Continued from “We Too Were Modern, Part I: Of Brazilian Autophagic Flowers and Navigators”

It is possible to state here that there is no pure settler nor pure colonizer of Brazil or anywhere, just as there is no pure law nor pure exploration. And yet their distance between rhetoric and promise allows for a fusion into a legitimately Brazilian Frankenstein—the rapist Father who does not give the law, but exploits and enslaves through the imminence of his law. It is precisely in the legitimation of this figure that both positivism and Brazil’s republic are inserted—not in a redemptive hope for Comte’s social sentiment, but as part of the national museum of hybridizations between colonized and colonizer. These hybridizations feed on the maxim “I explore to give the law,” or simply “I give the law because I explore”—leading to a law and a government made of nothing but an infinite series of potlatches.

Marcel Mauss described a potlatch as a ceremony in which “it is not even a matter of giving and returning gifts, but of destroying so as not even to appear to desire repayment.”1 Such destruction, such consummation, such an expense that cannot be repaid becomes precisely the source of the recognition that legitimates authority. Through the potlatch, the colonizer can transform his urge—for enjoyment, expenditure, and the consumption of land and body—into power. It is through the potlatch that exploitation can be constituted as state policy, always foreshadowing for the settler a final exploitation, an orgasm, a totalizing gift from which the name and nation will finally be born. The Father would be born from a gift impossible to repay, one that ultimately legitimizes and redeems the law. However, the potlatch that feeds the law and Brazilian sovereignty is always a potlatch in debt. However extravagant it may be, it is never enough, because it is always compared to the ghost of the law that colonizers and settlers are unable to forget: the Father from whom the Brazilian psyche flees, but whose simulacrum of unquestionable will still imposes itself.

In this way, Brazilian authority becomes trapped in producing potlatch after potlatch, transforming its legitimacy into a promise while constantly governing in the name of the exception, in the hope of consumption and expenditure, of enjoying a sacrifice so extraordinary as to erase its spurious and deficient character. It is this debt that allows the colonizer to coexist with the settler insofar as the colonizer can continue to explore, consume, and enjoy through the potlatch, and the settler can see in the colonizer’s enjoyment and expenditure the future birth of law and name. And yet, this birth is always postponed because the authority is burned, inevitably consuming itself in the fire of expenditure, from which the farce of hope and name must be restored with new clothes. It is no wonder that novelist and poet Machado de Assis deftly noted about the 1889 Proclamation of the Republic and its positivist slogans that “you change your clothes without changing your skin.”2 Clothes burn in the manufacture of the gift, yet the skin of settler and colonizer remain because it is made of absence.

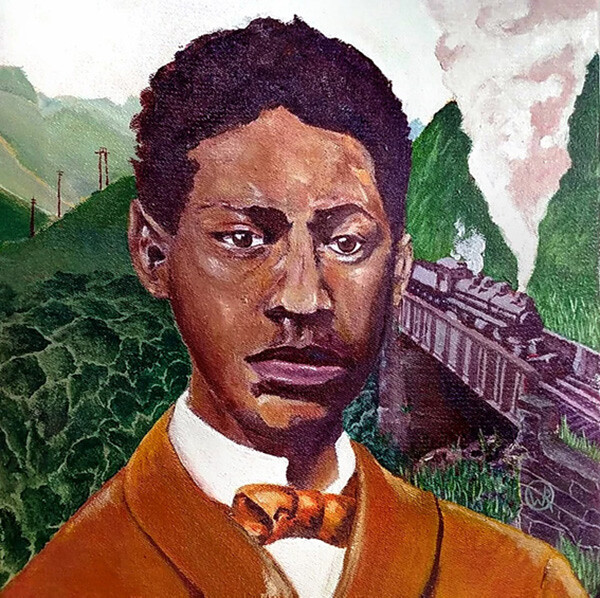

Portrait by André Rebouças, William R. Quintal, 2020.

It is curious that the new republic put on its military uniform precisely when the disastrous Brazilian Empire contradicted its own logic of exploitation and enjoyment by turning what were legally things into subjects with the abolition of slavery. This brief moment exposed the wound in which the nation is manufactured. The settler who supposedly always asked for law and order, for a name and a Father, could make abolition his skin, the beginning of the end of the colonizer’s logic. The settler could use the gesture to replicate the transformation of Brazil into a Brazilian subjectivity, to finally give himself a name and make a country. But the settler is always a colonizer; and between them, there is a permanent state of confusion that can only beckon and renew the potlatch, since the colonizer can only see in exploration and autophagy the possibility of finding himself. Abolitionist André Rebouças’s statement that the Republic was proclaimed against the 13th of May (the day Brazil abolished slavery in 1888) is fair; after all, the Republic was proclaimed mainly to renew the possibility of being a colonizer with different excuses.

From positivism, “order” and “progress” remained on the Brazilian flag next to the abandoned temple in downtown Rio de Janeiro, remnants of a mimosa tree in which settlers and colonizers hid to start a new cycle, promptly followed at the end of the nineteenth century by Ruy Barbosa’s schizoid liberalism, the caudillismo of Floriano Peixoto’s strongarm leadership, and the genocide of Canudos, always anointing order and progress while continually surrendering—whether in misery, blood, or gunpowder, the incomplete enjoyment of an intermittent baptism. This baptism permeates the wealth of the coffee barons, the scars in the sugarcane fields, and the pau brasil torn by its roots, from a place where one is born without discovering satiety nor name.

Survivors from Canudos, 1897. License: Public Domain.

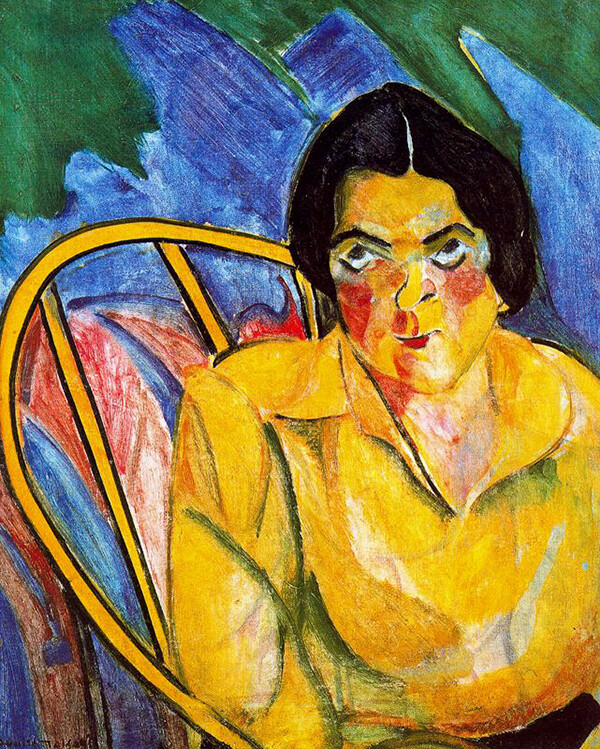

These earlier scars would appear to foresee the famous reaction of Monteiro Lobato, the writer par excellence of the decadent coffee aristocracy—and the embodiment of the confusion between settler and colonizer—when he came across the first sketches of Brazilian modernism in the work of Anita Malfatti. His 1917 article asks right in the title: “Paranoia or Mystification?” Soon after, he will frame Malfatti as an artist who sees nature “abnormally, and interprets it in the light of ephemeral theories, under the squint-eyed suggestion of rebellious schools, emerging here and there like boils of excessive culture.”3 Lobato’s reaction comes from the fact that what Oswald de Andrade described in his Pau-Brasil manifesto was already in the contorted nose of Malfatti’s 1916 A Boba (Silly woman): “A single struggle—the struggle along the way. Let’s break it down: Import poetry. And the Pau-Brasil Poetry, for export.”4 The struggle of Pau-Brasil poetry is, above all, to become just like pau brasil wood, to become the object of exploration, to mix with the other and make it yours. The nose of the lady deformed in Malfatti’s ink and absorbed in the canvas is a cry to become just a body, no longer living for pleasure or in hope of a name, but only for voracity. Brazilian modernism presents itself as the paranoia of both settler and colonizer in the mystification of finally becoming Brazil, becoming a body without a name or interdiction, a body of alterity, a body without skin and only of pores that devour subject and world, rendering everything the same tropical utopia.

Anita Malfatti, La Boba, 1915. Courtesy of Museum of Contemporary Art, University of Sao Paulo, Brazil

The impulse of the Week of Modern Art of 1922 is an impulse beyond the division of the modern. This impulse marks all and any modern art, in the prophecy of a discovered totality. In order to make Brazil a totality, from 1922 onwards some ventured to devour the mimosa that hid the divided sign of colonist and colonizer, forgetting the lesson of Homer’s lotus eaters. If the Greeks discovered sleep in the lotus, then it was inside the mimosa that the beast and its lips of blood awaited, awakened.

3. Rubídea (Redness)

Of the many European testimonies born from the encounter with the New World, none has the frankness of Michel de Montaigne in his Of Cannibals (c. 1580). Already anticipating the anthropology of the twentieth century by denying the stigma of savagery, Montaigne confronts the notion of civilization by refusing the period’s popular conception of natives as people without salvation, or as barbaric enemies. Faced with a way of life doomed to annihilation and the possibility of true barbarism originating from Europe itself, Montaigne had little of the plaintive nostalgia found centuries later in Tristes Tropiques, where Claude Lévi-Strauss’s writes that

from the day when he first learned how to breathe and how to keep himself alive, through the discovery of fire and right up to the invention of the atomic and thermonuclear devices of the present day, Man has never—save only when he reproduces himself—done other than cheerfully dismantle million upon million of structures and reduce their elements to a state in which they can no longer be reintegrated.5

Lévi-Strauss’s words resonate with the climax of Montaigne’s confrontation, which, supported by the cultural relativism of the text as a whole, shamelessly legitimizes the cannibal. And rather than do so explicitly, Montaigne lets the native victim himself, the one who will be eaten, speak in the text: “Come all, and dine upon him, and welcome, for they shall withal eat their own fathers and grandfathers, whose flesh has served to feed and nourish him.”6

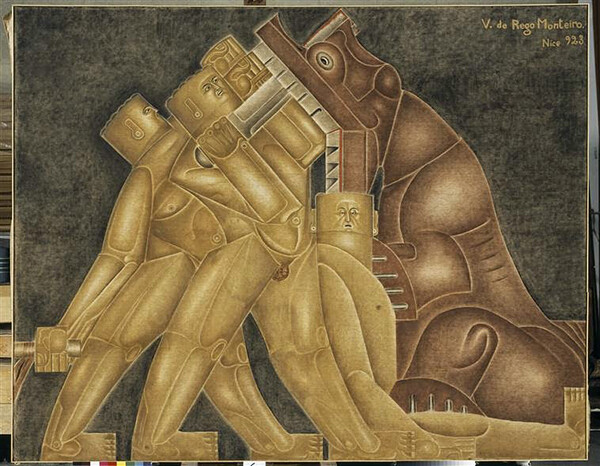

Vicente do Rêgo Monteiro, The Hunt (A Caçada), 1923.

In the speech of Montaigne’s cannibal, who understands his flesh as a mere bridge, it is possible to find the tears of the Tupinambás in their welcoming ceremonies with which Derrida opens his essay on hospitality. Tears “associated with a cult of the dead, the stranger being hailed as a ghost.”7 Cannibalism is part of the same dynamics of encounter, of hospitality that transforms the other into the self through the very dead matter that strips away the individuality of a body, and that is a vehicle for several. Montaigne emphasizes that the natives he knew in France Antarctique (today called Rio de Janeiro) had a way of speaking that divided men into two parts.8 It is in this game of halves that the unity given by the flesh is a vital fragment, merging life and death through the mouth to make past time, divided and hidden, flow back. Cannibalism here is a gesture of temporal and radical hospitality that seeks through dead matter to revive an impossible totality—to transform the subject into an open and manufactured body that, while part of an infinite process of devouring and digesting, has no end or limit. The radical consequence of this cannibalism, at once autophagic and self-fertile, is a conception of time that also knows no end or beginning. Continuously renewed from each death and fragment on the margin of European history, such a conception of time promises that the world is always about to begin—and end.

If on the margins of history the fragment renews itself, inserted within Montaigne’s time and his promise it becomes a sign of decadence and ruin. This is the main characteristic of the work of art born from the world after contact with the Americas: “The image is a fragment, a rune … The false appearance of totality is extinguished.”9 The Baroque allegory is a symptom of a cosmic vision torn apart through contact with someone other than me in a world that expands as it grows tired of waiting. Lost in seas and machines alien to salvation, it is abstracted from the self: a symptom of history without the possibility of redemption, a history without God or synthesis.

Benjamin explains that the Baroque allegory is a reminder of the skull, in which the odor of destruction coexists with the maintenance of the human form. It is as though the desperate choice was between obeying God along with the kings and queens that promise to preserve man’s eternal character, or being condemned to ashes of things. This choice is nothing more than the choice between becoming an object in a world without God or remaining a subject in waiting. This is the only Baroque drama that Hamlet enacts, contemplating the skull that terrifies him and from which he cannot escape: he too will become a fragment, he too will become a thing. There is no hospitality between these two poles. Unlike the flesh on which the cannibal gorges himself, the skull does not speak the name of the mother, father, or grandfather. It only renews the silence of history in its bureaucratic process of Man’s condemnation.

Benjamin writes about Baroque allegory mainly to understand and validate the origins of the avant-garde artwork of his time, provoking the same rupture in the model of formal unity in favor of the fragment. In fragmentation, the avant-garde precisely unveils the work of art as a thing and as a technique. But as Benjamin understands this fragmentation, it gradually passes from suspension and analysis to become a source of “profane illumination.”10 In the initial moments of his first surrealist manifesto, André Breton already states that “man, that inveterate dreamer, increasingly discontented with his fate, finds it difficult to evaluate the objects he has been led to use.”11 If Breton’s manifesto and the surrealist movement start from this divorce between subject and object, from their total dissonance and incompatibility, from the thing-character of the work of art, they are based on an incessant appeal to make this world of dead things and profane things speak to Man through the alphabet of desire.

The price for this desire between subject and object, between man and art, is, however, to radicalize the self beyond the limits of a rationality that organizes things by a utilitarian logic. It is to reach the threshold of the very idea of a thing that ceases to be a means and becomes a reflection. This justifies the obsession with the dream—the search for a zone of reality beyond the tombstone of the utilitarian organization in which reason itself is sustained, a zone where it is possible to change “the human facets for the face of an alarm clock.”12 Stripped of utilitarian ties, far from the Enlightenment that necessarily turns every object into a tool, the surrealist cuts away at the world and its things under the auspicious and solitary curatorship of the libido that no longer analyzes, but instead desires.

In the first surrealist manifesto, Breton speaks of transforming himself “into simple receptacles of so many echoes.” At the same time, he says that “man proposes and disposes. He and he alone can determine whether he is completely master of himself, that is, whether he keeps the body of his desires, each day more formidable, in a state of anarchy.”13 In its first systematization, the movement is already immersed in the ambiguity between wanting to be a receptacle of the profane world and, at the same time, its inventor. A Heliogabalus anarchist and king, the surrealist is the God of his own liturgy, of the vision of his prophecy that, in his search for the world, only finds himself everywhere, producing the magic and effects with which he is dazzled. Like a neurotic on the couch, he struggles under the island of the self. The recording instrument in which he is cross-dressed never remembers more than the scream of a skyscraper, never the primary noise, but an echo covered by infinite layers of desire for another, for a world beyond its continuous collage of self. When Breton says that the most real phase of life is childhood, the child here can at most be a memory of the mirror phase, and never the intended playful integration between being and world. Whatever the intensity of desire, this integration is forever closed.

Breton seems aware of this when he indicates dialogue as the form of language that most closely aligns with surrealism. According to him, in the surrealist dialogue, the interlocutors

simply pursue their soliloquy without trying to obtain any special dialectical pleasure from it and without trying to impose anything on their neighbor. The remarks exchanged are not, as is usually the case, intended to develop some thesis, however unimportant; they are as discontented as possible.14

It is precisely by balancing the desire for profane illumination and the certainty of its discontent that surrealism and its alleged dialogue between being and world, subject and thing, is, above all, camouflage. In this way, the surrealist claims that the beach is under the cobblestones as if selling canned goods with increasingly short expiration dates.

It is no coincidence that the second issue of the anthropophagy magazine edited by Oswald de Andrade declares: “After surrealism, only anthropophagy.”15 The most radical systematization of Brazilian modernism doubles down on the surrealist collage. Anthropophagy interrupts the lines of dialogue, abdicating the desire to be a vate, or enlightened prophet, to say: “I’m only interested in what’s not mine. Man’s law. Cannibal law.”16 Oswald de Andrade’s operation seeks to revive the gesture of hospitality of Montaigne’s cannibal, to insert his flesh and especially that of the country into the infinite process of devouring and digesting where any lines between human and thing are erased. In favor of the fusion given by the appetite that no longer sees distinctions, everything serves to be devoured. Everything is fragmented flesh, including Oswald de Andrade himself and the modernists who fade away amid their voluptuousness. The fundamental question becomes only evoking and, above all, subverting the Baroque drama of Hamlet through the native Brazilian heritage of the Tupi tribe: “tupi or not tupi?”17 Resurrected, the cannibal transcends not only being and nothingness, not also the borders between the world of men and the world of things. He takes from the flesh of the other, from the lost and found world, from what Brazil never had: time.

Victor Brecheret, Head of Chrtist, 1950.

It is time that flows through the braids of Victor Brecheret’s Head of Christ, his open mouth, his phallic form, a Christ without cross or promise, a Christ without race, a Christ of life and permanent joy, a body of Christ that lives and proclaims Brazil through immemorial times that turn Brasilia into Judea. Pregnant time, gushing like milk from the exposed breast of Tarsila do Amaral’s A Negra (The Black Woman), inventing in ink a story where everything begins in that breast, not enslaved but divinized as origin and encounter, as if there wasn’t so much blood between America and Africa. There is still so much time in the famous aí que preguiça (how I am lazy) of Mário de Andrade’s 1928 novel Macunaíma—Brazilian modernism personified—which roams the jungle and the city, changing shape and race to be one from many, to finally give a body and a breath to the country between Christ and Tupã. In these works, Brazilian modernism, in its most brilliant moments, realizes Oswald de Andrade’s utopian maxim: “Only anthropophagy unites us.”18 In these works, almost by a miracle, Brazil is not the now that its modern settler and colonizer think about being born and condemned to. Instead, it is a transhistorical, eternal, and tender body, multiple and open. It is filled with new and old colors and names that devour each other without ceasing to belong to the same fabric of past, present, and future. In these rare and brilliant moments, Brazil exists beyond momentary enjoyment or interdiction. It is not mere history or promise, but invented as if it was always there.

The tragedy of Brazilian modernism is that these brilliant moments of paint and words do not sustain themselves. They never leave pages and pictures because devouring implies being a body, and being a body also implies being devoured. Contardo Calligaris says, “To reduce oneself to a body is to give oneself to whoever wants to enjoy us.”19 From this perspective, the modernist gesture of anthropophagous revival becomes as innocuous as the words of Montaigne or Lévi-Strauss, watching the end of a way of life. It reproduces the same tragedy of colonization in which Indigenous people stretched out their hands and had their arms cut off. One can no longer be Tupi because one became Brazilian without knowing it, because devouring no longer renews time but instead means merely self-violation and self-abandonment. The aesthetic project resists; it is celebrated and lauded, but anthropophagy as a national signifier is fragile, easy prey. It only produces a more voluptuous body for the colonizer, for the consumer, and perhaps here the criticism of the aristocratic and bourgeois origins of the modernists touches too deeply on their carnage and absence.

Maybe this has never been so well illustrated as at the end of Joaquim Pedro de Andrade’s 1969 film adaptation of Macunaíma, where Macunaíma—the modernist hero who changes shape, body, and face—does not become a constellation; the body that devours does not integrate into the cosmos (as in the book), but is instead also devoured. He is transformed into a pool of blood, with all his wealth of signs, symbols, and forms that he had collected through devouring, which become blood too. In the ultimate end of anthropophagy, the cannibal does not build a transhistorical body for the country. He and the country become the same pool of blood; the ultimate end of the impossible anthropophagous digestive tract is a vacuum.

The Modern Art Week of 1922 did not give birth only to the cannibal. While Oswald de Andrade spoke of Pau Brazil poetry and advocated transforming the country into a body that devours the foreigner, at the same time the gloomy figure of Plínio Salgado drew flags with tapirs and sketched the first traces of Brazilian fascism. If all modernism starts from the desire for a totality that imposes itself on the splitting of the modern, Salgado did not want to be a body or an object; he ultimately wanted to be a father. This helps explain why his Integralismo became one of the most significant mass movements in Brazilian history. The green shirts, the flags fluttering with the Greek sigma, the Tupi Anauê greetings, and the nativist Catholic nationalist broth that Plínio conjured settle in the heart of the promise offered to the settler who, since 1500, asks for affiliation. In an extensive work of aestheticization, Plínio ends what Romanticism and its twisted nativism began: Brazil as a total subject.

The memory of Brazilian Romanticism is fundamental not only because of Salgado’s explicit adulterated nativism (whether in his Tupi Anauê chant or in all nationalist propaganda), but also because it is in Romanticism that, in a first effort to legitimize Brazilian national identity, Gonçalves Dias and especially José de Alencar metamorphosize the figure of the native into that of the medieval Christian knight. The “honored Indian” of Romanticism, whether in Dias’s poem “I-Juca-Pirama” or in Alencar’s novel The Guarani: Brazilian Romance, is struggling in the literary forms of the late nineteenth century to stop being an object of exploitation or the colonizer’s conversion, to be portrayed as a subject in the European mold, which means already possessing Christianity’s moral compass. The transformation of Indigenous representation in Dias and Alencar is ethical precisely in echoing the passage from land to a nation based on law. If the first son of the earth has the law of Christianity, the earth must have always had it.

The fascist Integralismo of Plínio Salgado will immediately recover this gesture in its greeting from the Tupi Anauê and in the declaration of its greatest enemy: cosmopolitanism. “Cosmopolitanism, that is, foreign influence, is a deadly disease for our Nationalism. Fighting it is our duty.”20 The duty of Integralismo is justified for Plínio by a scenario that puts the Brazilian way of life at risk: “Our homes are impregnated with foreign words; our lectures, our way of looking at life, are no longer Brazilian.”21 The implication is that true national identity has been lost in the absence of immunological responses. The confrontation between Oswald de Andrade and Plínio becomes apparent as the former proposes to embrace (devour) the lack of a national syntagma, and the other speaks of a lost identity that must be rebuilt. But like the Romantics of a century before, Plínio Salgado is somehow aware that Brazil never existed, that it is still necessary to discover it: “We, united Brazilians, from all provinces, propose to create a culture, a civilization, a genuinely Brazilian way of life.”22 His fascism, above all, needed this constant and individual aesthetic discovery. Perhaps for this reason, despite being popular, Integralismo never had political viability. It was condemned to be an auxiliary line of president Getúlio Vargas’s traditional Latin American populism, and to inspire the resounding failure of a minor insurrection.

Although many were willing to wear green shirts and shout the Tupi greeting, Integralismo was incapable of self-designing a past. The definitive law that Integralismo’s multitude had been waiting for so long to materialize did not come. Integralismo needed a collective effort to become a father or to syncretize Salgado’s aesthetic research, which was still a tropical Frankenstein and a disguised cannibal (just look at the Nazi and fascist influences that Plinío carefully collected on his visits to Europe). Despite its efforts, Integralismo could not escape the now where Brazil never really begins or ends. Like Alencar’s medieval Indian, Integralismo was never more than a paper tiger. In the end, when reality imposed itself, Integralismo abstained, not by choice but by duty, in accordance with its own totalitarian fantasy of annunciation.

Participants in the 1922 Modern Art Week at Hotel Terminus in São Paulo. From right to left: Couto de Barros, Manuel Bandeira, Mário de Andrade, Paulo Prado, René Thiollier, Graça Aranha, Manoel Villaboim, Godofredo Silva Telles, Motta Filho, Rubem Borba de Moraes, Luiz Aranha, Tácito de Almeida, Oswald de Andrade. Pphoto: Archives of Museu da Imagem e do Som.

Mário de Andrade, the writer of Macunaíma, twenty years after the Modern Art Week of 1922, wrote in his autopsy of the modernist movement that he perceived in almost all of his work “the insufficiency of abstentionism.”23 De Andrade’s autopsy is a sad one because it reports the distance between art and the world, which, in a way, is the same as saying that there is no world. After all, if art is already without threads for sewing, everything has already come undone. De Andrade says that after so long, he still seeks in his work and that of his companions “a more temporary passion, a more virile pain of life. There is none. There’s more an old-fashioned absence of reality in many of us.”24 Both Oswald de Andrade’s revived cannibal and Plínio’s father are in-vitro fertilizations—born, bred, and killed in museums. Whether in the terrifying pages of history or in beautiful galleries, its fragments, sometimes sensual, sometimes violent, lean over, attempting to devour the walls of cellulose and glass but never escaping the abstention in which they were created: the abstention of a country, the abstention of time itself, the abstention of already being modern.

The cannibal devoured in his own blood, in his own invocation of flesh; the father drowned in his endless aesthetic research of tapirs, Greek letters, the Tupi Guarani language, and violence; modernism and its beasts, its cannibal dream, its fascist nightmare as undeniable proof that it would not be possible to surpass Brazil as an eternal rehearsal of its own samba plot. What remains is an avenue through which the torture poles25 that make up our bones go on parade, looking for the end of the night where the pale ghosts of captains roam, staring back at us.

Continued in “We Too Were Modern, Part III: Of Earth and World”

Marcel Mauss, Sociologia e Antropologia (1950) (Cosac Naify, 2008), 239. All translations from Portuguese are by the author.

Joaquim Maria Machado De Assis, Esaú e Jacó (J. Aguilar, 1973), 79.

Monteiro Lobato, “Paranóia ou Mistificação?” →.

Oswald De Andrade, “Manifesto Da Poesia Pau Brasil” (1924), Buala, 2018 →.

Claude Lévi-Strauss, Tristes Tropiques (1955), trans. John Russell (Hutchinson & Co., 1961), 397.

Michel de Montaigne, “Of Cannibals” →.

Jacques Derrida, “Hospitality,” in Acts of Religion, ed. Gil Anidjar (Routledge, 2002), 359.

Montaigne, “Of Cannibals.”

Walter Benjamin, The Origin of German Tragic Drama, trans. John Osbourne (Verso, 1985), 176.

Walter Benjamin, “Surrealism: The Last Snapshot of the European Intelligentsia,” in Critical Theory and Society: A Reader (Routledge, 1990).

André Breton, Manifestoes of Surrealism, trans. Richard Seaver and Helen R. Lane (University of Michigan Press, 2012), 3.

Benjamin, “Surrealism.”

Breton, Manifestoes of Surrealism, 27–28, 18.

Breton, Manifestoes of Surrealism, 35.

Cunhambebinho, “Péret,” Revista de Antropofagia 1, no. 2 (1929).

Oswald de Andrade, Manifesto Antropofago e Outros Textos (Penguin, 2017).

Andrade, Manifesto Antropofago e Outros Textos.

Andrade, Manifesto Antropofago e Outros Textos.

Quoted in Andrade, Manifesto Antropofago e Outros Textos, 36.

Plínio Salgado, “Manifesto de Outubro de 1932” →.

Salgado, “Manifesto de Outubro de 1932.”

Salgado, “Manifesto de Outubro de 1932.”

Mário de Andrade, Aspectos da Literatura Brasileira (Livraria Martins Editora, 1972), 253.

De Andrade, Aspectos da Literatura Brasileira, 252.

Pau de arara (macaw’s perch) is a torture technique in which the victim is tied up and forced to hang from a pole by their bent legs. The technique was widely used by during Brazil’s military dictatorship (1964–85).