Leo Felipe’s A História Universal do After (A universal history of the afterparty) can be read in different ways. The book, published in Portuguese (nunc, 2019) and Spanish (Caja Negra, 2022), might be an autoethnographic record of a scientist who loses his sanity as his research progresses. Also, it’s a narcotic chronicle written in the heat of the underground electronic music scene in Porto Alegre, São Paulo, and Belo Horizonte, Brazil. Or it can be read as a compendium of art criticism texts which, instead of analyzing paintings or installations, analyzes parties in demolished warehouses and blocked streets, and the prolonged effects of ketamine or DJ sessions.

Through various first-person textualities (letters, newspaper clippings, poetic notes on the threshold of death by overdose), Felipe examines a recent moment in the Latin American conjuncture: the reconquest of urban space by political identity groups seeking not a promise of happiness, but at least a (dis)organized backwater from the violence of capitalism in the Brazil of the 2010s. Taking a distance from utopian readings of white electronic music, the book proposes a South American materialism of the party in which the universal is reached through the particular stories of those who left everything on the dance floor: Black bodies, trans bodies, and drugged bodies dancing in the ruins of the modern imagination, waiting to be reborn in whatever comes after the end of the party. What follows below is the book’s last chapter.

—Caja Negra Editora

***

X for Bronx

I used to say that even the worst O Bronx party would always be better than the best Base party. Self-criticism is warranted here: more than anyone, I was aware of the formal fascination that the Black body exerts and of the ideological nature of this fascination. Beauty is a political fact, and it is important never to forget that the object of desire is itself a subject. Sue accused me of using the new “cast”—her friends—as part of my scenography. It was a harsh accusation that challenged the party’s politicization discourse.

My high had always been to pay attention to what the new kids were proposing. Why should I act any differently with the most interesting thing that had emerged on the Porto Alegre party scene in the last quarter of a century?1 O Bronx brought Black people to the heart of a scene dominated by whites wishing to be Black. The hipster—the “white negro,” in Norman Mailer’s expression—is the greatest of appropriators.

There is love in São Paulo. Photo: Ivi Maiga Bugrimenko.

In a famous 1957 essay, Mailer (a stereotype of the heterosexual white man: a drunkard, a womanizer, quarrelsome, and a sports fanatic) describes a group of young people in the United States who, despising the materialistic values of the American way of life, turn towards African American culture in search of a reference for their refusal. The hipster is the American existentialist. He rejects Protestant morals underpinned by work and sexual repression and launches into a childish adoration of the present. This is how he manages to live under the shadow of death that was projecting itself over postwar Western society, be it the instant death that could come at any minute with the atomic bomb or the slow death of conformism.

“Hip” means the hip that moves freely to the sound of jazz and also designates what’s new in the scene: that which the most progressive want to know about, the avant-garde, the hype. The meaning of hip is opposed to that of square: uptight. In another essay on the same topic published two years later, Mailer compiled a list (not by chance, the hipster’s favorite literary genre) distinguishing the characteristics of one group from another. While the hip would be wild, romantic, instinctive, spontaneous, nihilistic, perverse, Catholic, a question, endowed with free will, and Black (among other attributes), the square would have the “opposite” qualities: practical, classic, logical, orderly, authoritarian, pious, Protestant, an answer, determinist, and white. Mailer’s list ends up reinforcing some of the racial stereotypes that infect our imagination today. I assume he made it with reference to the generation of young writers that would later be known as the Beat Generation.

Hip also has to do with another concept: cool, detached from the world of passions, the elegant and imperturbable coolness of the nonchalant, of those who couldn’t care less about the opinions of others. Miles Davis is the avatar of cool, blowing sparse notes on his trumpet, facing away from the white audience. What therefore fascinates Mailer’s “white negro,” the high that makes him long for the secret novelty, the hottest thing on the block, is that all this exists in the first place so that he cannot have access. He’s not on the guest list. But that won’t stop him, and he’ll do anything to find out the secret.

Mailer highlights some important elements for the existence of the hipster, signs of marginality appropriated from African American culture: marijuana, jazz, and above all, language full of slang and expressions unintelligible to straight people. The hipster is a practitioner of blackface whose mask is not made of paint, but of words, gestures, and ways of presenting himself, for example through haircuts or clothing.

More than half a century after his birth, the hipster is still fascinated by novelty. The old commodity has been expanded/exploded into what we call lifestyle. To live well, the hipster is not supposed to feel any guilt, and that always requires the best intentions. O Bronx wasn’t about intentions. O Bronx was action. Empowerment from material achievement within the capitalist system, as taught by Beyoncé. O Bronx neither deserved nor needed my condescension. Attention was actually needed, because there were differences—the chasm—of age, race, and class. I had to walk a tightrope, aware of my own steps (read: privileges), the little steps2 (more than being affectionate, the diminutive here is referential), and the GIANT STEPS of everyone involved it making it happen, like Clara, Rhuan, Laura, Golden Girl, Camila, Robson, Lana, Jean, Endriew, Carlinhos, Andrius, Micha, Lua, the Yrenes.

Louïc Koutana a.k.a. L’Homme Statue, Photo: Ivi Maiga Bugrimenko.

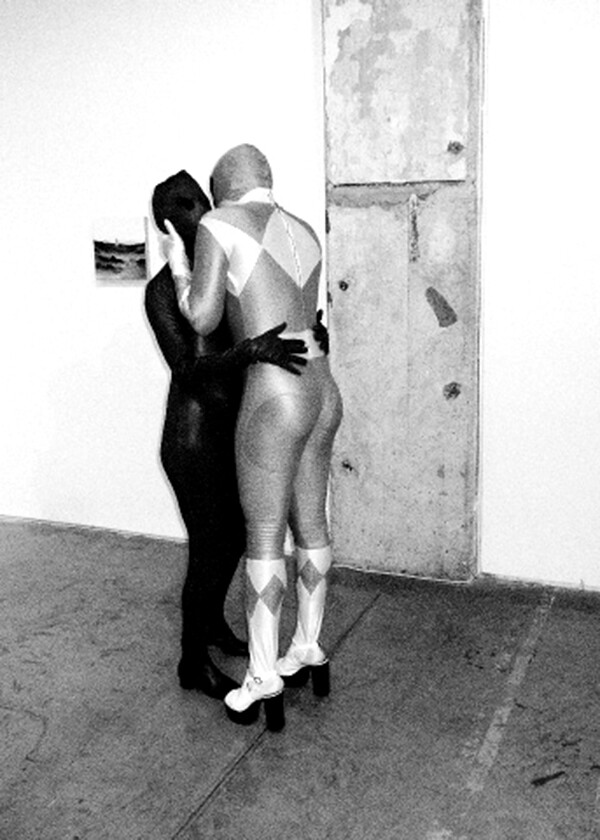

Army of the night. Photo: Ivi Maiga Bugrimenko.

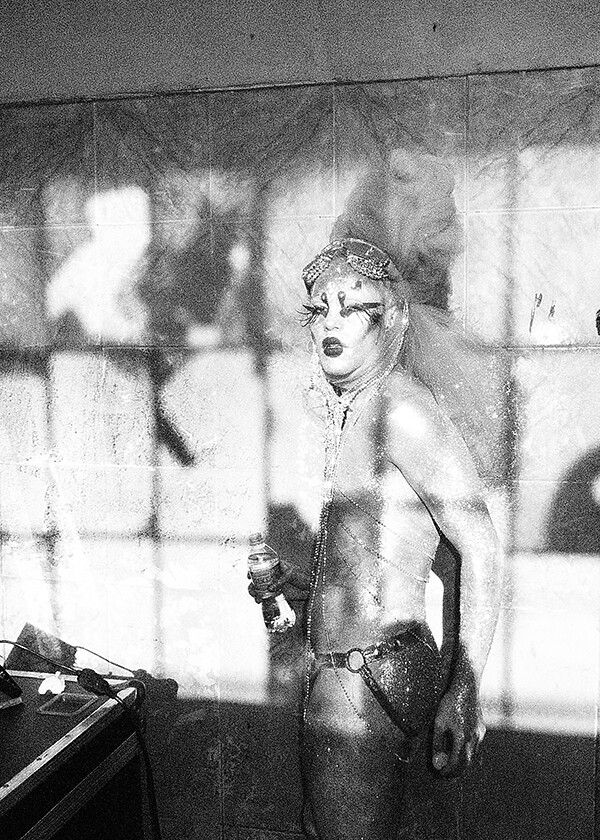

The great Alma Negrot. Photo: Ivi Maiga Bugrimenko.

Louïc Koutana a.k.a. L’Homme Statue, Photo: Ivi Maiga Bugrimenko.

Unlike the hip-hop scene that often reproduced gender phobias, hatreds, and prejudices, O Bronx was an LGBTQ+ party, open to whoever else needed to be included in the acronym. Clara and Rhuan were in their early twenties (or not even there yet) and were learning to produce it by sheer force. Their families were from Restinga, one of the most populous neighborhoods in Porto Alegre, where a large part of the city’s Black population was relocated in the 1960s after being evicted from the region that is now Cidade Baixa. Clara told me that her mother produced Black dances in the 1990s. She, therefore, belonged to a lineage of partygoers. Clara worked as a model and Rhuan had dropped out of architecture school because he hadn’t gotten a scholarship.

By one of those weird coincidences, the owner of the garage where we had parties mistakenly scheduled Base and O Bronx on the same date. We ended up moving to the outdoor parking lot at the other end of the same block. It was a good location, between the bus terminal and a Universal church, with the road network of bridges and overpasses and lampposts and high-voltage wires and billboards announcing the new policed Brazil, meshing with the dark-blue sky and pink clouds of a night of concrete, light, and absurdity. During preparations, Rhuan came over to our location. He asked a few questions about the sound and light equipment. We exchanged phone numbers. A gentle and engaged guy. He was wearing a t-shirt three sizes too big and a pair of basketball shoes that were as white as his t-shirt. I said I would stop by his party later and he replied that I would be on the list.

When I entered the crowded garage, I noticed there were few white people in the place. Everybody danced as if the world would end before the party did. The looks were great, and the crowd, uninhibited, was doing the funk moves known as sarrada. At Base, things still hadn’t picked up—only a few technocrats were moving on the dance floor as if they were still warming up for the big race. Meanwhile, O Bronx was already on fire! The party had started earlier and also ended earlier, and afterward, their whole entourage came to Base. Lively and stylish people who knew how to have fun.

From that day on I started inviting them to our parties. Then I got Sue’s comment. The electronic music scene is generally a mostly white, elitist space. It would not be easy to break with this logic of selectivity. First, there was the issue of infrastructure. Access needed to be facilitated. I thought that part of the public who could afford a more expensive ticket at the door should finance those who couldn’t. The bar also had to operate at affordable prices, but above all, the movement had to come from within, in an organic way, that is: with the presence of Black DJs and performers. Electronic dance floor music (the term was coined by post-structuralist ninja DJ Dr. Malhão to distinguish it from the academic electronic music of concert halls) should be reappropriated by those who had created it. For now, this seemed like a utopia.

I started to advocate for the establishment of something called the techno sarrada as a way of subverting the technocracic zombies’ rigid dance moves. But one night, talking to Duda, I realized that the techno sarrada was also a cultural appropriation on my part. The contradictions we were experiencing manifested themselves in many ways and in many places, including in the hips. We threw an epic afterparty on the one-year anniversary of O Bronx, maybe the last big one in the apartment. Two dozen people huddled on the living room couches talking and dancing, and people were having sex in the bedroom and doing drugs in the bathroom. My funky flat.

Sue ran the whole show. She was a lioness who faked it so completely that she arrived at sincerity. At fifteen she’d gotten a tattoo on the back of her neck with the name of an emo band that consisted of a letter of the alphabet and a number. Sue had other tattoos all over her body: a mermaid on her forearm, an oyster (or was it a vagina?) on her ring finger (she later tattooed a tourmaline stone on top), and the word livre on her belly, which means “free.” When I met her, she lived in a communal feminist house in Cidade Baixa and sold brizadeiros at street parties.3 Then she moved in with her grandparents at a housing project on the other side of town, but went back to Restinga almost every week to visit her mother and two little sisters. She ended up dropping out of college to dedicate herself to DJing and managing Casa Frasca, which she transformed into a space with a more pronounced political character (for example: no-men nights).

Kontronatura at Obra, São Paulo, Brazil, 2022. Photo: Ivi Maiga Bugrimenko.

I used to hear her tell friends that she was in an open relationship. I found it amusing until I realized that I was the open part, not the relationship. My other half is an open book. My party is a broken heart. My sex and drugs don’t have any rock ‘n’ roll. In Rio, I stayed with Lígia and Marília (my wonderful hippie aunt), in Glória. When I read in the news that the PCC had arrived in Favela da Rocinha, days after the military intervention began, I remembered a question that someone had asked at the seminar on drugs I attended at the university.4 What would be the consequence of the war between criminal factions over control of drug trafficking in Brazil? Militarization, the expert had replied. When a faction decides to control the entire drug trade, it will act directly at the borders. The product comes into the country through its geographic borders, which are guarded by the army. I wondered if the two facts—military intervention and PCC’s arrival—had a connection.

It was a Friday morning and I had been struggling to finish the book, and hadn’t left the apartment in a week (I only went out to eat and buy something to drink, except for the time when I walked to Urca with Amanda, after Bruna went back to Porto Alegre). My cell phone buzzed with an incoming message. It was Sue, saying that she had written me a letter. I had nudged the lioness hours earlier with a like on a photo where she looked really beautiful. I was moved. It was the first letter I got, after so many messages. Reading it, I noticed that it looked more like a prose poem than a letter exactly. Sometimes she referred to herself in the third person and this pronominal change also happened in reference to the addressee, which in this case was me. I asked her if I could publish an excerpt in my book. “Feel free.” Then she wanted to know which part I would use. I said all of it, and I immediately worried if that wouldn’t also constitute appropriation. Or was it praise? The letter-poem had the enigmatic tone of Ana C., some vignettes with excerpts from the lyrics of “Ashes to Ashes,” a refrain from Soul II Soul, among other references.5

Once again in the vampire’s alcove

Little fruit bat

After all,

As if you spent too many lines on me

Purple drank don’t make me high anymore

I’m grateful, something easy to digest (poem)

I am happy hope you’re happy too

Our love is crush revival, not at all romantic

It was the first time I felt afraid of you. I was happy, something new in the middle of a lot of nothings reminded me.

—Where are you? —afterafter

So pretty it’s a waste

Her getting ready is like a bride, just cooler and nonmonogamous

—I don’t think so

He wasn’t him, she wanted romance

—Pure disguise. It was more like debauchery, but I didn’t know how to show it.

And there goes my cheap cognac.

There was another time (and another) that I painted a monster in the features of your face.

It was a sketch. I threw the sheet away and found you so sweet.

I didn’t mean to cause any trouble, I swear. My mother always told me that I am all over the place. Daughter of Iansã, a whirlwind, lucky.6

I was sure I knew how to hide—but he read me. What she thought he should read, he didn’t. Between discourse, long texts, and theory, he wrote me what he thought it was.

Not even she knew.

There was another time when I was scared too. I ran off like a skittish kitten. And the dance floor was hot tin. On purpose. I was hurt and wanted to make a noise, the little lion that she was.

My momma said to get things done

A time on the other side of the abyss (back 2 life, back to reality). She comes back running with her tail between her legs, asking for a cuddle. This time more daring. Pretending not to be, but excited by the timbre of your ego and the little precious stones. If only I had the assurance of a well-established whiteman. At least what he appears to have.

A few minutes later, another message arrived:

It’s not supposed to be a story, or a joke, or a hey there, long time no see, or an apology. It’s more like a collection of those vague phrases that would only be understood between us. I could include other moments, but you know how my head is always full, I forget.

Porto Alegre is the capital city of the southern Brazilian state of Rio Grande do Sul. According to the 2010 census, nearly 80 percent of the city’s population identified as white. —Eds.

In Portuguese, “passinhos.” Passinho is an urban dance style that emerged in the favelas of Rio de Janeiro.

Brizadeiro is a candy made of chocolate, condensed milk, and weed.

The PCC (Primeiro Comando da Capital, or Capital’s First Commando) is one of the largest criminal organizations in Brazil. With operations mainly in the state of São Paulo, the faction is also present in almost all Brazilian states, in addition to neighboring countries. The military intervention refers to the federal intervention in Rio de Janeiro in 2018, imposed by the then-president of Brazil, Michel Temer, who ordered the national army to assume the role of the police forces in that state.

“Ana C.” refers to the late Brazilian poet Ana Cristina Cesar.

Iansã is an orisha, or deity, worshiped in Afro-Brazilian religions.

Category

Subject

Translated from the Portuguese by Patricia Davanzzo.

This excerpt appears courtesy of the author as well as nunc edicões de artista and Caja Negra Editora.

All photographs are copyright of Ivi Maiga Bugrimenko.