In 2011, the critic David Teh described the state of video art in Southeast Asia as “embryonic.”1 This judgement, clearly signaling the potential and imminence of development, was expressed in the catalogue for the exhibition “Video, an Art, a History 1965–2010,” organized by the Singapore Art Museum in partnership with the Centre Pompidou in Paris.2 According to the curators, the exhibition sought to bring together divergent timelines of video art in a comparative and transnational survey. To accomplish this goal, an expansive range of work from both collections was assembled, including pieces by Valie Export, Araya Rasdjarmrearnsook, Apichatpong Weerasethakul, Trinh T. Minh-ha, Dan Graham, and The Propeller Group. As Teh’s comment demonstrates, it was a watershed moment for the Singapore museum and for the cultural sector of Southeast Asia in general. In his essay (revised in 2012 and 2017, expressing the development he pointed towards perhaps), Teh was optimistic about the shape of things to come.3 Writing from 2023, however, can it be argued that Southeast Asian video has outgrown that “embryonic” stage, arriving at a point where it can and must be viewed in equal terms with art produced in the West? This raises the further question of how to situate and historicize video art criticism in Southeast Asia, especially when an exhibition like “Video, an Art, a History” could only present an art historical survey of video art in the region through its comparison to art from the West. Is such a comparison beneficial or necessary? Could this show reveal the specificities of the “local” even under such comparative circumstances? Looking more deeply into Teh’s writing and the works he surveys allows for a different view into counter-historical and antagonistic tactics in art production. It becomes evident that in disavowing that form of comparative analysis, Teh wrestles with the “nation” only to advocate the somewhat contested idea of “Southeast Asia” as a framework in itself for theorizing art.

Araya Rasdjarmrearnsook, Two Planets: Manet’s Luncheon on the Grass and the Thai Villagers, 2008, 16 min. Video still.

1. Courting Censorship?

In a review of the first Singapore Biennale in 2006, Filipino critic Eileen Legaspi Ramirez argued that video artists in the region likely faced “censorship” from authorities. Writing in the online journal Ctrl+P, Ramirez indeed revealed that for this reason, the organizers of the exhibition were averse to “staging critically charged work.”4 After citing the press conference in which the organizing institution claimed that “political art in Southeast Asia [was] passé,” suggesting that such art was not welcome in the space, Ramirez pointed to video artist Brian Gothong Tan’s “cheeky video installation, We Live in a Dangerous World,” which dramatizes state capture. Tan’s installation included three video monitors and an ensemble of human-like sculptures appearing like a family on one side of a small proscenium; on the other side was a group of imposing, cloaked, zombie-like sculptures. Ramirez’s report on the 2006 Biennale resonates with another point by Teh: “For artists, however, the state’s stranglehold had long cheapened the moving image’s epistemological value; and they now seem disinclined to restore it, even where that grip has been relaxed.” He argues that the exception to this rule was Indonesia, where, “since the fall of Suharto in 1998 (reformasi), video art’s development has been inseparable from a wider flourishing of DIY culture, activist media collectives, and community video initiatives.”5 Here, Teh was referring to ruangrupa, one of a number of collectives in Southeast Asia who practiced tactics that he would later describe as “withdrawal,” “avoidance,” and “evasion.” Using this set of terms, interchangeably at times, Teh describes the video art of Southeast Asian artists who incorporate national or regional identity in their work, and yet simultaneously expose the violent mechanisms that undergird or inform state capture.

2. All History

For the most part, Teh’s criticism and art-historical analysis have been devoted to this idea of the “avoidance” of state capture, by which he means the delicate balance that Southeast Asian artists strike in both embracing their local and regional identities, and simultaneously exposing what Teh calls the “long shadow of authoritarianism” in the Southeast Asian art context.6 In his book Thai Art: Currencies of the Contemporary (2017), for example, he examines the work of artists like Arin Rungjang and Apichatpong Weerasethakul, which reveals “the precarious ways in which Thai art has been allied with either national or international contexts,” according to Clare Veale, while also pursuing “the possibility of understanding Thai art as simultaneously within and beyond the nation.”7 Teh demonstrates that video artists like Apichatpong were influenced by aesthetics and art movements outside of Thailand, including from the West, though they still hold the nation as a frame of reference.8

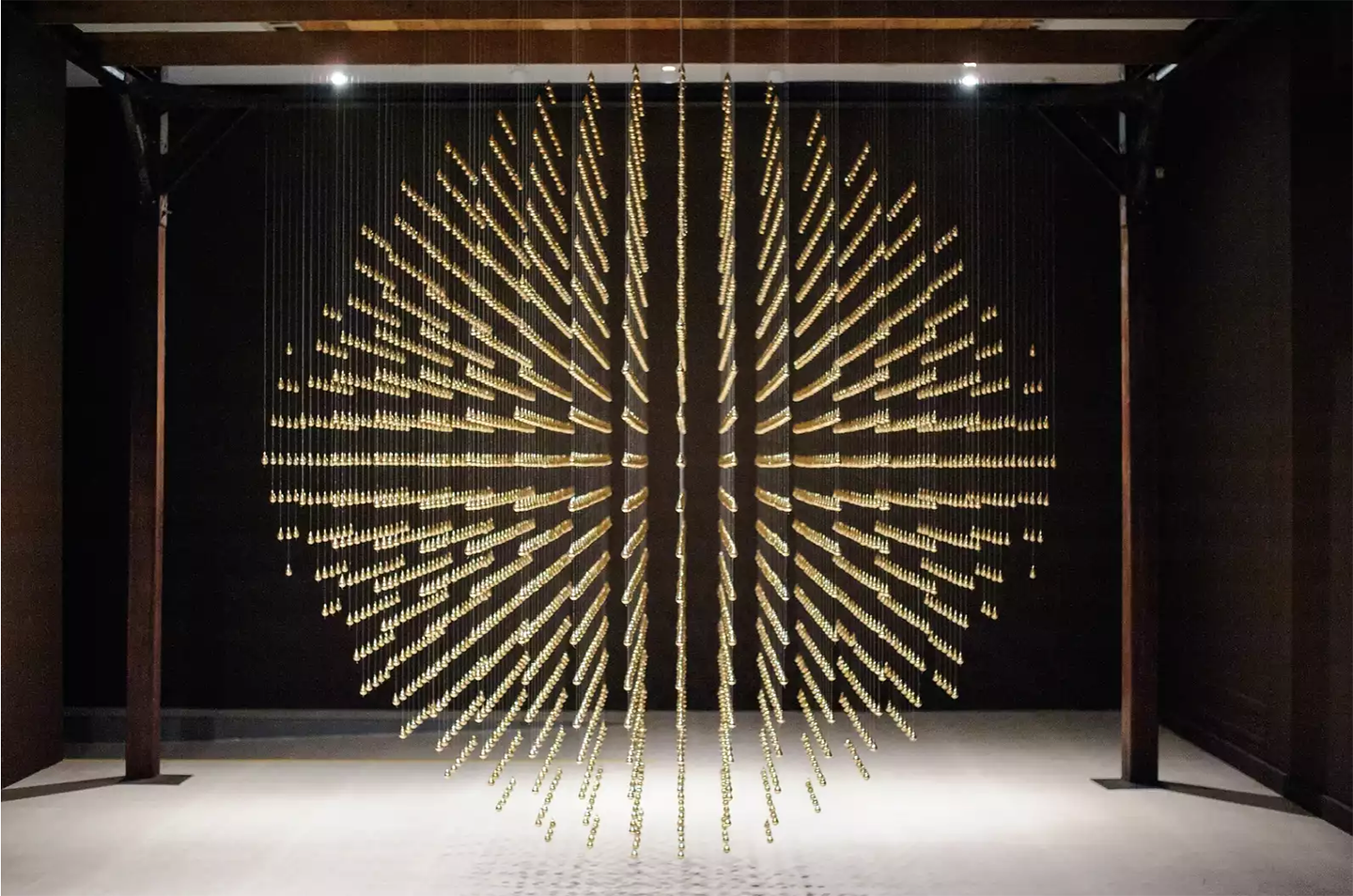

Arin Rungjang, Golden Teardrop, 2013. Singapore Art Museum.

Challenging the relevance of the “nation” as a paradigm for thinking art, Teh writes that “in Asia at least, the frame of national modernity has done less and less to illuminate the work of contemporary artists intent on stepping beyond it in various ways … Our task,” he continues, “therefore remains twofold: at once a counterhistory of the modern, and a history of the contemporary as such, in its new, supranational contexts.”9 This notion of the “supranational” appears in Teh’s writing as a salve or balm for the chaotic entrapment of state capture within which all history remains. But what is this all history?

In order to pursue his critique, Teh looks to older histories of the Southeast Asian region in order to cultivate a broader understanding of art that encompasses histories that predate the modern European and Asian nation-state forms. For example, Teh looks to Zomia, a shorthand for large portions of mainland Southeast Asia, which was studied by anthropologist James C. Scott.10 Scott argues that Zomia was economically and culturally outpaced by nation-states like the Republic of Singapore in the mid-twentieth century. In a 2017 essay citing Scott, Teh responds that “far from being luckless roadkill on the highways of national modernity, we might rather see the Zomians as partisans of a much older and ongoing struggle against all kinds of oppressive regulation, authors, by virtue of their cultures at least, of sophisticated programs of resistance to forces of economic and cultural simplification.”11 Thus, Teh raises the question of Zomia’s continued timeline, and how that timeline relates or acts to contest others, particularly the linear time of the modern nation-state.

Scott uses the term “escape agriculture” to describe the nomadic mixed culture of farming that upland Zomians practiced, after their escape from the lowlands. He positions Zomians as seeking refuge in highland areas in a way that recalls the upward settlement of Maroons in Haiti and Jamaica, and their fugitive tactics. However, I am interested in Teh’s formulation “luckless roadkill on the highways to modernity” as a way to critique Scott. Teh’s critique proposes that Zomia continues to exist, regardless of the (post)colonial maps of the region, while Scott summarily argues that just as the monoculture that came to define state capitalist industry during modern times took hold, the Zomians and their nomadic, diverse culture were killed off.12 This latter view appears more radical in its decisive destruction of Zomia with the advent of the modern nation-state. Its apocalyptic and eschatological premise confirms the violent conditions that birthed modernity. In this latter regard, I am reminded of the similarly anarchist position of Martinican psychoanalyst Frantz Fanon, who argued in his book The Wretched of the Earth for violence as a means of liberation from colonial rule.13

Zomia has also been taken up by other curators and critics as an example through which to think about the histories of colonization, enclosure, and state formation, if not exactly on those terms. For example, The Forest Curriculum, a curatorial collective made up of Abidjan Toto and Pujita Guha that works through radical pedagogy, took up Zomia as its major focal point. The collective proposes a “critique of the Anthropocene” through a championing of the farming cultures of Zomia.

3. What Kind of Cosmopolitanism?

Writing on the work of Apichatpong and Pratchaya Phinthong, who are both from Isaan, the northeast region of Thailand, Teh aims to recover what he refers to as a “cosmopolitan” modernity.14 This alternate cosmopolitanism, apart from Western bourgeois systems, developed over centuries and was in contact with Siam and Khmer. According to Teh, this alternate vision of multiethnic and cross-cultural diffusion was the result of the region serving as a land for resettled and displaced people. Thus, though he calls Isaan “cosmopolitan,” a term that signifies Western modernity to a degree, I would argue that modernity is temporally out of step with Isaan’s longue durée. In short, through the example of the people of Isaan, Teh inverts Scott’s version of a violent modernity, writing that

they have a long history of resisting political domination (and military conscription) by central Siamese bureaucracy, and economic domination by Sino-Thai agri-business and all that comes with it (debt and dispossession, privatization of genetic resources, reliance on costly and toxic pesticides—all the iniquities of big-time monoculture).15

Teh views Isaan ultimately through the lenses of “evasion,” “withdrawal,” and “avoidance” of state capture; that is, the same terms he uses to describe certain critical art practices, though in this case applied to the people of Isaan to describe their “cosmopolitanist” acts of resisting political domination. Another picture emerges from the artist Apichatpong, who says that this region speaks a common language. His films, which have drawn from communities in Khon Kaen, the place of his birth and one of the four major cities of Isaan, distill a local that projects a view of unification rather than fragmentation.

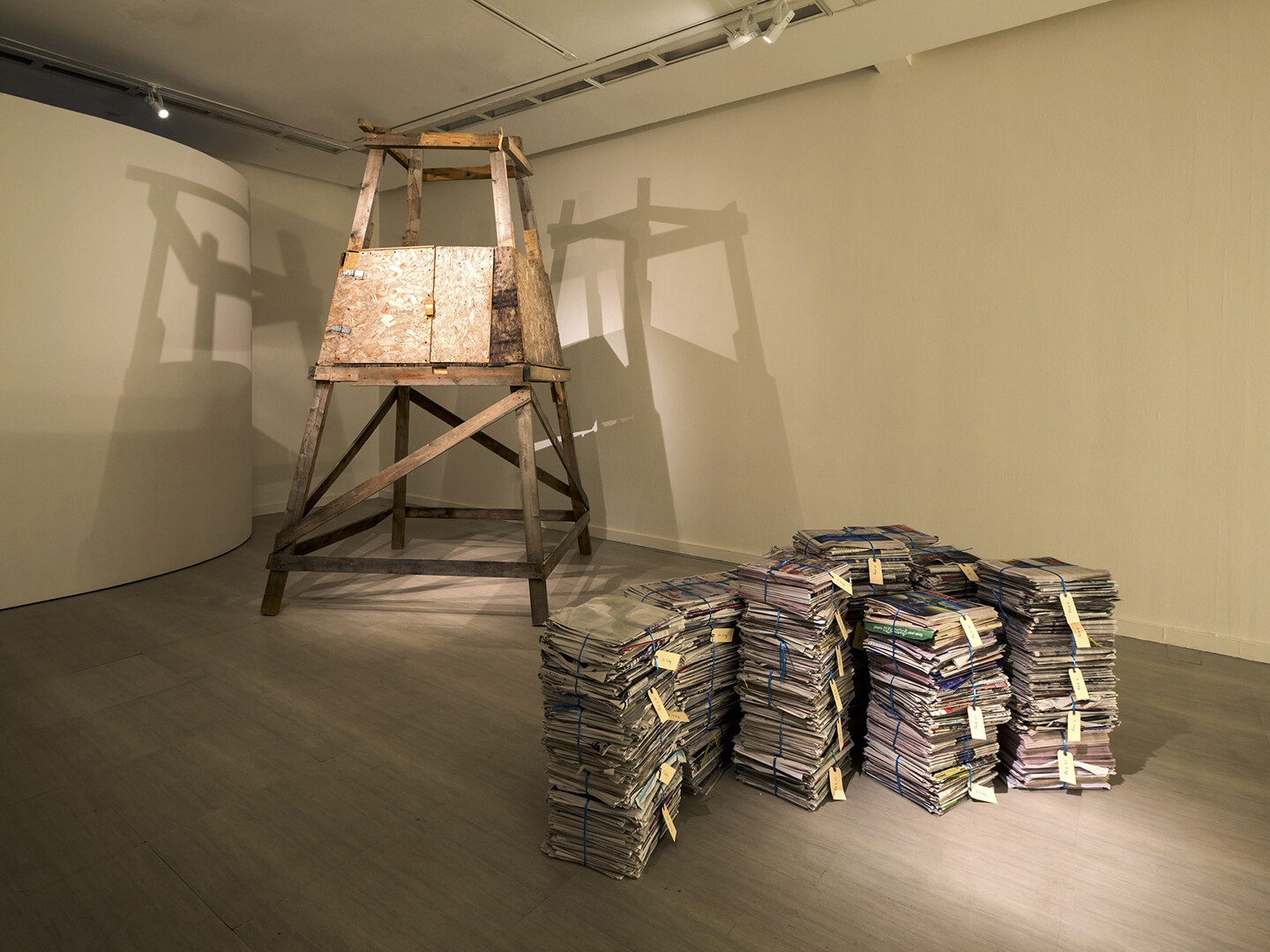

Pratchaya Phinthong, Give More Than You Take, 2010.

Elsewhere, the scene of migrant labor haunts the neat cosmopolitan frame that Teh conjures in his positive modernity coexisting with Zomia. After detailing the migrant agrarian workers in Isaan who feature in Pratchaya’s Give More Than You Take (2010), Teh refers to the roaming of these workers in the Nordic countries as chimerical. He also writes: “Despite extortion by unscrupulous brokers, they remove themselves from a poverty trap with clear ethno-national dimensions.”16 This labor perspective undermines the cosmopolitan frame in which Teh situates the Isaan workers. These nomadic Zomians, who once fled the lowlands for the uplands, and have now fled Southeast Asia for Europe, face the machinations of European statecraft and its maneuvers against the “freedom to roam.” One begins to wonder about their survival in the face of the radically globalized labor market that we encounter in Pratchaya’s video art.

4. State Iconography

In an interview, Teh suggests that artists in Southeast Asia like Rungjang and Apichatpong, and more recently Korakrit Arunanondchai, put forward a potent criticality (of the nation, of Western modernity) in their work.17 According to Teh, these artists expand the possibilities of art production, and expand infinitely the horizon of history in Thailand in ways that can effectively push back against the state machinery and its ventriloquism of the Bangkok Art Biennale. Once again, they exist both within and without this structure. Arguably, this attention to the artist as a critical thinker comes from Teh’s work as a curator in the mid-2000s in Thailand. (He curated the 2006 exhibition “Platform” at the Queen’s Gallery in Bangkok, which included Rungjang, among other artists. Teh later worked as an art dealer, selling work by Rungjang and other Thai artists.) This curatorial knowledge has shaped his criticism and art-historical writing. His intellectual formation was influenced by thinkers like Jacques Derrida, Georges Bataille, Jean Baudrillard, Martin Heidegger, and Walter Benjamin.18 Thus, his most potent engagement has been the critique of the political structure of the nation-state as it appears within the work of artists.19 Teh is generous in noting his influence from artists and their thinking, particularly in their attempts at recovering aspects of precolonial Southeast Asia and in their deconstruction of the modern nation-state (such as Thailand) via the foregrounding an alternative possible geography and/or imaginary.

Korakrit Arunanondchai, Songs for Dying, 2021, video. Photograph by Daniel Vincent Hansen. Courtesy of the artist.

Theorizing the video art of Singaporean artist Ho Tzu Nyen, Teh names allegory and narrative as a function of evasion, withdrawal, and avoidance. This is in line with his political aim to deconstruct the modern nation-state and its ideology. In several works by Ho, such as The Cloud of Unknowing, the artist actively draws from the “historical” partially by titling the video installation after an obscure liturgical text from the fourteenth century. Writing on The Cloud, curator June Yap notes, “Ho’s art confronts foundational myths and historical geopolitics, and deconstructs the idea of modernization via Western influence or beneficence, by presenting viewers with a paradox.”20 This deconstruction of modernity is what appeals most to Teh, who writes that “even at its most mythical, oneiric or philosophical, Ho’s work can be situated somewhere, but that somewhere is never a discrete, politically grounded site like a country.”21

Ho Tzu Nyen, The Cloud of Unknowing, 2011. Film still.

One of Ho’s mythical works focuses on tigers, specifically in the context of the Critical Dictionary of Southeast Asia (2012–present), a multimedia artwork. In it he forms an etymology for the term “T for Tiger.” His interest in Southeast Asia intersects with an interest in history. In this work, which became the basis for the exhibition “2 or 3 Tigers” at HKW in Berlin, he borrowed from “animist cosmologies that informed Southeast Asia.”22 More specifically, he deconstructed the idea of the modern city-state of Singapore by using iconographic narratives of the tiger that complicate the intersection(s) of Malaysian and Singaporean history. Stating that the tiger is thought of by Malays as an ancestor, Ho unsettles the mythical “lion” at the heart of Singapore:

Lions may be alien to the ecology of the lion city, but tigers were known to infest this little island and its surrounds. A creature much feared by the local inhabitants of the Malayan region, seldom was the tiger hailed by its proper name, harimau. Instead, locals referred to this terrible beast by a host of more colloquial substitute nouns, such as arimau, rimau, and rimo. These were terms that the anthropologist Peter Boomgaard described as being loose enough to encompass the sense of “big cat-like animals” such as leopards, which—like the tigers with which they were often confused, and unlike lions—were indigenous to this part of the world.23

5. Unknown Images

In light of these deconstructive readings, pace Derrida, we can consider Teh’s 2019 Artforum essay “Return to Sender,” which takes a very critical view of Thailand’s institutions of display, as expressed and exemplified by the Bangkok Art Biennale, while also praising the role of video artists in putting forward a “critical” view.24 Teh’s essay praises the work of artists like Korakrit Arunanondchai, particularly with regard to Ghost 2561, a performance and video series founded by the artist. Here we encounter Teh’s theorization of Southeast Asian video art when he describes the “hauntological” as one of the definitive elements of Korakrit’s practice. Elsewhere, the hauntological is immanent in Apichatpong. For Teh, the figure of the ghost complicates ideas of the self; in the works of the artists he discusses, the ghost doubles to enact a subjective consciousness that challenges linear temporality. At the same time, Teh argues viscerally against the purely formalist view of cinema studies that dare not venture into the content of works such as Apichatpong’s 2010 film Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives.25

Korakrit’s 2022 exhibition at Canal Projects in New York City referred to “poetics of radical consciousness, collectivity, and memory” that “emerge at the liminal space between living and dying.”26 His four spirit houses accompanying the installation reflect “portals” of communication with the living and dying. Similarly, Apichatpong’s Uncle Boonmee is based on the 1983 book A Man Who Can Recall His Past Lives by Buddhist monk Phra Sripariyattiweti, which raised a concern about the distinction between human and nonhuman, or between male and female, in the context of reincarnation.

Apichatpong is thus interested in the unconscious, and the dream, where we do not fully know or understand but have some idea of experience. If some would argue that Uncle Boonmee is purely focused on Eastern Buddhist thought and philosophy, I would point out the similarity of the artist’s approach to the work of nineteenth-century philosopher William James, who actively participated in seances, and whose radical empiricism and psychology took spiritual experience seriously. Following this latter example, both Korakrit and Apichatpong provide equally lucid but ultimately illegible and unknown images. Dreams are complex because they are not literal. Thus, both artists engage in an active interpretation of these dreams and visions—or to use James’s term, they engage in a “stream of consciousness.” As Teh wrote in 2011, drawing from French surrealism to explain Apichatpong’s experiments with consciousness,

For all the dreaminess of his films, the unconscious that Apichatpong taps—or that taps him—is as much collective as it is individual. This could suggest an affinity with the less strident politics found at the margins of the movement. His approach is perhaps better described as post-Surrealist, like that drift after 1930 towards a new sociology, that “vague orientation” described by Georges Bataille, born of “detachment from a society that was disintegrating because of individualism.”27

6. Global Economy

I have attempted in this text to articulate the central aims of Teh’s video criticism: to unsettle geographies in favor of historical and mythical imaginaries, to highlight the hauntological as an approach to memory and analysis, and to foreground narratives and allegories that unmake or destabilize the myths at the core of the founding of nation-states in Southeast Asia. These are concrete aims. When placed in view of the nascent history of video art in the region, they provide clues about the progress of the field, and at the same time, reflect how the field’s birth (thinking back to Teh’s “embryonic” comment) and expansion is entangled with the geopolitical and global economic forces of the region. If anything, the work of video artists in Southeast Asia shows us how much is yet to be overcome with regard to oppressive forces of global capitalism and state capture. What Ramirez wrote in her 2006 review of the Singapore Art Biennial sadly remains true: there is still a risk of “censorship.” If indeed the museum’s position has changed towards “staging critically charged work,” it could always lead to what Stefano Harney and Fred Moten articulate as the absorption of the critique by the institution, with its strategies of professionalization and enclosure—in short, recuperation in addition to censorship.28 What Teh shows us is that video artists are willing to perform their own evasions and withdrawals, and that these actions point towards alternate timelines, forms of contesting the vestiges of colonial expansion, and local counter-histories. Whether or not these aesthetic actions lead to any tangible political transformation is a question for a different day.

“Recalibrating Media: Three Theses on Video and Media Art in Southeast Asia,” in Video, an Art, a History 1965–2010: A Selection from the Centre Pompidou and Singapore Art Museum Collections, exh. cat. (Singapore Art Museum, 2011).

The curators described the show as “a pilot exhibition bringing together two institutional collections: one that began in France in 1976 with works from 1965 till today, the other since 2008 in Singapore; one turned towards major international trends, the other steered towards Asian works—more specifically those from the currently very prolific region of Southeast Asia.”

The revised versions were published as “SEA STATE: Notes on Video Art in Singapore,” in Moving On Asia 2004–2013, ed. Yeran Jang and Kim Jihye (Alternative Space LOOP, 2012); and “Insular Visions: Notes on Video Art in Singapore,” The Japan Foundation Asia Center Art Studies, vol. 3 (2017).

“The Singapore Art Biennale: Keeping Faith,” Ctrl+P, no. 4 (December 2006).

“Insular Visions.”

“Insular Visions.”

Veale, “Thai Art: Currencies of the Contemporary,” Sojourn: Journal of Social Issues in Southeast Asia 33, no. 3 (November 2018).

Teh, “Itinerant Cinema: The Social Surrealism of Apichatpong Weerasethakul,” Third Text 25, no. 5 (September 2011).

“Introduction,” in Thai Art: Currencies of the Contemporary (MIT Press, 2017), 2.

The Art of Not Being Governed: An Anarchist History of Southeast Asia (National University of Singapore Press, 2010).

“The Fugitive Reflex: Autonomy and Sublimation After Zomia,” in 2 or 3 Tigers, exh. cat., ed. Anselm Franke and Hyunjin Kim (Haus der Kulturen der Welt, 2017).

Teh, interview by Serubiri Moses conducted via Zoom, January 4, 2023.

“Concerning Violence,” in The Wretched of the Earth, trans. Richard Philcox (Grove Press, 2004).

“Fugitive Reflex.”

“Fugitive Reflex.”

“Fugitive Reflex.”

Interview by Moses.

Teh, interview by Moses.

Veale, “Thai Art.”

“Ho Tzu Nyen, The Cloud of Unknowing,” guggenheim.org →.

“Under One or Several Flags,” Afterall, no. 51 (Summer 2021).

“(2020 Forum) 호 추 니엔 Ho Tzu Nyen,” Vimeo video →.

Ho Tzu Nyen, “Every Cat in History is I,” in 2 or 3 Tigers.

See →.

“Itinerant Cinema.”

From the press release →.

“Itinerant Cinema.”

“The University and the Undercommons,” chap. 2 in The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning & Black Study (Minor Compositions, 2013).