Transience and Politics

In his 1915 essay “On Transience,” Freud describes a “summer walk through a smiling countryside” in which he and two companions—a “taciturn friend” and a “young but already famous poet”—discuss the beauty of nature. While the young poet admires the pastoral scene that he encounters, he cannot take any “joy in it.” For, as Freud explains:

He was disturbed by the thought that all this beauty was fated to extinction, that it would vanish when winter came like all human beauty and all the beauty and splendour that men have created. All that he would otherwise have loved and admired seemed to him to be shorn of its worth by the transience that was its doom.1

Freud disputes the view of the pessimistic poet. The transience of things, he argues, increases the pleasure that we take in them; the fact that life and beauty, including the beauty of nature, are subject to time, decay, and (eventual) death is precisely the source of their “worth.”

While all of these considerations appear utterly “incontestable” to the psychoanalyst, he notices that they make “no impression” on either of his companions, and he is thus moved to make the following diagnosis: “What spoilt their enjoyment of beauty must have been a revolt in their minds against mourning. Since the mind instinctively recoils from anything that is painful, they felt their enjoyment of beauty interfered with by thoughts of its transience.”2

The despondency felt by the poet and the friend in the face of natural beauty is, for Freud, a kind of immature response. The young companions refuse to mourn; and this refusal constitutes a rebellion against transience and loss, both of which are constitutive of human reality.

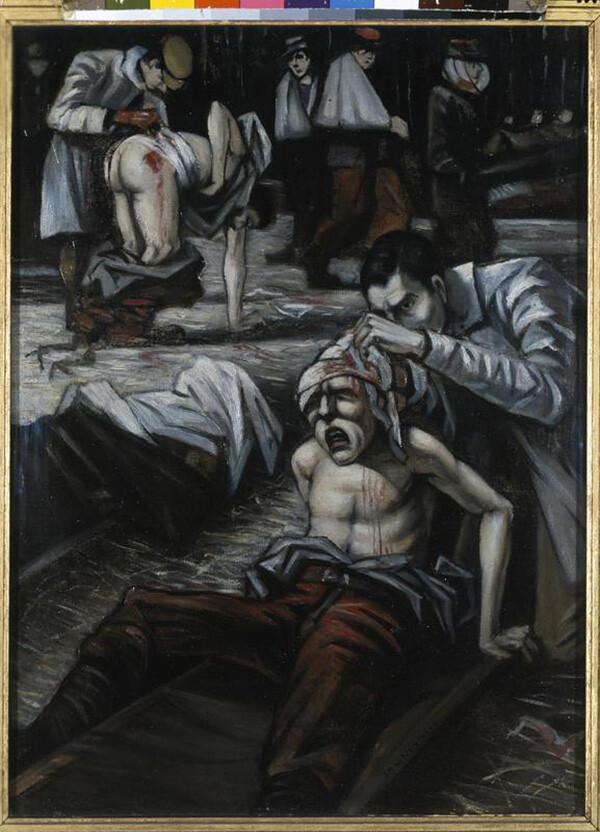

Christopher R. W. Nevinson, The Doctor, 1916. License: Public Domain.

Originally composed as a tribute to Goethe, “On Transience” was written fifteen months into World War I. According to one commentator, Freud strives in the text to “work through” the loss of his own illusions about self and world, performing an act of “psychic repair.” But what illusions, exactly, has the war deprived Freud of? And where does this process of repair ultimately arrive at? The close of the essay is revealing:

The war broke out and robbed the world of its beauties. It destroyed not only the beauty of the countryside through which it passed … and the works of art which it met with on its path … but it also shattered our pride in the achievements of our civilisation … It robbed us of much that we had loved … and showed us how ephemeral were many things that we had regarded as changeless …

Mourning, however painful, comes to a spontaneous end. When it has renounced everything that has been lost, then it has consumed itself, and our libido is once more free … to replace the lost objects by fresh ones, equally or still more precious. It is to be hoped that the same will be true of the losses caused by this war. When once the mourning is over, it will be found that our high opinion of the riches of civilisation has lost nothing from our discovery of their fragility. We shall build up again all that war has destroyed, and perhaps on firmer and more lasting ground.3

Of key theoretical importance here are the essay’s final two points. First, that mourning arrives at a spontaneous and definite end, at which point libido is “free” to be reinvested into new objects. And second, that once the period of war mourning is over, the status quo will (hopefully) be restored, this time on firmer and more lasting ground. There is nothing here, then, to suggest that mourning might involve a critical remembering of what has been; that it might require an ethical reevaluation of the self; or that there might be certain losses (those incurred during a period of catastrophic world devastation, for example) that can only be “worked through” publicly, by means of a collective reenvisioning of society as a whole. In short, there is nothing resembling a dialectics of mourning in “On Transience.”

To take Freud purely on his own terms, however, there would appear to be a glaring conflict between the main philosophical claims of his essay—that transience and loss are essential constituents of human reality; that the fleeting nature of things is internal to their value for us; that the ability to mourn successfully is a precondition for achieving any kind of psychic fulfilment—and what the essay’s conclusion actually performs: a rhetorical move against loss; a rush towards restoration; a resolute defense of the permanence of bourgeois “civilisation” and its “values,” albeit a permanence that now has to be achieved through repetition. At this point, it is difficult not be reminded of Adorno’s barbed comment that appears in the first part of Minima Moralia, written towards the end of the Second World War: “The idea that after this war life will continue ‘normally’ or even that culture might be ‘rebuilt’—as if the rebuilding of culture were not already its negation—this is simply idiotic.”4

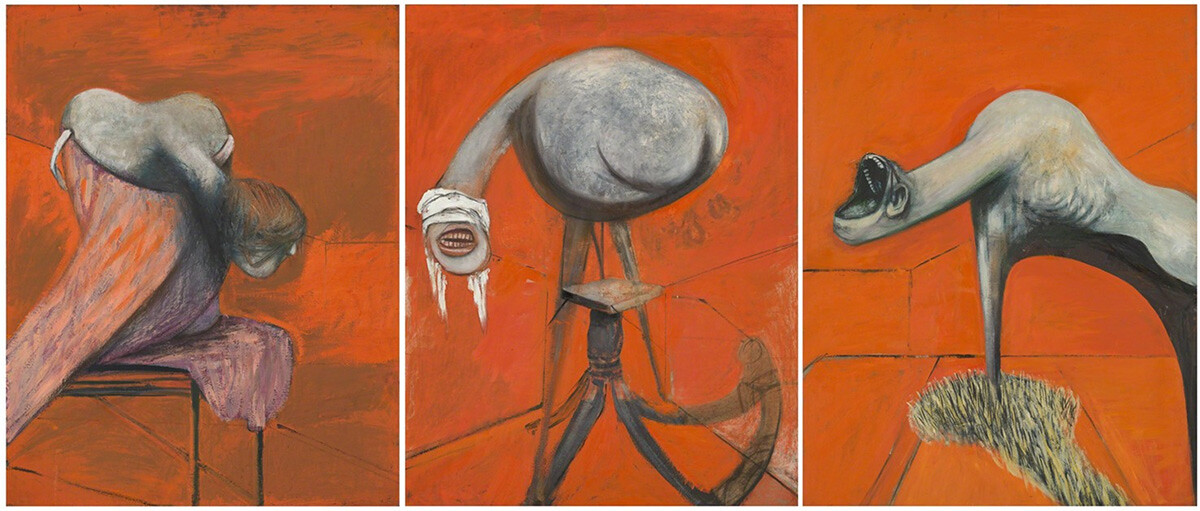

Francis Bacon, Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion, 1944. License: Public Domain.

At the end of “On Transience,” Freud would thus appear to demonstrate a painful “clinging to the object,” a characteristic feature of his own description of melancholia. But here we might also make a more dialectical observation. According to Giorgio Agamben, the loss that is mourned in melancholia is itself a fantasy, designed to make an unobtainable or nonexistent object appear as if lost: “If the libido behaves as if a loss has occurred although nothing has in fact been lost, this is because the libido stages a simulation where what cannot be lost because it has never been possessed appears as lost, and what could never be possessed because it never perhaps existed may be appropriated insofar as it is lost.”5 What we therefore encounter in the conclusion of Freud’s essay is, we might say, a spectacle of mourning for a fictional object—a “noble” bourgeois “civilisation”—which exists only insofar as it can treated as if it were lost. The political reality of what Freud mourns is, however, quite different, as Rosa Luxemburg makes luminously clear in her “Junius Pamphlet,” written in the same year as “On Transience”:

Shamed, dishonoured, wading in blood and dripping with filth—thus stands bourgeois society. And so it is. Not as we usually see it, pretty and chaste, playing the roles of peace and righteousness, of order, of philosophy, ethics and culture. It shows itself in its true, naked form—as a roaring beast, as an orgy of anarchy, as a pestilential breath, devastating culture and humanity.6

Death Drive, Extinction, Entropy

As if Freud can’t prevent himself from returning to the scene of extinction, the topic makes a grand metaphysical reentrance with his “speculative” theory of the death drive in his 1920 essay “Beyond the Pleasure Principle.”7

For the sake of clarity, we might begin here by recapping the key points of Freud’s thesis:

(i) The course of mental events is regulated by the pleasure principle, which aims towards maximizing pleasure—where pleasure is defined as a diminution of excitation.

(ii) The pleasure principle and its aim of keeping the quantity of mental excitation as low and as constant as possible appears, however, to be contradicted by the tendency of individuals to compulsively repeat certain unpleasurable (or traumatic) experiences.

(iii) How, then, to account for this repetition compulsion, which, as Freud says, when it acts “in opposition to the pleasure principle,” often has “the appearance of some demonic force at work”?

(iv) First, repetition stands in place of remembering; and what is repeated is the moment of excitation related to the original trauma. Through repetition the subject aims to “bind” the unbound surplus excitation that produced the psychic wound, transforming it from a freely flowing state into a quiescent one.

(v) Importantly, however, the trauma that drives repetition is not—or not simply—something that has been consciously lived through. Rather, it is something that lies beyond the limits of possible experience: the trace of a primordial loss, which, in Freud’s speculative theory, is the interruption of an original inorganic state.

(vi) A drive, then, “is an urge inherent in organic life to restore an earlier [i.e. inanimate] state of things”; it is “a kind of organic elasticity” that pulls the subject back towards the inorganic state that it once knew. In its clearest form, this hypothesis is stated as follows: “The aim of all life is death” because “inanimate things existed before living ones.”

(vii) Paradoxically, then, in the final analysis the pleasure principle and the death drive turn out to operate according to the same logic: while the former serves the purpose of “reducing tensions,” aiming at a zero-level of mental excitation, the latter marks the tendency of all life to return to the zero-point of the inanimate, a state of final repose.

Antoine Wiertz, The Premature Burial, 1854. License: Public Domain.

To the extent that the death drive in Freud’s theory tends towards the absolute zero-level of inorganicity, it might be read as a metabiological extension of the second law of thermodynamics, the so-called entropy principle.

The physicist Rudolph Clausius first coined the term “entropy” in 1865. Clausius formulates the two laws of thermodynamics as follows: “The energy of the universe is constant”; and “the entropy of the universe tends to a maximum.” What entropy measures is the level of disorder or randomness within a given system—that is, how much energy is “disorganized” or beyond “use.” According to the second law, within any isolated system energy moves inexorably in the direction of increasing entropy.

Commenting on the second law, the character Sally (Judy Davis) in Woody Allen’s film Husbands and Wives says: “It’s the second law of thermodynamics: Sooner or later everything turns to shit.” This witticism turns out to be surprisingly accurate. When an isolated system reaches a point of maximum entropy, this is a state of thermodynamic equilibrium. In equilibrium we arrive at the so-called heat death of the universe: a state of affairs in which all usable energy has been expended and the system dies. This state of cosmological exhaustion is brilliantly captured by the poet Byron in the opening lines of his 1816 work “Darkness,” as if the poet had already discovered the second law half a century before its official scientific formulation:

I had a dream, which was not all a dream.

The bright sun was extinguish’d, and the stars

Did wander darkling in the eternal space,

Rayless, and pathless, and the icy earth

Swung blind and blackening in the moonless air …

The world was void.8

The entropy thesis might thus be thought of as the law of a universal death drive, as foretelling both earthly and cosmic extinction. The second law’s message of ultimate fatality no doubt goes some way towards explaining its enduring appeal for a certain strand of postwar pessimistic thought. In an extraordinary passage that appears towards the end of his 1955 memoir Tristes Tropiques, the structural anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss transforms the entropy thesis into a discourse about the inevitable disintegration of human civilization:

The world began without man and will end without him. But far from being opposed to universal decline, [man] himself appears as perhaps the most effective agent working towards the disintegration of the original order of things and hurrying on powerfully organized matter towards ever greater inertia, an inertia which one day will be final … Thus it is that civilization, taken as a whole, can be described as an extraordinarily complex mechanism, which we might be tempted to see as offering an opportunity of survival for the human world, if its function were not to produce what physicists call entropy, that is inertia.9

While Lévi-Strauss’s pessimistic entropology sees culture itself as necessarily death driven, Norbert Weiner, in his study Cybernetics: Or Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine, formulates a cognitivist version of the same hypothesis, applying the entropy law (somewhat bizarrely) to the human brain:

We may be facing one of those limitations of nature in which highly specialised organs reach a level of declining efficiency and ultimately lead to the extinction of the species. The human brain may be as far along on its road to this destructive specialisation as the great nose horns of the last of the titanotheres.10

At this point, some political and historical framing is in order. Science, like philosophy, is its own time apprehended in thought. According to George Caffentzis, “Physics is not only about Nature and applied just to technology: its essential function is to provide models of capitalist work.” More than just a scientific law, then, the entropy principle betrays Victorian capitalism’s anxieties about its own extinction. For Caffentzis, “the second law announces the apocalypse characteristic of productivity-craving capital: heat death. Each cycle of work increases the unavailability of energy for work.”11

It is no surprise, therefore, that thermodynamics (the study of energy, primarily in regard to heat and work) becomes the science after the revolutions of 1848. It is also no surprise that the first formulation of the second law emerges directly out of the study of “inefficient” capitalist machines. Observing the waste of mechanical energy in steam engines, William Thomson (Lord Kelvin) concludes that (i) there is in the material world a universal tendency towards the dissipation of energy; that (ii) any restoration of mechanical energy is impossible; and that (iii) within a finite period of time the earth will be “unfit for human habitation,” thereby returning to an earlier state of thermal equilibrium.12 This leap from engine technology to cosmology, from non-perfect machines to a non-mystical apocalypse, introduces into early modernist science a double notion of time: time conceived as the eternally repetitive process of capitalist production and accumulation; and time conceived under the mythic sign of predestination—all life as mere being-towards-universal-death.

Dialectics of the Death Drive

The question facing us now is how to read Freud’s notion of the death dialectically against this background. While the second law expresses the irreversible tendency of all closed systems towards exhaustion and death, Freud speaks of the universal endeavor of all living things to return to the quiescence of the inanimate; and in this respect, as Michel Serres points out, Freud clearly “aligns himself” with the “findings” of thermodynamics.13 But here it might be better to say, picking up a line of thought in Althusser, that Freud has to think of his discovery in “imported concepts”—in this case, concepts borrowed from the physics of his time, which cannot help but bear the trace of “the ideological world in which they swim.”14

To think of the death drive in relation to the entropy principle is, however, to run up against an immediate problem: a blind spot in Freud’s own thinking. This is, quite simply, that the death drive cannot help but work against itself, resisting its own goal. If, on the one hand, the death drive aims at achieving a state of equilibrium or quiescence, then, on the other hand, the drives themselves are generators of internal tensions that permanently prevent the psyche from achieving a state of absolute rest. In this respect, the death drive turns out to be a kind of “self-defeating mechanism,” and as such an anti-entropic force.15

We can see this very clearly if we return to the so-called compulsion to repeat. According to Freud, the subject is driven to relive particular traumas in order that the psyche might “master” the experience of overwhelming pain, “bind” the surplus of excitation, and reinstate the “authority” of the pleasure principle. It is through repetition, on Freud’s account, that the subject is able to bring about a reduction of psychic tensions. But the problem with this strategy is that it simply doesn’t work. In fact it exacerbates the very disquietude which it aims to remedy. As Adrian Johnston neatly observes:

Reliving the nightmares of traumas again and again doesn’t end up gradually dissipating … the horrible, terrifying maelstrom of negative effects they arouse. Instead, the … labours of repetition … have the effect of repeatedly re-traumatising the psyche … Obviously, this strategy for coping with trauma is a failing one. And yet, the psyche gets stuck stubbornly pursuing it nonetheless.16

The subject’s compulsion to repeat is thus always a failed attempt at recovery; and it is a failed attempt because the trauma being repeated is itself a repetition of another trauma. This other trauma is not the infantile trauma of birth or helplessness, but rather the fundamental negativity (the void or gap) at the core of subjectivity itself.

We can thus arrive at a first conclusion. To speak of the death drive is not to evoke some mysterious force aimed at death and destruction; it is not, as it so often figures in the popular imagination, a thrust towards war, aggression, and ecocide. Rather, the death drive is connected to the compulsion to repeat, to a condition of stuckness. But it is repetition—stuckness—of a specific kind: it signals those breaks and interruptions in the “normal” psychic economy where the pleasure principle fails to assert its dominance; it denotes those points of excess that mark the subject’s (all-too-human) failure to arrive at a state of inertial equilibrium. In this respect, the death drive can be seen as split: on the one hand, its goal is the absolute zero of libidinal-affective quiescence; on the other hand, its aim is endless repetition, which, far from eliminating excitation, actively produces it. The drive thus repeats the failure to reach its own goal; and yet in so doing it also repeats the enjoyment which this negative-repetitive process necessarily generates.

Concisely put, then, what is death-like about the death drive is, paradoxically, its undeadness: its blind persistence, its inability to ever let up. The drive repeats endlessly, as a kind of acephalous force; and it does so in order to enjoy. As Lacan comments in Seminar XVII, “What necessitates repetition is jouissance”—jouissance is what drives repetition.17 But here we need to be specific. First, what gets repeated, and what enjoyment sticks to, are signifiers.18 Repetition is thus fundamentally the repetition—the insistence—of speech.

We get a clear example of the enjoyment of repetition in Samuel Beckett’s play Endgame, in the looped repartee that takes place between the blind Master Hamm and his long-suffering domestic servant, Clov. At one point in the action, Clov states, “All life long the same questions, the same answers,” to which Hamm responds, “I love the old questions … Ah the old questions, the old answers, there’s nothing like them!” When Clov later asks, “What is there to keep me here?” Hamm’s reply is simple and direct: “The dialogue.” What Endgame thus dramatizes is (among other things) the impossibility of escaping ourselves as subjects who incessantly enjoy the form of life that is speaking—a form of life, we might add, that appears to grow more enjoyable the more absurd and repetitious it becomes. As Stanley Cavell writes (four decades before the arrival of Twitter): “We have to talk, whether we have something to say or not; and the less we want to say and hear the more wilfully we talk and are subjected to talk.”19

The second point to make about repetition is that it is never simply a reproduction of the same; instead, it engenders difference. Repetition, as Lacan remarks, “is turned towards the ludic, which finds its dimension in [the] new,” opening onto “the most radical diversity.”20 This connection between repetition, creativity, and difference leads us back to Freud; and not simply to his famous example of the fort/da game, but also to his point that what the subject wants is to die in its own fashion, to navigate its own unique path to death. This desire, we should be clear, is not an impulse to self-annihilation, but rather a desire for singularity: a wish to die differently, which is to say, a wish to keep repeating and enjoying one’s own symptom, in one’s own way, right up until the very end. Taken in this sense, the death drive entails a crucial ethical dimension: it is what allows the subject to free itself from the entropy that it otherwise cannot help producing; it is the very excess of life which makes it possible for the subject to proclaim: “I did it my way.”21

***

In what ways does the death drive become visible today, in an era of converging catastrophes? How does it express itself when the biological foundation on which capital rests has been pushed towards the brink, and when the social bond appears to have been utterly severed?

We might turn here to two examples, two specific modalities of the contemporary death drive. First, anti-natalism: the view that the human species is morally obligated to bring about its own extinction by refusing to procreate. The ecological variant of this position argues that voluntary human extinction is necessary in order for nature to flourish once again. And second, de-extinction: not, in this case, the resurrection of extinct species, but rather the revival of certain organs of social, historical, and political imagination.

Anti-natalism: Undialectical Pessimism

In Margaret Atwood’s 1981 novel Bodily Harm, the protagonist, Rennie, recalls a piece of graffiti she had once seen written on a toilet wall: “Life is just another sexually transmitted social disease.”22 This sentiment perfectly encapsulates the worldview of the philosopher-detective Rustin (“Rust”) Cohle, whose character appears in season one of the HBO drama True Detective (2014). In episode one, Cohle (Matthew McConaughey) and his partner Martin (“Marty”) Hart (Woody Harrelson) are driving through a desolate Louisiana landscape, trying to solve a horrific murder case, when Cohle is asked by Hart to explain his philosophical beliefs. Cohle’s response, almost comic in its tragic seriousness, evokes the ghosts of Schopenhauer and Emil Cioran:

I think human consciousness is a tragic misstep in human evolution. We became too self-aware; nature created an aspect of nature separate from itself. We are creatures that should not exist by natural law … I think the honorable thing for our species to do is deny our programming, stop reproducing, walk hand in hand into extinction, one last midnight, brothers and sisters, opting out of a raw deal.23

Cohle is here absolutely anti-natal: humanity should cease procreating and bring about its own extinction. But it is not only that human beings should “opt out” of the raw deal—we might say, the ordeal—that is life, but rather that it would be better for them not to have come into existence in the first place. The world, as Cohle says, is just “a giant gutter in outer space … Think of the hubris it must take to yank a soul out of nonexistence into this … meat, to force a life into this … thresher.” If one does have the misfortune of being born, then the best that can happen is a swift and early death: “The trouble with dying later is you’ve already grown up. The damage is done. It’s too late.”

This line of thinking has a rich intellectual history. In Oedipus at Colonus, lamenting the hero’s tragic fate, Sophocles has the chorus pronounce the famous and frightening lines:

Not to be born is best

by far: the next-best course,

once born, is double-quick

return to source.24

This tragic Sophoclean maxim also plays a key role for Nietzsche. In The Birth of Tragedy, Nietzsche recounts the story of King Midas, who confronts the wise Silenus, companion of Dionysus, and asks him: What is the best and most desirable thing for humankind? Silenus responds with a “shrill laugh” before uttering the following words:

Wretched ephemeral race, children of chance and tribulation, why do you force me to tell you the very thing which it would be most profitable for you not to hear? The very best thing is utterly beyond your reach: not to have been born, not to be, to be nothing. However, the second-best thing for you is to die soon.25

The pronouncement of the Sophoclean chorus finds its way into Freud’s Jokes and Their Relation to the Unconscious (1905), where it is given a particular comic twist: “Never to be born is the best thing for mortal men. ‘But,’ adds the philosophical comment [in Fliegende Blätter,] ‘this happens to scarcely one person in a hundred thousand.’”26 Freud’s proto-Beckettian witticism lands nicely; the somber words of Sophocles are well met by the satirical reply.27 But Freud himself goes on to spoil the joke. Sounding like an uptight analytical philosopher, he says that the initial proposition, the pronouncement of the chorus, is ultimately “nonsense,” and that this nonsense is precisely what is illuminated by the silly punchline. As Freud explains,

the addition is attached to the original statement as an indisputably correct limitation, and is thus able to open our eyes to the fact that this solemnly accepted piece of wisdom is itself not much better than a piece of nonsense. Anyone who is not born is not a mortal man at all, and there is no good and no best for him.28

Freud appears to completely miss the point: of course the never-existent are not in a position to proclaim that “the best” has happened to them, but this isn’t what Sophocles’s chorus is getting at. Rather, what its verse conveys is that coming into existence is always bad for those who suffer this fate. Consequently, although we might not be able to say of the never-existent that never existing is best for them, we can say—rightly or wrongly—of the existent that existence is bad for them and thus that it would have been better never to have been born. Understood in this way, life itself comes to be seen as a kind of tragic accident, a great ontological mistake. As Aaron Schuster neatly formulates it: “The human being is the sick animal that does not live its life but lives its failure not to be born.”29

***

As we saw in the case of Rust Cohle, the anti-natalist position attempts to provide one answer to the question of what is to be done when life is understood as a disease, as nothing but a futile squandering of organic material. No human life, according to this position, is ever worth the harm; even the most fortunate would be better off had they never existed. In any life, the quanta of pain always exceeds the quanta of pleasure, and therefore the only solution, according to the negative utilitarian logic that anti-natalism applies, is to refrain from bringing any new life into the world.30 The goal here, then, is a controlled extinction of the human species: by desisting from procreation we would eradicate suffering and eventually arrive at Schopenhauer’s vision of a “crystalline state” or lifeless world.31 In the words of the philosopher Peter Wessel Zapffe: “Know yourself—be infertile, and let the earth be silent after you.”32

Might it be possible to understand this position as a kind of enlightened pessimism? Could we not say, as Horkheimer says of Schopenhauer, that anti-natalism speaks “the truth,” that in renouncing optimism it sees existence as it really is? Our answer here should be a resolute no—although our objection will no doubt sound somewhat counterintuitive: The problem with anti-natalism is not that its pessimism is too radical, but rather that its pessimism isn’t radical enough.

The equation of existence with universal suffering is a false totalization. While anti-natalism harps on the pains of existence—nausea, boredom, melancholia, loneliness, chronic disease, bereavement—it has nothing to say about how human misery is unequally distributed along lines of class, race, and gender; or how it might be exacerbated by such trifling matters as the relentless exploitation of labor or the continued expansion of a permanent war economy. While anti-natalism is thus relentlessly pessimistic about “life,” it is eerily silent about the profit system that is responsible for specific kinds of life-making. Its ideological starting point is to present reified human relations as the natural condition: life just is a business that does not cover its costs.

But the problems with anti-natalism go further still. In addition to its apolitical pathology, it is also blind to the dialectics of human desire. According to the anti-natalist, the human subject is incapable of attaining any real and lasting pleasure or happiness, and this makes life an ultimately worthless enterprise. But the thing about pleasure and happiness is that they are rarely what they seem. In Beckett’s Endgame, for example, Hamm (a kind of anti-natalist figure himself) opens with the line: “Me to play … Can there be misery loftier than mine?” This is a wonderfully ambiguous formulation: on the one hand, Hamm is asking whether it’s possible for anyone to suffer as much as him; on the other hand, he is announcing the absolute superiority of his own suffering—a superiority which he clearly enjoys.

Proving that the human subject always has an eccentric relationship with its own jouissance, Hamm spends most of the play engaged in a discourse of despair (“I’ll tell you the combination of the larder if you promise to finish me off”), only to find that his unhappiness is precisely the source of his enjoyment. Unhappiness, we might say, always has a hole in it; and it is through this hole that happiness and enjoyment emerge as a kind of libidinal leakage or affective ooze.

This is precisely what anti-natalism cannot grasp, or perhaps does not want to know. It does not see that pessimism is the fixed point around which its own enjoyment circulates. This brings us back to the death drive, to the excess of life, what is in life more than life itself. What singularizes the anti-natalist, what provides them with a specific way of going on, just is the view that the best is not to be born and that our ethical purpose now is to bring about the extinction of the species by refusing to procreate. This is a life that sets itself against life, that carries death at its very core; but it is a life, nevertheless. If, strictly speaking, the anti-natalist should seek to return to source as quickly as possible, then why, we might ask, do they carry on living? Is it not because the surplus satisfaction found in their own bleak worldview is itself a precious treasure that they wish to protect at all costs?

Ecological Anti-natalism: A False Exit from Catastrophe

If pessimistic abolitionism—the variety of anti-natalism we have just been discussing—sees existence as bad primarily for the person who exists, then ecological anti-natalism views human existence as bad for nature. At the beginning of Nina Paley’s 2002 short film Thank You For Not Breeding, Les U. Knight, founder of the Voluntary Human Extinction Movement (VHEMT), argues that the recovery of the earth’s biosphere depends upon the human species being allowed to die out. In the same film, Reverend Chris Korda, leader of the Church of Euthanasia, says that “we are treating the earth like a cigar, we are smoking it … and at some point there is going to be nothing left but ash.” The Church has one commandment, “Thou Shall not Procreate,” and it promotes four “pillars”: suicide, abortion, sodomy (defined as any nonreproductive sexual act), and cannibalism (for those who insist on eating meat). The main slogan employed by the Church is: Save the Planet, Kill Yourself.33

This kind of death activism finds its most systematic articulation in Patricia MacCormack’s The Ahuman Manifesto (2020). According to MacCormack, “the death of the human is a necessity for all life to flourish.” As the world groans “under the weight of the parasitic pestilence of human life,” human extinction presents itself not only as a logical solution, but also as an ethical one:

The death of the human species is the most life-affirming event that could liberate the natural world from oppression … Our death would be an act of affirmative ethics which would far exceed any localised acts of compassion because those acts would be bound by human contracts, social laws and the prevalent status of beings.

Bringing about the end of the “anthropocentric world” through self-extinction, refusing notions of futurity grounded on the idea of the “special child,” is, for MacCormack, “a form of secular ecstasy”: it “opens up the void that is a voluminous everything and wants for nothing.”34

A mummy from Guanajuato. License: Public Domain.

There is an interesting unity-in-difference that connects this dark Spinozian ecological anti-natalism with Lee Edelman’s polemical No Future thesis published in 2004. For Edelman, contemporary social relations are organized by the imperatives of “reproductive futurism,” in which the image of the child serves as the “horizon of every acknowledged politics, the fantasmatic beneficiary of every political intervention.” The child, he argues, “has come to embody for us the telos of the social order and come to be seen as the one for whom that order is held in perpetual trust.” What would it mean, then, to refuse the child “as the emblem of futurity’s unquestioned value”? How might one say no to “the fascism of the baby’s face”?35 Edelman suggests an anti-natal, antisocial, future-negating queerness: one involving an unconditional fidelity to jouissance and the death drive.36

Edelman’s ostensibly radical theory is, however, problematic in at least two respects. First, playing fast and loose with Lacan’s ideas, Edelman conceives of the death drive as pure negativity: a negativity which opposes “every form of social viability” and undoes all ideas of the future. If such a reading is crudely undialectical—blind to the death drive’s generative potential—then this theoretical misstep also has political consequences. For if the death drive, embodied in Edelman’s figure of the “sinthomosexual,” really does take delight in exclaiming “fuck off” in the face of the future,37 then this begins to sound like rather strange polemics at a moment when the human species has, in Thom van Dooren’s phrase, arrived at “the edge of extinction.” This situation already produces a new temporal landscape beyond the fantasy of reproductive futurism, one characterized by what van Dooren calls “a slow unravelling of intimately entangled ways of life that begins long before the death of the last individual and continues to ripple forward long afterward, drawing in living beings in a range of different ways.”38 No future indeed.

Edelman’s articulation of queer negativity bears a curious resemblance to Marx’s famous description of capitalism in the 1848 Manifesto: “uninterrupted disturbance of all social conditions, everlasting uncertainty … All fixed, fast-frozen relations, with their train of ancient and venerable prejudices and opinions, are swept away … All that is solid melts into air, all that is holy is profaned.”39 This leads us directly to the second problem with Edelman’s polemic. For him, liberation from futurism consists in voiding “every notion of the general good,” refusing “any backdoor hope for dialectical access to meaning,” and relinquishing the cruel optimism that attaches to all political projects.40 It is precisely here, then, that a further connection to ecological anti-natalism becomes clear. Neither position can think how things might be beyond the future as mere replication of the present; both positions, in their different ways, have absorbed (and been absorbed by) the infamous neoliberal slogan: “There is no alternative.” Symptoms of the revival of the “end of history” narrative, and lacking any political proposal beyond pitting a minoritarian vanguard against the mass of normie “breeders,” both philosophies thus offer only a nihilistic negativity: a negativity that ultimately mirrors the auto-destructiveness of capitalism itself.

***

It might be said that only those who have a future in the first place have the luxury of flirting with the idea of rejecting it. Those reduced to nothing by the profit system are highly unlikely to desire the liquidation of the future or indeed the wholesale extinction of the human species—although they might well be up for killing their boss and stealing his car. While queer negativity and ecological anti-natalism might remind us of the emptiness of the bourgeois dictum that “life is good, in spite of all,” they nevertheless leave us politically short-changed: locking us in to a dull presentism in which the possibility of alternative collective futures remains eternally repressed.

Returning specifically to ecological anti-natalism, we might ask, in a final cranking of the philosophical gears, what actually grounds the desire for human auto-extinction? What ideas motivate the wish for this particular kind of radical sacrifice? The first thing to say here is that the ecological anti-natalist appears to be suffering from the specific Western pathology that is species shame, linked, in this specific case, to the hypothesized advent of a new geological epoch wherein the effects of “human civilization” are said to have completely altered the planet’s ecosystems. Thus understood, voluntary human extinction is a response to the arrival of the so-called Anthropocene, a kind of necessary self-punishment for what is perceived to be exploitative, eco-phobic humanity, the destructive anthropos.

But here we might give this reading something of a twist, tilting it back in the direction of the death drive. As Adorno comments in one of his late lectures on metaphysics: “The terror of death today is largely the terror of seeing how much the living resemble it.” He continues: “There has been a change in the rock strata of experience … Death no longer accords with the life of any individual … There is no longer an epic or a biblical death … The reconciliation of life, as something rounded and closed in itself, with death, is no longer possible today.”41 Against this background, might we not say ecological anti-natalism is not—or not simply—concerned with liberating nonhuman nature, but rather with pursuing a literal attempt to die differently, to die heroically, to die as if the sickness has been worth living through after all? If, as Adorno puts it, “the individual today no longer exists and death is thus the annihilation of nothing,” might not human auto-extinction be a desire to die again, to die better, as Alenka Zupančič puts it in a wonderful paraphrase of Beckett?42

The paradox here, of course, is that the anti-natalist turns out to be acting just as affirmatively as any other worldly human subject—perhaps even more so. The affirmation of species annihilation is just as “heroic” as any form of tech-utopianism that claims that it, too, can solve all of nature’s problems

There is, finally, something rather comic about all of this. For what all the talk of death and self-extinction overlooks is the fact that we are, in one sense, yet to be fully born: still living in prehistory, as Marx famously puts it. As Adorno comments in his 1962 lecture “Progress”: “We cannot assume that humanity already exists … Progress would be the very establishment of humanity in the first place, whose prospect opens up only in the face of its own extinction.”43

The realization of this prospect involves a particular kind of de-extinction: a revival of the organs of historical and social imagination, and a shift into the zone of politics proper. Such a shift hinges upon the recognition that only the negation of this world—a world of serial and interconnected catastrophes—ends the prospect of the end of the world—understood here not as a sudden death, but rather as an incremental decay, the slow unravelling of intimately entangled forms of life. As Ernst Bloch points out: “The true genesis is not at the beginning, but at the end, and it starts to begin only when society and existence become radical.”44 To terminate the threat of the end (as the biological end of all things) will therefore mean beginning again at the end (of prehistory): abolishing a mode of political and economic life which seeks to tether us all—the yet to be born—to a sick but undying present.

Sigmund Freud, “On Transience,” in Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, vol. 14, ed. and trans. James Strachey (Hogarth Press, 1957), 305. Emphasis in original.

Freud, “On Transience,” 305.

Freud, “On Transience,” 306.

Theodor Adorno, Minima Moralia (Verso, 2005), 55. Translation slightly modified.

Giorgio Agamben, Stanzas: Words and Phantasm in Western Culture, trans. Robert L. Martinez (University of Minnesota Press, 1993), 20. Emphasis in original.

Rosa Luxemburg, “The Junius Pamphlet, Pt. 1: The Crisis in German Social Democracy,” in Selected Political Writings of Rosa Luxemburg, ed. Dick Howard (Monthly Review Press, 1971), 324.

Sigmund Freud, “Beyond the Pleasure Principle,” in Standard Edition, vol. 18 (Hogarth Press, 1955).

Lord Byron, Poetical Works (Oxford University Press, 1945), 95.

Claude Lévi-Strauss, Tristes Tropiques (Penguin, 2011), 413.

Norbert Wiener, Cybernetics, or Control and Communication in the Animal and Machine (MIT Press, 2013), 154.

George Caffentzis, Letters of Fire and Blood: Work, Machines, and the Crisis of Capitalism (PM Press, 2013), 13, 14, 12.

William Thomson, “On a Universal Tendency in Nature to the Dissipation of Mechanical Energy” (1852), cited in Crosbie Smith and M. Norbert Wise, Energy and Empire: A Biographical Study of Lord Kelvin (Cambridge University Press, 1989), 499–500.

Michel Serres, Hermes: Literature, Science, Philosophy (Johns Hopkins University Press, 1982), 72.

Louis Althusser, On Ideology (Verso, 2008), 149. Emphasis in original.

Adrian Johnston, Time Drive: Metapsychology and the Splitting of the Drive (Northwestern University Press, 2005), 183. Emphasis in original.

Adrian Johnston, “The Weakness of Nature: Hegel, Freud, Lacan and Negativity Materialized,” in Hegel and the Infinite: Religion, Politics and Dialectic, ed. Slavoj Žižek, Clayton Crockett, and Creston Davis (Columbia University Press, 2011), 160.

Jacques Lacan, The Seminar of Jacques Lacan: The Other Side of Psychoanalysis (Book XVII), ed. Jacques-Alain Miller, trans. Russell Grigg (Norton, 2007), 45.

For Lacan, the signifier is the basic unit of language. When Lacan speaks of signifiers he is usually referring simply to “words,” although the two terms are not, strictly speaking, equivalent. For a useful definition, see the entry “Signifier (significant)” in Dylan Evans, A Dictionary of Lacanian Psychoanalysis (Routledge, 1996), 186–87.

Stanley Cavell, Must We Mean What We Say? (Cambridge University press, 1976), 161.

Jacques Lacan, The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psycho-Analysis, ed. Jacques-Alain Miller, trans. Alan Sheridan (Routledge, 2018), 61.

See Eric Santner, who here draws deliberately on the lyrics of the song made famous by Frank Sinatra, and, we should add, The Sex Pistols. Santner, Untying Things Together: Philosophy, Literature, and a Life in Theory (University of Chicago Press, 2022), 194.

Margaret Atwood, Bodily Harm (Emblem, 2010), 181.

The ideas put forward in Cohle’s speech also have clear connections with ideas found in Thomas Ligotti, The Conspiracy Against the Human Race (Penguin, 2018).

Sophocles, Four Tragedies, trans. Oliver Taplin (Oxford University Press, 2015), 272.

Friedrich Nietzsche, The Birth of Tragedy and Other Writings, trans. Ronald Spiers (Cambridge University Press, 1999), 23. Emphasis in original.

Sigmund Freud, Standard Edition, vol. 8 (Hogarth Press, 1960), 57.

See Bernard Williams, “The Makropulos Case: Reflections on the Tedium of Immortality,” in Problems of the Self (Cambridge University Press, 1999), 87.

Freud, Standard Edition, vol. 8, 57. Emphasis in original.

Aaron Schuster, The Trouble with Pleasure: Deleuze and Psychoanalysis (MIT Press, 2016), 15.

This is, in essence, the argument of David Benatar’s Better Never to Have Been: The Harm of Coming into Being (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2006). For an overview of anti-natalist arguments, see Ken Coats, Anti-Natalism: Rejectionist Philosophy from Buddhism to Benatar (Design Publishing, 2014).

Arthur Schopenhauer, Studies in Pessimism, trans. T. Bailey Saunders (Swan Sonnenschein & Co., 1891), 14.

Peter Wessel Zapffe, “The Last Messiah,” Philosophy Now, no. 45 (March–April 2004). Translation slightly amended.

“A Brief History of the Church of Euthanasia,” churchofeuthanasia.org →.

Patricia MacCormack, The Ahuman Manifesto: Activism for the Age of the Anthropocene (Bloomsbury, 2020), 140, 162, 141, 10, 9.

Lee Edelman, No Future: Queer Theory and the Death Drive (Duke University Press, 2004), 2, 3, 11, 4, 75.

The figure who embodies this radical negativity is the “sinthomosexual,” a neologism which Edelman adapts from Lacan’s notion of the sinthome, the unanalysable kernel of the subject which binds together the three registers of the real, the imaginary, and the symbolic.

Edelman, No Future, 29. It is perhaps not insignificant to note that Edelman’s hostility is, at times, explicitly directly at working-class female children: “Fuck Annie, fuck the waif in Les Mis” (29).

Thom van Dooren, Flight Ways: Life and Loss at the Edge of Extinction (Columbia University Press, 2014), 12.

Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, The Communist Manifesto (London: Penguin, 2002), 223.

Edelman, No Future, 6.

Theodor W. Adorno, Metaphysics: Concept and Problems, trans. Edmund Jephcott (Polity Press, 2001), 136.

Adorno, Metaphysics, 136; Alenka Zupančič, What is Sex? (MIT Press, 2017), 106.

Theodor Adorno, “Progress,” in Critical Models (Columbia University Press, 2005), 144. Emphasis in original.

Ernst Bloch, On Karl Marx (Verso, 2018), 44.

Category

Subject

Thanks to Maria Balaska, Peter Buse, Rohit Goel, and Frank Ruda for comments on an earlier version of this essay. Additional thanks to Elvia Wilk for editorial input.