Artists of color in electronic dance music—especially queer artists of color—have developed a musical epistemology that references the sonic archives of Black queer life to prioritize coming together in difference within DJ mixsets. How can these “Afro-philo-sonic fictions” help us work through the tensions of our lived material realities to relate to one another and even achieve unity? This is especially urgent given how decades of marketing by the mainstream music industry has decentered the racial/sexual minority liberatory politics of EDM culture while adopting almost all of its production styles.

“Black Rave”—that’s a great way to think about the sonics of insurgency, a phrase that brings politics back into dance music and culture. Electronic dance music comes from a place of politics, as much as musical purists and Twitter trolls love to insist that “race doesn’t matter” or that “it’s just about the music,” never mind who gets booked to play that music. In the issue, Blair Black and Alexander Weheliye do a wonderful job reminding us of the strategic ways that Blackness and queerness have been removed from electronic music. Which is why the word “rave” is such a racialized one, even as Black people have been raving from the jump.

Given the whitening and cishetero masculinization of techno since the 1990s, what might it mean to reimagine techno—both in the limited and general sense—with not only Blackness, but also Black queerness and transness at its center? Is this reinvention even possible, let alone desirable in 2022? Why aren’t the electronic dance music genres most important to Black queer and trans folks included in the category of techno?

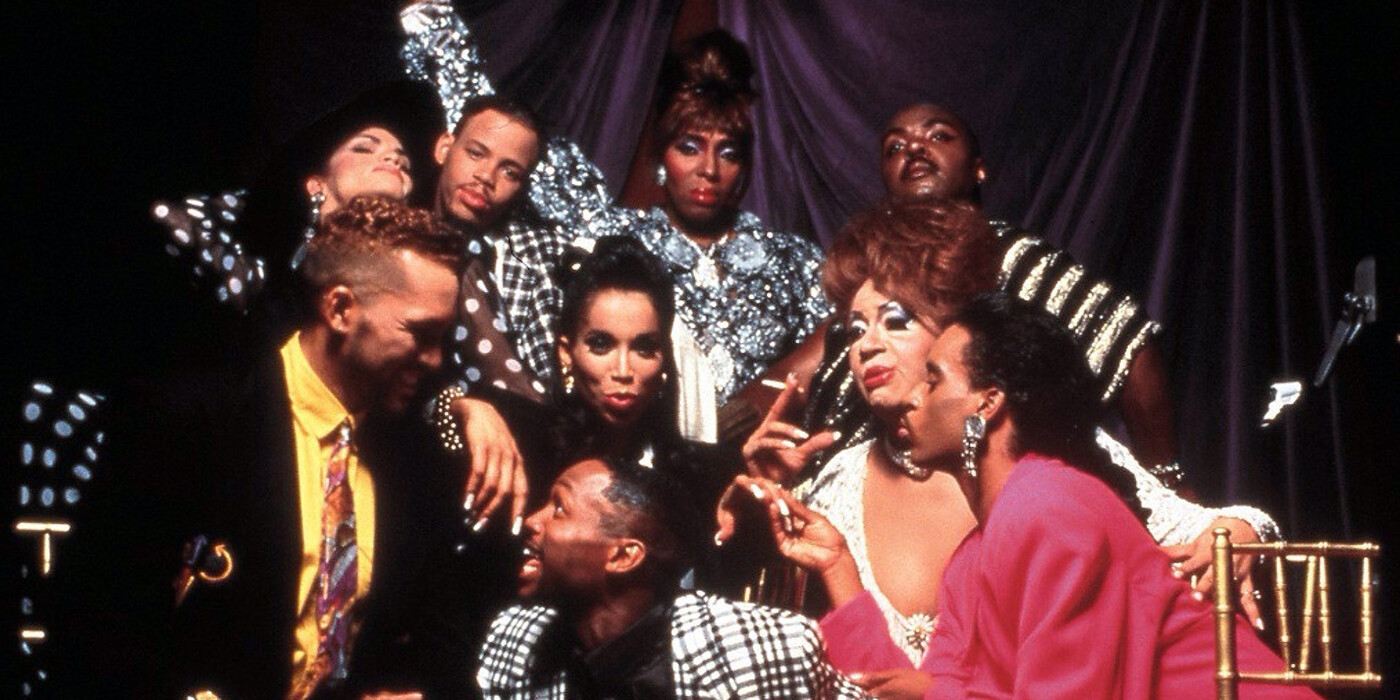

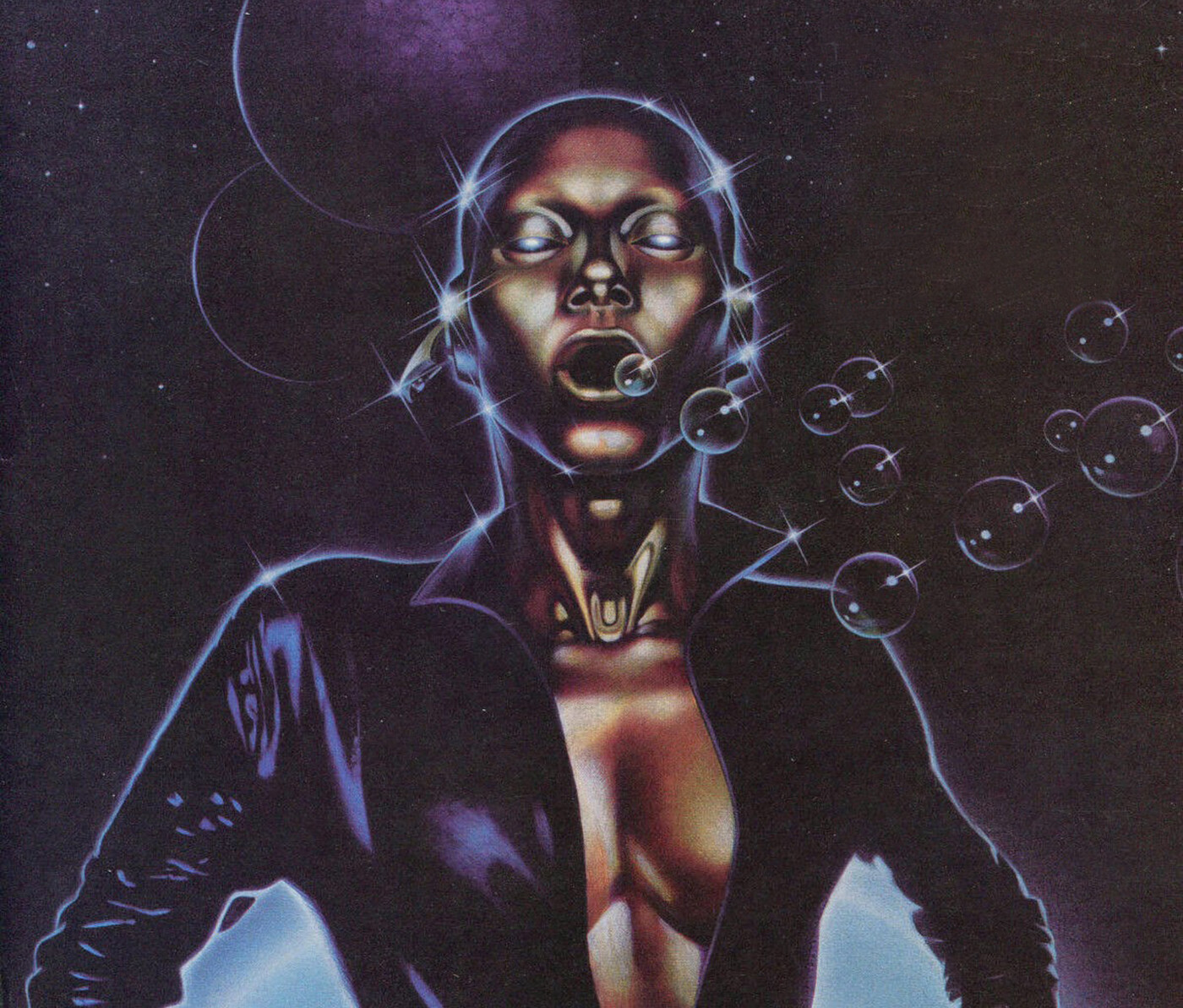

The club helped create someone like me. The club helped create someone like Juliana Huxtable. It’s a school. We taught each other. Like a science experiment. It works because there could be that one night when we really got to live. Every single bit of those little times that we had we can recall like “oh girl remember when we just lived?” That’s where I do believe the revolution is still there.

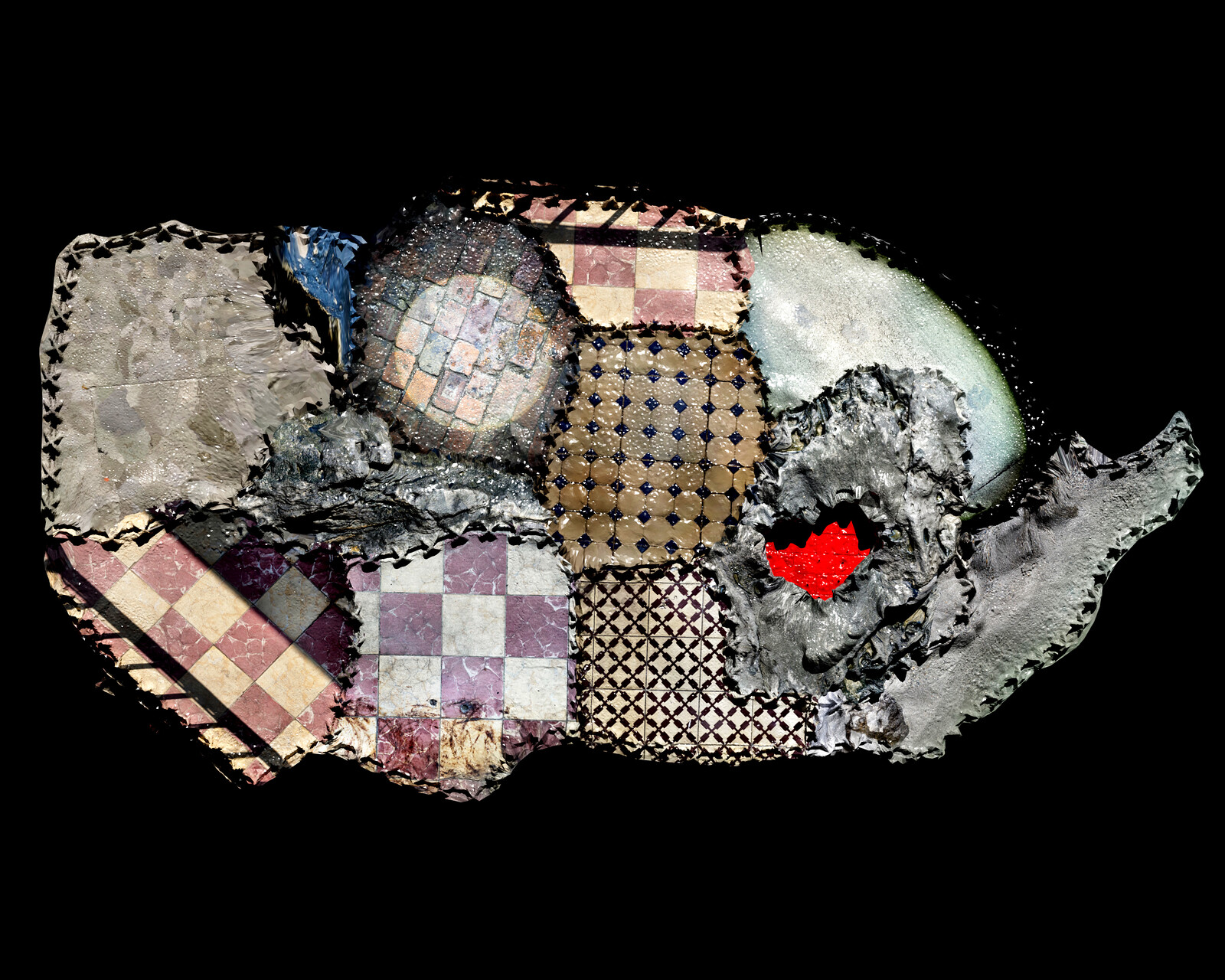

I look at music as a sculptor might. I get the materials and just have this lump of sounds sitting there, and then I chisel away at it until it starts to sound like something. I say it’s techno, but I’m not sure that it’s actually techno. What is techno? That’s a question. But maybe what my music does is define what it could be, or what else it could be. Genres can be limiting.

The ballroom scene’s Black queer frequency sonically creates opportunities for its members to refuse understanding themselves and their journeys in accordance with linear notions of time (past, present, and future) and hegemonic conceptions of “progress.” Ballroom’s Black queer frequency enables its Black and brown members to create, cocreate, mix, and remix their own stories and the meanings derived from their embodied knowledge in ways that measure “progress” as a process of continual transformation rather than a final product.

When I entered the crowded garage, I noticed there were few white people in the place. Everybody danced as if the world would end before the party did. The looks were great, and the crowd, uninhibited, was doing the funk moves known as sarrada. At Base, things still hadn’t picked up—only a few technocrats were moving on the dance floor as if they were still warming up for the big race. Meanwhile, O Bronx was already on fire!

If noise and trauma have something in common, it’s likely that—to paraphrase sound art scholar Salomé Voegelin—they both “ingest” us: both noise and trauma work on our entire body. To approach the prevalence of noise among trans femme artists and musicians is to sketch multiple contours of living as trans, as femme, and as artists in a world shaped by white supremacist, capitalist, and patriarchal systems of subjugation.

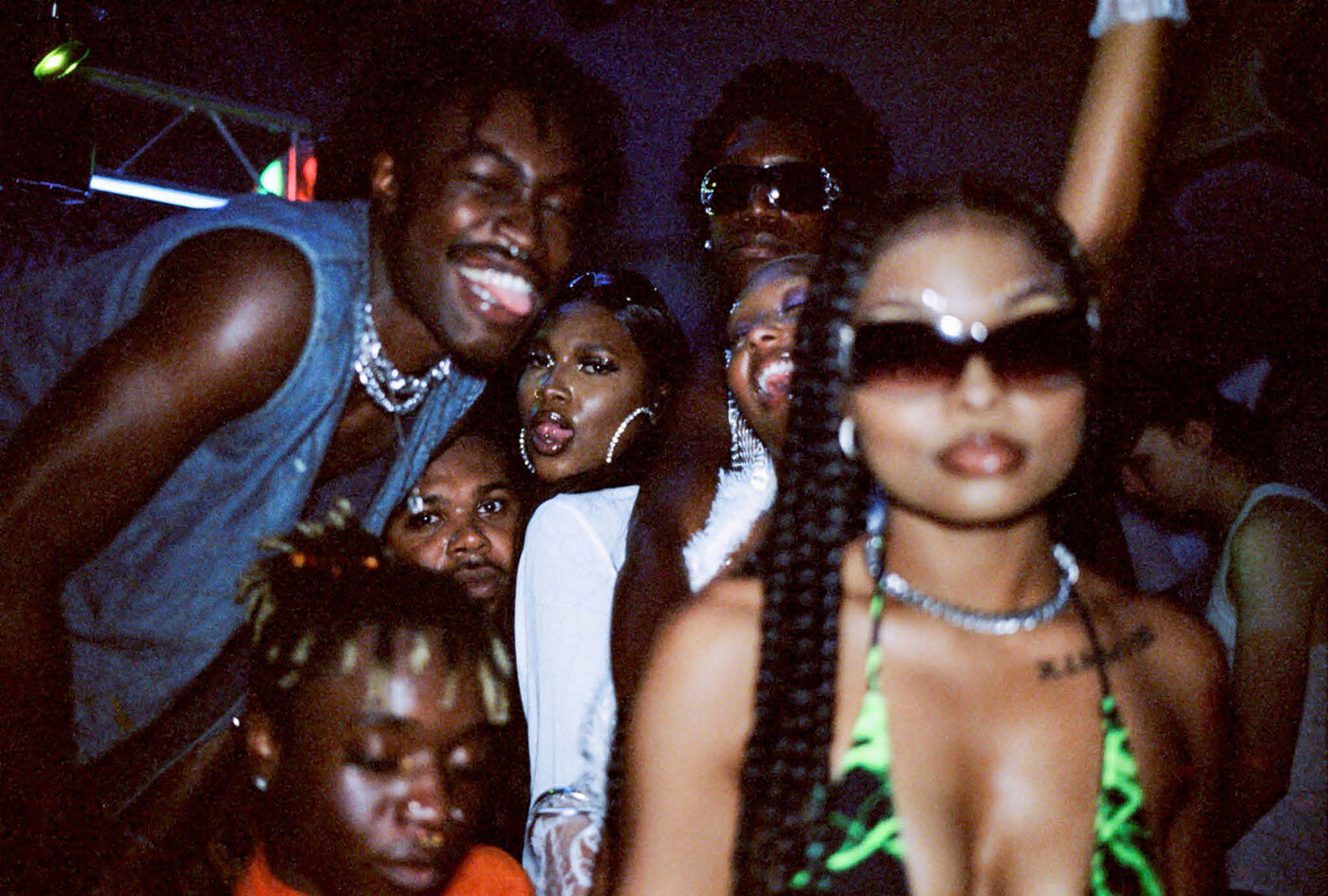

Hood Rave is an ephemeral architecture, a structure of feeling that emerges in the gaps of institutional space, after hours, in darkened space. It plays off certain physical structures and technologies, including the sound system, colored lights, warehouse architecture, and open outdoor space, and uses them to create something that actively pivots away from white patriarchal hegemony. It is a space for Black queer people and femmes to play.

What do they know of techno, that only techno knows? This is a good question to ponder, I suggest, even though or perhaps because it has no answer. The very act of asking it, without the capacity of a satisfactory answer, delivers us to that paradoxical space of affirmative negation. This is the space, I think, that is in turn necessary for “unlocking the groove” wherein the difference that techno is and still might yet be lies.

Techno is and always has been a site for the experimental. There is a certain catharsis that comes with its inert funk and drive that exquisitely blends the machine with the corporeal. As a selector and a participant in rave and nightlife, the ways in which we can manipulate and bend time, or even make time, are quite clear to me. There’s something intertwined with how we perceive the passage of time, in relation to how quickly/slowly things are moving around and through us.

Techno coincided with my own personal journey towards freedom. At Berghain, we used to talk about being upstairs or downstairs. When you go up upstairs, it’s a totally different vibe. Downstairs feels much more loose and free. I have always loved house music and I probably always will, but it doesn’t give me the cathartic relief anymore, not as much as techno does. It’s the aggressiveness, the abrasiveness, the hardness.

The beats, weaponry, the disused warehouse spaces, seized, even if only for a little while. Outside: noise, disorder. Inside: sweat, erotic release, other beginnings. Refusal. For queer-of-color life, these practices of refusal work as a fire alarm system that signals the state of emergency of Black and brown people, a sonic resistance to life as contents under pressure.