10,000 Screaming Faggots

“10,000 Screaming Faggots (Hood By Air FW14)” was the title of the musical score for the fall/winter 2014 Hood By Air (HBA) fashion show, with contributious from DJ Total Freedom, Tim DeWitt, and Juliana Huxtable.1

The theme for this show was trans as the future-forward prefix to the raw creative adaptability of streetwear fashion.2 HBA cofounder and CEO Leilah Weintraub explained that one of the show’s goals was to elicit emotional responses to the fashion line’s incubation of ideas rather than one particular theme.3 And true to his description, much of the show’s designs were androgynous, as models of all genders were adorned with halos of hair extensions, loose-fitting silhouettes, skirts, and heeled boots. The collection featured many staples of streetwear fashion such as graphic T-shirts, jackets, and sweatpants punctuated with metallic adornments and decorative zippers, and accompanied by strappy platform boots often seen in underground cyberpunk/goth music scenes. The show itself was minimalist, almost mimicking showboating walks down hallways into dark clubs, with flashing white lights complimenting the rhythmic bass of the soundtrack.

Shayne Oliver, HBA cofounder and designer, insists on a multi-sensorial experience on the runway, which draws from his experience as a DJ at New York City’s influential GHE20G0TH1K party, which was established by longtime friend Venus X. The party sought to unite the Black, queer, and goth party scenes she frequented. In an article titled “Court Catharsis Through Chaos,” Nico Amarca describes this influential party in these terms:

Face tattoos, Buffalo platforms, chokers, bondage trousers, Marilyn Manson T-shirts, lime green braids, blinged-out gold name chains and head-to-toe Hood By Air. You walk inside to a scene reigned by chaos and mutability. Dark rap, Jersey club, ballroom, industrial, nu-metal, dancehall, grime, reggaeton, baile funk and Aaliyah all rammed into each other at frenetic cadence. Vogueing, shuffling, dabbing, twerking. Welcome to GHE20G0TH1K.4

Shayne Oliver with model Unia Pakhomova in 2021. License: CC BY-SA 4.0.

In the formative years of GHE20G0TH1K, Oliver was resident DJ, which allowed both HBA and GHE20G0TH1K to grow alongside one another.5 As a result of their shared “dark banjee aesthetic,” Oliver and Venus X collaborated on several projects.6 GHE20G0TH1K became one of the most electrifying creative centers for queer people of color in the US. Venus X often collaborated with underground queer electronic dance music artists, DJs, and labels, such as DJ Total Freedom and LA-based label Fade to Mind.7

Although DJ Total Freedom met Oliver through the GHE20G0TH1K network, he developed his career through LA-based parties. Formerly and briefly (mis)named the “worst” DJ, Total Freedom found his groove two years before connecting with Venus X, by playing at Ignacio “Nacho” Nava’s Mustache Monday party and at the Wildness party he cofounded with friends Wu Tsang, Asma Maroof, and Daniel Pineda.8 Total Freedom says his method of music-making is heavily influenced by Venus X and Oliver’s “disruptive” and “uncomfortable” style.9 Venus X’s dynamic GHE20G0TH1K sets were considered “deconstructed” or “post-”club music.10 As a DJ, Venus X juxtaposes, blends, and remixes her queer, Afrodiasporic, and women/femme identities, explaining in interviews that the deconstructed music coming out of Ghe20 G0th1k was influenced, in part, by the recession that began in 2008, the cultural obsession with the apocalypse leading up to 2012, and young adults’ resulting feelings of anxiety and helplessness.11 Sonically, “post-”club music is a genre characterized by a “post-modern” blend that

breaks away from dance music tropes like four-on-the-floor beats, stable tempo, and constant mix with gleeful anarchy, proposing a sonic locus where ballroom breaks, field recordings, rap a capellas, and heavy metal are reconfigured into dancefloor fodder … It’s vision is high- and low-brow cultural signifiers in order to reclaim the club floor co-opted by mainstream electro-pop and EDM.12

The “post-”club music style became a disruptive force in electronic dance music by breaking away from the conventions of Top 40 club remixes made popular in the 1980s and ’90s. In the “post-”club music ethos, difference is incorporated into the mix to seemingly address how nightlife became splintered across music genre, race, ethnicity, and sexualities in the late 2000s and early 2010s.

***

I’ll return to HBA’s use of “10,000 Screaming Faggots (Hood By Air FW14)” shortly, but first, some considerations on Black sound and the DJ set. Kodwo Eshun’s More Brilliant Than the Sun illustrates how writers can study contemporary Black music and its electronic afterlives after soul without the identity politics of “the street.” Such a call tantalizes scholars of alternative Black music who contend with genre redlining by music industries and the artists this marginalizes.

Black feminist traditions of both humanist and post-humanist camps highlight how white supremacy undergirds the (post-)Enlightenment concepts of human and post-human,13 which allow mainstream music industries, festival/event planners, and enthusiasts to adopt race-blind attitudes—such as PLUR (Peace Love Unity Respect)—that maintain the status quo of this nearly seven-billion-dollar global music industry economy.

The Make Techno Black Again hat was released in 2018 and 2020 by HECHA/做, Grit Creative, and Speaker Music.

Artists of color in electronic dance music—especially queer artists of color—have developed a musical epistemology that references the sonic archives of Black queer life to prioritize coming together in difference within DJ mixsets. How can these “Afro-philo-sonic fictions” help us work through the tensions of our lived material realities to relate to one another and even achieve unity?14 This is especially urgent given how decades of marketing by the mainstream music industry has decentered the racial/sexual minority liberatory politics of EDM culture while adopting almost all of its production styles. These (re)discoveries are timely given the recent calls to democratize and even return the rave to the queer Black and brown communities from which it emerged.15

DJ sets are sonic journeys, fictions—or as DJ scholar Paul Miller (DJ Spooky) explains, “mood sculptures … generated by the assembly process of DJing and sequencing etc. the social construction of memory.”16 Through mixsets, queer-of-color DJs reconstruct minoritarian life through the sonic archive by sampling and remixing. Here, Lynnée Denise’s notion of “DJ scholarship” connects the DJ as song selector to DJ as archivist.17 Queer DJs of color use sets to signify their connection to contemporary sociocultural identities through sampling the sonic archive of their communities. What is at stake for the inclusion of mixset analysis is paying attention to the lower frequencies of Black and Black queer memory and, by extension, archival practice, which operates “independently … in popular culture and academic historiography.”18 Mixsets of queer-of-color dance music scenes may help to address the limitations of grand narratives and even expand how we archive minoritarian communities.19

The flow of mixsets often mirrors literary form. For DJ, teacher, and theorist Brent Silby, a mixset typically follows a structure similar to fictional storytelling in that it includes (1) an introduction, (2) development, and (3) a resolution.20 We can refer to these as Act I, Act II, and Act III. Act II is the midpoint where DJs find their groove or “main argument” through tracks fitting a chosen theme or mood. During this section, DJs typically introduce conflict characterized by “a slightly different (perhaps harder) sound,” creating the tension necessary to propel the set to the next sound.21 This movement is accomplished through sampling aspects from the introductory section (Act I). The resolution section (Act III) returns to the music style found at the end of the introduction and the beginning of the development section. DJs across minority communities, such as DJs Venus X and Total Freedom, use sets to force listeners into an “active participation” that prevents a “cool and distant acceptance of data.”22 The object is not necessarily to escape reality but to confront pressing social issues by sampling current events.23

***

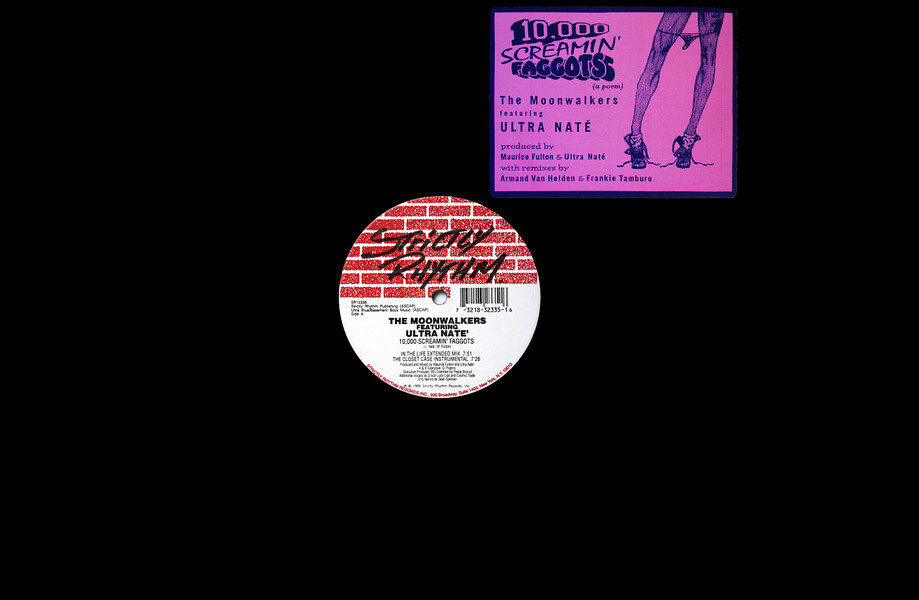

“10,000 Screaming Faggots (Hood By Air FW14)” borrowed its name from the nineties dance track “10,000 Screamin’ Faggots (In the Life Extended Mix)” by The Moonwalkers, a duo consisting of dance music singer-songwriter Ultra Naté and dance music producer Maurice Fulton. According to the liner notes to the Moonwalkers track, it was inspired by a night out in Miami and was (controversially) dedicated to the duo’s gay fan base for their “endless support.”24 There are two main voices in the song. The first is from the perspective of a figure who proclaims his disgust with the exuberant queer clientele in a dance club, and whose own orientation is undiscernible: “They were laughing and dancing / I mean screaming all over the place / Writhing their bodies in total abandon / I mean it was disguting!”

The other voice, which is more prominent, is a female narrator who recounts a dream about performing for an adoring gay crowd:

I had a dream last night

That I was adored beyond imagine

Carried on the shoulders of 10,000 screaming faggots

[…]

10,000 screaming faggots in unison and chaos as they sang

Songs of love and sadness

Songs of honesty and pain

[…]

They were my friends

For to them, I am real

Enjoying the beauty of womanhood

For me allowing them to feel

The female speaker’s call and response with the adoring crowd reifies her gender as she connects with them through emotions of “love and sadness … honesty and pain.” The song is essential to the canon of “bitch tracks” from the queer Afro-Latinx ballroom dance culture of the nineties.25

Total Freedom and Shayne Oliver align themselves with the queer-of-color archival practice of using music to document their history, culture, and aesthetics.26 The musical score to the HBA fashion show mirrors the relationship between the two voices in the Moonwalkers track—the disgusted down-low figure and the woman who is reified by the adoring gay crowd. The mix fabulates how the down-low figure might have met the narrating woman, who, as we will see, is more than the man bargains for.

T-shirt design for Make Techno Black Again by Detroit artist Abdul Qadim Haqq.

Act I: “Let Me Take You Away From Here”

Given the trans theme of the 2014 HBA fashion show, it’s no surprise that introductory section of its musical score deals with disclosure, visibility, and utopia/dystopia. As if mirroring the awe-inspiring night that led to the Moonwalkers dance track, the set starts with a simple but chilling interpellation, or hailing, of the down-low figure: “Do I know you from somewhere?” Does the narrating woman recognize the down-low figure from a night of “laughing, dancing, and screaming all over the place,” with queer bodies “ripping in total abandon”?27

Total Freedom turns the down-low figure on its head by placing the onus back on this figure—for why would he be in a club with a community that disgusts him? The repeating question (“Do I know you from somewhere?”) builds the down-low figure’s anxiety about being misidentified as queer—an anxiety commonly found within Black music and musical critique, such as in Gil Scott Heron’s “The Subject Was Faggots” and the work of Amiri Baraka. Here, the ominous exchange between the “down-low” and the “out” woman who recognizes him points to the strategies of negotiating multiple forms of stigmatized sexual identifications.28 The unease of this interrogation is furthered as the set fades into a sample of a snarling chihuahua over the background of dark industrial otherworldly sounds—as if triggering the return of a repressed memory.

The music, though still ominous, becomes lighter, as if the repressed memory grows more apparent. The listener is placed back into the present moment. Here, the looped a capella of Beyoncé’s “End of Time” fades in. The female narrator beckons to the figure: “Come take my hand / I won’t let you go / I’ll be your friend / I’ll love you so deeply / […] I will love you ‘til the end of time.” The reverbed a capella juxtaposed with the sweetness of the lyrics and the expansiveness of the background music make the narrator seem like a siren calling the listener to a forbidden fantasy just beyond reach. “Come take my hand” repeats as dissonant strings and space sounds fade in and eventually crescendo over the vocal sample. The chorus continues: “Let me take you away from here / There’s nothing between us but space and time / […] Let me shine in your world / […] Make me your girl.” The phrase “Make me your girl” repeats as if signaling the completion of a spell entrancing the figure. Here the sampled lyrics have a foreboding tone that overloads surface, or first impression, in order to obscure an esoteric meaning that is available only to those who are knowledgeable of alternative networks and systems of meaning.

Act II: “No I’m Not the Girl You Thought You Wanted”

The mix then changes moods to introduce the conflict. This begins with the fading-in of a spoken word piece by DJ, visual artist, and writer Juliana Huxtable: “When small boobs are championed by the defeat of the social impulse to make them bigger and more supple by the same sleazy dudes in the Upper West Side with pec implants whose parents secretly orchestrated the creation of distinct gender dysmorphia from the … ”

The placement of this piece introduces the down-low figure to the alternative epistemes hinted at by the vocoded Beyoncé sample. As if calling for a new world order, Huxtable’s renouncing of antiquated beauty standards and gender norms juxtaposed with the space sound effects and lyrics discloses the woman speaking as alien to the world of the down-low figure. The woman is “eccentric”29 because she satirizes and critiques the heteronormative regimes in which they both live. She positions herself as not an alien, but someone who transcends these regimes. The lyrics “space and time” simultaneously evoke the “tensed” and “tenseless”-ness of the Black performance aesthetic found between Beyoncé’s lyrics and Huxtable’s spoken word piece. As Huxtable’s piece trails off, her words are garbled, as if suggesting that her words and perspectives are inhuman or illegible to the systems that seek to “code out” the lower frequencies of alternative epistemologies.30

That the woman is more than she appears is highlighted by a sample from the horrorcore classic “Load My Clip” (1995) by Lil Noid. While the chopped and screwed sample is brief, it fits the generally dark apocalyptic (read: beginning-of-a-new-era) theme and genre of the set.31 The lyrics further reveal that the speaking woman has a strong sense of self:

Talking shit I’ll load my clip and shoot you in your fucking face

Bring that shit up to the door you wanna try me, Noid hoe

[…]

Bitch my nuts you best not ever test

Blackout is my nigga so Lil Stabby got his fucking back

Get yo’ hands up we’re the ones so damn near we gon have to scrap.

This passage suggests that the narrating woman is not only willing and ready to defend herself but also has the support of her family. This is punctuated by a chorus of barking chihuahuas, a longstanding effeminate signifier for gay men.32 Interestingly, the sample placement can be read as both an affirmation of ethnic identity and as self-defense. The African-American Vernacular English within this sample, as a means to iterate a strong sense of Black identity, is reminiscent of the saying “My gender is Black.”33

This saying attends to how the traumatic events of the transatlantic slave trade excluded African descendants from the binaries of public/domestic gender roles.34 The violent imagery of the lyrics is reminiscent of the “by any means” self-determination helpful to women, femmes, and nonbinary people of color living in defense of themselves, as outlined by the Black Panther Party and the Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries (STAR).35 Such a call for self-defense is especially poignant given the simultaneous under- and over-enforcement in Black transgender and queer femme communities. The sample of “Load My Clip,” appearing in the “conflict” section of the mix, serves as a recognition of the phantom of violence (state or interpersonal) that haunts transwomen and queer femmes.

Act II continues into an industrial interlude featuring a chopped and screwed remix of Beyoncé’s “No Angel.” This is not only a nod to Houston’s Black music scene; by slowing down Beyoncé’s voice and lowering its pitch, the sample also troubles notions of gender classification and humanity: “Baby put your arms around me / Tell me I’m the problem / No I’m not the girl you thought you wanted.” The song nods to the politics of gender disclosure, passing, and visibility within the transgender community.

The vocoded vocals and the lyrics also touch upon how Black performers use technology to invent what it means to be human. As the Beyoncé sample continues, the narrator reveals herself to the figure: “Underneath the pretty face is something complicated / I come with a side of trouble / But I know that’s why you’re staying / Because you’re no angel either baby.” If the previous section and the beginning of Act II set up the antagonistic relationship between the down-low figure and the female narrator, whose trans dispositions are gradually revealed throughout the set, then this section, with its exaggerated vocoded vocals and lyrics, is the climax or resolution. It signifies a leveling of the field, which is needed for the down-low or closeted figure to open himself up to the world and worldview in which the narrating woman exists.

Act III: Cunty

Now that the world has opened for the down-low figure, the mix’s dénouement explores themes of liberation, belonging, and self-affirmation. This is accomplished by the quick fade-in and loop of Disco Lucy Lips, the narrating woman in the original Moonwalkers song, shrilly yelling “10,000 Screaming Faggots.” At the same time, Total Freedom stacks the sample of snarling chihuahuas in the foreground. The narrating woman of the set interpolates her community and summons her family.

This is especially poignant as the mix moves into ballroom culture’s sound, aesthetic, and history. As the Moonwalkers track fades in, a sample from Kevin Aviance’s “Cunty” enters the sonic landscape, bouncing from left to right in the stereo field. The inclusion of ballroom music acts as a sonic claim to space, moving ballroom from the margins to the center. It also signals an expansion of gender aesthetics. In his analysis of gender in the ballroom scene, Marlon Bailey explains that “cunt,” “pussy,” “feminine,” etc. serve as a criteria for gender performance in competitions and for passing as “authentic femininity” in the real world.36 As the mix continues, trilling and commentating by Kevin Movado Prodigy fills all parts of the stereo field until it crescendos with a double bass drum solo.

The solo fades out into white noise, exaggerating the abruptness of the instrumentalized “ha crash” sound that is characteristic of ballroom dance music. The set then goes into a commentary-vs.-commentator ballroom track, visually marked in the fashion show with a vogue femme performance. What I find poignant in the inclusion of this vogue femme performance by actual dancers is that it visually positions the narrator as a part of a family (house) and the larger community. Whereas queer aesthetics were implicit earlier in the mix, the dancers’ presence in the fashion show makes an explicit claim to Black queer culture and identity. Musically, this is significant given that the “ha crash,” and the Jersey club music rhythmic motif in contemporary iterations of ballroom music, are popular in “deconstructed/post-”club music.

***

Using DJ scholarship, I’ve attempted to excavate the sonic archives within “10,000 Screaming Faggots (Hood By Air FW14)” to illustrate the way electronic dance music DJs aurally represent the culture, issues, and experiences of Black queer communities. Mixsets can be viewed as archival objects that contain culturally specific histories, epistemologies, and ontologies important to underrepresented communities. Harking back to Tricia Rose’s discussion of electronic dance music, I hope future scholars and critics place electronic dance music back in the Black radical tradition.37

You can listen to the score on Soundcloud →.

SHOWstudio, “Hood By Air: Trans - Process Film,” YouTube video, March 21, 2014 →.

SHOWstudio, “Hood By Air: Trans - Interview: Shayne Oliver,” YouTube video, February 7, 2014 →.

Nico Amarca, “Ghe20G0th1k: Courting Catharsis Through Chaos,” Highsnobiety, no. 14 (2017) →.

Layla Halabian, “Venus X on the Origins of GHE20G0TH1K, a Club Night that Shaped the 2010s,” Dazed Digital, December 17, 2019 →.

Eric Shorey, “Hood By Air Is Going on Hiatus,” Nylon, April 6, 2017 →.

Claire Mouchemore and Juule Kay, “How Electronic Artists Influenced Fashion Soundtracking,” Resident Advisor, February 28, 2022 →.

Stone, “Gen F: Total Freedom.”

Kembrew McLeod, “Genres, Subgenres, Sub-subgenres and More: Musical and Social Differentiation within Electronic/Dance Music Communities, Journal of Popular Music Studies 13, no. 1 (2001). Though opinions vary about why the label “deconstructed” is nonsensical, the main contentions are that (1) “deconstructed” is a redundant term to describe the overall form and production style prevalent in club music and electronic dance music more generally, and (2) the term was established by the music industry, in particular music journalists.

Max Pearl, “The Art of DJing: Venus X,” Resident Advisor, April 20, 2017 →.

Andra Nikolayi, “The Radical Dissonance of Deconstructed, or ‘Post-Club,’ Music,” Bandcamp Daily, July 9, 2019 →.

See Sylvia Wynter, “Unsettling the Coloniality of Being/Power/Truth/Freedom: Towards the Human, After Man, its Overrepresentation—An Argument,” CR: The New Centennial Review 3, no. 3 (2003); S. Wynter and Katherine McKittrick, “Unparalleled Catastrophe for Our Species? Or, to Give Humanness a Different Future: Conversations,” in Sylvia Wynter: On Being Human as Praxis, ed. K. McKittrick (Duke University Press, 2015); K. McKittrick, Demonic Grounds: Black Women and the Cartographies of Struggle (University of Minnesota Press, 2006); and Alexander Weheliye, Habeas Viscus: Racializing Assemblages, Biopolitics, and Black Feminist Theories of the Human (Duke University Press, 2014).

Tavia Nyong’o, “Afro-philo-sonic Fictions: Black Sound Studies After the Millennium,” Small Axe 18, no. 2 (2014).

Paul Miller, “Algorithms: Erasures and the Art of Memory,” in Audio Culture: Readings in Modern Music, ed. Christoph Cox and Daniel Warner, rev. ed. (Bloomsbury Academic, 2017), 472.

Chandra Frank, “Listening to the Unsung and the Quiet Imagination: A Conversation with DJ Lynnée Denise,” Journal of Popular Music Studies 32, no. 4 (2020).

Michael Hanchard, “Black Memory Versus State Memory: Notes Toward a Method,” Small Axe 12, no. 2 (2008), 54.

madison moore, “DARK ROOM: Sleaze and the Queer Archive,” Contemporary Theatre Review 31, no. 1–2 (2021).

Brent Silby, “The Structure of a DJ Mixset: Taking Your Audience on a Purposeful Journey,” def-logic.com, 2007 →.

Silby, “The Structure of a DJ Mixset.”

Toni Morrison, “Memory, Creation, and Writing,” Thought: Fordham University Quarterly 59, no. 4 (1984): 387.

See →.

Michelle Lhooq, “20 Tracks That Defined the Sound of Ballroom, New York’s Fiercest Queer Subculture,” Vulture, July 24, 2018 →.

Matthew Collin, Rave On: Global Adventures in Electronic Dance Music (Serpent’s Tail, 2018), 324.

The Moonwalkers, “10,000 Screaming Faggots (In the Life Extended Mix).”

C. Riley Snorton, Nobody Is Supposed to Know: Black Sexuality on the Down Low (University of Minnesota Press, 2014), 6.

I use “eccentric” queerly to acknowledge how Black musicians and performers adopt “appropriation, pastiche, sampling, and irony” to satirize, critique, and reinvent heteronormative Black radical traditions of world-making and self-fashioning. Francesca T. Royster, Sounding Like a No-No: Queer Sounds and Eccentric Acts in the Post-soul Era (University of Michigan Press, 2013), 8. See also madison moore, Fabulous: The Rise of the Beautiful Eccentric (Yale University Press, 2018).

Robin James, “Sonic Cyberfeminisms, Perceptual Coding and Phonographic Compression,” Feminist Review 127, no. 1 (2021): 22.

For an account for the Memphis rap scene that incubated Lil Noid, see Julia, “Underground & Infamous: Part I,” Future Audio Workshop, 2019 →. Julia writes: “At the end of the ’80s, young people were tired of the upbeat electro-funk tunes that had defined the decade so far. The music of their parents’ generation was out of sync with the reality in Memphis.”

Julee Tate, “From Girly Men to Manly Men: The Evolving Representation of Male Homosexuality in Twenty-First Century Telenovelas,” Studies in Latin American Popular Culture, no. 29 (2011): 106.

Hari Ziyad, “My Gender Is Black,” Afropunk.com, July 12, 2017 →.

Hortense Spillers, “Mama’s Baby, Papa’s Maybe: An American Grammar Book,” Diatrics 17, no. 2 (1987): 72.

Jared Leighton, “‘All of Us Are Unapprehended Felons’: Gay Liberation, the Black Panther Party, and Intercommunal Efforts Against Police Brutality in the Bay Area,” Journal of Social History 52, no. 3 (2019), 22.

Marlon Bailey, “Gender/Racial Realness: Theorizing the Gender System in Ballroom Culture,” Feminist Studies 37, no. 2 (2011), 382.

Tricia Rose, Black Noise: Rap Music and Black Culture in Contemporary America (Wesleyan, 1994), 83.