeois court trial. The only remaining judicial moment is the formulation of an indictment. However, this indictment is not filed by an advocatory prosecutor but by the victims and relatives themselves, whereby the indictment and the testimony become one and the same.20 Bearing witness means to accuse. The framing of this indictment implies a post- or anti-juridical gesture. The corresponding program item at the Cologne tribunal is called “Klage und Anklage” (complaint/lament and accusation/indictment), whereby the aspect of assigning responsibility is supplemented by the aspects of mourning, grieving, and demanding. At the NSU tribunals there are no defense attorneys or lawyers, no judges or juries, no closing arguments, no pronouncements of verdict. In accordance with the goal of primarily investigating the social and political background of the NSU complex, the tribunals essentially consist of political talks and activist workshops.

For people’s tribunals to retain their place in the anti-judicial struggle, it is crucial that they refrain from pronouncing an enforceable verdict. This is also the case with the NSU tribunals. The serial character of the tribunals alone, which took place at several locations and can in principle be repeated again and again, points to the inconclusive character of this form of trial. But the initiative itself also points out the impossibility of a verdict:

We indict, but we do not pronounce a verdict. Because we cannot and because we do not want to. We cannot pass a verdict because investigations are blocked, investigations are denied, evidence is destroyed or hidden … We do not want to render a verdict because we believe that society must draw consequences from the indictment. The responsibility lies with all who want to see the anti-democratic collusion—the collusion of secret services and neo-Nazis—ended and who strive for a society without racism.21

The lack of a verdict in the proceedings is thus neither the result of a practical difficulty—not having the means to conduct an adequate investigation—nor a lack of desire for consequences. Above all, the renunciation of verdict within the staging of the tribunal does not at the same time mean the renunciation of moral or political judgment on the part of those involved. On the contrary, the NSU tribunals express here that the enabling conditions of justice lie precisely in the suspension of their proto-juridical form.

4.

For Adorno, the trial of those responsible for Nazi crimes is simultaneously necessary and impossible. “The historic basis of [this] aporia,” he writes in Negative Dialectics,

is that in Germany the anti-Fascist revolution failed, or rather, that in 1944 there was no revolutionary mass movement. The contradiction of teaching empirical determinism and yet convicting the normal monsters (Normalungetüme)—one should perhaps turn them loose after that—cannot be settled by superior logic. A justice that has been reflected upon theoretically ought not to shy away from this contradiction.22

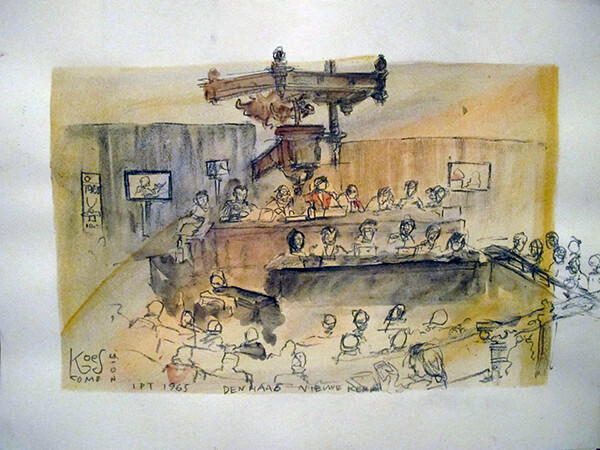

The International People’s Tribunal for 1965 and the Indonesian Genocide, The Hague, 2015.

The ambiguity of judicial justice is the result of a failure of society at large: Because we have refrained from realizing justice directly in the social realm (as in revolution), it is now delegated and concentrated in the arena of judicial procedure. But if monstrosities are themselves normal, then they cannot be evaluated by standards of normality. Here, Adorno formulates a claim for “justice that has been reflected upon theoretically,” namely: not to “shy away from” this insolvable contradiction. And he also hints—albeit very cautiously, in parenthesis—at what this might mean in practical terms for such justice: “One should perhaps turn them loose.”

What is decisive about this option is not the prospect of waiving sanctions for Nazi murderers, but the relativization of the certainty of judgment: perhaps. (After all, one paragraph before, Adorno considers shooting torturers on the spot “more moral” than putting them on trial.)23 The “perhaps” expresses that neither option really produces justice. Rather, a just proceeding is one that knows about the limits of what can be accomplished by it. Adorno tells us nothing about the concrete aesthetic form of what he calls “justice that has been reflected upon theoretically.” But if the aporia that he describes, and that also comes to the fore in Foucault’s dispute with the Maoists, has a “historic basis,” then it can also be addressed historically and, at best, overcome. This is done by revoking the court’s claim to sole judgment and thus reopening society itself as the arena of justice.

Should artists use the court form? Tribunal NSU-Komplex Auflösen shows how the form and content of tribunalism can be put in tension in such a way that makes it reusable as an aesthetic medium of transformative politics. The form changes when the content changes: when other plaintiffs speak, and other facts are negotiated. At the same time, the content changes when the form changes: alternative settings allow for, invite, and produce other voices and other demands. The result is an arrangement that remains on the threshold of its own suspension—because its juridicism is only the representational format of its own limit. “We call upon the public,” reads the Tribunal NSU indictment, “to continue this indictment, to stand up for further investigation and to formulate demands. In this sense, our indictment is not to be understood as legal, but as political. It is an intervention that must be supported by the many. Our indictment belongs to you.”24 This is the Tribunal’s verdict: that the actual trial will take place elsewhere.

See Daniel Loick, Juridismus: Konturen einer kritischen Theorie des Rechts (Suhrkamp 2017).

Hannah Arendt, Elemente und Ursprünge totaler Herrschaft (Piper 2008), 946. Translated by the author. This sentence is missing in the English edition of Arendt’s book.

Shoshana Felman, The Juridical Unconsciousness: Trials and Traumas in the 20th Century (Harvard University Press 2002), 162.

Felman, Juridical Unconsciousness, 153.

Michel Foucault, “On Popular Justice: A Discussion with Maoists,” trans. John Mepham, Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings 1972–1977 (Pantheon Books 1980), 4.

Foucault, “On Popular Justice,” 12.

Foucault, “On Popular Justice,” 12.

Foucault, “On Popular Justice,” 2.

Foucault, “On Popular Justice,” 9.

Gilles Deleuze, “To Have Done With Judgment,” trans. Daniel W. Smith and Michael A. Greco, Essays Critical and Clinical (Verso 1998), 128.

Foucault, “On Popular Justice,” 9.

Foucault, “On Popular Justice,” 9.

Foucault, “On Popular Justice,” 32.

On this, see Pascal Marichalar, Gerald Markowitz, and David Rosner, “Sartre as Prosecutor of Occupational Murder: Notes from a People’s Tribunal in a French Mine (1970),” International Labor and Working-Class History, no. 99 (2021).

Cornelia Vismann, Medien der Rechtsprechung (Fischer 2011), 146–83.

Foucault, “On Popular Justice,” 34.

Cited in Didier Eribon, Michel Foucault, trans. Betsy Wing (Harvard University Press 1991), 247.

See tribunal’s website →.

For an extensive description of the NSU tribunals, see Madlyn Sauer, Wir klagen an! NSU-Tribunale als Praxis zwischen Kunst, Recht und Politik (Unrast, 2022).

It is noteworthy that this form of prosecution is also based on non-police-based forms of investigation. Tribunal NSU-Komplex Auflösen commissioned the British group Forensic Architecture to investigate the murder of Halit Yozgat in Kassel in 2006. In its work, Forensic Architecture arrived at results that, contrary to the official version, strongly suggest the involvement of Andreas Temme, a member of the Hessian Secret Service (Verfassungsschutz). See the final report, 77sqm_9:26min →.

Lückenlos e.V., Tribunale NSU Komplex auflösen (self-published 2020), 77. Translated by the author.

Theodor W. Adorno, Negative Dialectics, trans. E. B. Ashton (Routledge 1973), 287. Translation slightly modified.

Adorno, Negative Dialectics, 286.

Lückenlos e.V., Tribunale NSU Komplex auflösen, 293.

This text is based on a talk given at the Symposium “Tribunalism: The Case for Art,” organized by Susanne Leeb and Clemens Krümmel at the University of Lüneburg in November 2021. A longer German version will appear in the Zeitschrift für Ästhetik und Allgemeine Kunstwissenschaft later this year. I owe many insights to the work of Susanne Leeb, Madlyn Sauer, and Ludger Schwarte.