Hegemony, which can be thought of as either “common sense” or the dominant way of thinking in a particular time and place, can never be total, Williams argued, there must always be an inner dynamic by means of which new formations of thought emerge. Structure of feeling refers to the different ways of thinking vying to emerge at any one time in history.

—Alan O’ Connor, Raymond Williams: Writing, Culture, PoliticsThe only good system is a sound system.

—Jamaican ProverbTurn this bitch into gay pride the first one was a riot.

Stonewall 2022, fuck it homophobes dyin.

—Dualité

I’m in Jamaica reflecting on what the hell Hood Rave is about and wrestling with how to put my ideas about structuring a femme space onto paper. I am hesitant to write some kind of manifesto where I present an idyllic vision of what Hood Rave is, as if it’s a perfect space. It is not that at all. But it is a vital and necessary space. Hood Rave is an experiment in creating a Black femme and Black queer underground community. Note that the terms “Black femme” and “Black queer” are not mutually exclusive, and I’m wrestling with language. This writing is an attempt at writing alongside a live, unfolding experience of underground Black culture. The live space will always exceed the bounds of this writing. Hood Rave is a collective conjuring of ecstatic energy. It is a ritual for togetherness, actively making and reshaping what it means to be in Black community. Culture happens in real time, consciously and unconsciously performing and expanding the social repertoires of the past. This writing is meant to be an accompaniment to the live event.

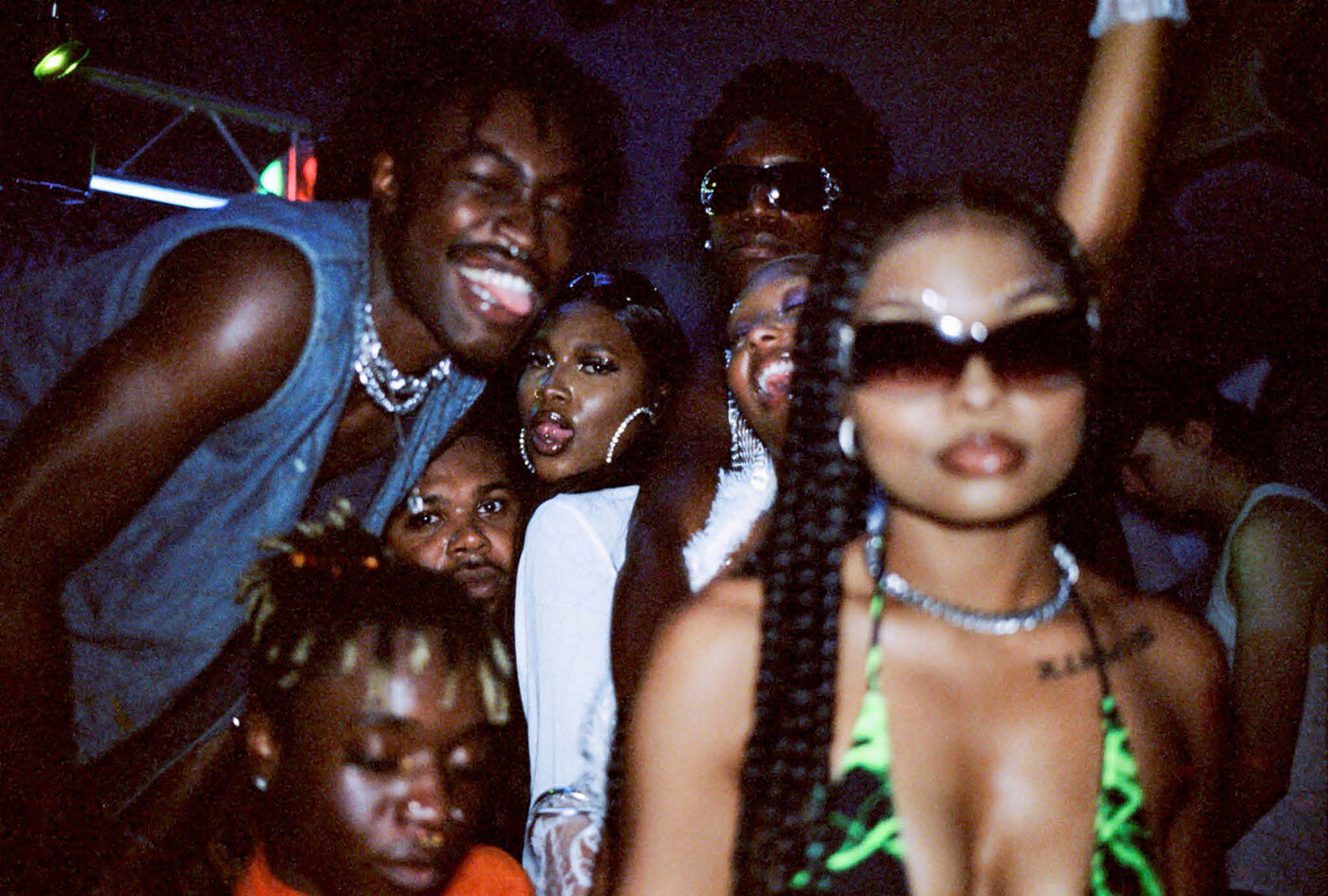

Photo: Sam Lee

The event takes place at the margins of institutions in Los Angeles: after closing time, extralegal, in back alleys. I used my time and funding as a doctoral student to learn how to DJ and started throwing parties back in 2016. Academia was a scaffold to do what I wanted to do outside of its walls, the rave’s condition of possibility. As a Black femme and queer person, I found most institutions stifling, whether the university or the nightclub. In LA, Black folks were excluded from many nightclubs via veiled racially coded entry policies (“No baggy attire,” “No sportswear,” “No sneakers”). Within Black spaces, a heteronormative gaze made it impossible to dance freely with my girls without having a man grab me inappropriately or try and force me to engage with him. Just by being in their bodies, the Black femme queer bumps up against hegemony, often experiencing harm in the process. We become stultified by sexual harassment, anti-Black microaggressions, and the expectation to emotionally labor for others. What would it be like to create an intramural space for us where we were at the center, maintaining our energy to nurture ourselves?

At the initial above-ground parties I threw at conventional bars and clubs, I had to deal with stifling restrictions. Just last week my best friend and collaborator DJ Kita and I threw a party at a club in LA as a trial for taking our events back above ground. We experienced racial microaggressions from the security staff, who prevented our crew from setting up before our event opened to the public. They threatened to shut down our party if the caterer dared to play “loud music” (read: rap music) while loading in the food. Venue security in LA has been known to be particularly aggressive against Black femmes, with pointed hostility towards Black trans and nonbinary folks. Heteronormative standards are imposed, such as the security team physically patting down folks they perceive as “males,” but not those they identify as “women.” Unfortunately, most clubs and bars in LA are currently owned by wealthy straight white men.1 The privatization and white ownership of gathering places, along with racist gang injunctions and the de facto prohibition of large groups of Black folks gathering together, have eroded Black community. To get the force of white heteronormativity off our necks, we came to the conclusion that we have to return to the underground.

Defining the Space

Hood Rave is an attempt by two Black femmes, myself (BAE BAE) and DJ Kita, to create space for our overlapping communities to share physical space. I think a lot about the assertion I heard from Saidiya Hartman during a talk at UCLA that Blackness has always been queer.

I identify as queer, but Kita does not. Kita and I are both from South Central LA, but our paths are distinct. I’m thirty-seven, ten years older than her, so I feel like her big sis (also because tbh I’m a nag). We both come from working-class families. I went the route of pursuing grad school to get out of my family’s socioeconomic prison and ended up with mountains of debt thanks to the price tag on my BFA in film from UCLA and MFA in film from Columbia University. Kita didn’t finish her undergraduate studies at UC Irvine and eventually found her passions in DJing. She is one of my favorite DJs and has an encyclopedic knowledge of a wide range of rap and hip-hop music.

Becoming a DJ was a line of flight for me away from filmmaking—a place where I had the possibility to invent my own path. White and Black male gatekeepers in the film industry and academia could not stifle me. As a DJ I learned about all sorts of dance music genres and created an eclectic approach to mixing many kinds of Black diasporic music, including house, jungle, techno, footwork, baile funk, batida, and a lot more. Hood Rave was the perfect combination of Kita’s and my approach to music: mixing popular and independent “hood” music with Black rave music to create an open-format dance party. The name “Hood Rave” is a major draw because people get the sonic and fashion aesthetic instantly. Black and brown people have been raving in the hood for generations, from the warehouse parties in Chicago to Freaknik in the nineties. Hood Rave is about living out our Black queer collective fantasies.

Friendsgiving. Photo: Alex Free.

Hood Rave is an ephemeral architecture, a structure of feeling that emerges in the gaps of institutional space, after hours, in darkened space. It plays off certain physical structures and technologies, including the sound system, colored lights, warehouse architecture, and open outdoor space, and uses them to create something that actively pivots away from white patriarchal hegemony. It is a space for Black queer people and femmes to play. As much as afro-pessimism might negate it, Black intramurality is real, salient, and productive of new realities. Collective Black culture saves lives. Strangely, the dominant culture that exists is a culture of individualization, separation, and confinement. How do we go back to the collective cultures of our ancestors and renew it through a queer, feminized interpretation of life?

There is no road map, but that is our purpose.

The Hood Rave project is not about being reactive to heteronormative culture, or becoming its inverse. It is instead about centering Black femmes and affirming their right to exist. I think about Sylvia Wynter writing on the centering of the white liberal man in modern notions of what it means to be “human.” She urges us to instead think of what it might mean to center the person on the margins. For us, this means centering the Black femme and the Black queer especially. What makes her feel safe? How does she want to dress? How does she want to act? What is her musical taste? This is a kind of praxis where folks who attend the party actively answer these guiding questions. I am constantly learning about their needs and attempting to reorganize a space to attend to them.

Having Kita and me at the helm and on the microphone hosting makes a big difference in how Black femmes feel when they attend. We state the rules on the mic at the height of each party: “This is a Black femme–led space. This is a consent-centered space. Transphobia and homophobia are not acceptable here.” We explain to people that you cannot touch anyone without their expressed consent. At every event we have a harm-reduction table run by the collective Rave Safe, which distributes Narcan kits and fentanyl strips for folks to party safely. Along with this we hire safety monitors who help to observe the partiers throughout the night. They are points of contact if people experience harm or need support. I know from past experiences in aboveground clubs and bars what it feels like to not know if someone is going to touch me without my consent, and how unsafe it feels to let loose while being gawked at. At Hood Rave, Black femmes are the actors, not passive objects. It is not surprising to find that most of our DJ and performer lineups are composed of Black femmes and queers. It’s our normal.

In Hortense Spillers’s essay “The Idea of Black Culture” she writes: “It is striking that precisely because black cultures arose in the world of normative violence, coercive labor, and the virtually absolute crush of the everyday struggle for existence, its subjects could imagine, could dare to imagine, a world beyond the coercive technologies of their daily bread.”2 Hood Rave is about forcefully taking up physical and sonic space with our imaginations. It is an act of collectively refusing the world and making new realities. Our space argues that we can constitute new material and imaginative realities, even if it’s for six hours in the middle of the night.

Hood Rave Halloween. Photo: Taylor Washington.

Hood Rave Halloween. Photo: Taylor Washington.

Hood Rave Halloween. Photo: Taylor Washington.

Hood Rave Halloween. Photo: Taylor Washington.

But Spillers warns at the end of her essay that Black culture can be co-opted when it becomes taken up by “Americanization” and hegemonic culture. She writes: “Perhaps black culture—as the reclamation of the critical edge, as one of those vantages from which it might be spied, and no longer predicated on ‘race’—has yet to come.”3 What I propose is that this “critical edge” can be found at the margins of Blackness that Black femme, Black queer, Black poor, and Black working-class folks inhabit. These are the actors that make Hood Rave what it is. As Dualité, a recent Hood Rave femme queen performer, raps: “Stonewall 2022, fuck it homophobes dyin.” We seek to embrace the power for the imaginations that exist at the margins of the so-called human, and magnetize each other to the point of creating community in a world that wants us dead. Fuck the world, Hood Rave is our shit.

I have undoubtedly by now fallen into the kind of idealized manifesto-writing I warned against early on in this essay. A girl can dream …

Sadly, this includes the club Jewel’s Catch One, the formerly Black-lesbian-owned gay and lesbian staple in Mid-City, LA.

Hortense Spillers, “The Idea of Black Culture,” CR: The New Centennial Review 6, no. 3 (Winter 2006): 25.

Spillers, “The Idea of Black Culture,” 26.