Preface to the English-Language Edition1

This book brings together six seminars on operaismo held between January and February 2019 at Mediateca Gateway, a library and center of political and militant formation in Bologna, Italy, which has now become .input. The title of the course, “Futuro Anteriore,” was taken from a book published by DeriveApprodi in 2002—the result of a project of co-research whose point of reference was Romano Alquati—which includes roughly sixty interviews with people connected to operaismo.2 The subtitle of that book, Dai “Quaderni rossi” ai movimenti globali: Ricchezze e limiti dell’operaismo italiano (From “Quaderni rossi” to the global movements: The wealth and limits of Italian operaismo), anticipates the political method that will be used here.

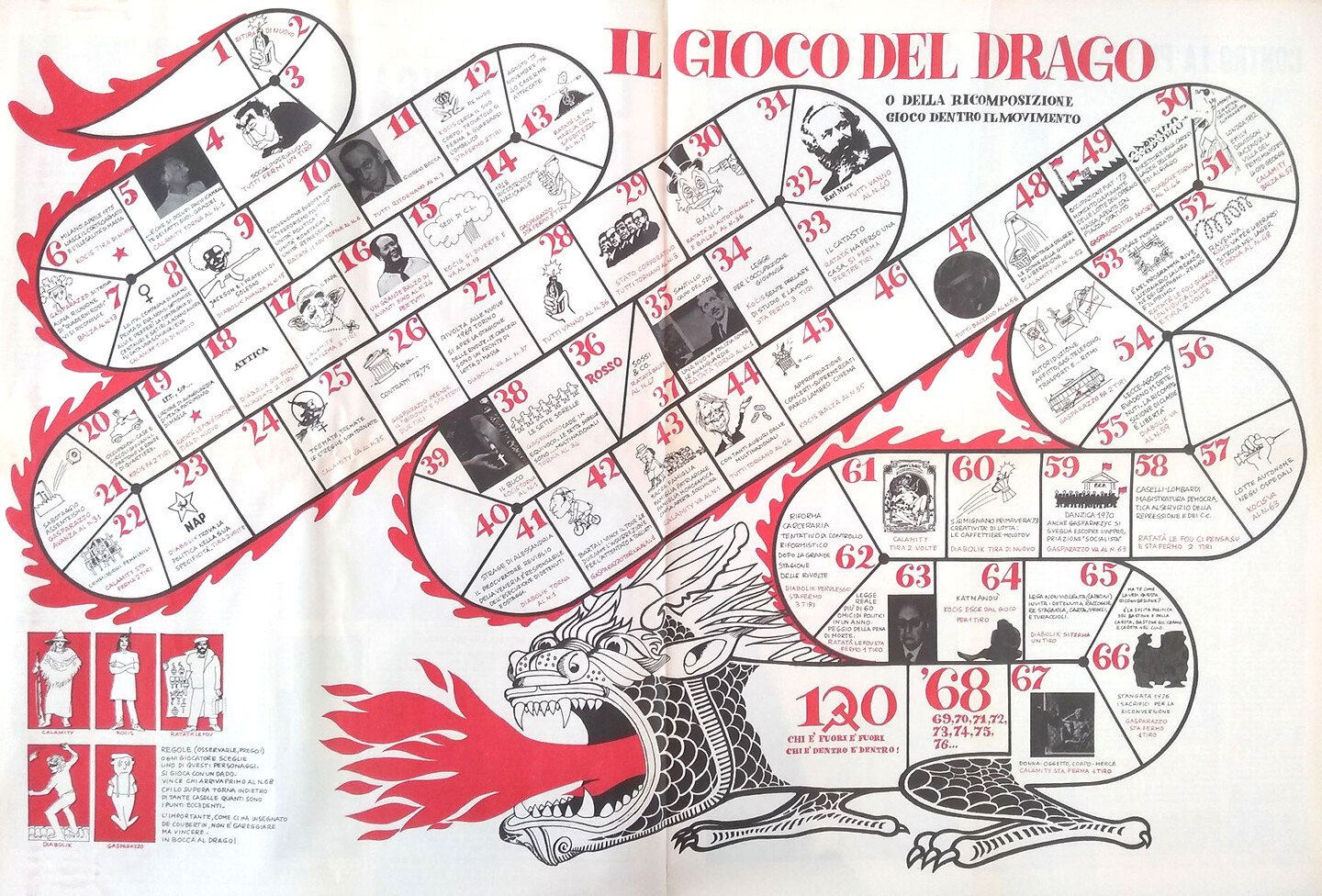

Cover of Quaderni rossi, no. 1.

Now, as then, tracing the history of operaismo doesn’t mean celebrating an icon or fixing an orthodoxy. Despite its “-ism,” operaismo always refused ideology and any loyalty to sacred scriptures. This began with its radical rereading of Marx and Lenin against the Marxism and Leninism that was dominant in the social-communist tradition, in both its Stalinist and so-called heretical versions. We will revisit that history, our history, to overturn it against the present: not to contemplate it but to set it alight. To appropriate its wealth, to fight against its limits, to transform it into a political weapon. Not because continuity is possible, but because for us discontinuity means assuming the operaist point of view of partisan collectivity on and against this world. We must reject both the exaltation of the new and nostalgia for the past, the desire for the “post-” or the “pre-,” as they are two sides of the same coin.

The term “militant formation” (formazione militante) should be clarified to avoid misunderstanding. It has nothing to do with indoctrination, based on ideological transmission, or with education, based on the transmission of preestablished values. On the contrary, it is a process of constructing a point of view and a capacity for critical reasoning, of being able to continually call into question or subvert the knowledge being formed. For a revolutionary militant, the point of view is an indispensable premise and at the same time that which must be continuously fought for. When we no longer have it or search for it, as premise and as conquest, we stop being militants. Today we are faced with the problem that most political militants have stopped engaging in militant formation and critical reasoning. In periods like this, then, in which we are unable to glimpse any possibility of radical transformation on the surface, there is a widespread tendency to flee into ideology, or into the values of microcommunities, seen today in the “bubbles” of political activists both on social networks and in real life. This consolatory form perhaps allows us to endure the current reality, but certainly not to fight it. In fact, the closest ally of that reality is everything that allows it to be endured by those who could or would like to fight against it.

The people who participated in the course—about thirty comrades from different generations, although mostly young—did so not to imbibe the words of the sacred scriptures but to find tools for rethinking the present, to dive down into the obscure ambivalences that bubble beneath the surface. Their contributions and questions were decisive in the spiral construction of the course, whose discursive style we have chosen to maintain here. For the sake of the fluency of the text, they have not been transcribed as interventions, but are directly incorporated into its development.

This explains one of the two reasons why the first-person plural is used and not the singular: it was a collective process. The other reason is that a militant is always a collective individual; when you go back to thinking, and thinking of yourself, as an “I,” you cease to be a militant. The process of militant formation reaches the point where the individual both speaks and is spoken of from the point of view, in the sense we have alluded to and will elaborate on: not as a dogma, but because the point of view guides the way we see every aspect of the world and situates us within and against it. In other words, the militant is always part of a collective process; their subjectivity is formed through struggle against the modern individual, the abstract egoistic and solitary subject of the liberal and democratic tradition.

Operaismo is our point of view, it is a method or a style, our Weltanschauung. It is an irreducibly partial point of view, an irreducibly conflictual point of view, in relation to both the world and ourselves. Because in order to fight the world in which we live we must at the same time and continuously fight the world that is embodied in us, that produces and reproduces our lives, our way of seeing, our subjectivity.

In the last twenty years or so there has been a rediscovery or, perhaps more accurately, a discovery of operaismo on the international level. Since the publication of Negri and Hardt’s Empire and the diffusion of its categories and lexicon in university departments across the world—where it has taken on the label of “Italian Theory” or “post-operaismo”—that revolutionary and irreducibly partisan political thought has definitively left the Italian province. But, in the process, it has been watered down and deprived of what made it revolutionary and partisan. The global university is an extraordinary machine of depoliticization: you can say whatever you want, as long as nothing you say affects the relationships of domination. This form of freedom neutralizes the radicality of thought, rendering it compatible with and functional to the machine of accumulation: the problem is not the absence of freedom but the liberal form of freedom. Thus, for reasons that will be explained in the text, that prefix—the “post-”—has engulfed the noun, neutralizing the method.

But be careful. This book does not set out to explain the “true” operaismo. For revolutionary militants, truth is never something that needs to be explained, but is always something that must be fought for, just like the point of view. Everything that is needed to fight the current reality is “true,” everything that isn’t needed isn’t “true.” In this book, then, readers will find themselves confronted with the radicality of operaismo in the literal sense: that is, the ability to get to the root of things, to grasp it, to try to tear it out or overthrow it. And the root is not underground, as you might think, but actually at the top, in the central points and contradictions. This requires a posture that isn’t in thrall to fashions or dragged into the ephemeral vortex of public opinion. It means criticizing what everyone else accepts, also on a conceptual level. And it means criticizing what is accepted not only in the mainstream but also and above all in activist communities.

To give one example among many, we might think of the term “intersectionality,” which has become fashionable in these circles. Here class disappears as a central contradiction and as conflict, being reduced to an economic fact that becomes one of the many identities located on a horizontal line, an identity of fragments in which every individual or small group can feel recognized in the hierarchy of subalternity. These identities are potentially infinite, much like the market. The sum of these fragments is never recomposed, or rather is always recomposed by capital. And so, having gone out the door, the old Marxist economism reenters through the window of intersectional identities, together with various other “-isms.” This book will explain why the operaist concept of class composition already anticipates by many decades the best critiques of intersectionality, insofar as gender and race dynamically and continually redetermine that composition. From the political point of view, class is composed through struggle and conflict, not on the basis of objective identities. It is not the exploited and the subaltern who compose themselves as a class, but those who struggle against their exploitation and subalternity. As Mario Tronti says: there is no class without class struggle. In the same way, the critique of universalism and historicism that has been so fashionable since the 1980s was practiced and anticipated by operaismo in a completely different direction, beginning from the irreducibility of the partisan point of view, and not—as was the case in the era of capitalist counterrevolution—from the end of the grand narratives with which the lexicon of the “post-“ has endorsed the prohibition of the very conceivability of revolution. And the revolution means civil war, that is to say, the class struggle at the highest level of intensity. The operaist polemos is always the strong thought of subversion, never the weak thought of cultural and political relativism.

In short, the reader will find no room here for liberal pluralism, in which everyone can get together in the name of the general interest—including the general interests of community micro-identities. Because the general interest is always the interest of capital, and when everything is held together, it belongs to the bosses. On the contrary, the operaist method is, first and foremost, divisive. One side against the other; either you’re on one side or you’re on the other. And because of its formative character, this text will not give the reader ready-made answers or easy solutions; there will be no peace and quiet. Operaist formation uproots acquired convictions to get to the heart of the problem, for it is there, in that heart, that we must collectively and continuously reconstruct our capacity to be against. This is an act of force, of violence, that tears us away from the quiet management of our existence. Only those who are willing to be disturbed by this problem can open up the possibility of solving it.

Thus, the invitation we make to our readers is—as Alquati, one of our “tutelary deities,” used to repeat continually—to use this book like a machine, not passively, but by acting to make it come alive, that is, as a tool that can be transformed to abolish the present state of things.

Chapter 1: Context and Specificity: The Breeding Ground of Italian Political Operaismo

We can say from the start that operaismo is unfashionable or, to use a Nietzschean term to which we will return, “untimely.”

Our next question is whether operaismo had anything to do with the glorification of factory workers as factory workers. We should first point out that other workerisms existed during the 1900s, and we will briefly summarize the main examples.3

Wojciech Fangor, Forging the Scythes, 1954. Courtesy of Museum of Warsaw.

First, there was councilism, which was at its strongest in the 1910s and 1920s and was based in the experiences of workers’ councils or soviets. Some concrete examples include Rabociaia Oppositzia (Workers’ Opposition) in the Soviet Union, whose most significant leaders were Alexandra Kollontai and Alexander Shliapnikov; Ordine Nuovo in Italy, centered in Turin, which included Antonio Gramsci; the German groups linked to the insurrection of the workers’ councils at the end of the First World War;4 and, among many other militant thinkers, the Dutch theorist Anton Pannekoek.

The central figure in the councilist movement was the craft worker (operaio di mestiere), considered to be better than the bosses at keeping the factory going. This leads to a vision of the self-management of the factory and society by workers united in the collective form of the council. Thus, councilism involves the glorification of the figure of the worker as such, a work ethic that isn’t simply ideology but is rooted in a specific class composition, in which this worker and their pride in their craft play an important role in the productive process. These workers bear the stamp of their predecessors, the artisans. They are a sort of split artisan, struggling to regain complete autonomy over their skills, capacities, and forms of organization. Councilism fights against the expropriation of the crafts, which is implicit in industrial development, and tries to guide development toward a strengthening of the collective autonomy of the working class. To simplify, we could say that the councilist movement’s perspective on self-management doesn’t deny the tactical function of the party, but forcefully asserts the strategic hegemony of the soviet.

Lenin’s critiques of councilism are relatively well-known. His text “Left Wing” Communism: An Infantile Disorder, which is now more often cited than read, was used in the decades that followed by various communist parties (including the Italian Communist Party) as an argument against all forms of class autonomy. We would instead recommend reading the debate on the function of trade unions in the Soviet Union between 1920 and 1921, a few years after the Bolsheviks took power; and three lectures held in 1967 in Montreal by the Black communist C. L. R. James, which were dedicated to this subject.5 We will now briefly summarize that debate. On the one hand, Lenin argued against Trotsky and Bukharin, who, coming from a bureaucratic perspective, wanted a complete statalization or even militarization of the trade unions, reducing them to a means for transmitting Soviet power. On the other hand, he heavily criticized Workers’ Opposition for their naive democratic ideology: it was as if they thought that workers’ control was a natural point of departure rather than a process to fight for. We would say, perhaps forcing the argument a little, that the questions of workers’ autonomy and the extinction of the state are central to the debate on the function of the trade union. Trotsky and Bukharin denied them; Workers’ Opposition hoped for them as if it were simply a question of ideological will. But for Lenin they were important strategic stakes in the struggle, the fruit of a political process made up of conflict, organization, and the overturning of the relations of force. In this sense, it was precisely in that particular historical period that the trade union was not what it had been before and was not destined to be what it would later become: it would have to be used tactically, as a school for class struggle and for the development of workers’ autonomy, toward the extinction of the state.

Also at stake in this debate was the relationship between the soviet and the party, or rather, the old question of spontaneity versus organization. For Lenin, it was indeed a relationship, and so never given once and for all. This can be seen in his continually changing point of view between 1905 and 1917: there are periods in which spontaneity is more advanced—as happens with the revolutionary process after the Bloody Sunday of January 1905 and with the soviets between February and July of 1917. In these cases, organization had to follow spontaneity, rethink it, and reform it by beginning from it. There were other periods, such as between July and October 1917, in which the party had to reinvigorate the soviets that were at risk of falling into a stagnant democratic parliamentarism. In these cases, organization was used to reopen the way for the full development of spontaneity.6

In addition to councilism, there was another workerism of a very different, or even opposite, kind: the Stalinist workerism of the 1930s. In this case it was not the soviets that were central, but the party.7 However, the working class played an important role, being used against the intellectual and peasant petit bourgeoisie. Although it was a symbolic and instrumental reference, it produced concrete effects, both in terms of workers’ participation in the managing bodies of the party and, most importantly, in the exchange between obedience to the regime and relative technical autonomy. Rita di Leo describes it as something like a pact between the party-state and the workers, which guaranteed power to the former and a certain role in managing the pace of work to the latter, in apparent contradiction with the Stakhanov myth. But the contradiction is relative: the slow pace of production in the Soviet factories, which would continue in the following decades, was in fact a concession made in exchange for the symbolic role that the working class played in Soviet ideology—glorifying the proletarian condition and labor as something to be extended, not abolished.

Unlike Marx, who saw being a productive worker not as a blessing but as a misfortune, the Marxist and social communist tradition saw it not as a misfortune but as a blessing, and one that should be generalized across the whole of society: the bright future was to be painted in the gloomy colors of labor and exploitation.

After this long but necessary premise, we approach the theme of our chapter: context and specificity. Let’s begin from the context: Italy in the 1950s was a political desert, in which any genuine revolutionary perspective had been abandoned. The partisan resistance to fascism had become an icon: the mythicization of that experience was directly proportional to its depoliticization. The iconization of the Resistance in the popular imagination helped the Communist Party put an end to it in the reality of the class, in the same way as Napoleon’s celebration of the French Revolution was the final nail in its coffin. The more that something is sanctified as heavenly, the more difficult it is to repeat it on earth.

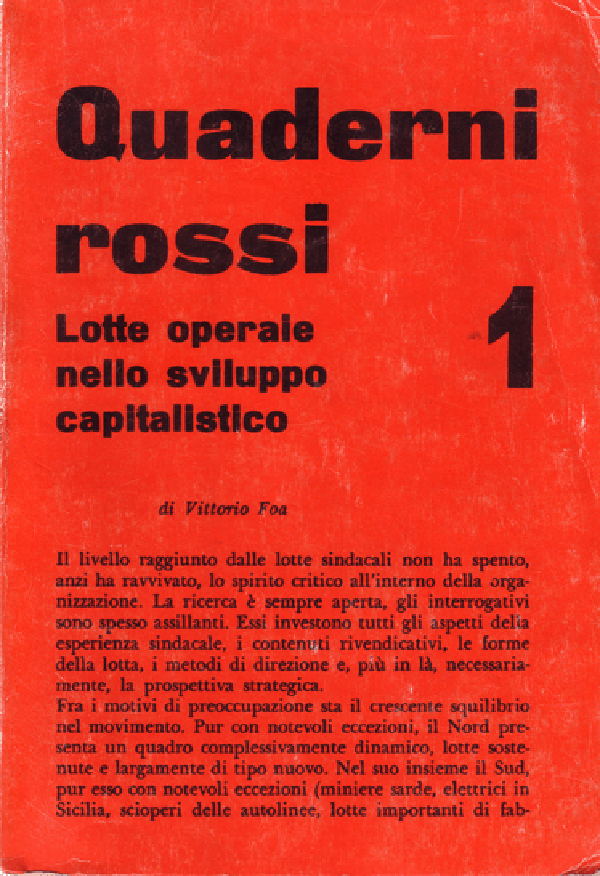

Mario Mariotti, printed in Classe operaia, no. 2 (January 1964).

The political desert of that period was visible in the factories. In 1955, the Communist Party–affiliated Italian Federation of Metalworkers (FIOM)8 was defeated in the elections for FIAT’s Internal Commission, which represented the workers’ trade unions in the factory. It was both a shock to the Italian Communist Party (PCI) and seen as a confirmation of its long-held and mistaken realism, in which the working class was considered to have lost all revolutionary potential. This led the party in a new direction: the pursuit of the middle classes and the “Italian road to socialism,” which in the 1970s would become the search for the “historic compromise.”9 This created a vicious circle: the leaders of the PCI, who held that the working class was finished, asked the communist and unionist cadre what was going on in the factories, who told them that nothing was happening, which just confirmed what they already thought at the top, further reinforcing their strategy. The PCI’s position, which had been built around its own interests, was a sort of Frankfurtism before its time. It wouldn’t be long before it was widely accepted that the Western working class had inevitably become integrated into capitalism’s iron cage. What’s more, at that time, not even sociology, which in Italy was still pretty insignificant, was interested in the factory (with a few exceptions, including the work of Alessandro Pizzorno on the experience of Olivetti in Ivrea).10

However, from the point of view of the relations of production and the organization of work in Italy, the 1950s were particularly significant. Lagging behind other Western countries such as the United States and Germany, it was only in this period that Italy experienced the full development of Taylorism-Fordism.

Taylorism is a model for the organization of factory labor, Fordism is a model for the organization of workers in society. Taylorism-Fordism mapped out the coordinates of the factory and society in which workers lived and were exploited, which would be further developed in the welfare state politics of the following decades.

We must keep this bigger picture in mind in order to avoid falling into the idea that there was an inevitability to the birth and development of Italian political operaismo. Not only was there nothing that allowed it to be predicted, but it was also in some sense “untimely.” We come back to this word, whose Nietzschean use we hinted at before: untimeliness is acting against time, on time, and for a time that is to come. Not outside time, but within and against time. Not an idealist action but a materialist one. There is no trace of utopia, of yearning for another possible world: it instead echoes Lenin’s “We should dream!” in What Is to Be Done?, refusing to accept the time we are given, in order to instead construct our own time, an autonomous time, produced through struggle and opposition.

For the Italian communists the 1950s were also marked by international events, in primis their relationship with the Soviet Union. Important events include the 1953 workers’ revolt in East Berlin, the Hungarian insurrection between October and November 1956, and, in February of the same year, the 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, in which Stalinism and its cult of personality were denounced.

This was heartbreaking for the Italian communists. But their formal de-Stalinization did not correspond to a real de-Stalinization, and the tanks in Budapest were a reminder of that: the PCI wholeheartedly defended them, despite the trauma felt at its base. Some militants saw more possibilities for action within the Italian Socialist Party (PSI). Raniero Panzieri, a founding figure of Quaderni rossi, started out in the latter. Others moved to the PSI as exiles from the PCI, such as Alberto Asor Rosa in Rome, or from other groups, like Toni Negri in Veneto, who had started out with the young Catholics in FUCI (the Italian Catholic Federation of University Students).

However, in this period an antagonist and revolutionary political initiative that went beyond the institutions of the workers’ movement was pretty hard to imagine. So much so that, in the following decade, the comrades of Quaderni rossi and Classe operaia were often verbally and even physically attacked when they went to factory gates without the mediation of the party or the union, addressing their leaflets directly to the workers.

Obviously, the old minorities still existed, in particular the Bordigist and Trotskyist groups, characterized by their heavy critique of the course taken by the Communist Party, and ennobled by their opposition to Stalinism. These included militants who would later become important for operaismo, such as the Bordigist Danilo Montaldi from Cremona, the French Trotskyist journal Socialisme ou barbarie, and the already cited C. L. R. James, who also came from Trotskyism. These groups should be interpreted as symptoms of the fact that the communist movement was not entirely pacified. However, these communist “heresies”—save for the few odd heterodox exceptions such as those we have just mentioned—often ended up restoring Marxist dogmas rather than calling them into question. The critique of Stalin turned into a critique of anyone who strayed from the objective tracks of History,11 and thus into an attack on subjectivism in the name of a traditional determinism. This was more or less the destiny and essence of these heresies, denouncing those who deviated from the straight and narrow, aiming to return to the authority of the sacred scripts.

We can find other symptoms of a critique of orthodox Marxism in this period, which are even more important for us because they make up a significant part of the breeding ground for that subjectivity that gave rise to Italian political operaismo. For example, Galvano Della Volpe—a thinker initially formed in the tradition of Gentile’s idealism who then explicitly broke with him—taught in the faculty of literature and philosophy in Rome and had a strong influence on Mario Tronti, Alberto Asor Rosa, Gaspare de Caro, and Umberto Coldagelli, all of whom would later contribute to Quaderni rossi and Classe operaia.

We could continue to follow the major and minor genealogies of what would later become operaismo (for example, citing the experience of Danilo Dolci in Sicily and his appeal to “go to the people,” which was answered by several militants who would later become part of Quaderni rossi and Classe operaia, such as Mauro Gobbini and Negri).12 But we will not do that here. We simply want to emphasize the character of the 1950s as a period of transition. However, we mustn’t forget that it is only retrospectively that we are able to attribute a historicist and teleological character to that transition. In that period, on the surface we would have seen only dismay, chaos, and resignation. Reflecting on that together, we could say that the transition isn’t sent to us by History but must be won by acting against History.

We should now focus on the crucial common element that brings the future operaist militants together: fighting a sense of defeat, seeking out strength, putting the problem of a revolutionary rupture back on the agenda. Their biographies tell specific and different stories: there were those who, like the Roman comrades, largely came from the Communist Party group in the university and were searching for a different point of view, either in explicit rupture with the party or in order to push the party toward revolutionary positions; there were those who, like the Venetians, came from heterogeneous groups, from social Catholicism or the Socialist Party, and gathered in the struggle at Porto Marghera amid the rampant industrialization of the Northeast; there were others who, in Lombardy and Piedmont, felt—as Alquati said—“humiliated and insulted, marginalized and bitter,” as a result of their proletarianization or lumpen-proletarianization following the end of the Second World War. “This downfall was soon felt by me as ambivalent: as a great everyday tragedy, but also as a further liberation.”13

Even in their differences (here summarized in an extremely cursory way), these biographies demonstrate a rupture with the cult of victimhood that had always been a constitutive part of the Left and much of the social communist tradition. It was not passion for the oppressed that guided them, but the search for those who struggled against their conditions of oppression. It was not about laying low in resistance, but about building a plan for attack; not about pitying weakness but about identifying force. For the future operaist militants, this would also be a rupture with themselves, with their own subjectivities and personal histories. A rupture that opened the way to new encounters and new trajectories, to a history that would become collective.

This is an edited excerpt from Gigi Roggero, Italian Operaismo: Genealogy, History, Method, trans. Clara Pope (MIT Press, 2023).

On the operaist concept of co-research, see Devi Sacchetto, Emiliana Armano, and Steve Wright, “Coresearch and Counter-Research: Romano Alquati’s Itinerary Within and Beyond Italian Radical Political Thought,” Viewpoint, September 27, 2013 →.—Ed.

In order to distinguish Italian operaismo from other workerisms, the Italian word “operaismo” will be used throughout the text, with the anglicization “operaist” as its adjective. Those involved in operaismo will be referred to using the Italian word “operaisti.” The word “operaietà” will remain in Italian, and describes the subjectivity of the figure around which the working class is politically recomposed.—Trans.

For further information on the German experience we recommend the book La rivoluzione tedesca 1918–1919, with a preface by Sergio Bologna, and Bologna’s essay “Composizione di classe e teoria del partito alle origini del movimento consiliare” (Class composition and the theory of the party at the origins of the councilist movement) published in Operai e stato, which came out in 1972 as part of the series “Materiali Marxisti” published by Feltrinelli and edited by comrades at the Institute of Political Sciences in Padua.

Published in C. L. R. James, You Don’t Play with Revolution: The Montréal Lectures of CLR James, ed. David Austin (AK Press, 2009).

On this we recommend Toni Negri’s article “Lenin e i soviet nella rivoluzione” (Lenin and the soviets in the revolution), published in 1965 in the first edition of Classe operaia and translated as “The Factory of Strategy” in his book Factory of Strategy: Thirty-Three Lessons on Lenin (Columbia University Press, 2014). In this book we also find the formula “organization is spontaneity reflecting upon itself,” which closely echoes Romano Alquati’s definition of “organized spontaneity,” which he used to interpret the struggles in Turin at the beginning of the 1960s, and to which we will return later.

On this subject we recommend Rita di Leo’s L’esperimento profano (Ediesse, 2012).

The Federazione Italiana Operai Metallurgici (FIOM) is the metalwork sector of the Confederazione Generale Italiana del Lavoro (CGIL), the trade union linked to the Communist Party.

The 1973 historic compromise was a political alliance between the Communist Party and the Christian Democracy (DC) party, proposed by the secretary of the Communist Party, Enrico Berlinguer.—Ed.

Olivietti is a historic business based in Ivrea in the province of Turin, which started off by manufacturing typewriters. After the Second World War, businessman and intellectual Adriano Olivetti, bringing together elements of Fabianism and humanitarian and Christian socialism, developed the idea of a utopian community that would be both productive and harmonious, able to guarantee the development of society and the individual. His Movimento Comunità (Community Movement) stood for election and, more importantly, attracted many intellectuals, trade unionists, and experts who wanted to set up an innovative industry, based on the concept of a capitalism founded on technical progress and interclass harmony. While the Left, past and present, is lavish in its praise of the Olivettian “community,” Alquati saw it as a mystification, revealing the antagonistic reality and organized conflict within it. This partly explains both his problems with the Left and why he is remembered as a lonely and isolated figure.

We begin the word “History” with a capital letter when it is understood as a necessary teleological progression, which for the apologists of the current system ended with the triumph of capital, and for Marxists will evolve into socialism and, ultimately, communism.

For more in-depth discussions on this topic, see Gigi Roggero, Guido Borio, and Francesca Pozzi, Futuro anteriore (DeriveApprodi, 2002).

See the interview with Alquati in Futuro anteriore. This, like the other interviews mentioned below, are all on the CD-ROM that comes with the book; some parts of the interviews were then published in Gli operaisti, edited by Gigi Roggero, Guido Borio, and Francesca Pozzi (DeriveApprodi, 2005).