Everything passes over the earth.

—José de Alencar, IracemaAh, with me the world will change. I don’t like the world as it is.

—Carolina Maria de Jesus, Diary of Bitita

(Note: The name of each section in this text corresponds to the name in Portuguese of the five stars that compose the Crux or Southern Cross constellation.)

1. Magellan

There is a light hovering over the end of the world, only visible at the very edge of the world. A torturous cross rather than fire or flame, this light hurts more in its distance than its encounter—already impossible without a name for summoning it. This light is conjured within the blindness of the night’s currents, a night that dresses the castaways of Iberian galleons as stars. This light is not a guide, though at the end of the world, it was prone to misuse, whether as astrolabe or compass. This light, no doubt, revealed the poisoned, lost, and putrefying body of the Portuguese captain Ferdinand Magellan, swallowed by a sea of natives on the island of Mactan. Venetian scholar and explorer Antonio Pigafetta, in his account of the captain’s death, for a rare moment changed his tone from that of Magellan’s proto-scientific scrivener performing an autopsy of the world’s first circumnavigation (in which he participated), opting instead for the epic:

Recognizing the captain, so many turned upon him that they knocked his helmet off his head twice, but he always stood firm like a good knight along with some others. We fought thus for more than one hour, refusing to retreat farther; an Indian hurled a bamboo spear into the captain’s face. The latter immediately killed him with his lance, which he left in the Indian’s body. Then, trying to lay hand on sword, he could draw it out only halfway, because he had been wounded in the arm with a bamboo spear. When the natives saw that, they all hurled themselves upon him. One of them wounded him on the left leg with a large terciado, which resembles a scimitar, only being larger; that caused the captain to fall face downward. Immediately they rushed upon him with iron and bamboo spears and with their cutlasses, until they killed our mirror, our light, our comfort, and our true guide.1

Martin Waldseemuller, detail from Map Of The World And Account Of Vespucci’s Voyage, 1507. The Italian cartographer Amerigo Vespucci (1454–1512) demonstrated that the “New World” was a distinct continent (and not part of Asia).

There is a theophagic slant in Pigafetta’s account of the captain’s body being overtaken and dismantled by a sea of Indigenous people; those who the captain failed to convert to communion with Christ now commune through his wounds. Although this is not the end of the voyage— Pigafetta’s account continues up to the return of the ship Vitória to Spain—the death of Captain Magellan marks the endpoint of a truer circumnavigation than the one that only sought routes for the spice trade. It closes the circle of the encounter of the European Christian man with the pagan man of the New World. It unveils Man, no longer hidden behind masks of hospitality, grimaces of complacency, or the lurking prospect of the redemptive encounter, but under the final sign of what governs the flesh of every human—death.

Perhaps, there, in the night, swallowed by the crowd of Indigenous people and imminent death, Magellan encountered the futility of words like “conversion,” “salvation,” and “navigation” which took him to the edge of the world. Despite these solemn and severe words and his own designs, he would remain among those for whom the Iberian nations of Portugal and Spain do not exist. Perhaps there, in the night, he tenderly thought of an escape to where, months ago, he and his crew had encountered “abundant provisions of birds, of potatoes, of a kind of fruit that resembles the pine nut of the pine, but it is extremely sweet and has a distinct flavor”; the land where they carried out “excellent negotiations: for a hook or a knife they would give us five or six chickens; two geese for a comb; for a small mirror or a pair of scissors, we had enough fish for ten people.” A land inhabited by people Pigafetta described as “non-Christian, but neither an idolater.” Here, in the ruptured womb of the modern era, we find one of the first definitions of Brazilians, who “do not worship anything: the natural instinct is their only law.”2

Centuries after having carved laws and incisions under the corpses of the natives, it is by thinking again, like Pigafetta, of the relationship between nature and law that Brazilian poet and philosopher Antonio Cícero understands the development of natural law as a central and unequivocal part of the modern. However, when “natural law consists of purely rational law,” natural law is no longer related to instincts, and shows what is rotten in the realm of modernity.3 Nature is already outside of man—an island without beginning or end, only concerned with the exceptional status of the human and his reason. A certain symmetry is established between the inaccessibility of the self and the inaccessibility of the cosmos, and in this equality the divorce between the two is signed, since there is no clockmaking God nor shaman speaking to trees who can act as interlocutor between them. An unavoidable distance is created between such a subject and object, self and world; modernity is thus inaugurated in what Bruno Latour calls the purification process that delimits “two entirely distinct ontological zones, that of human beings on the one hand; that of nonhumans, on the other.”4

However, for Cícero, modernity before such a split presents a new modality of time. It is the now: “Modernity is nowness, the now itself, the now as the essence of the now, the essence of this instant, which is what we seek.”5 In this conception, the modern is linked to an instant that is always lost, which leads to the question of what constitutes the “essence of the instant”: what initiates the now, and consequently establishes modernity? Cícero responds that “it will necessarily always be this instant whenever I’m able to find myself. I am something that cannot be given without this instant also being given. I am a sufficient condition for this moment to take place … the moment I refer to as this is me. I am also a necessary condition for it to happen.” In other words, Cícero concludes that “modernity is I.”6

Cícero admits that, in the genealogy of the modern, such intertwining between the self and the now, the self as sustaining the instant, has a clear origin in the Cartesian cogito. For Cícero, I think therefore I am inaugurates modernity, because it establishes as necessary and fixed the self that thinks in the now. The only thing that survives in the original Cartesian negation is precisely this I. As the basis of modernity, the cogito can be described as unveiling being as a total negation of the world, which can be condensed as follows: “The world is posited by me as the totality of what I am not in my essence.”7 In other words, I separate myself from the world. The self in this instant, in the now in which it necessarily thinks and finds itself, is apart from the world. In the now, there is nothing but the self and the thinking, the island that moves, year after year, away from the mainland towards itself, to discover its center precisely in the distance it drifts from the origin—the origin that forgets. This distance, the beginning of the split in the now without forgetting or rest, between self and the world, is what, in the end, we can call genuinely modern.

Separated from the world, the subject needs new translations reflecting its new marital status as a divorcé. Natural instinct, the law of nature, is rewritten as logos capable of leading back to a perfect beginning from which the mind would be mimicry and derivation. The subject seeks to reinvent the world that transcends the subject and moves it away from itself. Only the subject and its thought become natural; everything else is contingent. Everything else is idolatry. But the translation is always incomplete. The noble savage sees himself revived in the smoke of industry; the pamphlets of Robespierre and Jacques-Louis David’s Festival of the Supreme Being, at the height of the Terror of the Revolution, asked the French, in one of the most naive demonstrations of nostalgia in the bosom of culture, to beautify their homes with flowers and wreaths in a clumsy attempt to turn the blood of the guillotine into a trail back to a new garden of Eden. If reason becomes natural in such a bricolage, it also becomes more tropical, and the self on its island cannot resist the work of landscaping a lost world.

Centuries after the Festival of the Supreme Being, the thirty-eighth president of Brazil, Jair Messias Bolsonaro, allowed us to say that landscaping the island of the self is no longer possible. It is curious that one of the various adjectives and nicknames for the former army captain was “the enemy of modernity.” Many saw in Bolsonaro and the convulsive theses of his guru—far-right conspiracy theorist, former astrologer, and self-proclaimed philosopher Olavo de Carvalho—an obscurantism of the old regime, a shameless attack on the foundations of modernity using a fascism of old buzzwords. From this perspective, Bolsonaro and what he embodied would be a specter, a memory of the Leviathan that came to haunt the now, to bewitch the thinking self on its floating island of freedom. Bewitched by the spirit of the past that removes it from the now, the thinking self can only throw itself into the sea and condemn its marvelous creation because there is no way back. The now knows no ties to any past. However, it is even more curious that Bolsonaro’s favorite adversary was what his supporters called globalism. In the words of Carvalho:

Globalism is a revolutionary process, there is no denying it. And it is the most vast and ambitious process of all. It encompasses the radical mutation not only of power structures, but of society, education, morals, and even the most intimate reactions of the human soul. It is a complete civilizational project and its demand for power is the highest and most voracious that has ever been seen … an instrument for destroying national sovereignty and building on its ruins an omnipotent universal Leviathan.8

The biblical demon in this fragment is not a fluke or accident. For Carvalho, globalism’s perverse international elite and values attack and bewitch the self and its island with grim fantasies of global warming or historical reparations. Though notions of reality and fantasy seem absurd for someone who declared that Pepsi Cola is made with aborted fetuses, Carvalho never wanted to be recognized as the astrologer of the early 1980s, but as Richmond, Virginia’s philosopher, supported by his numerous students and shelves—of books with complicated titles.

Above all, Olavo de Carvalho wanted to say, as many Brazilians began to say, that he was right (literally “with reason” in Portuguese). What he proposed—and to some extent carried out through Bolsonaro—was not a conservative counterrevolution but a late distorted Jacobinism, which, rather than confronting an I and a now with a lost world, instead manufactured such a lost world by convincing itself that the Terror is actually a restoration. There is no doubt that Bolsonaro did everything to appropriate the basements of the military regime, the tortures of Estado Novo populism, the deepest and darkest wounds of slavery, and an entire authoritarian and bloody legacy concealed by the tropical sun. But in the end, he is the captain who doesn’t know how to shoot, anointed by a digital militia of bots and sustained not by his truculence or virility, but by the passivity with which he surrendered the government to the Brazilian political establishment.

He had to content himself with saying that the constitution was he while he built his Versailles under a fragile jet ski on the decaying coast of São Paulo, where he ordered the burning of the Amazon without really knowing why. He understands, even if in secret, that nothing or no one constitutes anything anymore. Bolsonaro and Carvalho are the ends and the beginning of the split, its eternal return; they “continue to believe in the promises of the sciences, or in those of emancipation,” as true and credulous moderns.9 Still, they manufacture both because they have become owners of a world that they simultaneously invent and flee, accusing it of wanting to absorb them. That is the true meaning of globalism—Bolsonaro and Carvalho fear the world to which they belong, the world that calls to them from the shadows of the trees they burn.

The disaster under Bolsonaro was incalculable, overwhelming—inconceivable precisely as burlesque, as a carnival that came to life and rebelled against the limits of Ash Wednesday, supernaturally, unintentionally. But in this disaster that befell the Western world and its supposedly solid foundations on shipwrecked islands, there is nothing supernatural, ghostly, or unintentional. The self on the island didn’t drown because it was bewitched, since the self could no longer believe in spells. Yet it could enchant itself with its own reflection and sound, as if they belonged to this self’s own world, promising an escape from loneliness, from the bottomless now with no end or beginning, just waiting for annihilation by tide and wind.

Such solitude, supernatural and phantasmagoric, goes back to the moment when schools teach that Brazil, that name without a country, was invented. It goes back to the now in which Portuguese and natives met on the edge of the world to exchange pau brasil (Brazil wood, the country’s first commodity, from a tree that produced the color red in Europe) for mirrors anchored by unfathomable waiting and mutism. And in the twisted mirror image of themselves, the Indigenous people, between the ghosts of captains and scars of desire, in the encounter with themselves, could not hear Marx saying centuries after that there, in their image, was “a definite social relation between men, that assumes, in their eyes, the fantastic form of a relation between things.”10 Things exchanged, stripped, disenchanted, but above all worn out and irreparable—things like everything. While the Portuguese took the red from the tree and the embers that gave it its name, instead of burning and merging the self and the world they limited both to silence in the infinite blindness of fire.

2. Mimosa

It doesn’t take a theologian or an apostle to claim that there are no mimosa plants in the Garden of Eden. God would not allow, between nudity and transparency, the plant that invented mimicry and whose only essence is the betrayal of appearances. In Brazil, it’s not uncommon to see children marveling at how the plant closes with a touch of their finger, hiding itself in the gesture and pantomime in which it appears indecipherable. In their wonder, these children make one think that the mimosa would close even with God’s touch. Not even He could decipher where the illusion begins and ends at the base of creation, that in hiddenness and self-concealment hints at the basis of what one could call autophagy.

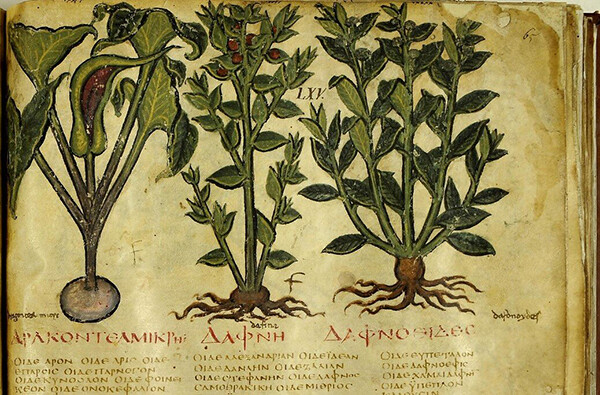

Laurel, or δάφνη (daphne), from the Naples Dioscorides, a late sixth- or early seventh-century manuscript closely related to the Vienna Dioscorides. The author loves this manuscript for all the synonyms it records. Image: Biblioteca Nazionale, Naples.

Mimosas grow under the fences that separate the Positivist Church of Brazil and Benjamin Constant Street in the Glória neighborhood near downtown Rio de Janeiro. Graffiti is everywhere, darkening and protecting one of the many abandoned buildings in downtown Rio. Everything seems to have been turned upside down on the dirty façade of the Positivist Church of Brazil, where one cannot speak of blasphemy only because God was never there. The Positivist Church of Brazil, a civic-religious organization founded on the tenets of Auguste Comte’s positivism, was a temple of Humanity that perished for humanity’s sake. It was men who erased the names of the disciplines of mathematics, astronomy, biology, and sociology from their tiles. It was men who allowed pigeons to make innumerable nests inside until the roof collapsed. But even if the image on its façade of Clotilde de Vaux, who inspired Comte’s Religion of Humanity, can no longer be seen, Comte’s famous motto engraved in stone just below still glows above time and street: Love as a principle, the order as a foundation, and progress as a goal.

Comte’s words always reverberate, even in silence, because they are a reminder of the abbreviation, or rather the mutilation, at the origin of the only verbal marks fluttering on the flag of the Federative Republic of Brazil: order and progress. Brazil’s relationship with Comte’s positivism is indeed one of abbreviation and mutilation, and it remains obscured in the historical footnote that Brazilian historiography has reduced it to. It is forgotten that positivism gave Brazil a mimosa capable of hiding and renewing its dearest split.

In its conception, positivism understands that in astronomy, it is gravity that maintains the balance between celestial bodies, and society needs a similar force to achieve order and progress. If such a force were once made up of the theological and supernatural dogmas that legitimized the social order, they were torn apart by what Comte calls a metaphysical spirit that is nothing but the destructive Enlightenment—and Comte witnessed the Terror of the French Revolution. Such a metaphysical, destructive Enlightenment that “continued to seek new solutions to theological problems, rather than putting aside all impossible pursuits under the realization of their futility” runs contrary to the “true positive spirit which consists in substituting the study of the invariable laws of phenomena for their causes, whether approximate or primary; in a word, studying the how rather than the why.”11

Interior of the Templo da Humanidade, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

For Comte, the “how” of order and human progress is given and sustained only from feeling or social affection, because, as he states eloquently in the epigraph of his works, “We get tired of thinking, and even of acting, but we never get tired of loving.”12 The order of the old regime based on the supernatural, or even the order of Enlightenment reason, cannot be sustained precisely because they cannot sew a genuinely positive social bond. This social bond that Comte calls love can dissolve the notion of individuality and the boundaries between self and other, abolish the separation that threatens order, and definitively integrate everyone into a new and undeniable God with the humble name Humanity. This God of social reality is necessary insofar as it preserves and saves the past, gives meaning to the future, and rescues the self from its island—or at least puts it in perspective amidst Humanity’s vastness.

Comte’s project is, above all, an attempt to live after the death of the Father, after the death of the law and of the world established by a supernatural order of Good dogma—necessary, greater, and above suspicion. Comte wants to avoid fratricidal Terror through the attraction of feeling, affection, and love. But in any psychoanalytic model, the only affection children share is necessarily for the mother. It is not for nothing that Comte invests so much in the feminine, and his entire project of the religion of Humanity derives from his later platonic love for the widow Clotilde de Vaux, who is always dressed as a secular Virgin Mary. He admits that “the movement cannot have strength until women give it their cordial support because they are the best representatives of the fundamental principle of Positivism, the victory of social affections over individual ones.”13 It is as if Comte imagined Humanity as a new transnational and transhistorical mother capable of, through her reciprocal affection, ordering her children in her orbit and remanufacturing time, us, and the world.

In this sense, Brazil is already the end of positivism, even before its elaboration. As Italian-Brazilian writer, psychoanalyst, and dramaturg Contardo Calligaris suggested, Brazil has always been a gigantic mother without paternal interdiction, without her general law or promise, a mother of pure love and affection, yet unable to find children between settler and colonizer, where affection is permanently confused with exploitation. An exploration that has always been gloomy since the colonizer, the first traveler, the exiled conqueror who came to Brazil to discover precisely a maternal body that he could make his own, a lawless body with which he achieves the fortune and pleasure he could not obtain under his father’s tutelage. Yet “the colonizer is sad because, anyway, even if the body between his hands isn’t forbidden and he finds pleasure in it, he’ll always know that it’s not quite the body he wanted. The body he wanted to give an orgasm was the body he left, the interdicted maternal body.”14

Eduardo de Sá, detail featuring a portrait of de Vaux in Altar to Humanity, 1900. Chapel of Humanity, Paris. License: CC BY 2.0.

The colonizer cannot be a father. He cannot be the law because he refused to be a son; he declined the law. The settler, the second traveler, cannot be a father or a law either; he cannot serve as a national identity since he comes precisely to receive a new homeland, an identity, and is not interested in maternal affection because he is looking for a name—a paternal name. For Calligaris, again, “what differentiates the settler from the colonizer seems to be the search for a name. He doesn’t come to give America orgasms, but he comes to America to make a name for himself. He is looking here, in another language, for a new father who interdicts, and suddenly recognizes him.”15 Amidst the lack of a father who can recognize the settler and stop the melancholy and the colonizer’s exploitation, there remains a violated and impotent motherland: Clotilde de Vaux, erased on the facade of the temple of Humanity.

The dichotomy that supposedly founds Brazil is born from the colonizer who seeks to continue exploring, enslaving, and enjoying under a maternal body that he always rejects and the settler who demands from this same body the birth of a father and a law that recognizes him, an impossible birth. An impossibility between the slogans of “change Brazil” and “give me more orgasms, Brazil.” This dichotomy is just a shadow of the dichotomy of the modern itself, an effect of the fact that, for the settler or the colonizer, Brazil does not exist; it is outside them. Brazil is already born from a now where one wants to either enjoy or earn a name, but it can never be more than this now—a moment that can only remain a promise because it is always about to occur. Without past or future, it is extinguished, and must begin in thought and desire outside time.

In such a temporality that is necessarily an interval, an indecision, a now, the nation transits between an object without belonging—on the sidelines like its flora to be explored in the distance—and the symphony of electric saws that prophesy the infinite orgasm and the subject that merely extends the settler: always remodeled, ordered, moralized, transformed into an impossible messianic father who grants recognition and name. It is through the imaginary (but rooted and credulous) distance between these spheres and personas that the colonizer and the settler coexist as a divided and fractured sign of Brazil. The invisible and hybrid zone between them, as in Latour’s analysis, proliferates, multiplies, and survives. The zombified Brazil walks through the centuries wanting to give orgasms and yet simultaneously change.

Continued in “We Too Were Modern, Part II: The Tropical Ghost Is a Cannibal”

Antonio Pigafetta, The First Voyage Around the World, 1519–1522: An Account of Magellan’s Expedition, ed. Theodore J. Cachey (University of Toronto Press, 2007), 57–58.

Pigafetta, The First Voyage, 8.

Antonio Cícero, O Mundo Desde O Fim: Sobre o Conceito De Modernidade (Francisco Alves, 1995), 123. My translation.

Bruno Latour, We Have Never Been Modern, trans. Catherine Porter (Harvard University Press, 1993), 10–11.

Cícero, O Mundo Desde O Fim, 16.

Cícero, O Mundo Desde O Fim, 20.

Cícero, O Mundo Desde O Fim, 43.

Olavo de Carvalho, O mínimo Que você Precisa Saber Para Não Ser Um Idiota (The least you need to know not to be an idiot), ed. Felipe Moura Brasil (Editora Record, 2014), 149–50.

Latour, We Have Never Been Modern, 9.

Karl Marx, Capital, vol. 1, marxists.org →.

Auguste Comte, General View of Positivism (Lulu.com, 2020), 47.

Comte, General View of Positivism, 13.

Comte, General View of Positivism, 187.

Contardo Calligaris, Hello Brasil!: Notas De Um Psicanalista Europeu Viajando Ao Brasil (Escuta, 2000), 18.

Calligaris, Hello Brasil!, 20.