Hurling soup at museum paintings and blocking motorway exits by supergluing one’s hand to the road—these are protest forms that emerged in 2022. And they seem almost soberly realistic, or at least realistically desperate, from the perspective of that common notion that has emerged since Brexit and Trump’s presidency, the Covid pandemic, deadly floods in Pakistan and freak blizzards in North America, and the Russian invasion of Ukraine: that reality is shattered, replaced by a strange, disturbing, brutal, at-times-farcical nightmare lurching towards some gigantic dystopian climax we can all well imagine, pastiched from the many dystopian fictions we’ve consumed. As if to give the whole thing a tingly spiritual twist, the climate activists hurling the soup and supergluing their hands are members of groups called “Extinction Rebellion” and “Last Generation” (Letzte Generation), lending themselves and their cause an unmistakable aura of apocalyptic messianism.

A twelveth-century Venetian mosaic depicts Noah sending a dove to find land. License: Public domain.

If anything is shattered it is not reality but, quite the contrary, the illusion of a reality that “we” lived with for so long. Or rather, this very “we” was part of the illusion. In this privileged “we” bubble, a certain cozy pre-1989 Cold War era hadn’t ended—the cozy part being the place where many were well-off and could build a life in Western urban centers, in default minimum middle-class conditions. This “we” may have continued to think that wars and floods and supply shortages and nutty dictators were something far removed, happening in those “developing” countries. Even when things moved close enough to home—from the Yugoslav Wars of the 1990s, to 9/11, to the so-called “refugee crisis” of 2015—“we” managed to still somehow see these events as irritating divergences from the path towards normalcy. Only ignorance and amnesia could have prevented us from seeing that all parts of the world have been hell at one time or another, in wars and genocides, in floods, droughts, and pandemics; that politics have been awash in fake news and authoritarian propaganda before; or that climate change has been observed for a long time (scientists discovered the greenhouse effect in the nineteenth century and it has only become more clear since the early 1970s).

That said, this longtime ignorance and amnesia have been ruptured by accelerated circumstances, especially in regard to climate change. This is why the protests of Extinction Rebellion and Letzte Generation are completely justified and sound in terms of their general rationale—that in the face of climate-related tipping points and domino effects that could destroy the way of life of a large part of humanity, measures to radically reduce carbon emissions have to be taken as decisively and as soon as possible. But in the way these protests are enacted, they also feel partly misguided—whom or what do they actually disrupt in order to exert pressure on whom? While they do feel justifiably desperate, that desperation—present in the theatricality and possible self-harm of the actions, but also in the statements made by individual members—links directly to that awkward sense of messianism. This aspect of apocalyptic messianism has reminded me of two other phenomena, one current and one historical.

The first concerns the curious phenomenon of geek billionaire preppers. Media theorist Douglas Rushkoff’s 2022 book Survival of the Richest starts with a first-hand experience that is so unbelievable that it must be true (also because cyberpunk veteran Rushkoff is a generally reliable source). After five tech-investing entrepreneurs summon him to a remote desert luxury spa and pay him a handsome fee, he learns that they wish to consult him not regarding predictions about, or ways to prevent, the coming societal collapse—what they call “The Event”—but how to effectively escape it, as in how and where to build the best and most effective doomsday bunkers. Rushkoff, stunned, provides an initial explanation: these guys are hellbent on making as much money as fast as they can so that they will have an escape plan for a disaster caused exactly by their very own money-making. “It’s as if they want to build a car that goes fast enough to escape from its own exhaust,” he writes.1 The ultimate expression of this fantasy was the 2021 circle jerk of Jeff Bezos, Elon Musk, and Richard Branson shooting themselves and their rockets into space, at the height of a global pandemic.

Climate activists from groups like Extinction Rebellion and Letzte Generation do not seem to see these tech billionaires as their nemeses. Most of them don’t seem to even properly consider them as targets in the first place (maybe the possibility is psychologically repressed because it would bring up questions of class and wealth?). Perhaps their actions—which have generated a lot of media coverage—should focus not so much on convincing the general public that climate catastrophe is looming by addressing random motorists with calls for cheap public transportation, but rather on directly confronting the rich and powerful with the impossibility of escaping the effects of their deeds—which is what many other activists have aggressively and sometimes successfully done in recent years, from Nan Goldin confronting the Sackler family to Oxfam’s recent detailed report on wealth inequality, titled, like Rushkoff’s book, “Survival of the Richest.”2 And there have been, more recently, in November 2022, a number of actions where some activists have actually come around to confronting the rich—namely the users of private jets at Amsterdam’s Schiphol Airport and at London Luton Airport.3 But so far, this has not developed into a continuous pattern.

The anti-nuclear power movement’s Smiling Sun logo says: “Nuclear Power? No Thanks.”

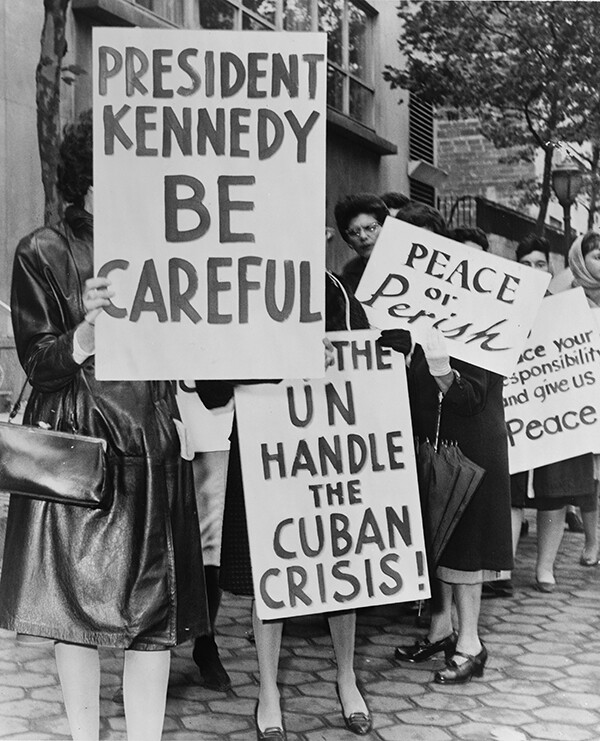

The second, historical phenomenon I was reminded of is strictly speaking not historical because it is not complete. It leads back to a time, at the height of the Cold War in the late 1950s and early 1960s, when doomsday scenarios didn’t feel so much like the result of a messy cluster of causes and catastrophes but of a stalemate between two central parties, each with one finger on the red button: the threat of global nuclear war. In many of his essays from that time, Günther Anders—the Jewish-German philosopher who went into exile in Paris in 1933 with his then-wife Hannah Arendt, then to the US, before moving to Austria in 1950 and joining the postwar antinuclear movement—wrote of a “preempted future as past,” and of humankind’s need to overcome its “blindness to apocalypse.” In his short story “Die beweinte Zukunft” (The Future Mourned), written in 1961, Anders adapts the biblical tale of Noah’s Ark. In Anders’s version, Noah initially wants to build a fleet of a hundred arks, but frustratedly tears up the construction plans as he realizes that he has failed to convince anyone that the flood is actually coming. Boldly, he decides to put on a sackcloth and publicly demonstrate that he is mourning—considered a grave sacrilege if no one close to him has actually died. As a crowd gathers around him, questioning him about his loss, he eventually tells them that he is mourning all of their future deaths, as no one will survive the flood to mourn them. This time, his public theatrical act does have an effect on at least some of his listeners, and as he goes back home, some of them join him to build at least one ark.

Written a year before the Cuban Missile Crisis (the confrontation that arguably brought the world closest to nuclear war), Anders’s piece was not only biblical in its reference but also in its evocation of the necessity to prophesize, and to attract attention in order to convince. Its main point was to establish the idea that nuclear war would indeed mean the total annihilation of humanity, and that ignoring this threat amounted to what he called Apokalypseblindheit—blindness to apocalypse. With films like Adam McKay’s Don’t Look Up (2021), this notion that people refuse to look in the direction of what is on the horizon has become the stuff of general public consumption.

Women Strike for Peace during the Cuban Missile Crisis. License: Public domain.

However, thinking of the billionaire preppers, today’s issue is not so much that there is a “blindness” to apocalypse—even the richest are preparing for this eventuality—but rather ethical and political resistance to thinking of any possibility of working towards global change that would prevent total annihilation in the first place, or at least downgrade it to a severe catastrophe. A subset of new climate activists, understandably frustrated by the general public’s unresponsiveness to predictions of destruction, seems to have resorted thus far to mild shock tactics. These do not appear to be geared towards prompting concerted action, but rather towards prompting media attention and controversy—which has resulted mainly in collective headshaking, a sentiment that is difficult to describe as the first step towards political mobilization. What it does do is distract from the grassroots, often long-term struggles of those who are actually mobilized already (from Fridays for Future, to activists focusing on climate change litigation, to Indigenous groups fighting corporate and political exploitation in the Amazon region).4

These phenomena boil down to what could provisionally be called the Noah complex. Like Noah, the acting subject seeks to resist the coming doom; but like Noah, the subject’s question is whether they feel obligated more to the public/the collective, or to a higher purpose. In what way is this subject, in the end, thus obligated only to itself? Before attempting to answer these bigger-picture questions, it’s necessary to have a closer look at some of the details.

A regular event on a regular Monday morning in Berlin, January 2023: the city autobahn exit leading towards the district of Wedding is blocked because climate activists of Letzte Generation have superglued themselves to the road surface. Less than half an hour later, Berlin’s traffic information center tweets that the blockade has been resolved and the exit can be used again. The event—much like hundreds of similar events that have taken place recently in Berlin and other parts of Germany and Austria—largely follows the example established by the group Insulate Britain (the curious name referring to their single demand for all UK social housing to be heating-insulated by 2025, and all homes by 2030). The choreography of Insulate Britain, which started actions on London’s M25 motorway in September 2021, has become the routine choreography of the protestors of Letzte Generation as well: first, they stand in front of cars, holding up horizontal orange banners with the group’s logo—a black heart in a red circle—and slogans such as “What if the government doesn’t have a handle on this” or “Last generation before the tipping points.” Drivers shout insults at them, or sometimes drag them from the street, while the protestors remain passively nonviolent and return to their place. Then the protestors themselves call the police, letting them know they are enacting a blockade; before the police arrive, the protesters sit down and superglue one hand to the ground; the police get there and use vegetable oil to dissolve the glue. Usually the activists receive a fine, and in some cases are detained, before they return to participate in the next protest.

“Climate Activists Occupy Greenpeace UK Headquarters—Wait, That Can’t Be Right,” reads a headline from October 2018, when in fact it was right: members of a new group called Extinction Rebellion had started a sit-in at the London office of Greenpeace, the veteran environmental organization founded in 1971, accusing them of not being radical enough in the face of accelerating global warming.5 Apart from crackpot climate-change deniers, no one would really deny that these activists are correct in their basic assumptions about climate collapse. However, there is a whole spectrum of assessment regarding the ethical justification of their forms of civil disobedience, and how politically and strategically productive—or counterproductive—they are.

The word Klimaterroristen (“climate terrorists”) was rightly declared the Unwort (misnomer) of 2022 by a jury at Germany’s Marburg University, which gives the award annually to a defamatory or euphemistic term used in public debates. When the number of traffic blockades increased in spring 2022, right-wing populists in the German parliament and press were quick to compare Letzte Generation to the Red Army Faction—which meant equating them with terrorists who, from the 1970s to the early 1990s, committed thirty-three murders as well as numerous hostage-takings, bank robberies, and bomb attacks. Obviously, this extreme exaggeration is aimed at generating cheap populist outrage on behalf of annoyed motorists.

Regardless of what Letzte Generation activists are accused of, so far all of their actions have in fact abided strictly by the definition of civil disobedience neatly formulated by John Rawls in 1971: “a public, nonviolent, conscientious yet political act contrary to law usually done with the aim of bringing about a change in the law or policies of the government.”6 In fact it is impressive to see, in footage available on social media, the restraint and minimal resistance with which the demonstrators have so far reacted to assaulting passers-by trying to drag them away, or to aggressive drivers who have tried to push them aside by driving slowly into them (thankfully, nothing worse than this has happened yet, but it remains to be seen whether drivers might become more aggressive and violent).

Meanwhile, the people who are generally sympathetic with the demonstrators’ motivations are divided over whether the precise demands, methods, and the chosen context and target of the protests are the right ones. Those fully in support seem to assume that any kind of disruption of everyday life is good as long as it generates media attention for the cause—even if the protests mainly affect suburban motorists, or works of art in public museums.

I belong to the group that disagrees. My impulse is to say: fair enough, I respect nonviolent civil disobedience in the face of aggression, and the willingness to risk your health and well-being—but why these specific aims, and in these places, against these specific people? For the actual political demands voiced by Letzte Generation are surprisingly pedestrian. The demands seem as easy to remember as they are comparatively easy to achieve: for example, a hundred-kilometer speed limit on German autobahns. This is obviously a good idea, since the one thing that has kept this limit from finally being introduced (Germany being the only country in Europe with no universal motorway speed limit) is the liberal democrats of the Free Democratic Party (FDP), who are part of the governing coalition. In the midst of coalition negotiations in late 2021, FDP leader Christian Lindner was famously in regular phone contact with the head of Porsche (an incident later described as #Porschegate), and the party has unashamedly acted as the political arm of the German car industry. It seems absurd that the protests do not direct their nonviolent disruption against the FDP and that very car industry, but rather against the Green Party (which is seen as responsible for climate-related issues) and lower-middle-class drivers.

Letzte Generation’s second major demand is for the permanent reestablishment of the “nine-euro ticket,” a monthly transit ticket that was temporarily issued in Germany over the summer of 2022 in the wake of the energy crisis caused by the Russian war against Ukraine. The ticket was valid for local transport and regional rail all across the country. This demand seems rather maximalist in the face of a plan announced by the federal and state governments of Germany to permanently establish a forty-nine-euro ticket starting in May 2023. This would allow everyone in a nation of eighty million to travel around the country for what still seems like a modest price, amounting to a pretty radical change in transport policy. This is not to deny that forty euros, for low-income families, is still a substantial difference, but will this demand be the decisive wake-up call that prevents climate catastrophe? Rhetorical question, obviously.

One gets the impression that the members of Letzte Generation are, again, mainly disappointed in the co-governing Green Party and want to shame them for making compromises, by whatever means. It’s anyone’s right to take that position of course, but especially combined with theatrical acts of civil disobedience, it seems at best naive in terms of addressing the overall global issue. Is the best way to effect real change to shame those who have taken hard-won baby steps toward that change? One curious thing about Letzte Generation’s public statements is that, while they clearly want to pressure the Green Party, they keep addressing chancellor Olaf Scholz and “our government.” The strategy seems to be to keep the message simple, but it is actually counterproductive if the intention is to activate civil society, which would require addressing the role of international capitalism in all of this. It sounds a bit pubescent, if not oedipal: our parents are the ones to blame for all the things that have gone wrong. While many elsewhere, led by Greta Thunberg–like rhetoric, address the powerful in a broader sense, Letzte Generation thus far have mostly confined themselves to addressing their specific national government and its leader.

What’s more, the “our” of Letzte Generation, the “we” that makes these demands, is strikingly and almost universally white, nonmigrant, and middle class. (Related groups in the UK, Italy, and Spain seem to fare a bit better in this regard.) This is disturbing since the first lesson in any kind of contemporary progressive politics is that one should listen to, and intricately collaborate with, those who are most impacted by the issue at hand, in this case climate-damaging, accelerating, extractive, capitalist exploitation, which impacts both the working-class migrants down the street doing shitty service jobs, and communities in other parts of the world that are being hit hardest by climate change. Neither seem to be included in Letzte Generation’s membership or political orientation.

Wealthy, isolated members of the (usually) second-to-last generation are not the focus of these activists either. Unless they are donors: the US-based grantmaking foundation Climate Emergency Fund, like other groups in other countries, substantially co-funds the activities and livelihoods of Letzte Generation activists, via an intermediary German foundation.7 Aileen Getty, heir of a fossil-fuel fortune, proudly and publicly identifies herself as a major donor to the Climate Emergency Fund. She published an opinion piece in the Guardian in October 2022 with the headline “I Fund Climate Activism—and I Applaud the Van Gogh Protest.” She writes: “My support of climate activism is a values statement that disruptive activism is the fastest route to transformative change.”8 She does not go on to explain the causal chain from “value statement” to disruption to rapid global transformation. Nor does she explain how the tomato-soup-on-Sunflowers action, while purposefully targeting a painting protected by glass so that no actual damage was inflicted, will have such an amazing effect. One gets the impression that for rich donors, the main gratification is relief from guilt (a contemporary form of buying indulgences from the medieval church to absolve one’s sins). But they also enjoy the sugar high of proxy performative heroism, which is especially sweet since it demands nothing of them except a bit of their money, and it supports their fantasy that “disruption,” as in the business lingo they speak, is the magic spell—a spell that wards off grassroots collectivity, democratic processes, unions, and community alliances.

Looking at the long list of art-related protest actions, they focus largely on famous works in big public museums such as the National Gallery in London, the Gemäldegalerie in Berlin, and the Vatican Museums in Rome. There are, as far as I can tell, only two exceptions, where the targets were artworks in private museums owned by billionaires. On October 23, 2022, two activists threw potato soup at Claude Monet’s Les Meules (Grainstacks, 1890) in Potsdam’s Museum Barberini; the museum, along with the multimillion-dollar painting, are owned by the software entrepreneur Hasso Plattner. On November 18, 2022 in Paris, two activists from the French group Dernière Rénovation poured orange paint over Charles Ray’s Horse and Rider (2014), a life-sized stainless-steel equestrian sculpture displayed outdoors, in front of the entrance to the Bourse de Commerce, the museum housing the private collection of François Pinault, whose net worth is estimated at close to $40 billion. Curiously, in both cases, the activists mentioned the general urgency of acting on climate change—but said nothing about the superrich owners of these places and artworks, nor about how the accumulation of their wealth contributed to climate change, making them partly responsible for it.9

xPoint is an abandoned military facility turned survivalist community at the base of the Black Hills in Fall River County, South Dakota. Photo: Vivos.

My point is not to say that the billionaire owners of tech and luxury companies should be the only ones held responsible for climate change. But why have they been exempt from the types of protest actions described above? What have they done to deserve a pass? My guess is that it’s a result not of cowardice (let’s not piss off these powerful people, who could be potential donors), but naivety: these actions focus on theatrical “disruption” to draw attention to an issue or demand, while not even attempting any serious societal or economic analysis (Marxist or otherwise) to address, for example, the dramatic under-taxing of the uber-rich.

Or maybe it’s not naivety but a form of freaked-out desperation—in the sense that addressing the intricate connection between fossil industries and the greenwashed “cleanliness” of digital capitalism, or between both and our corrupt political leaders, is simply too complicated to unravel, too complicated to convey to a wider public, and therefore futile to discuss. The purpose of these actions is then to testify, on record, to yourself and to others in a dystopian future, that you at least tried to warn people and raise awareness. Told you so. At least I tried.

Luckily, the groups that have thus far focused mostly on “disruptive” actions are realizing the limitations of this tactic. In a New Year’s Eve announcement entitled “We Quit,” Extinction Rebellion UK stated that in 2023 they will “temporarily shift away from public disruption” and instead “prioritise attendance over arrest and relationships over roadblocks”—in other words, switch to classic mass mobilization and street demonstrations.10 One could interpret this as a mere PR move, but it seems to be more than that: a justified acknowledgement that one doesn’t have to reinvent the wheel of protest to effect change. Maybe relationships (of the robust and sustainable political kind) are more important than roadblocks.

Even if I regard the actions of Letzte Generation as naive and misguided, I cannot ignore the determination of these activists and their willingness to make sacrifices, while billionaires either ignore the impacts of climate change around the world, or pay it lip service by donating a few dollars. Even their prepping plans seem stupid—as Rushkoff reminds them, in a dystopian collapse scenario their remote luxury hideouts would eventually fall into the hands of their own highly trained guards, because you can’t enforce or buy loyalty in an apocalyptic situation. Disrupting their own disruptive thinking, their own privileged, not-so splendid isolation—what Rushkoff calls “the Mindset,” a tech-fetishizing, winners-and-losers worldview yearning for an endgame—is the one thing they’re unable to countenance.

There is a film clip of Günther Anders reading from his short story “The Future Mourned” in 1987.11 In his introductory remarks he says that the story would never have been written if he hadn’t been invited by a certain Gudrun Ensslin to contribute to a book called Against Death: Voices of German Writers against the Atom Bomb, published in 1964.12 Ensslin, who was the coeditor of the book, later became one of the leaders of the Red Army Faction and died in Stammheim prison in 1977. But in the early 1960s she was still a top student in Tübingen, the daughter of a vicar. This is not to say that right-wing pundits who denounce the new activists as “climate terrorists” are right (that would be an absurd historical parallel). It is rather to note that any political determination in the face of looming catastrophe leads to forked paths; in Ensslin’s case, her militancy was largely determined by the police murder of Benno Ohnesorg, a student, during a 1967 demonstration in Berlin. But the militancy that she, as part of the Red Army Faction, practiced and advocated was as isolated as it could be from what it rhetorically referred to—the guerilla wars of national liberation in South America, Africa, and Asia. “Six against sixty million,” as German writer Heinrich Böll once put it. For today’s new activists, the lesson of this moral and political failure is to take the path of nonviolent civil resistance.

In 1967, Benno Ohnesorg was shot outside the Berlin Opera during a protest over the state visit of Mohammad Reza Pahlavi. License: Public domain.

Anders’s story—a Biblical allegory about nuclear war—can also be read as an allegory about climate change, even if the catastrophe in this case is not a single event but a messy cluster of separate-seeming but intricately connected biospheric disturbances. In Anders’s story, Noah demonstrates the importance of collective action and collective mourning, rather than solitary escape, in the face of apocalyptic destruction. That is what I call the Noah complex: the yearning to overcome the split between fantasies of a clean escape and the messy building of social coalitions. We simply can’t afford to wait for the awakening of a universal sense of human collectivity. But we also can’t let these isolated escape fantasies go unchecked. The messy, radical, pragmatic business of transforming our economic and social system has to start now.

Douglas Rushkoff, Survival of the Richest: Escape Fantasies of the Tech Billionaires (Norton, 2022), 10.

See →.

Denise Chow and Evan Bush, “Climate Activists in at Least 13 Countries Protest Private Jets,” NBC News, November 10, 2022 →.

Michael Molitch-Hou, “Climate Activists Occupy Greenpeace UK Headquarters—Wait, That Can’t Be Right,” Common Dreams, October 19, 2018 →.

John Rawls, A Theory of Justice (Harvard University Press, 1971), 364.

See → (in German).

See →.

See →.

See →.

Gegen den Tod: Stimmen deutscher Schriftsteller gegen die Atombombe, ed. Gudrun Ensslin and Bernward Vesper (Tübingen: Studio Neue Literatur, 1964). Reissued by Edition Cordeliers, 1981.