The following is an edited excerpt from Jussi Parikka’s forthcoming book, Operational Images: From the Visual to the Invisual (University of Minnesota Press, summer 2023). The book takes up Harun Farocki’s well-known concept of “operational images” and, moving across art, design, architecture, and visual cultures, offers a guide to understanding contemporary practices of imaging and data, from visual arts to the invisual operations of AI and machine vision.

***

Capturing Light

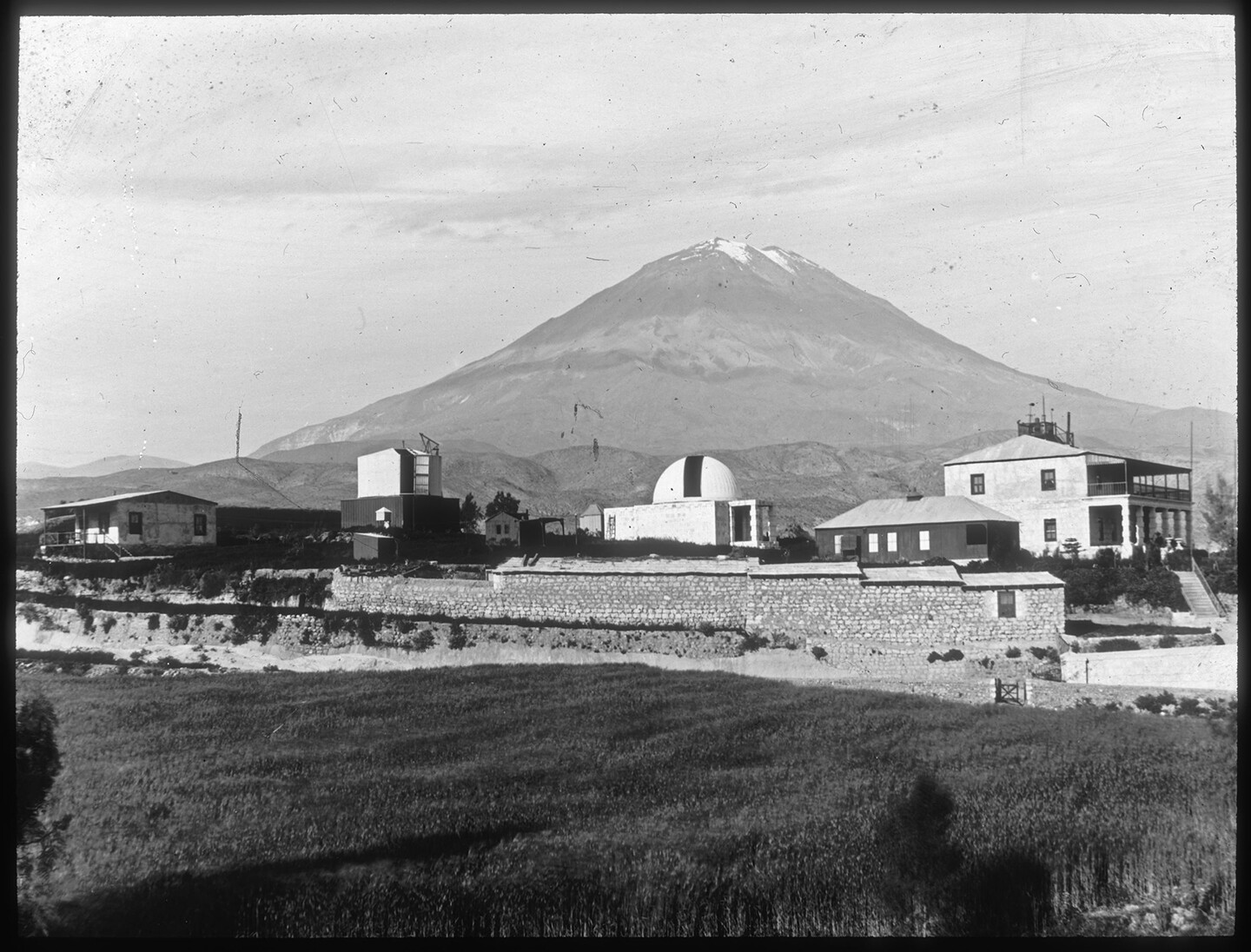

Around 1889, Harvard College expanded its influence far outside Cambridge, Massachusetts. Having joined the College Observatory (first as a student, later as a professor of astronomy), Solon Irving Bailey was sent much farther south, to Arequipa in Peru, to establish a new field station. This operation was to switch hemispheres and find a spot elevated enough for ideal observation of the light traveling from distant celestial objects. Astronomic photography had a long history already by the 1890s, but this need for a new observatory emphasized the additional demand for what we would now call scientific infrastructure. After New Year’s Day in 1889, a boat trip from San Francisco took Bailey and his family to Arequipa, “attracted by reports of the clear sky and slight rainfall on the high plateau of Peru, where also the whole southern sky is visible.”1 While the rhetorical emphasis on a clean, crisp observation place puts all of the weather conditions easily outside of history and into the physical sphere, important for astronomy as a science of the observation of laws (out there) and not things (here), during the difficult trip to find the perfect spot Bailey observed and (in passing) noted the colonial legacy of the region: “I should place the population of the valley near Chosica in the days of the Incas at six thousand. Today there are perhaps five hundred. This well illustrates how Peru has changed since she fell into the hands of the Spanish conquerors.”2 Such awareness in his thoughts and diary did not, however, prevent the expedition from (re)naming the place they came to in a softer but still imperial manner: Mount Harvard. The eponymous name was entirely in tune with the aims of Edward Pickering, the long-standing and renowned director of the Harvard College Observatory, to establish posts in the north and the south, “so the entire sky would be available for Harvard’s research.”3

Besides a number of adventurous anecdotes from that trip, the relation with a media technological context is especially interesting. Two themes concerning light intersected during the years Bailey spent in Peru, both of which were essential to the scientific work, while producing an aesthetic quality to the geographical placement. The sunlit high-altitude plains—causing occasional mountain sickness for the party looking for a suitable observation spot—provided ideal landscapes, while the photometric (measurement of the brightness of light) and photographic techniques provided technologies for the capture of slowly shifting objects in the night sky. Not that such exact spots of observation were known in advance; some of Bailey’s memoirs from the trip read as a persistent search for those spots where measurements can be made, leading him to echo earlier advice about the exploratory spirit: “Of the clearness and steadiness of the atmosphere in these different places, there is no certain knowledge, and your only way is to investigate it for yourselves.”4 The investigation aimed to take pictures to send back to the college in Cambridge. Besides telescopes, the comparative analysis of photographic evidence became a key technique that needed a reliable data supply. It was, in some ways, a case of what Michelle Henning has called “the unfettered image”: fixed as image, but migratory and journeying as an object.5 Here, what migrated were the comparative observations of the vast space outside the planetary sphere.

Arequipa station of Harvard university, Peru. License: Public domain.

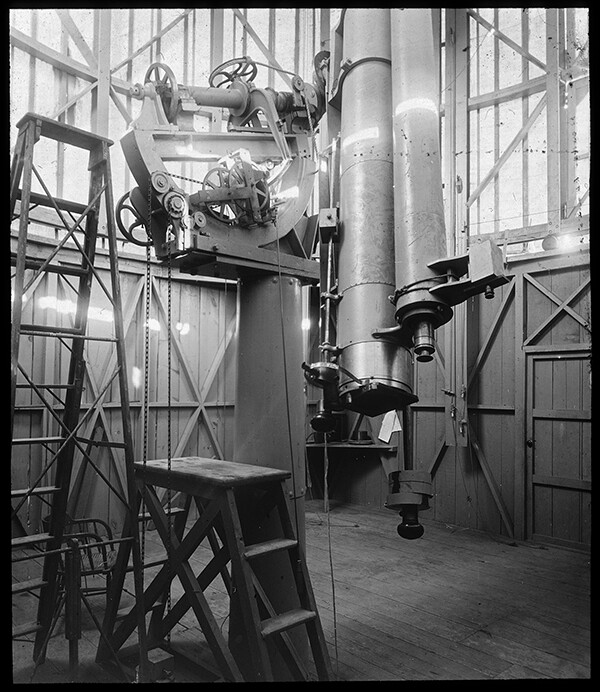

As per the Harvard Observatory’s aim, to be able to observe the night sky from both the Northern and Southern Hemispheres gave a particular advantage to astronomers. Moreover, with the help of the photographic media, Southern data was relatively easily transported back to Cambridge for comparative, computational analysis. In Pickering’s words, “For many purposes the photographs take the place of the stars themselves, and discoveries are verified and errors corrected by daylight with a magnifying glass instead of at night with a telescope.”6

The photographs from Bailey’s field station were sent north. This part of the logistical story has become more well-known in recent years, particularly the (female) computer pioneers of data analysis and astronomy, including Annie Jump Cannon and her work on star classifications7 and Henrietta Swan Leavitt, among others. Leavitt, later awarded the title “Curator of Astronomical Photographs” (held earlier by Williamina Fleming), left lasting contributions to the field (even if here the focus is only on parts that relate to the media technological operations that serve as infrastructure and instruments of astronomy as a science). Leavitt’s research impacted astronomy by demonstrating important traits about the periodicity of brightness, an essential element in measuring distances across the vastness of outer space. In addition, the Peruvian night sky had been photographed and recorded on glass plates that Leavitt stacked on top of each other for comparative data analysis and to produce insights into the shifts of moving stars, which in our case illuminates a key theme: early in its first official century, photography was already a measurement device that not only took pictures of people and things but offered a way to analyze the world, including the extraterrestrial.

As such, the point about technical images and measurement has already been articulated; for example, Kelley Wilder gives a good overview of some of the practices of astronomical imaging before and after the Harvard period in question and opens up important points more generally, too. Besides photographs where “the ability to measure appears to be a useful but unintended byproduct,”8 there were various intentional practices, mostly scientific, where this cultural technique was central. In astronomy, this included the Venus transit plates of 1874 and institutionalized work such as Carte de Ciel of the 1880s, “one of the most influential photographic observation projects in astronomy.”9 Beyond astronomy, Raman spectroscopy and photogrammetry were “methods that bent photographic observation to mathematization,” with surveying as a technique that was, as Wilder outlines, “heavily dependent on the idea of measurable photographs.”10 Here, the commentary on measurement serves to illuminate the expanded scope of operational images to be discussed below.

Harvard College Observatory, Arequipa, Peru. Source: Harvard Library.

In aptly contrasting ways, the title of Leavitt’s 1908 paper, “1777 Variables in the Magellanic Clouds,” rings poetic, while the opening sentence nails the argument about images as infrastructures of analysis and comparison in a pithy, informative fashion: “In the spring of 1904, a comparison of two photographs of the Small Magellanic Cloud, taken with the 24-inch Bruce Telescope, led to the discovery of a number of faint variable stars.”11 Where Bailey had engaged with the landscapes of Peru, its altitudes and terrains, the shipment to Cambridge provided the other side of this landscape; in Leavitt’s reading, the Magellanic clouds—or, more precisely, their photographic recording—provided a dynamic, periodic landscape of light to be interpreted. Leavitt writes about light that she has been observing on those records:

The variables appear to fall into three or four distinct groups. The majority of the light curves have a striking resemblance, in form, to those of cluster variables. As a rule, they are faint during the greater part of the time, the maxima being very brief, while the increase of light usually does not occupy more than one-sight to one-tenth of the entire period.12

Surely, Leavitt and others would have cursed Tesla’s Spacelink satellite program that hinders the subtle balance and periodicity of the sky with its mass flooding of orbit. However, around the 1890s and 1900s, the night sky was still stable and observable through the gridded transparency of the glass plates that opened up possibilities of comparative analysis.

Large Magellanic Cloud taken on December 18, 1900 from Arequipa, Peru.

While the sky had been pictured, read, observed, interpreted, and calculated for millennia, as John Durham Peters argues in his media theoretical insight into astronomical star-gazing, the scientific analysis of movement and light became particularly interesting toward the fin de siècle.13 The employment of both media of visual technologies (photography and spectral analysis) and the possibilities to harness the planet’s spherical shape—Northern and Southern Hemispheres into a binocular view of sorts—as part of the astronomic observation unit from Peru to Massachusetts provided the backbone for broader infrastructures of knowledge. The intersections of media and the sciences (in this case, astronomy) have impacted the transformation of photography as it became “digital” and was integrated into data analysis and planetary infrastructure. Even the shape of the planet measured in geodesic triangulation can be considered part of the story of the extended planetary image.

As already mentioned, this link to scientific uses of photography, including in astronomy, should not be particularly surprising considering that perhaps the most famous words in the early history of photography (or, more specifically, the daguerreotype) were uttered by an astronomer, François Arago, in an 1839 address. This talk was given to convince the French Academies of Art and Science of the benefits of the new technique, which was why the talk aimed to make sure it was seen as a scientific one and therefore included specific attention paid to the various uses of measurement: beyond people or things, landscapes or scenes, this was a medium to measure photometrically the brightness of transmitted light and thus also provide an insight into what lies beyond this particular planet and how that can be easily recorded on a plate. Thus, the instrument became a central part of an experimental apparatus that unfolded a whole visualization process in developing an image.14

As pointed out by Wilder, the nineteenth-century history of photography was filled with astronomical works and interests: William de Wivelselie Abney, E. E. Barnard, William Crookes, L. J. M. Daguerre, John Draper, Paul and Prosper Henry, Jules Janssen, Hermann Krone, Adolphe Neyt, Warren de la Rue, Lewis Morris Rutherford, Hermann Wilhelm Vogel, and John Adams Whipple are among a list of practitioners relevant to both sides of this technical expertise. Wilder argues that “much of their work revolved around adapting emulsions and photographic instruments to astronomical observation, and they produced everything from spectra of starlight, to photometric readings, to iconic images of the heavens.”15 While much of the focus in earlier research has been on the apparatuses and their relation to both histories of technology and, in some cases, scientific discourses of validity and reliability,16 adding an emphasis on Leavitt opens a particularly interesting avenue of consideration not only for the history of photography but also for the theoretical topic at hand, operational images.

The Operational Image

Coined by the renowned German filmmaker, artist, and writer Harun Farocki (1944–2014), the term “operational images” appeared in the early 2000s in his video installation trilogy Eye/Machine I-III (2001–3), which investigates autonomous weapon systems, machine vision in industrial and other applications, and the broader move from representations to the primacy of operations.17 Farocki’s film installation series presents this shift as a particular kind of image that emerges in those institutional practices, although it also articulates the shift through the various histories and spaces that condition both the emergence of such images and their industrial base: these include military test facilities, archives, laboratories, and factories.

This institutional line of references is common in many of Farocki’s films that investigate how contemporary images are intimately tied with modern forms of industrial production, departing from a history of images focused only on visual culture to embrace histories of chemistry, violence, labor, exploitation, and data. Already in Images of the World and the Inscription of War (1989), Farocki mapped a similar terrain of investigation, exploring how to read landscapes, aerial imagery, targeting systems, and also other forms of modeling, simulation, and aesthetic techniques as they operate in the world in the fundamentally material sense.

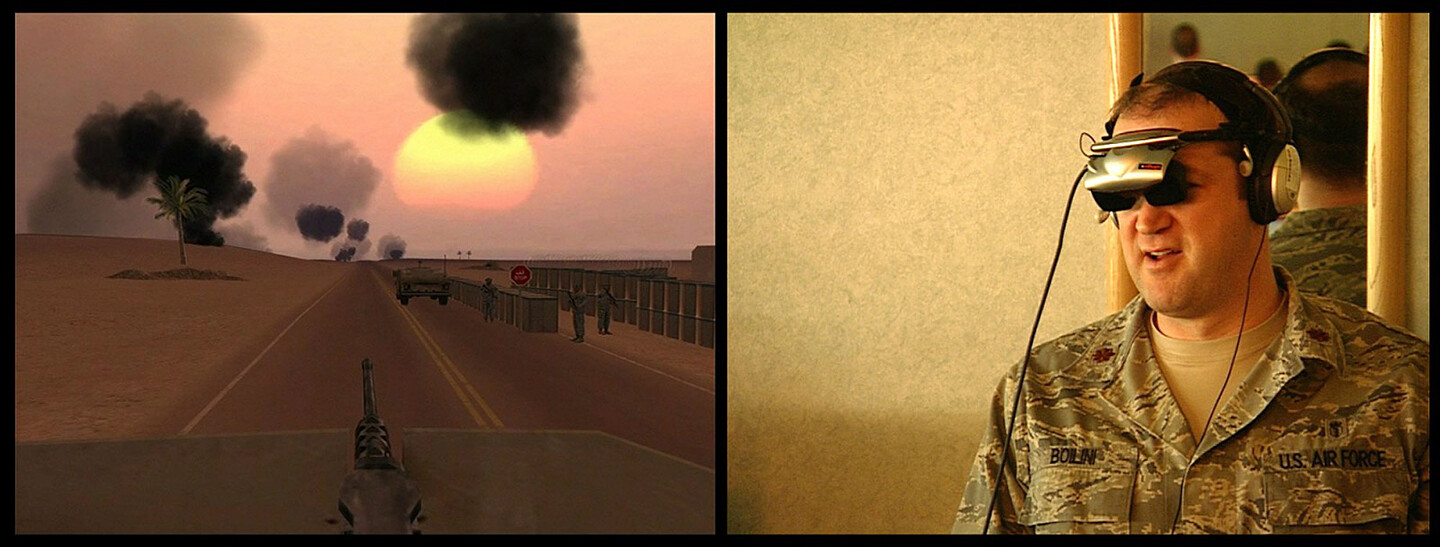

Harun Farocki, Eye/Machine I-III, 2001–2003.

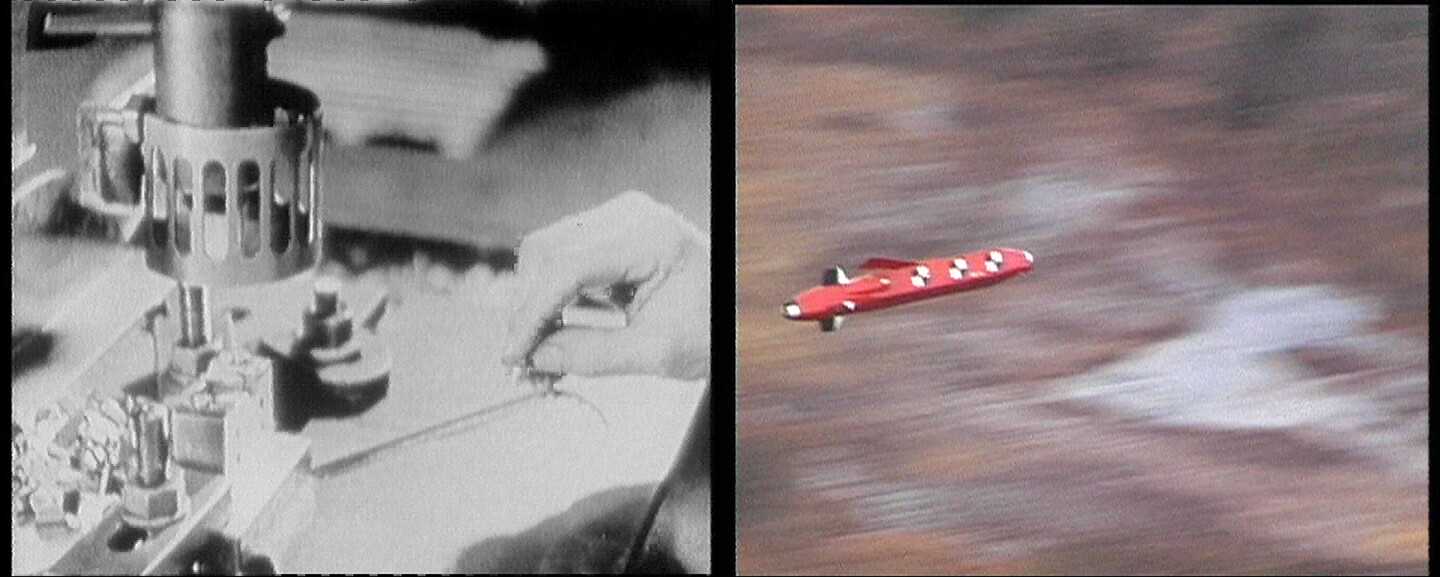

Farocki’s work with images about images sets a scene and opens up an artistic, epistemic, and research-focused agenda. Eye/Machine III (2003) is one such example, where operational images are articulated across a set of cases: factory scenes of data and measurement for infrared aircraft detection systems, the laser scanning of built structures, and the engineering of robotic navigation systems that sense the space around them. Images produced in these situations are drawn from machine-vision systems of perception, embodied and embedded in autonomous or remote systems, working through an artificial environmental relation where the image is a crucial part of movement and guidance.18 Operational images are, in Farocki’s words, “pictures that are part of an operation,” implying the primacy of action and function instead of a picture to be seen and interpreted for meaning.19 Perception is tightly coupled with action, immediate or delayed. This coupling systematically operationalizes terrains and targets. Hence guidance systems, movement, tracking, measurement, and precision are some of the contexts that take precedence in such images that are often, in terms of visual history, “inconsequential,” as Farocki bluntly puts it.20 The notion of the “operational image” is also a condensation of an aesthetic program that relates to what images are seen, which ones are archived, and which ones of the multitude of images are merely used and erased:

Images that appear so inconsequential that they are not stored—the tapes are erased and are used again. Generally the images are stored and archived only in exceptional cases, but exceptional cases one is sure to encounter. Such images challenge the artist who is interested in a meaning that is not authorial and intentional, an artist interested in a sort of beauty that is not calculated. The US military command has surpassed us all in the art of showing something that comes close to the “unconscious visible.”21

While military contexts of machine vision have taken up most of the commentary and attention when it comes to Farocki’s notion and its articulation in moving images and photography, it is clear that the breadth of examples tells a larger story than one merely about genealogies of military vision systems. This is not to dismiss such a key trait. Farocki’s examples—from a 1942 instructional film showing the operations of a V-1 guided missile, to the 1990s military systems that became a key topic for art and media theory from Jean Baudrillard to Paul Virilio—are persistently apt in the context of contemporary drone warfare and in the media archaeology of military vision. Even Farocki himself reads “the US military command” as part of a new aesthetic operationality of visibility.

Furthermore, operational images concern not only perception and sensing turned into images but also operations. The history of the centrality of “operations” can be traced to the field of operational (or operations) research (OR) as developed by the US and British militaries starting in the 1930s but especially during the war years of the 1940s: quantifiable analysis of military operations for purposes of optimization. The field then developed into the Cold War’s “speculative fabrications of systems analysis,” such as those produced by the RAND corporation in the United States.22 These are institutional-level “machine learning systems” that aim to formalize, train, and model based on available quantitative data. Learning itself becomes a formalized operation. For OR pioneers and controversial practitioners such as Herman Kahn, the successes of operations research in World War II proved the greater effectiveness of mathematics over time-honored tactics. Systems analysis was unquestionably superior, in his view, despite the common belief that “experience” has been a better guide than “theory” in this kind of work.23

Of course, an opposition of theory vs. experience was a bit of a simplification considering that one pioneer of operational research, Patrick Blackett (later Baron Blackett, and later also featured in Thomas Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow), defined the pillars of OR as based on “observation, experiment and reasoning.”24 A broader understanding of the scientific method had been rolled out and integrated into how space, strategy, tactics (including the evaluation of the success of tactics), and logistics were to unfold based on data.

Nonetheless, to keep with Kahn’s exaggeration in spirit and style, perhaps OR did more for “theory” than French 1960s structuralism and poststructuralism.25 Perhaps not, and it is definitely not the sort of theory we usually practice or want to practice in the humanities, but one point was made clear: experience is secondary, formalizable design and planning are primary. To program the battlefield, you program people first, while later on you have programmable machines such as the ones that produce and analyze operational images as we know them now.

To deal with large-scale systems, logistics, and abstractions, one had to fine-tune a different mindset: “In decisions regarding weapons systems development such as choosing between long-range bombers with big fuel tanks or short-range bombers with refueling capacities, ‘no one can … answer by instinct, by feeling his pulse, by drawing on experience,’” as RAND economist Charlie Hitch put it.26 In short, the centrality of complex calculations (e.g., logistics), the massive amount of data to be processed, decisions to be taken, and the multiple scales of abstraction were not commensurable with the cognitive capacities of humans in the traditional sense of even trained officers. The necessity to be able to rationalize, theorize, model, and potentially automate decision-making in the context of complexity persisted from the war to the postwar period—for example, in management theory, making it a part of systems thinking where any decision was part of a meshwork of other decisions, by other actors, in a recursive loop.27 Cultural techniques of quantification connected to modelling were one particular route offered in this history of what “operations” came to mean on and off the battlefield. Numbers count landscapes and what moves through them; they count routes and their optimal relations; they count possibilities and potentials, and numbers are the backbone of both images and industrialization. Data is not infallible and simply “objective,” as critical data studies has shown over and again,28 but it can be effective whether it is correct or not. Rolling out data-driven decisions, systems, and operations is also an intervention in landscapes, social relations, values (financial and others), and more. These historical development are the implicit conditions of emergence for what Farocki called the “soft montage” of archive and inconsequential images.29 One peculiar context for such images is thus the over seventy-year history of military-driven operations research and subsequent management theory and some 150-year history of photographic-driven data analysis. In some ways, this all condenses into “an industrialisation of vision”30—or even “industrialisation of thought,”31 as Farocki himself characterized his interest in cinema and perception, directly echoing Virilio’s work on the “veritable market in synthetic perception.”32 The contemporary versions of this “industrialisation of thought” relate to questions of artificial intelligence and machine vision, but also to the genealogy of the concept of operations as it pertains to images, institutions, spaces, and nonhuman visuality.

The industrialization of vision has often been linked to the industrialization of destruction, a theme that connects Farocki to the theorization of war and visuality in the 1980s (and later).33 Much of this resonates with contemporary analyses of the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the role of images: “The operation of the image is defined by certain infrastructures,” writes Lesia Kulchynska in her take on the weaponization of visuality, drawing also on Anna Engelhardt’s research.34 As technical processes of abstraction, images that are primarily for targeting and destruction feature as part of a genealogy of rationalized violence that human bodies are subjected to. As such, Farocki’s take on operational images could be seen as a crystallization of much critical theory, thematically visible in his works that focus on the Holocaust, the Vietnam War (napalm in Inextinguishable Fire, 1969), the Gulf War, and the prison-surveillance-capitalist complex.35 But there needs to be nuance in how this concept of the operational image is read and used, avoiding the temptation to pack all sorts of abstractions—and abstract images of technical and calculational use—into one box, implying a kind of Enlightenment gone awry, a stream of violence and extraction that is merely about military power in the restricted sense of warfare. This is not to ignore the operational violence of capitalism or the colonial uses and functions of measurement and their neocolonial forms; but to take a position against abstraction on principle would be a mistake, leading us to insufficiently nuanced readings about technical images. We have plenty of those already, and in the context of environmental imaging, remote sensing, AI and platform culture, and many other crucial topics, we can no longer afford to miss the more detailed high-res insights.

In other words, I propose a shift from military operations to the other, closely aligned uses of force that define the current landscape of operations: “Operations Other than War.” This is not a nonmilitary form of power, but one that builds on particular logistical capacities and systemic, technological potentials of power primed for the contemporary planetary situation, from environmental issues to humanitarian assistance to the enforcement of exclusion zones to the handling of pandemics. In some ways this approach relates to the twentieth-century lineage of operations research, but it also becomes a way to tap into the contemporary logistical wiring of bodies and territories. In Rosi Braidotti and Matthew Fuller’s words, the

conflict is played out, triggered, and modulated through means that include finance, smuggling, culture, drugs, media and fabrication, technologies, resources, psychological operations, networks, international law, ecologies, economic aid, and urban terror. War becomes postdisciplinary, multiscalar, creative, and highly mediatic and technological, deploying specialized multiskilled teams and techniques.36

In other words, war and conflict become part of the extended repertoire of media techniques of confusion, doubt, and misinformation, often paired with the deployment of “ruses, proxies, ambiguous agency, hyperbole, the operationalization of ‘mistakes’ and unattributable forces.”37 Hence, we can ask: what format of operational images speak to this state of war and violence?

We might not (always) be at war, but we are (always) mobilized and operationalized. This could also be referred to as the perceptual and operational fine-tuning of the “nonbattle,” a term first introduced by Virilio and developed by Brian Massumi. Operations and actions are embedded in a broader field of intensities and potentials, possibilities, and the modeling of futures. “In the nonbattle, the relation between action and waiting has been inverted. Waiting no longer stretches between actions. Action breaks into waiting.”38 The operational is nested here in the significance of knowing how soft power can work effectively. Massumi continues: “Soft power is how you act militarily in waiting, when you are not yet tangibly acting … In the condition of nonbattle, when you have nothing on which to act tangibly, there is still one thing you can do: act on that condition. Act to change the conditions in which you wait.”39

Operations that act on the conditions of existence and on the conditions of further operations sound like a version of Virilio that Massumi restages. They also sound like a proposal that could come from the direction of Foucault’s analysis of architectures and diagrams. One could also consider images as tableaus of information40 (in reference to Gilles Deleuze’s terms) that cut across and rearrange traditional scales of experience, space, and meaning, such as the abstract images that rearrange today’s technological cities. Indeed, the Farocki in question here is somewhat less the critic of Enlightenment reason (in the lineage of Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer) and more the media archaeologist mapping what is visible, what is sayable, and importantly, what is countable. This line of argument shifts Farocki from a thematic analysis of modern rational images to a method of mapping archaeologies and genealogies of images as they become working material for critical thought. This material, though, is thoroughly conditioned by a recursive loop between industrial production and images in and out of war. Raymond Bellour calls this, rather aptly with a Foucault-inspired undertone, the “photo-diagram”—another phrasing of the methodological positions at play in operational images. Bellour’s note on Farocki’s material is fruitful for our purposes:

The photographs as well as the actual film recordings are equally ordered pieces of evidence of a reasoned assessment of the nature of the visible as defined on the basis of the very invisibilities that form it, leading to so many machinic and asubjective regulations, normativities and constraints.41

Operational images have been discussed in film studies by, for example, Volker Pantenburg, Thomas Elsaesser, Pasi Väliaho, and Erika Balsom, and in contemporary art discourse by Trevor Paglen, Hito Steyerl, and Lawrence Lek, among others. Many recent cinematic examples develop related insights and themes, such as All Light, Everywhere (2021) by Theo Anthony, the work of Geocinema, and the work of Beny Wagner and Sasha Litvintseva. Many others could be named, too. The Harun Farocki Institute in Berlin is institutionally significant in that it navigates among cinema, art, and discursive work as a “platform for researching [Farocki’s] visual and discursive practice and supporting new projects that engage with the past, present, and the future of image cultures.”42 Farocki’s name stands at the intersection of multiple genealogies, practices, and concepts that are not reducible to a story of an auteur. I do not claim that previous writing about him has done this either; Elsaesser already identified many of Farocki’s works as “contributions to media archaeology, as well as an essential part of the prehistory of digital images” where questions of interface, simulation, and, indeed, operation become central hinges for an appreciation of particular kinds of genealogies of which the digital is only one technical term. As Elsaesser puts it,

These changes we tend to associate with the digital turn, but operational images just remind us that moving as well as still images have many histories, not all of which pass through the cinema or belong to art history. Digital images may merely have made these parallel histories more palpably present, but operational images, as Farocki clearly saw, have always been part of the visual culture that surrounds us.43

Two intersecting, closely related points sum up this argument: On the one hand, “operational images” can be seen as a term that speaks to techniques of measurement, analysis, and synthesis through techniques of images but in particular institutional situations and uses. Operational images organize the world, but they also organize our sense and skills in terms of how we are trained to approach such images, from the photogrammetric mapping of landscapes to pattern recognition, from astronomy datasets to Mars Rover imaging practices. On the other hand, the term relates to practices (and labor) of testing, administering, and planning also reflected in the sites of filming where Farocki himself worked. These range from schools to offices to management-training centers and army field exercises, to paraphrase Elsaesser. To also quote his summary: “To operational images correspond operating instructions for life.”44 As instructions for life, operational images also imply a broader use of the term “algorithmic” as the training of bodies, the setting of institutional routines, and the rehearsing of automation in ways that tie machines to laboring human bodies. Imaging practices become operational in how they tie bodies into collective routines.

What characterizes Farocki’s films as investigating the “education image” (to quote Antje Ehmann and Kodwo Eshun) is exactly this quality of attending to “scenes that dramatize narratives of learning” and to material spaces, signs, and images that define learning (“work desks, typewriters, books, diagrams, and equations that constitute the scenographies of learning”).45 But after learning becomes about machine learning and training refers to the training set, we also have to adjust the scope of these cultural techniques. The work of labeling images in practices of supervised machine learning is one scene of the training of both neural networks and the people involved in sustaining those networks.46 The discourse of the photographic, but also the discourses of “education” and work, thus become restaged in ways that do not merely resemble the factory or the earlier use of the industrial scene, but as globally distributed across logistics platforms, such as Amazon Mechanical Turk.47 Not that one image replaces the other, but the educational image, navigational image, instructive image, and operational image take place at moments and sites of transition, exchange, and transformation. The electronic switch—and its relation to the circuit and circuit board, the techniques of control and optimization—defines the way both twentieth- and twenty-first-century operations and (technical) images become the historical site of connection.

In other words, societal operations are part of the broader framework of discussion of this particular aspect of visual culture, even if this at first seems in exact contrast to Farocki’s own somewhat fragmented description of operational images: “Images without a social goal, not for edification, not for reflection.”48 Farocki should not be taken to mean here that operational images are devoid of politics in relation to a variety of societal institutions. While such images are not interesting to look at as images, they are linked to a long chain of institutional, epistemological, and other uses that trigger a different aesthetics, one that speaks to questions of what is now, perhaps, called the nonhuman image49 and the nonrepresentational image as they circulate across institutional sites and uses, from education to training and the algorithmics of the everyday.

In summary: Operations and operationality are key concepts for contemporary visual and media theory even as they encompass more than just the visual, the visible, and the lensbased. The operational image is irreducible to being merely about digital images, big data, or artificial intelligence (machine/deep learning). These technologies are far from irrelevant, but they should be placed into a historical dialogue with questions of data, sensing, and spatial uses of images. The approach to operational images should be transdisciplinary, linking discussions in media theory, art studies, architecture, and critical infrastructure with visual culture studies. Shared concepts bind together different disciplines. Concepts, too, operate.

Annie J. Cannon, “Biographical Memoir of Solon Irving Bailey,” National Academy of Sciences, no. 15 (1932): 193.

J. Donald Fernie, “In Search of Better Skies: Harvard in Peru I,” American Scientist (September–October 2000): 398.

Fernie, “In Search of Better Skies,” 396.

Dr. Raimondi, quoted in Solon I. Bailey and Edward C. Pickering, “A Catalogue of 7222 Southern Stars Observed with the Meridian Photometer during the Years 1889–91,” Annals of the Astronomical Observatory of Harvard College, no. 34 (1895): 28.

Michelle Henning, Photography: The Unfettered Image (Routledge, 2017), 7.

Edward Pickering, quoted in Dava Sobel, The Glass Universe: How the Ladies of the Harvard Observatory Took the Measure of the Stars (Penguin Books, 2017), 38.

Annie J. Cannon and Edward C. Pickering, “Spectra of Bright Southern Stars Photographed with the 13-inch Boyden Telescope as Part of the Henry Draper Memorial,” Annals of Harvard College Observatory, no 28 (1901).

Kelley Wilder, Photography and Science (Reaktion Books, 2009), 34.

Wilder, Photography and Science, 31.

Wilder, Photography and Science, 34. Furthermore, it would be possible to expand to the longer history of engineering drawing where questions of measurement, techniques of descriptive geometry, and photogrammetry play a central role before such technical images as photography. In this sense, a media archaeology of operational images would become more about Gaspard Monge than François Arago or other pioneers of scientific photography. See Peter J. Booker, A History of Engineering Drawing (Northgate, 1979).

Harriett S. Leavitt, “1777 Variables in the Magellanic Clouds,” Annals of the Harvard College Observatory, no. 60 (1908): 87.

Leavitt, “1777 Variables,” 107.

John Durham Peters, Marvelous Clouds: Toward a Philosophy of Elemental Media (University of Chicago Press, 2015).

François Arago, “Rapport de M. Arago. (Seance du 5 juillet 1839),” in Historique et description des procedes du daguerreotype et du diorama, ed. LouisJacques-Mande Daguerre (Paris: Susse, 1839), 23–24. John Tresch, “The Daguerreotype’s First Frame: François Arago’s Moral Economy of Instruments,” Studies in History and Philosophy of Science, no. 38 (2007).

Wilder, Photography and Science.

Jimena Canales, A Tenth of a Second (University of Chicago Press, 2009).

Both “operative images” and “operational images” appear in English literature on the topic. The German term is operative Bilder.

See Florian Sprenger, Epistemologien des Umgebens: Zur Geschichte, Okologie und Biopolitik kilnstlicher Environments (Bielefeld: Transcript, 2019). On the somewhat connected notion of the “navigational image” that Doreen Mende has developed based on Farocki’s work, see Mende, “The Navigation Principle: Slow Image,” e-flux lectures, November 29, 2017.

Harun Farocki, “Phantom Images,” Public, no. 29 (2004), 18.

Farocki, “Phantom Images,” 18.

Farocki, “Phantom Images,” 18.

Sharon Ghamari-Tabrizi, The Worlds of Herman Kahn: The Intuitive Science of Thermonuclear War (Harvard University Press, 2005), 47.

Ghamari-Tabrizi, The Worlds of Herman Kahn, 48.

Patrick M. S. Blackett, “Operational Research,” Operational Research Quarterly 1, no. 1 (March 1950): 3.

See here also Bernard Dionysius Geoghegan, Code: From Information Theory to French Theory (Duke University Press, 2023).

Blackett, “Operational Research,” 3.

William Thomas, Rational Action: The Sciences of Policy in Britain and America, 1940–1960 (MIT Press, 2015), 216. Thomas’s book is a recommended entry point to the history of operations research.

A much longer bibliography could be listed, but examples of feminist data studies and related fields include Catherine D’lgnazio and Lauren F. Klein, Data Feminism (MIT Press, 2020); Jacqueline Wernimont, Numbered Lives: Life and Death in Quantum Media (MlT Press, 2019); and Uncertain Archives: Critical Keywords for Big Data, ed. Nanna Bonde Thylstrup et al. (MlT Press, 2021).

Harun Farocki, “Cross Influence / Soft Montage,” in Harun Farocki: Against What? Against Whom?, ed. Antje Ehmann and Kodwo Eshun (Koenig Books, 2009). See also Jussi Parikka and Abelardo GilFournier, “An Ecoaesthetic of Vegetal Surfaces: On Seed, Image, Ground as Soft Montage,” Journal of Visual Art Practice 20, no. 1–2 (2021).

Paul Virilio, The Vision Machine, trans. Julie Rose (Indiana University Press, 1994), 59.

Harun Farocki, “Industrialization of Thought,” Discourse: Journal for Theoretical Studies in Media and Culture, no. 15 (1993).

Virilio, The Vision Machine, 59.

Aud Sissel Hoel, “Operative Images: Inroads to a New Paradigm of Media Theory,” in Image-Action-Space: Situating the Screen in Visual Practice, ed. Luisa Feiersinger, Kathrin Friedrich, and Moritz Queisner (De Gruyter, 2018); and Paul Virilio, War and Cinema: Logistics of Perception, trans. Patrick Camiller (Verso, 1989).

Lesia Kulchynska, “Violence Is an Image: Weaponization of the Visuality During the War in Ukraine,” Institute of Network Cultures, October 26, 2022 →.

See Georges Didi-Huberman, “How to Open Your Eyes,” Harun Farocki.

Rosi Braidotti and Matthew Fuller, “The Posthumanities in an Era of Unexpected Consequences,” Theory, Culture & Society 36, no. 6 (2019): 7 (emphasis in the original).

Braidotti and Fuller, “The Posthumanities in an Era of Unexpected Consequences,” 8.

Brian Massumi, Ontopower: War, Powers, and the State of Perception (Duke University Press, 2015), 69.

Massumi, Ontopower, 69.

Tom Holert, “Tabular Images: On the Division of All Days (1970) and Something Self Explanatory (15 x) (1971),” in Harun Farocki, 92.

Raymond Bellour, “The Photo-Diagram” in Harun Farocki, 146. On Foucault and invisibilities, see also Gilles Deleuze, Foucault, trans. Sean Hand (University of Minnesota Press, 1988).

The Harun Farocki Institute website →.

Thomas Elsaesser, “Simulation and the Labour of Invisibility: Harun Farocki’s Life Manuals,” animation: an interdisciplinary journal 12, no. 3 (2017), 219.

Elsaesser, “Simulation,” 223.

Antje Ehmann and Kodwo Eshun, “A to Z of HF, or 26 introductions to HF,” in Harun Farocki, 206.

On machine learning and its learners, see Adrian Mackenzie, Machine Learners: Archaeology of a Data Practice (MIT Press, 2017).

See Joanna Zylinska, “Undigital Photography: Image-Making beyond Computation and AI,” in Photography Off the Scale, ed. Tomas Dvorak and Jussi Parikka (Edinburgh University Press, 2021).

Farocki in Eye/Machine I (2001), quoted in Volker Pantenburg, “Working Images: Harun Farocki and the Operational Image,” in Image Operations: Visual Media and Political Conflict, ed. Jens Eder and Charlotte Klonk (Manchester University Press, 2017), 49.

Joanna Zylinska, Nonhuman Photography (MIT Press, 2017).

Category

Subject

Research and writing have been supported by the Operational Images and Visual Culture project, funded by the Czech Science Foundation’s EXPRO grant 19-26865X.