Introduction

“Wake up, big head!” a woman shouts at me after turning on the lights in the room where I was fast asleep. It’s 1:30 in the morning, and I let out a groan to express my annoyance with being woken up and reminded of the size of my head—a longstanding source of insecurity. “Get up and put on these shoes,” Giana tells me with a smile. I look at the shoes and discover that they’re the newly released Air Jordan Retros in red and white with black patent leather. I leap up with juvenile excitement from the couch where I sleep, and hug Giana before starting to get ready.

Although I did not yet know where we were going, I was ecstatic to wear the shoes I’d always wanted but was prohibited from having up to that point. I did not care how they were acquired.

I was fourteen years old and staying with Giana, Breah, and Sydney—a Latinx transgender woman and two Black transwomen respectively—in the two-bedroom apartment they shared in Chicago’s South Shore neighborhood. My parents had recently demanded that I leave their residence following my admission of my queer (gay at the time) sexuality and nonnormative gender embodiment. They remained incredulous that I would “choose” to walk down an abominable path of “rebellion and destruction” despite my Pentecostal upbringing. I gathered all the money I had to purchase a one-way ticket from my hometown (Bloomington, Illinois) to Chicago, where I met the aforementioned transwomen—an encounter that would save and change my life forever.

I asked all three women where exactly we were going while en route, but they were too busy talking to each other in what sounded like a foreign language to me. I heard them say words like “banjy,” “realness,” and even the word “cunt,” at which I gasped—I never thought these women would use such a slur. “Oh chile, you ‘bout to learn a lot tonight,” Sydney told me with a chuckle as she rubbed the top of my (big) head.

We soon arrived at the venue, which at first glance appeared to be a high school. We walked around the school to a building with an oversized front door, and suddenly I felt the bass pulsating. The next thing I knew, I was surrounded by Black and brown people who dressed better than I did—a new experience for me—and who were clearly unafraid to be themselves. Several of the women were beyond beautiful and wore dresses that looked like those I’d only seen in fashion magazines. Some people appeared to be practicing a dance that I’d seen on YouTube when I typed in “Black gay people.” Some chatted and hugged friends, but I stayed close to Breah for most of the night. I was shy despite my excitement to be in the same space as so many other Black and brown people who also appeared to be just as queer as I was.

This was to be my first ball. As it started, people began chanting things that didn’t make sense to me. I asked Breah, who said, “This is what’s called LSS, boo. You’re a virgin at your first ball, so just try to take in as much as you can; you’ll soon come to appreciate and love all that you see here tonight.” At the time, I did not know just how right she was.

***

The ballroom scene is a cultural formation comprised of (mostly) urban Black and brown lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ+) people who join “houses” and compete against members of other houses in myriad competitive categories—including runway, fashion, realness, face, and performance—for prizes ranging from trophies to $100,000. Beyond the competitive floor, the scene provides its members with transformative opportunities and experiences of kinship structures and gender systems that defy normative assumptions and formations. Ballroom provides a family and community for many people in the scene who are otherwise routinely denied such relationships and experiences due to family rejection, sexism, transphobia, and homophobia. Many scene members regularly experience transience, poverty, and violence (sexual, physical, mental, emotional, and spiritual). The ballroom scene is a space for community members to momentarily set aside the issues they face and celebrate themselves and each other while present at the ball.

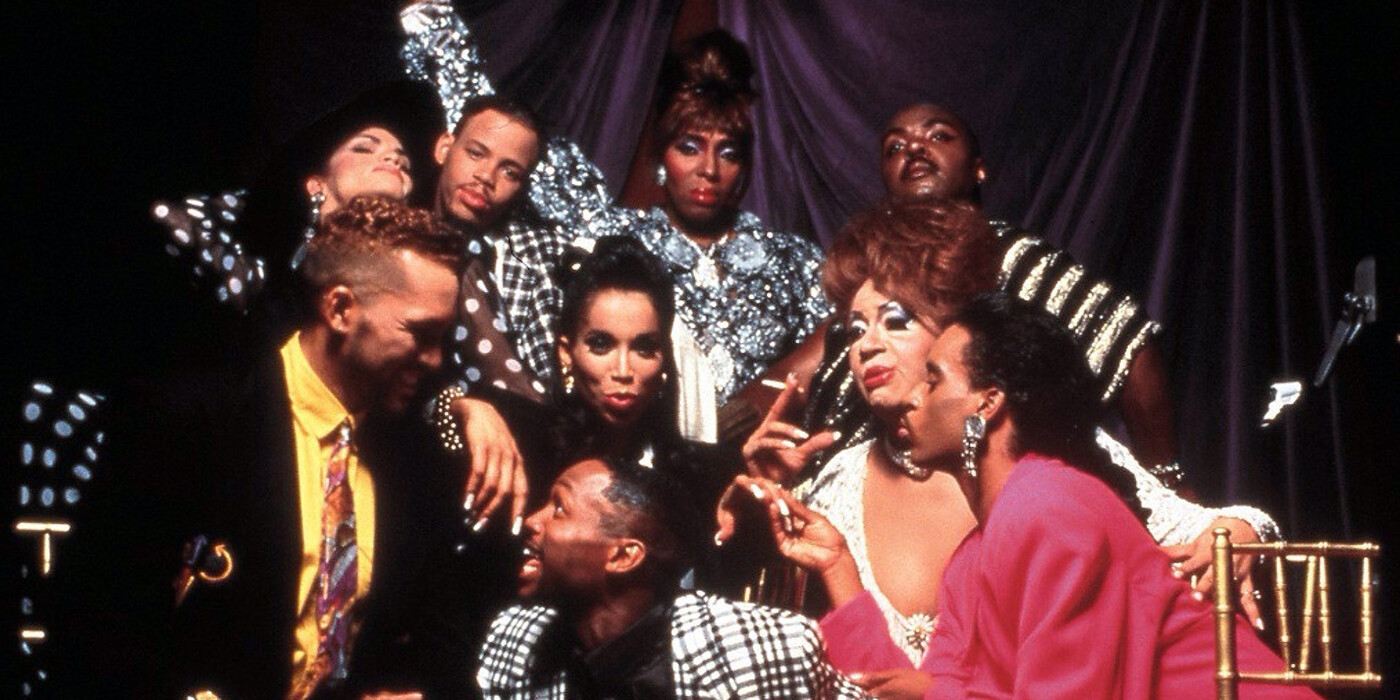

Ballroom’s contributions to global popular culture are innumerable. Entertainers, celebrities, and musicians (e.g., Madonna, Beyoncé, Rihanna) continually seek inspiration, collaborative opportunities, and guidance from those in the scene. The recent proliferation of award-winning television shows including Pose and Legendary provide further evidence of the scene’s influence. Jennie Livingston’s 1990 documentary Paris Is Burning remains one of the most well-known and highly contested depictions of the scene, and is even considered to be a quintessential piece of queer cinema.1 RuPaul’s Drag Race, a hit since it first aired in 2009, includes a “reading” challenge in a purported homage to ballroom. While many within the scene welcome the ensuing influx of new people and media, others are more reluctant to receive newcomers without the proper vetting processes.

Given the barrage of media representation and rising popularity across social media, how might the ballroom scene continue to honor and hold space for the foundational contributions of its progenitors—Black and brown LGBTQ+ people—who’ve long comprised the majority of the scene’s membership? How might the flood of new people (from a wide array of cultural backgrounds) complicate or challenge the ritual performances and traditions which anchor the scene? I wonder how the ballroom scene might continue centering its Black and brown members—whose input remains integral to the scene as we know it today—while also making room for the beloved cultural formation to grow in unanticipated and potentially generative ways.

The stakes are high; the influx of newcomers risks diluting the standards for what constitutes a bona fide performance. In recent years, the slippage between cultural appreciation and appropriation prompted Leiomy Maldonado, a ballroom icon, model, choreographer, and judge on Legendary, to caution against the rise of what she calls “No-guing.” This term refers to “any choreographer or dancer who attempts to display voguing with no knowledge of Vogue nor training which often comes off like a mockery.”2 Maldonado’s rebuke constitutes a form of gatekeeping to shield the meaning and significance of voguing—one of the ballroom scene’s quintessential and most revered cultural contributions—from appropriation.

Gatekeeping is not the only tactic that the ballroom scene deploys to stave off appropriation. Despite newcomers, the scene maintains an insularity that buffers it from such exposure. This insularity manifests through specific aspects associated with the scene’s ritual performance which, I argue, create a transformative ecosystem through its generative engagement across sonic, vocal, and kinesthetic registers. This ecosystem provides affirming, sustaining, and meaningful embodied experiences for the scene’s Black and brown LGBTQ+ members who are bombarded by societal messages suggesting that our lives are wholly devoid of purpose or significance. Further, this ecosystem remains inextricably linked to the lived experiences that shape ballroom’s ritual performances.

In ballroom, the beat, the voice, and the floor each cultivate sonic, vocal, and kinesthetic forms of refusal, resistance, and resilience, which together conjure an embodied knowledge that cannot be taught or copied by those who do not share similar experiences—shielding the scene and its contributions from being wholly consumed by trends within popular culture.

The Beat

Of the elements that comprise the ballroom scene, its relationship to sound is one of the most recognizable. The beat in ballroom creates a Black queer frequency, remixing existing sounds to conjure new sounds that disrupt normative musical expectations (in terms of form) and provide the basis for a sonic experience which directly connects its progenitors with their community to cocreate new possibilities. By refusing to conform to normative expectations of musical form, the beat in ballroom presents a mode of refusal which centers the desires and interests of the scene’s membership. This form of sonic refusal holds space for ballroom members to imagine new ways of knowing and create unique sonic and kinesthetic relationships that facilitate the exploration of previously foreclosed possibilities to determine the significance and meaning of a range of experiences for themselves.

Perhaps the most famous beat emerging from the ballroom scene is “The Ha Dance” by Masters at Work, a 1991 collaboration between producers “Little” Louie Vega and Kenny “Dope” Gonzalez. The beat features a repeated vocal triplet and a subsequent percussive crash/clap that lands on the fourth beat of each measure. A syncopated rhythm layers on top of the opening. The combination provides the basis for the rest of the song, which notably features no lyrics. Gonzalez, speaking in 2016 about how he and Vega created the beat, says, “At the time Louie was playing in predominantly Latin clubs so everything was harder … That joint, we did it for that crowd. But it became a voguing classic, which is crazy because it wasn’t made for that but they embraced it.”3 In the same conversation, legendary ballroom DJ MikeQ references the late Vjuan Allure—another legend who made his name playing house tracks during balls in the 1990s—who told MikeQ that despite bringing an array of records to each ball, scene members wanted “only” to hear “The Ha Dance” “all night,” which ultimately prompted Allure to remix the Ha into different tracks. Vega remembers how members of the scene began attending the Latin clubs he played; the Ha had become their anthem and remains so to this day.

The Ha’s creation and sound offer important lessons about ballroom’s relationship to sonic register. The creation of the Ha—the quintessential ballroom beat—reveals that the scene’s signature sound is a cultural production characterized by sonic hybridity—that is, the strategic mixing and remixing of culturally significant artifacts to create new soundscapes for specific audiences. For example, the vocal crash/clap that animates the Ha, according to Vega and Gonzalez, emerges from a short segment in the 1983 film Trading Places starring Eddie Murphy and Dan Aykroyd.4 Originally intended to provide comic relief, Vega and Gonzalez remix the Trading Places sound bite and in so doing, alter its meaning, function, and purpose so that it takes on a whole new life in the contexts of Latin clubs and the ballroom scene. It is no surprise that the progenitors of the Ha themselves emerge from urban Black and brown communities which also practice various forms of cultural hybridity. Such practice is central to the cultivation of Black and brown life.

The Ha’s sound underscores how the ballroom scene harnesses the sonic realm to conjure a Black queer frequency which disrupts normative musical expectations. The Ha features no vocals and adopts a repetitive form, which distinguishes it from the expectations that rule most Western music. It refuses an easily distinguishable sonic arc—which works akin to a narrative arc with a clear beginning, middle, and end—that contains an exposition, development, and recapitulation (sonata form). The beat in ballroom provides the basis for members to shape and tell their own stories by getting in tune with a distinct Black queer frequency. The ballroom scene’s rebuke of hegemonic musical forms has implications for its relationship to another highly contested subject among Black studies scholars: time.5

The ballroom scene’s Black queer frequency sonically creates opportunities for its members to refuse understanding themselves and their journeys in accordance with linear notions of time (past, present, and future) and hegemonic conceptions of “progress.” Ballroom’s Black queer frequency enables its Black and brown members to create, cocreate, mix, and remix their own stories and the meanings derived from their embodied knowledge in ways that measure “progress” as a process of continual transformation rather than a final product.

One example of this comes from Vjuan Allure’s 2017 ThundaKats EP, on a song called “Reclaiming My Time.” The track uses vocal samples from a famous 2017 US House of Representatives meeting during which Congresswoman Maxine Waters, upon receiving unsatisfactory responses to her questions from then US Secretary of the Treasury Steve Mnuchin, repeatedly used the phrase “reclaiming my time.” The song begins with a simple drumbeat, animated by cowbell and Allure’s vocal tag (used by DJs and producers to identify themselves on a track), before listeners hear the first vocal sample of Waters’s phrase “reclaiming my time.” That is soon followed by Congresswoman Waters saying, “What he failed to tell you was that when you’re on my time, I can reclaim it.” The next portion of the song develops the beat by remixing and shortening various words in both samples in a way that accents the track’s overall message and even uses a brief vocal sample from Mnuchin, who repeats: “I was gonna answer that.”

The accumulated sonic effect of the repeated phrases “reclaiming my time” and “I can reclaim it” drive home how the scene’s Black queer frequency expresses its conception of time and its ongoing commitment to doing so. The scene’s sonic refusal to acquiesce to externally defined expectations and standards related to time puts its members in charge of what time means as a basis for exploring new communal possibilities of relationships between time and space. The scene’s sonic refusal also opens an opportunity to make, remake, and play with time in generative ways that bolster agency. Allure’s track also demonstrates how—similar to space as theorized by gender, sexuality, and performance theorist Marlon Bailey—time within the ballroom scene is a cultural production defined and redefined indefinitely by its membership, thus allowing members to tell new stories, remix existing ones, and cocreate culture.6

The Voice

Ballroom’s ritual performance also invokes the voice—another constitutive element of its ecosystem—and requires that an emcee, usually called a “commentator,” be present throughout the ball.7 The commentator’s job is multifaceted: they serve as master of ceremony, preside over LSS (legends, statements, and stars), announce the order of categories, tally votes, and chant during battles.8 As one might imagine, being a commentator in the ballroom scene can be exhausting given the sheer number of balls that happen and how long each ball lasts (anywhere between six and eight hours). Commentators also provide an abundance of energy to competitors and audiences alike. This energy can be potent enough that it empowers competitors to give electrifying performances and prompts the audience, usually called “spectators,” to share in the excitement of the moment. A handful of commentators, including icons Jack Gucci (Overall Father of the House of Gorgeous Gucci) and Selvin/MC Debra Alain Mikli, are renowned as pioneers of the practice. Other well-known commentators include legendary Snookie West, Princess Precious, and Kevin JZ Prodigy, whose style caught the ear of an international superstar this year.

Commentators in the ballroom scene play a critical role in shaping what resistance to the myriad material and discursive manifestations of anti-Black, transphobic, and homophobic violence sounds like. Commentators use their voices to acknowledge the ubiquity of quotidian violence that they experience daily. They refuse both the terms of and continuation of their subjection, and articulate self-determined understandings of themselves and each other. Commentators demonstrate resistance as an active and ongoing process that requires a fervent commitment to personal and social transformation. Repetition characterizes this sonic process and represents the struggle to overcome dominant discursive narratives, which too often tether our lives to gratuitous violence and dispossession in an attempt to limit, constrain, and annihilate the possibility of a meaningful life.

Reappropriating language remains one of the primary tactics that commentators use to express various feelings and highlight important aspects of themselves and the larger ballroom community. Consider the scene’s usage of the word “cunt.” While the term retains an overwhelmingly pejorative connotation in America, ballroom’s invocation of the term hails it for an entirely different reason. Within the scene, “cunt” means ultra-feminine and is the highest compliment a person who embodies femininity can receive. There is an entire style of vogue femme—the ballroom scene’s hallmark dance form—called “soft ‘n cunt,” where voguers strive to exude a performance defined by slow, graceful, delicate, and highly controlled movements associated with femininity. This is just one example of how the ballroom scene reappropriates language to enable generative, restorative, and complex conceptions which cannot be easily reduced or deciphered by those who do not share similar life experiences.

The song “Feels Like” by DJ MikeQ, featuring Kevin JZ Prodigy, offers an example of what is generative about ballroom’s reliance on the voice to deploy its sonic refusal. Throughout the first part of the song, Prodigy repeats the words “feminine,” “pussy,” and “cunt” atop a beat which includes the scene’s signature crash/clap every four beats. Prodigy mixes the words in alongside vocalizations where the icon meows like a cat, performs a series of tongue rolls, and scats akin to jazz singers. Lyrics do not emerge until the latter half, where Prodigy repeats “feels like” again, differently each time, like a theme with endless variations. Then, expressing frustration, he adds the phrase “feels like I’m going in circles, feels like a maze, I can’t get through.” Prodigy continues asking himself, “Should I go, should I go, should I go left? Should I go, should I go, should I go right?” Nearing the end, Prodigy resists providing a response with words; rather, he uses a series of rapid percussive vocalizations which resemble the sound of a machine gun before ending the song with a recapitulation of the “feels like” lyrical phrase.

Prodigy’s voice in “Feels Like” constitutes a form of sonic resistance to the various forms of oppression to which his Black queer body render him subject. At the start of the track, Prodigy utters the word “feminine” in a highly distorted tone with an abundance of reverberation, which I read as a sonic manifestation of the fungibility of Black gender and its lack of “symbolic integrity.” Through this, the term remains open to myriad meanings.9 I read Prodigy’s articulation of “going in circles” which feel “like a maze” as a type of existential disorientation derived from his experiences as a Black queer person living in Philadelphia. His questions about which direction he should go offer more evidence of confusion, as any path he treads will likely be as full of danger and risk as it is opportunity. The rapid and percussive nature of Prodigy’s response provides evidence of his will to break down the walls of the maze by any means necessary. It is as if he took a sonic jackhammer to the discursive maze, to emerge from it and dispel the bewilderment that once trapped him.

Kevin JZ Prodigy’s sonic resistance continually reverberates throughout and beyond the ballroom scene. Beyoncé acknowledges this power by sampling Prodigy’s voice (specifically a snippet from “Feels Like”) on the track “PURE/HONEY” on her 2022 album Renaissance—yet another example of ballroom’s influence on popular culture across the globe.

Prodigy’s repeated sonic attacks against the convergence of racial, gender, sexual, and class subjugation conjure an effective tactic that members of the ballroom scene use to combat this discursive inheritance. In redeploying language rife with pejorative connotations for their own purposes, especially “pussy” and “cunt,” they choose to embody all that heteronormative society abhors. The cultural complexities of Black life render it physically, spiritually, mentally, and emotionally risky for Black people assigned male at birth to embody femininity. The sonic strategies of folks in ballroom respond to the charge that Hortense Spillers, in her seminal essay “Mama’s Baby, Papa’s Maybe: An American Grammar Book,” invites Black men to consider: “It is the heritage of the mother that the African American male must regain as an aspect of his own personhood—the power of ‘yes’ to the ‘female’ within.”10 Spillers’s call suggests that Black people, especially all those who embody masculinity (irrespective of sex assigned at birth), are most whole when both femininity and masculinity coexist.

Sinia Alaïa vogues

The Floor

The floor in ballroom enables community members to leverage kinesthetic knowledge to tell idiosyncratic stories of resilience that showcase thriving despite relentless exposure to myriad manifestations of violence. In the scene, the floor serves multiple purposes and takes on multiple forms, with the most recognizable ones emanating from runway and vogue. Runway categories in ballroom encourage members to model their outfit, usually called an “effect,” by strutting up and down the catwalk for the judges and spectators to see while also “throwing shade” at their competitors. Shade, in this context, includes nonverbal insults like taking gigantic steps in front/to the side of their competition on the runway or using an aspect of their effect to block a competitor from being visible.

Vogue, the other form of ballroom movement, is an improvisatory form of dance with multiple styles including old-way vogue (with its focus on symmetry, lines, and precision and influenced by poses in fashion magazines and martial arts), new-way vogue (with limb contortions at the joints, called “clicks,” and hand/wrist illusions called “arms control”), and vogue femme (heavily influenced by jazz, ballet, and modern dance, with an emphasis on fluidity, the expression of movements considered “feminine,” and the five elements—spins/dips, catwalk, duckwalk, hands, and floor performance).

All these styles of vogue emphasize telling one’s own story through movement. The most well-respected voguers are those whose kinesthetic expression of their stories are unique to them and immediately recognizable to competitors and knowledgeable spectators. The performance of a true master of vogue will be distinguishable to viewers even if their entire body was to be concealed. As one might expect, few within the ballroom scene achieve such a level of mastery. Those who do provide compelling evidence of the significance and meaning of their lives.

The kinesthetic expression of the late ballroom icon Yolanda Jourdan provides a salient example of how scene members uniquely express themselves through movement on the floor. Yolanda became known within the ballroom scene as “the 90s It Girl” through her innovative approach to voguing.11 Yolanda’s chosen style was vogue femme dramatics—characterized by stunts, tricks, and speed while executing the five elements. She was the first to introduce stunts including painting her nails and crossing herself (as in some Christian traditions) before a dip. Yolanda’s confrontational style distinguished her from the other femme queens—ballroom terminology describing a transgender woman undergoing medical transition. Prior femme queens usually emphasized their femininity by being as demure and sexy as possible. Yolanda’s kinesthetic expression strategically deployed signifiers of aggressiveness, which are associated with masculinity, in tandem with those associated with femininity, such as painting one’s nails. She demonstrated being confrontational while retaining her femininity, thus bringing together parts of her own complex story.

Over time, Yolanda’s performance cemented her story and status as an official icon within the ballroom scene. Everyone knew who she was whenever she entered the room. Consider a clip from a regular vogue night in New York City during which Kevin JZ Prodigy, the evening’s commentator, called Yolanda out to the floor, proclaiming her performance to be “o-ri-gin-al!” and Yolanda to be the scene’s sole “bitch who paints her muthafuckin’ nails!”12 With Major Lazer’s “Pon De Floor” playing, the video shows spectators progressively clapping their hands in anticipation of Yolanda before she graces the floor—a warm reception given only to a handful of other people within the scene. Yolanda enters and begins her performance with hands while a spectator holds her drink and handbag. She then directly faces Kevin, who immediately begins chanting. Yolanda’s performance captivates the audience within the span of two eight-count beats. The icon serves hands before tossing her hair and reaching up with both arms, as if she were bracing to catch something high above her head, only to subsequently ease into a dip. The audience’s excitement reaches a fever pitch as the video reveals how seemingly everyone in the building followed Yolanda to the ground, marking her dip with a bellowing “HA!”—the ultimate demonstration of her compelling tale. The dip punctuates her kinesthetic story like an exclamation point at the end of a sentence.

Yolanda is part of a select group of people within the ballroom scene whose kinesthetic brilliance continually sets the bar for subsequent generations. Two more recent short clips of icon Leiomy Maldonado voguing and imitating a handful of legendary femme queens show the unparalleled corporeal contributions of transwomen to ballroom.13 In the clips, Leiomy imitates women including Alyssa LaPerla, Roxy Prodigy, Yolanda Jourdan, Daesja LaPerla, Alloura Jourdan Zion, Meeka AlphaOmega, Sinia Alaïa, and Ashley Icon. I include these pioneers of vogue femme as their specific contributions illuminate how transgender women remain central to the ballroom scene. The power of such a genealogy cannot be erased or overlooked, and the ballroom scene would not be what it is without transgender women continually shaping the scene.

Leiomy’s example demonstrates the transformative potential of the floor in ballroom as it enables her to preserve the memory of the scene’s icons and their respective contributions through a loving kinesthetic tribute. The floor becomes a space of possibility through which Black LGBTQ+ people rejuvenate, inoculate, and celebrate ourselves and each other for attributes and accomplishments we imbue with significance. These conjurings reveal a truly diasporic Black practice as our traditions find strength in oral, sonic, and embodied—rather than solely written—modes of expression. The ingenuity of this rich lineage suggests that its vitality will live far beyond the current moment, thus keeping alive the memories and practices of the scene’s progenitors and offering salient connections to other manifestations of Black raves, nightlife, party, and dance cultures.

Conclusion

The ballroom scene harnesses the power of the beat, the voice, and the floor to create spaces of refusal, resistance, and resilience. Black and brown LGBTQ+ members craft and cultivate their own stories that honor the depth, breadth, and meaning of their contributions. Their stories reveal the importance of speaking truth to power, determining the meaning of one’s life on one’s own terms, and what doing so looks like along sonic, vocal, and kinesthetic registers.

The legends and icons of the scene conjure memorable moments too numerous to name. The ephemeral nature of their contributions does not present a weakness. Instead, it demonstrates how space for these moments remains a cultural production undergirded by preserving the scene’s emphasis on ritual performance. The knowledge and practice of its traditions are passed to subsequent generations through oral, sonic, and kinesthetic modes. The dissemination of knowledge through such arich ritual performance traditions places the ballroom scene beyond those privileged within Western societies, which prioritize written forms of knowledge. It also insulates the scene’s traditions from being wholly colonized by those whose remain (self-)interested in the glamor of the scene, but are not invested in its membership.

I concur with the late Vjuan Allure’s unbothered demeanor and lack of concern about the widespread appropriation of the ballroom scene, which he shared during a 2016 panel at the Smithsonian Museum of African Art. The complex and capacious nature of ballroom, according to Allure, provides evidence of how it cannot be appropriated: by the time the masses learn something “new” from ballroom, the scene has long moved on. In this way, the ballroom scene is like a whale that mostly dwells underwater, tending to itself, until it briefly emerges and makes a splash that captures the attention of everything and everyone around it. While those above still feel the impact of the whale’s ripples, it quietly returns underwater, wholly unbothered, to care for itself once again.

Lucas Hildebrand, Paris Is Burning: A Queer Film Classic (Arsenal Pulp Press, 2013).

Leiomy Maldonado (@leiomy), Twitter, August 22, 2020, 8:20 p.m. →.

Red Bull Music Academy, “Masters at Work and MikeQ on the Strange Life of ‘The Ha Dance,’” YouTube video, February 27, 2019 →.

Red Bull Music Academy, “Masters at Work and MikeQ.”

Kodwo Eshun, More Brilliant Than the Sun: Adventures in Sonic Fiction (Verso, 2018); Alexnder G. Weheliye, Phonographies: Grooves in sonic Afro-modernity (Duke University Press, 2005).

Marlon M. Bailey, “Engendering Space: Ballroom Culture and the Spatial Practice of Possibility in Detroit,” Gender, Place & Culture 21, no. 4 (2014).

Bailey, “Engendering Space.”

A “legend” is the scene’s terminology to describe a category of individuals whose contributions to the scene categories are unique in their execution, numerous, and inspire/influence subsequent competitors. An individual must actively compete for roughly five to seven years before they can be considered a legend. Further, an individual only becomes a legend following a “deeming ceremony,” during which previously confirmed legends deliberate and welcome the new legend. An “icon” refers to an individual whose contributions undeniably influenced subsequent generations of ballroom competitors; individuals included in this category are understood to be part of the ballroom scene’s hall of fame. Both designations are part of LSS (legends, statements, and stars)—the ritualized performance system that Marlon Bailey delineates in Butch Queens Up in Pumps: Gender, Performance, and Ballroom Culture in Detroit.

Hortense J. Spillers, “Mama’s Baby, Papa’s Maybe: An American Grammar Book,” Diacritics 17, no. 2 (1987).

Spillers, “Mama’s Baby, Papa’s Maybe,” emphasis in original.

The following video highlights Yolanda Jourdan’s contributions to the ballroom scene during the height of her storied career: FQ Power Redux, “The 90s IT GIRL: Yolanda Jourdan,” YouTube video, April 7, 2009 →.

Ballroom Throwbacks Television-Brtbtv, “THE LEGENDARY PERFORMANCE DIVA YOLANDA JOURDAN,” YouTube video, April 7, 2009 →.