Art history has failed to competently account for the “post-socialist” in postmodernism, not so much as an interpretative framework but as a preexisting and indeed “haunting” condition. The hauntological dimension of post-socialist legacies might just be the missing link that allows us to understand much of postmodern art truly on its own terms, taking account of the inherent contradictions, mediations, and transformations of historical circumstances.

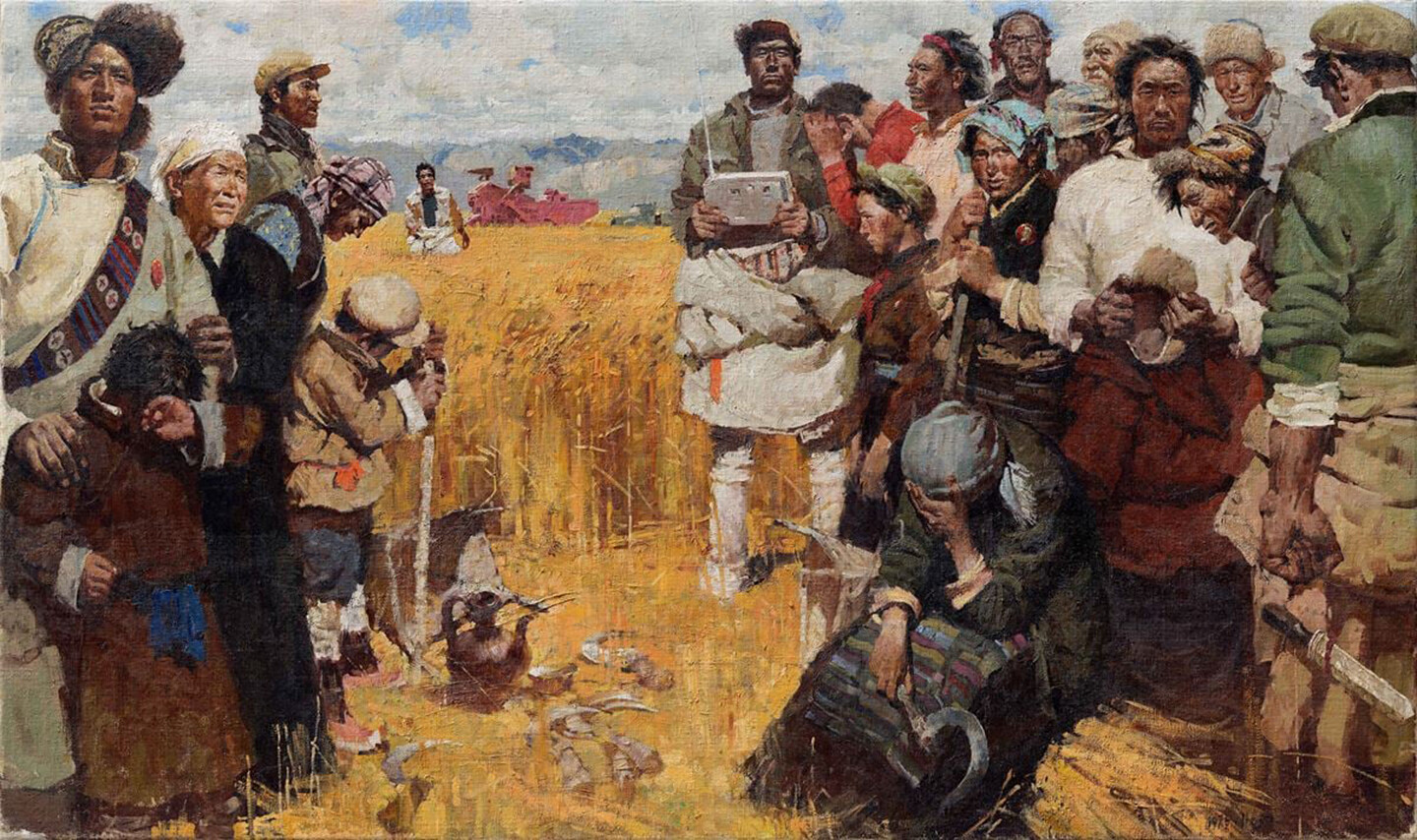

In this issue, Xin Wang details the haunting of China’s contemporary art by socialist-realist pedagogy from the Soviet Union. Perhaps even more significant than this line of influence is its near-total occlusion in Western accounts of China’s avant-garde lineages, no doubt related to Clement Greenberg’s assaults on Soviet socialist realism for epitomizing kitsch. Following Greenberg’s lead, Western scholars may have attempted to be generous by elevating works above lowly pictorial origins, but in doing so, they cleaved them not only from their key influences, but also from a range of formal innovations and attitudes specific to socialist modernity—a version of modernism that continues to persist through its negation, haunting artworks up to today …

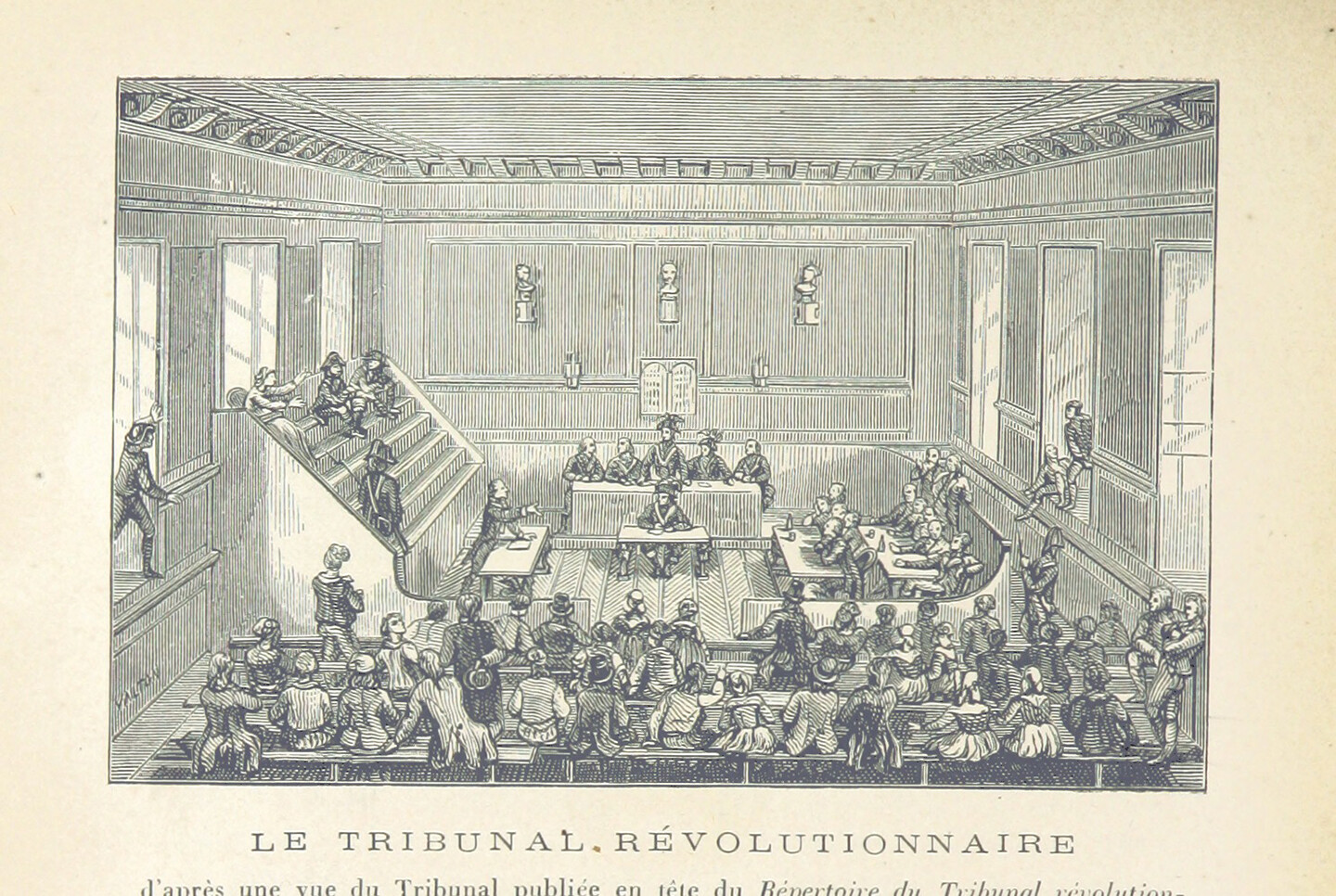

Can and should such movements take over the form of the court, especially given that the judicial system in particular is part of a state apparatus that is based on the constant reproduction of violence? This question is of course to be asked in the context of the much larger question of which stance to take with respect to bourgeois institutions in general: Is there something to be rescued, despite their formalistic, bureaucratic, claustrophobic, cruel, cold, and merciless modes of operation?

We knew there were people with us / dreaming inside the stones / who left our mouths as horses stroked with the light

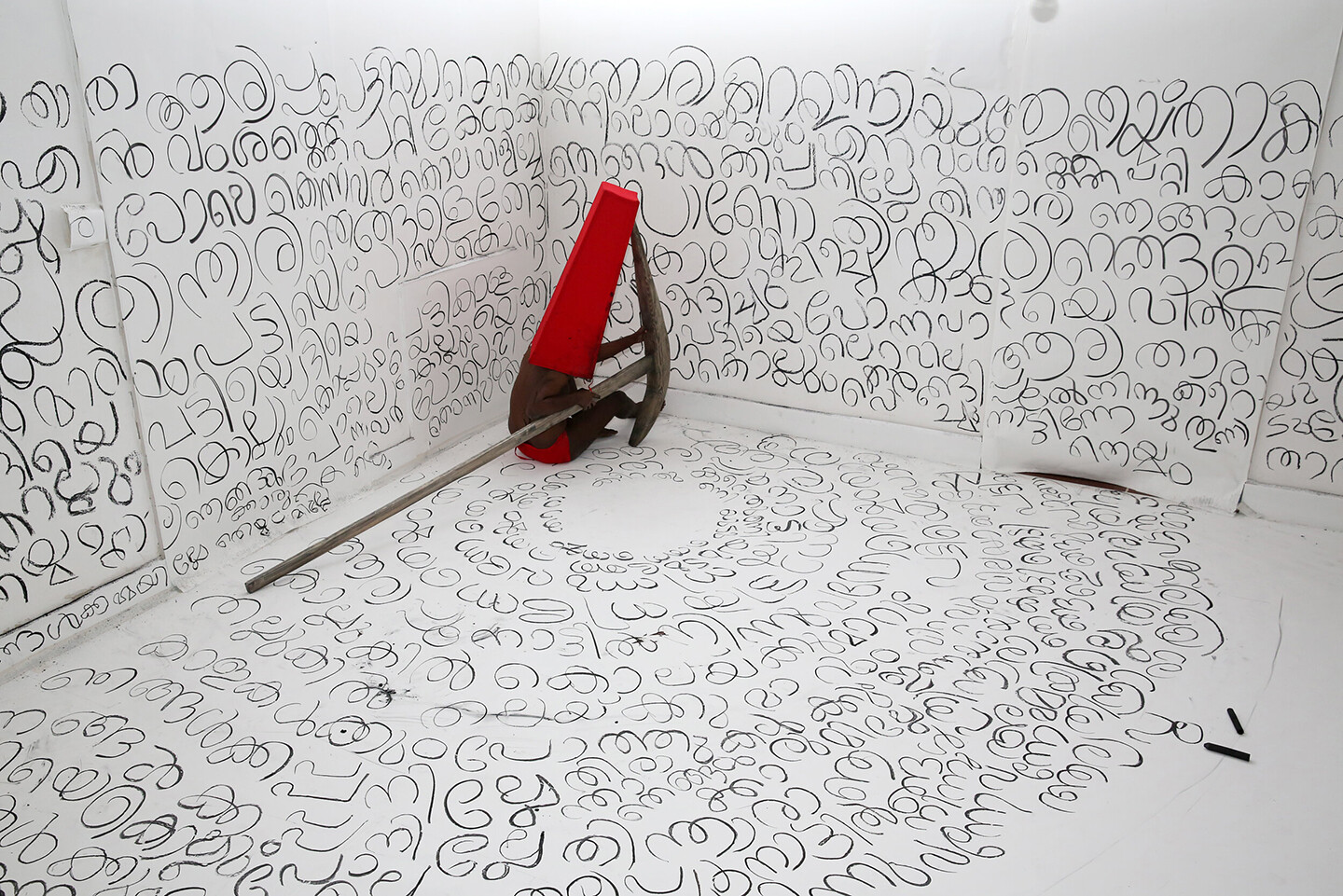

Caste slavery was legitimized through myths, and “justified” through spiritual means. Over the long span of thousands of years, such myths have been compromised and appropriated through many more stories. This is what we Dalits mean when we refer to the oppressive environment long upheld through Brahmanic knowledge production.

By depicting Yamagami’s motive behind the crime and by having discussions about it, we demonstrated that the nature of the problem in Japan is a political crisis. Violence is neither totally negative nor totally positive, but rather something that should be considered on a case-by-case basis. In the end, I chose to depict the contradictions in their entirety, and let the audience come to their own conclusions.

The protagonist of Orbit is a two-hundred-ton boulder that once sat at the heights of the Nevado del Ruiz. On the night of the eruption, it traveled over forty-five kilometers, and was deposited in the center of Armero shortly before midnight. Today, it is a landmark in a ghostly town that, like Herculaneum, stands in ruins. However, unlike its Italian counterpart, Amero receives no conservationist funding or legislative protection. In the absence of state investment, the rock has become an unofficial monument to the dead.

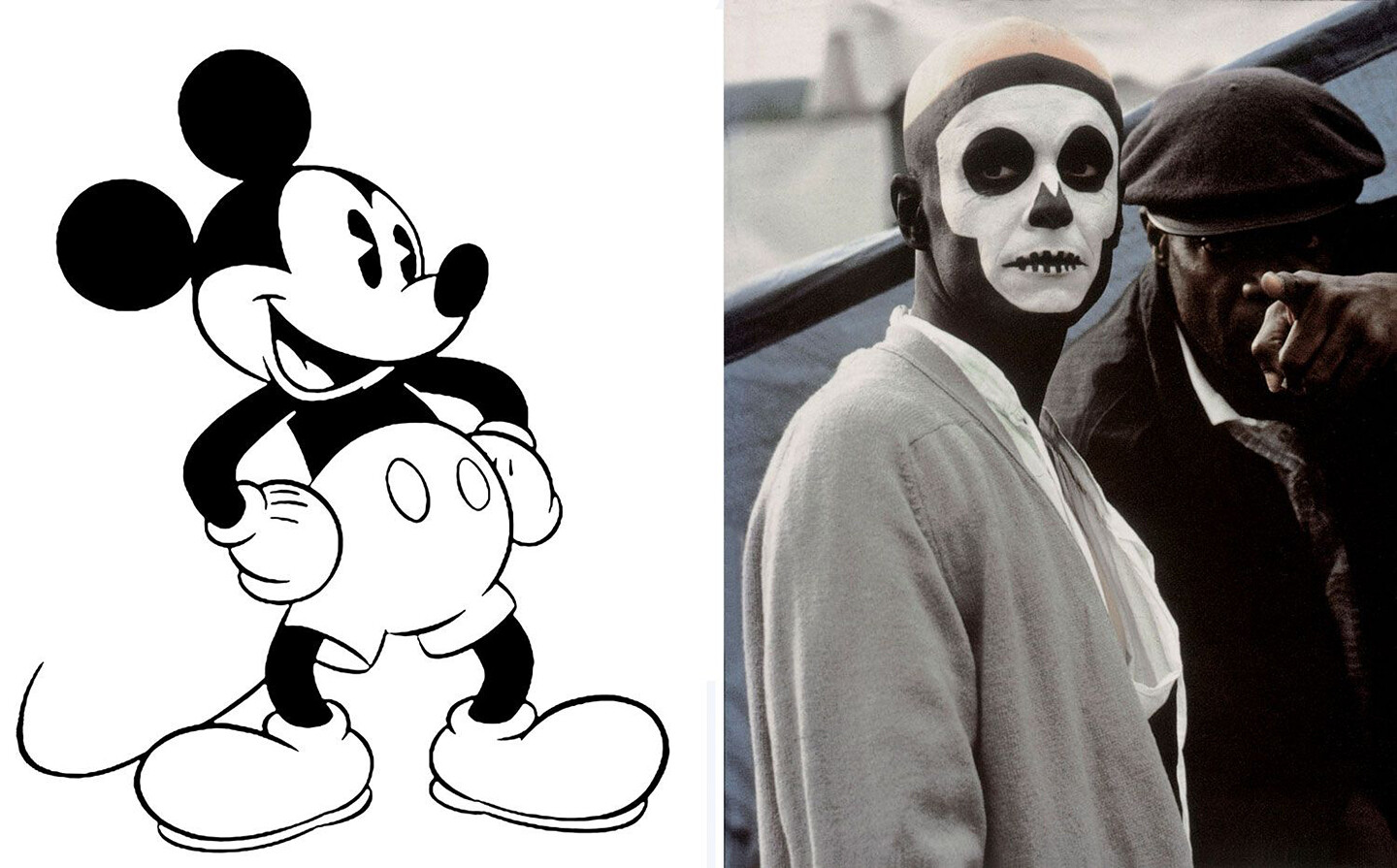

Intensity cannot be destroyed. What exceeds the shape things take cannot properly be located. blackness cannot be captured because blackness is not. It moves. Parastratum, it multiplies all ecologies it comes into contact with.

some things, once said, can never be taken back, and by heeding / these emanations the undead navigate an expanse of featureless terrain / to slake themselves on pity at its spring // even belaboring this list the insipid approach of endings

It is only possible to speak of independence, beyond a political or economic gesture, when it is revealed that the only common experience is the denial of experience—the end of experience, where one can no longer navigate, where separation and mystery are retained, and a sovereignty of each self is assured even if only as an instant, a space, or a way of life.