Continued from “Emotional Patterns in Art in Post-1949 China, Part I: Community of Feeling” in issue 129.

Emotional production in China after 1949 was not a carefully directed romantic melodrama. Radical transformations in national ideology, the artistic politics that accompanied those transformations, new creative forms established by artistic institutions, the ideological transformation of artists, and the left-leaning or ultraleft atmosphere that permeated the whole country all endowed emotional production with complexity and conflict. Just as political rationality concealed the ambition to change the world overnight, emotion at this time was not just committed to understanding individual existence, but also to narrating the new world order through art. And it did so by expressing critiques of the bourgeois and feudal classes of the old order, and by shaping ideals within and beyond the socialist order.

The hesitant farewell to the layers of individual existence and the near-inescapable obsession with modernism were mixed with the rationalized pursuit of a revolution in subject-object relations and of ultimate freedom to create a unique aesthetic determination. Looking back at this period today, these aspects all portray variations on themes of desire and illusion. However, in the period’s complicated historical development, we can still carefully distinguish paradoxical manifestations of states such as “construction,” “subversion,” and “indulgence.” Emotion creates a unified linkage between the vast body of the nation and the complex heart of the individual, becoming a fable by which we can now understand our own history.

Students participate in demonstration as part of the May Fourth Movement, 1919.

1. Problems of Creation and Problems of Framework

After 1949, the cases of artists Wu Dayu, Shen Congwen, and several others could be said to stand in opposition to the official art framework. This framework was produced by bureaucratic art organizations and socialist collective directives or mobilizations, as well as through the tenets and controversies over realism in periods of political tension. When these artists were criticized or completely rejected by the official art system, they responded with silent and self-sustained periods of creative effort, opening up island-like realms of the individual. However, in further instances post-1949, artists would inevitably come to be enveloped by political discipline, leading to irreconcilable conflicts between hearts and hands.

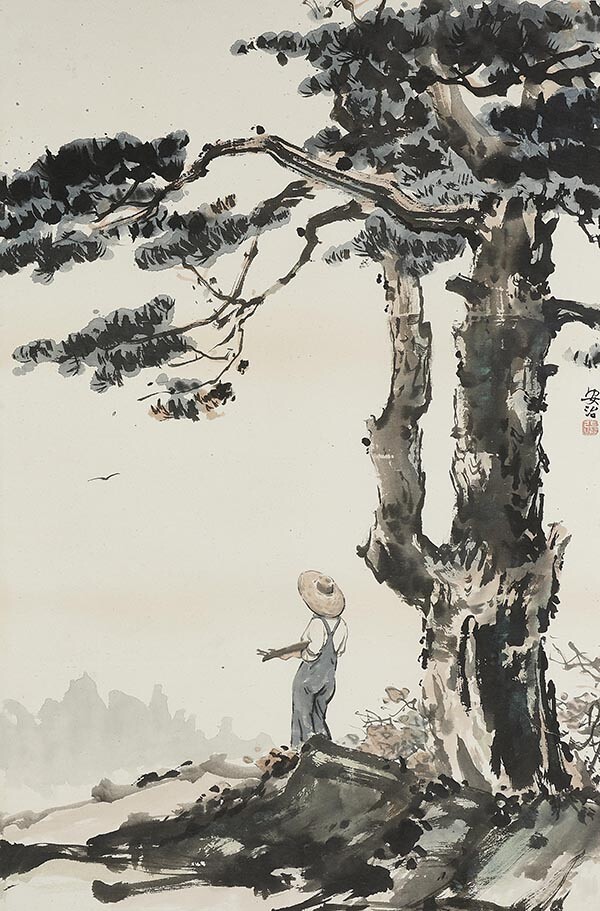

Art theorist and painter Zhang Anzhi (1911–90), who once studied under Xu Beihong, poured most of his energy into the creation of a national painting tradition. He also attempted to redefine the remit and value of state painting in socialist art from a theoretical perspective. On one hand, he took great pains to adapt the realist “art for life” approach that Xu had proposed as a response to formalism in art during the May Fourth Movement. At the same time, he drew on theory from numerous sources to link Chinese traditional ink painting to natural scientific relationships, the inheritances of ancient art for the new man, and traditional brushwork techniques, with the goal of reconstructing a universal connotation and legitimate place for China. The comprehensiveness of this theorization not only avoided political risks, but also demonstrated that the theorist sincerely believed art to be capable of “creating emotions for a new world.”1 Unlike many theorists and high-ranking artists, Zhang Anzhi took a more relaxed and tolerant approach to the tensions between Republican art and the New China, and managed to avoid sinking into the boundless pain of ideological transformation. Whether addressing a Chinese ink painting depicting the construction of a reservoir or the transformation of nature, or paintings answering the call for “revolutionary romanticism” inspired by Mao Zedong’s poetry, for Zhang Anzhi these all carried emotional connotations of the new era.

Zhang Anzhi, Looking Out.

In a review of an exhibition in the early 1960s, Zhang Anzhi wrote: “Many painters try to reflect life from one side, prizing more subtle techniques and pursuing a lyrical wit; others use symbolism and metaphors to enhance their expression of character.”2 In the same article, he euphemistically discussed a diversity of styles and themes. Through discussion of topics such as lyricism, vitality of character, and diversity of theme, he alluded to the broadness of the creator’s “thoughts and feelings” (思想感情) as unrestrained by dogma.3 At the same time, he also hinted to those in power that it is only when an artistic carrier is loaded with the rich “expression of the soul” (心灵的表现) of its author that it can move the emotions of its audience.

Many of Xu Beihong’s disciples, including Li Hu (1919–75), Wang Linyi (1908–97), Zong Qixiang (1917–99), Dai Ze (1922–), Li Ruinian (1910–85), and Zhang Anzhi, in spite of being within the post-1949 official art system, still could not compete with the political status of artists from the Yan’an Revolutionary Base. Even so, they played an important role in the making of art in the New China, especially in art education. Having been trained in realist methods under Xu Beihong, they had absorbed Xu’s schematic ideas on national art education and creation, in which fusing Chinese and Western approaches could situate a broadly framed interaction with the world through art.4 Their role in education meant that their reasoning and logic was still broadly disseminated within the new official artistic framework, profoundly influencing the artistic efforts of the new generation.

Compared with the individuals outside the official art system, those who worked for a long time within it were required to be more specific in their technical handling of line, color, and form. They had to be more consistent in feeling and expression, while also finding a balance between style and the political requirements placed on their work. Confined by the nature of their time, they were caught amid an “art-politics” debate that had already lost sight of its original aims and direction. While many works were produced during organized creative activities and strongly reflected discussions on collectivism, often those works did not represent the whole of an artist’s career. In China there have recently been a succession of exhibitions revisiting and researching the artists of this era, with some works appearing for the first time today that seem to completely contradict the art history we have grown accustomed to. Works donated to state-owned art institutions, research funded by foundations established in the names of older-generation artists (alongside work done by the families of these artists), and the socialist-period works that occasionally come onto the market provide us with sufficient reference to comprehensively examine the careers of different individual artists.

Many painters emphasize the importance of “sincerity” in their work, a simple expression that belies a much more complex entanglement of history and personal feeling, and the continuous movement of art returning to itself from the disciplinary politics surrounding it. Specifically, “sincerity” also refers to the mobilization of the artist’s hands and eyes by the principles of realism and the new era’s demand to balance the effects of tremendous interventions into objective and subjective worlds. Abstract moral standards are not adequate to measure this form of limited sincerity from the perspective of the present, since for artists it included a general belief in the ideal world declared by the new regime, a loyalty to art within their own respective contexts, and a desire to transcend the here and now. The work of artists to restore or reconstruct a sincerity in their actual work helps us understand how individuals are able to partially transcend the framework of socialist art, but also to more accurately analyze its substantive transformations.

2. Unseen Sketches

Artists’ preparatory drafts and artistic studies often transcend the scope of mere practice. They can be based on the principle of sketching from life or aim at capturing the feeling or a certain moment. They can be recollections and manifestations of pre-1949 art or lingering echoes of a certain mood or emotion. Drafts and studies convey the artist’s desire for sincerity, and to a certain extent, release the possibilities of artistic language itself under the principles of realism. These can include studies exhibited publicly in the “Chinese Painting Study Exhibition” (国画习作展览会) held in Beijing in October 1961—which included some stylistically unique Chinese ink paintings from the new era connotating experimentation and exploration—but also works that were not legitimized through public display during the socialist period and are only now being excavated or shown in the present.

These drafts and studies are significant partially because they were created in the socialist period but could not be exhibited, and also because they bear limited traces of Soviet-style art education. More importantly, the artistic discourses and techniques they carry conceal the rupture of different artistic traditions around 1949, and attempts to retain and explore them through the volatility of socialist society. The artist Wu Dezu (1923–91), who had once studied oil painting with K. M. Maksimov (1913–93), once said about sketching:

Slow drawing and fast sketching are both mostly about practicing with our hands; using our hands to quickly convey the feeling of the outside world, using hands to sketch out one’s own courage and bravery, using hands to convey one own’s weight onto the page. Paint as you wish, don’t get bogged down, this is akin to practicing use of the brush in Chinese painting.[footnote Symphonies of Color: Famous 20th Century Oil Painter Wu Dezu, ed. Wu Weishan (Wenhua yishu chubanshe, 2018), 210.]

Wu Dezu arrived in Yan’an in 1941 and studied at the Lu Xun Academy of Arts and Literature. Like many painters of his time, his works were often concerned with real life on a revolutionary basis. He dealt with people engaged in production as a starting point, and through listening, observation, and personal experience came to a three-dimensional understanding of his subjects. He would use his paintbrush to swiftly record his own creative journey as he went. He retained many pencil sketches completed before 1949, studies that not only reflected the universal, sincere pursuit of art to serve the people in the Yan’an period, but also encoded the artist’s own understanding of the relationships between tradition and modernity, “local” (土) and “foreign” (洋). Wu Dezu was a talented portrait artist, and skilled in the use of color. In his teaching, he stressed that “colors should be deployed quickly, and if they become dirty, they should be wiped off.”[footnote Symphonies of Color, 303.] This can be differentiated from Xu Beihong’s principles for color mixing, but also hints at the importance of feeling in the moment of sketching. Although Wu had been extensively trained in sketching and drawing from life, he was not confined to any academic creative dogma. He attempted to establish a direct relationship between “I” and the “object.” This kind of sincerity approaches “the people” with a humanistic simplicity, and molds the figure of the “simple man” through a dialogue between technique and feeling that cannot be completely reduced to “the people” as framed by political discourses after 1949.

In fact, in the early phase of China’s importation of Soviet art education, technical training was conducted simultaneously alongside the cultivation of artistic sensibility rather than merely as a new codified or limiting creative method, as the Maksimov oil painting class, which opened in 1956, can partly verify. After 1957, however, the idea of carefully cultivating artists was swiftly abandoned and the art world was rapidly politicized. A series of dogmatic standards for art were adopted, and those artists who had received early Soviet-style art education—many of whom had grown up during the establishment of New China, some having begun their artistic careers in revolutionary bases like Yan’an—still retained the artistic habit of following one’s own emotions and sensibilities as well as the principles of realism. After the mid-1950s this habit was increasingly suppressed and called into question by the entire art system, and the “studies” that artists completed privately were rarely displayed in public. Yet the small sketches created on the road at home and abroad, or the lyrical works created during periods of political relaxation, often intentionally or unintentionally show a commitment to this portrayal of emotion.

3. Regulating Emotion Between Mainstream and Fringe

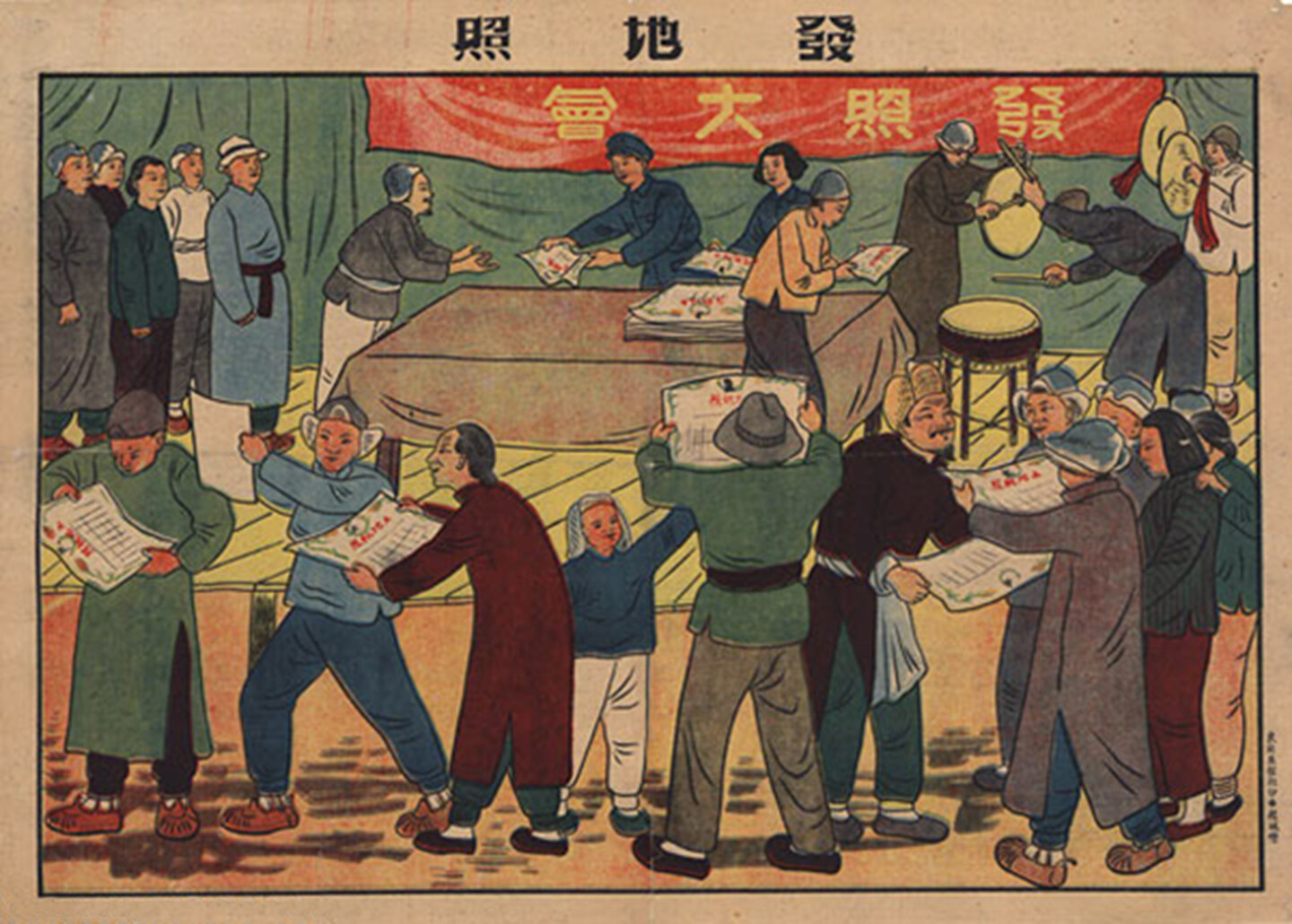

On the other hand, in addition to a dogmatic tradition of art education, the new era also gave rise to new forms of painting. This led to differences in political status for certain kinds of art, and thus also in the sincerity and forms of emotion assigned to them. New Year Paintings, comic strips, and propaganda images (年连宣), all of which had been important in Yan’an-era propaganda and mobilization, had long occupied a dominant position. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, works on themes of revolutionary history by local Chinese painters also matured.[footnote The Path of China’s Modern Art, ed. Pan Gongkai (Beijing daxue chubanshe, 2012), 354–57.] Traditional Chinese ink painting in the new era elevated sketching as a methodology, and hugely influenced the fields of character sketching and colored-ink figure painting.[footnote The Path of China’s Modern Art, 382.] The enthusiasm for oil paintings on national themes during the Hundred Flowers Campaign and the Great Leap Forward seemed to provide oil painting in the New China with an internal impetus to escape Soviet influence for the first time. Once this style of painting and reforms to it were officially recognized, it was introduced across the whole of China through organized efforts and political decree.

However, as with other kinds of painting—landscape oil painting, portraiture, literati painting traditions, watercolors, abstract painting, and the works in colored ink (彩墨) briefly developed by Jiang Feng (1910–82)—this national style of oil painting also encountered fierce ups and downs. In a volatile and polarized landscape where mainstream faced off against fringe, many issues of concern for Chinese art became merely secondary: China’s regional artistic traditions and cultural heritage, modernism’s continuing influence, and attempts to integrate dialogues with the West, the Soviet Union, and different regions of Asia. If we are to look at what kind of emotions were encoded in the different genres of painting by their creators, we must first think about the overall situation they were in. We need to carefully distinguish between performance and political/artistic appeal rather than use “sincerity” as the only yardstick for measurement.

Isaac Levitan, Over Eternal Peace, 1894.

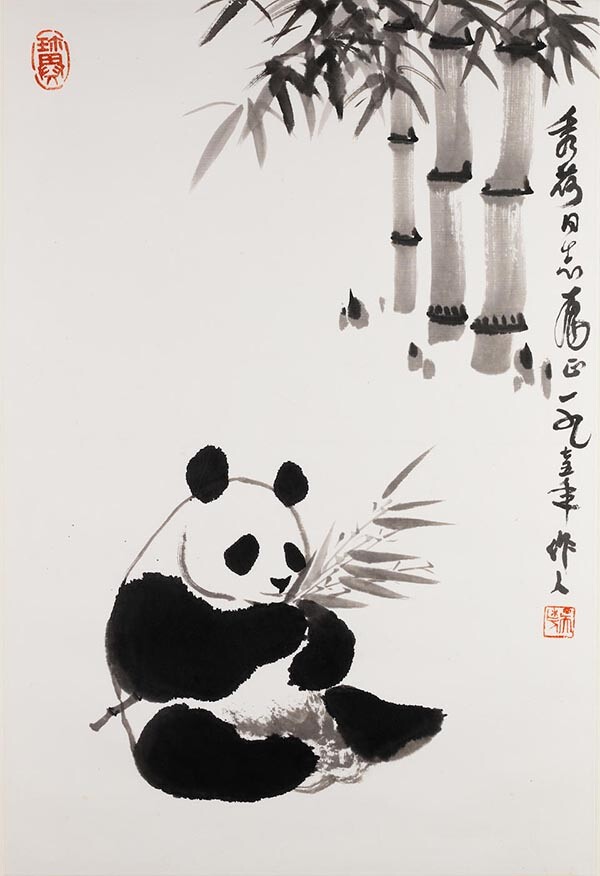

The political status of certain genres of art represents their legitimacy in the public domain due to political reforms, but also due to the collective will and joint efforts of the art world. For example, “Paintings after Mao Zedong’s Poetry” (毛泽东诗意画) rose to prominence in the Chinese art world after Mao Zedong’s eighteen “classical” (旧体) poems were first published in the first issue of Poetry (诗刊) in 1958, yet the portrait and landscape paintings of Russia’s late-nineteenth-century Wanderers (Peredvizhniki), which were introduced to China alongside Soviet realist art and were hotly debated by artists prior to 1957, had little political legitimacy after the late 1950s. This was not because the educational foundation for landscape and portrait painting was lacking, as Wu Zuoren (1908–97) once concluded in a discussion of landscape painting, nor was it necessarily due to political orientation.[footnote Selected Writings of Wu Zuoren (Anhui meishu chubanshe, 1988), 144.]

Taking landscape painting as an example, if the landscape is seen as a kind of “epistemological constellation” (认识装置, according to Karatani Kōjin) or an historicized form for perceiving nature, then landscape paintings in the new socialist era could not or would not be permitted to be products of “naturalism” (自然主义). Instead, they must accommodate the ideological requirements of the new era and its perceptual experience. This inevitably requires creators to provoke a new subjectivity, and to create images presenting the ideological requirements and ideal landscapes of the new era. As with mainstream genres, landscape and portrait paintings needed to be “consistent” (相契) with the objects they represented.[footnote Selected Writings of Wu Zuoren, 154.] This “consistency” is a basic principle of socialist art, but is also a reflection of the creator’s own thoughts and feelings. The emotions of the artist as conveyed in landscape paintings shared with mainstream genres of painting and the novel genres of the era an understanding of the new world and its subjectivities.

We cannot make a clear distinction between regulated emotion and sincere emotion. On the creative level, artists working in landscape themes could more easily immerse themselves in a private and more equal sensory encounter with the subjects of their art. In mainstream art, this immersion was obviously more tortuous for being subject to significant restrictions and ideological demands. This was particularly the case in 1958, when “the combination of revolutionary realism and revolutionary romanticism” became the guiding principle, and when the demand for the creation of reality far exceeded that for the description of reality. However, we cannot identify in the emotional states depicted in mainstream/secondary genres of painting any schism between public/private, political/artistic, or state/self. The distance between mainstream and fringe was relatively wide in times of political crackdown, but in periods of political relaxation, it was often mainstream discourse itself that proposed to give more space to the techniques and emotions of suppressed or fringe genres of painting. Rather than create a moral distinction between regulated emotion and sincere emotion, it would be more appropriate to clearly recognize the common historical “dynamic” that encompasses both mainstream and fringe genres, whether within the socialist art framework, transcending it, or both.

The confrontation between creative activity and the socialist framework for the arts was in fact present throughout the entire Maoist period, more obviously in periods of political relaxation. And while the confrontation took place under the principles of socialist art, such principles could also themselves be questioned—in their manifestation as dogmatism, for example, or in the indiscriminate use of vulgar sociology to promote work calculated to please rather than to challenge or educate the people. Sometimes confrontation between questions of creative practice and artistic framework also meant that neither was able to penetrate the other field, each forming a closed circuit, while at other times dialogue between the two fields was sufficient to generate new paths forward, both shared and divergent. The interactions between creative work and artistic framework during the socialist period were by no means a simple antagonism or irresolvable conflict between public and private. This determines the basic situation in which artworks and artists, and their internality and transcendence, are defined by the socialist framework.

Wu Zuoren, Panda, 1975.

From the perspective of the artist, a choice between internality or transcendence is not derived entirely from individual consciousness, nor from being required to either follow or fight against official demands in a collectivist context. Since there is no framework for art that is either completely contained or entirely able to transcend the official socialist framework, there has to be an unconscious realm—a position by which residing within the framework does not exclude transcendence and transcendence need not abandon the framework. This “unconscious” is historical in nature, i.e., it exists within the inexorable laws of history. On an emotional level, when artists and artworks are in this unconscious realm, it is possible to open up slightly amid the political atmosphere, to express emotions through the cracks of collectivism and describe being an autonomous individual in a time of heightened ethnic or national emotion. These expressions may be reenactments of modernity or may revisit national artistic heritage, or may emerge simply from revolutionary sentiment. Adopting a naturally decentralized rhetoric, such expressions may appear asocial, ahistorical, and not so “real,” thus avoiding any invasion or desecration of the framework in its essence.

Some controversy emerges from amid the internality/transcendence dialectic. Precisely due to this unconscious realm, both artist and framework have the space to extend their own internality, activate their own vitality, and even deny their own staleness (陈腐) in order to open an orientation toward the future. We can take two specific controversies surrounding the question of “innovation” as examples. In 1962, the film theorist Qu Baiyin (1910–79) published a widely discussed article entitled “A Monologue on Film Innovation” (关于电影创新问题的独白) in the magazine Film Art (电影艺术). The author describes the distress of art workers plagued by political regulations and artistic dogma, calling for innovative practice based on the principles of art alone. This article, published during a period of political relaxation, raised the question of “innovation” as a discussion of what he referred to as “truth.” Qu wrote: “Truth and rhetoric are two different things. Truth must be repeatedly told, but we must not use rhetoric, but rather use new ideas to tell it. The use of rhetoric causes truth to lose its crystal clarity, whilst new ideas will allow the truth to radiate an eternal light.”5 Rather than accuse the state for its comprehensive control of “truth,” the author uses artistic “innovation” to pierce the closure of “truth,” to stimulate its renewal and opening.

The dramatist and filmmaker Xia Yan (1900–95) noted that Qu’s article ponders already “old problems” of artistic creation in that period.6 However, Qu’s perspective for tackling the question of “innovation” is entirely new, and accurately captures the unconscious field as a common driving force for both artistry and the artistic framework it confronts. For Qu, “innovation” in art is not only its essential characteristic, but also a new (and even radical) grasp of a new reality of the times. At the same time, the artistic framework of the new era must be constantly renewed through artists’ innovation in order to coordinate art practice. Further, Qu argues that new subjectivity is a prerequisite for discussing “innovation.” The emotional, moving passages of the monologue and the power of its sincerity not only cry out for humanistic and artistic independence, but also reveal a reflection on subjectivity in which “the ‘revolution of the soul’ that transforms or remakes the people’s subjectivity” is a kind of “truth,” hinting that this “truth” is constantly being created.7 At the same time, socialist art, as another form of creation, echoes the creativity of “truth,” and must also seek innovation and motivation from art itself.

Looking back on the art history of the socialist period, the process of self-transformation according to the will of the state emerges as the heart of the problem. Socialist art has clear modern characteristics, and it never completely abandoned the understanding of the modern individual that emerged from capitalist production and culture: an individual that can surpass itself infinitely, is unrestricted by natural conditions, exhibits a spiritual refusal of Man’s limitations, and possesses a belief in endless expansion supported by reason. The artistic transformation of art under socialism took the modern individual’s continuous transcendence to an extreme. In addition to the endless debates on form and content, theme and thought, reality and progress, each individual’s presentation to the world was no longer as a vulgar self, but rather as something transcending the self—a higher, abstract self that embodied the will of the nation. But then in a Hegelian respect, works that embody the will of the state are not merely narrations of history that legitimate the history of a party, but also narrations of the self. Or we might say that works appearing to be merely “sketches” in nature—unrelated to the ferocity of realism—are not only a view from within the confines of one’s own feelings, but also a form of historical narrative, centered in the knowledge of the self as an alternative expression of an intrinsic discourse.

In this fashion, the layers obscuring emotions can be removed to escape ceaseless interrogation under socialist conditions. Emotions are nothing more than the condition of mind revealed when the individual, driven by self-knowledge, ascends to the collective; or alternatively, when dialogue and conflict occur between the individual and the collective. In terms of art itself, emotion can often act as a bridge between narrative and lyrical poles, opening the possibility of dialogue with modernism, Chinese tradition, and popular culture. Here, emotion carries the silence, resistance, and hesitation of the artist undergoing the process of self-transformation. From the perspective of the entire cultural process, it was through emotion that art praised (rather than simply reflected on) the process by which new subjectivities of the socialist period shaped themselves—inspired by the demands of forming a new collective.

4. Emotion: A Perspective for Analysis of Conceptualism

In the changed landscape of the post-1980s art world, emotional expression was once again transformed to suit new trends. With the obsolescence and transformations of “emotion” seen in contemporary art, how can we open a space for dialogue with conceptual art practice? Let us briefly turn to a few conceptual artworks created from the 1990s onwards and explore whether a framework can be established.

In 1994, the artist Yan Lei (1965–) made up his own face to look as though he had been beaten up, and then took a close-up photograph, titling the work Face (1994). The image reminded viewers of the turbulent situation of 1990s China, in which ordinary people found themselves engulfed by the torrent of the times. Starting with this image, Yan Lei’s practice revealed the complex emotions and attitudes with which he confronted commercialized society and the art system controlled by it. Another artist, Hong Hao (1965–)—who once forged, together with Yan Lei, an invitation letter to the 1997 Documenta and sent it to Chinese artists—bound a selection of his prints into a volume that purports to be a classical text. Entitled Selected Scriptures (1995), Hong used the medium of screen printing to mimic the printed texture of ancient texts. The works in his classical text include fictional maps such as the “Map of the Missile Defenses of the Myriad Nations” and “Map of World Defense Installations,” sketching out an artist’s imagination of the world order. The authority represented by such ancient classic works and the rules they encode for understanding the world became the object of ridicule, also showing the drastic changes that occurred within the inner worlds of artists undergoing the processes of globalization in the 1990s.

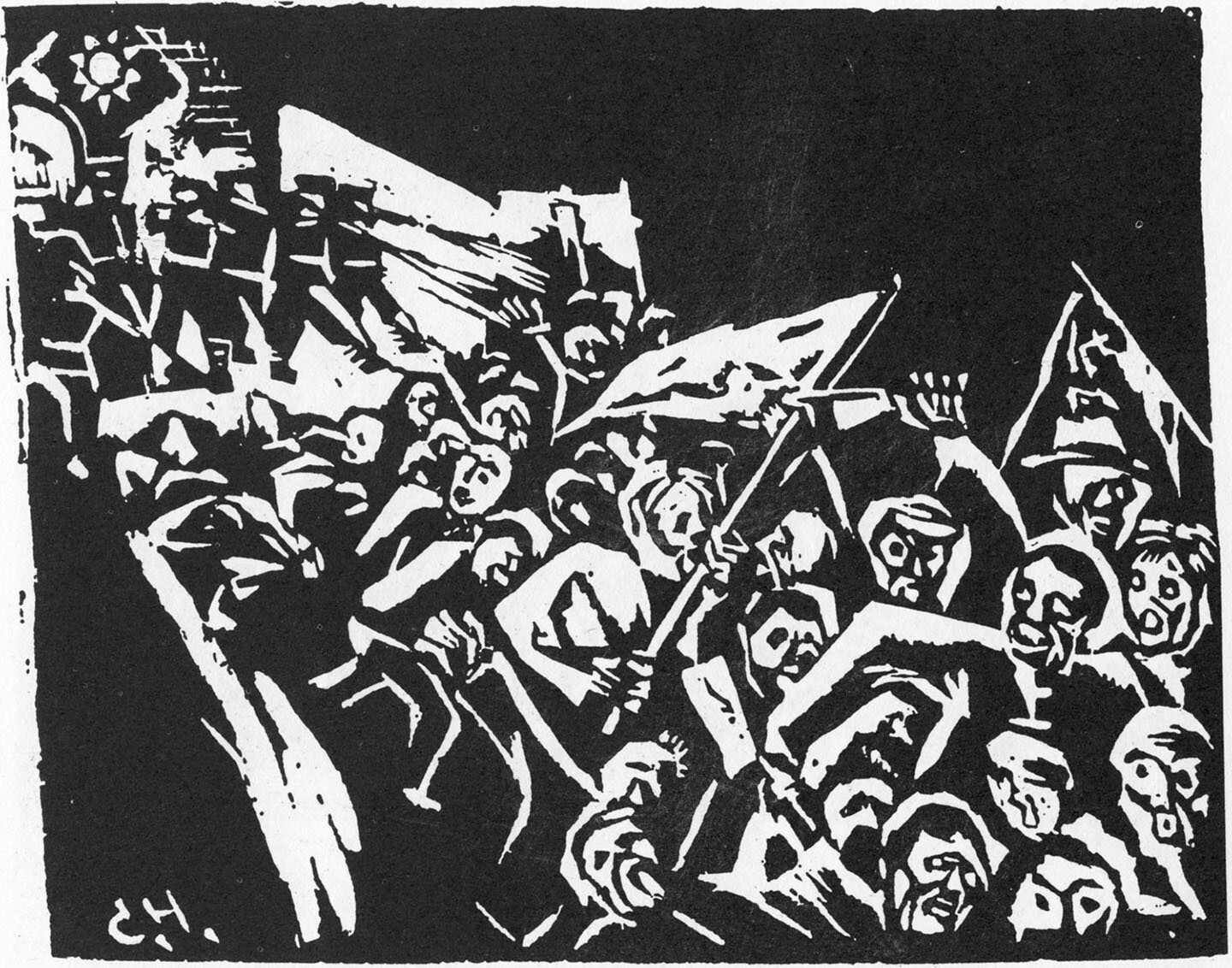

Jiang Feng, Kill the Resistersi, 1931. Reproduced from Selection of 50 Years of Chinese New Printmaking, vol. 1, 1931–1949 (Shanghai People’s Fine Art Publishing House, 1981).

The artist Ma Liuming (1969–), who resided in the Dongcun (东村) area of Beijing in the 1990s, had an experience of dressing up as a woman once, which prompted him to use the classically feminine features of his face to create a gender-fluid new identity—“Fen-Ma Liuming.” “Fen-Ma Liuming” wears makeup, and has a feminine face but a male body. This androgynous creation became the subject of a series of performance pieces. In the images of Fen-Ma Liuming, there is an anger towards prescriptions of identity, but the works also show a complex, intimate feeling (“Fen” is the name of the artist’s girlfriend). The artist Sui Jianguo (1956–), who has been in dialogue with the realist sculptural tradition, recorded his observations on his daily life in his collection Drawing Hand Scroll (2006–7). All recorded on the litmus paper used in industry, the works give the impression of emotionless contemporary engineering drawings. The artist Ma Qiusha, born in the early 1980s, condensed her own adolescent education, family, and emotional experiences into a video monologue titled From No.4 Pinguanli to No.4 Tianqiaobeili. At the end, the artist who has been speaking indistinctly throughout the video removes a bloody blade from her mouth.

Since the beginning of the 1990s, the Chinese art world has seen new orders and new trends take hold, both pragmatic and authoritative. Some artists who had arrived onto the stage in the nineties began to be wary of the status quo but were also disappointed by the grand narrative that had held through the eighties. At the time, globalization was gradually becoming a visible reality. Following the collective reappearance of Chinese artists at the international level in 1993, international exhibitions and debates also became a driving force. Within China, the art business flourished in the private sector, and the art market and art discourse became closely tied to each other. China had once again gone through a period of conceptual reformation and was swiftly becoming a commercial society. As compared with the eighties, the “reality” that art was in dialogue with had utterly transformed. This new situation gave rise to a further transformation in emotional structures. In their creative works, the artists who arrived in the nineties tried to transform their emotions, cultivated in a complex reality, into criticism of rules and functionalism, of the myth of the artist and prevailing hegemonies.

Strong emotions can allow art to transcend the confines of reality, and also prevent art from falling into the trap of vulgar sociology. Though we often see conceptual work as dry, cold, and without feeling, the spiritual depth of such works is found beneath their expressionless posture. Just as emotions have their own inner depths and are not simply unprovoked thoughts or unreliable intuitions, concepts cannot be only products of pure rationality or logical judgment. The active relationship between emotions and concepts can help us reimagine the real historical situation in which the individual is located, and the complex worlds constructed by different artists from within their respective systems. Emotion itself can be a fact, an awareness of the status quo, or a medium for conveying ideas. This understanding of emotion is not unique to China. When discussing Euro-American conceptual art from the 1960s onwards, art theorists Boris Groys and Jörg Heiser have used the term “romantic conceptualism” to articulate the dialogue between conceptual art and the realities of its cultural and social settings. However, these conceptualist practices are also contradictory, because they cannot display an understanding of the self within the art system, even though that same art system determines the conceptual strategies they employ. Emotion here is not a footnote to the dilemmas of an alternative modernism or an alternative present; it can be used as a medium to perceive the psychological states and mechanisms of art practitioners amid a framework of wide-reaching influence—the mechanisms of which may indicate the true dilemma, and perhaps suggest a few possible directions.

The new structure of emotions is once again being shaped by a unifying, normative power. Around the turn of the new millennium, Chinese contemporary art threw itself completely into the discourses of globalism. But the globalization of art is not predicated first and foremost upon multiculturalism or an imagined open world system, but upon the art system itself—a fact not recognized by all art practitioners. The practice of art presents itself as reflective participation (or a reflective performance) of the possibilities of its own system. The Chinese art world has attempted, over a brief period, to simulate a local art system consistent with (or as a feasible route to) the Western and imagined global system. Permeating this process is not a comprehensive understanding of the art system and its systemic violence, but rather a feeling for the collective process at the moment of production/reception in artistic practice.

Contrary to the version of contemporary art that imagines an infinite number of unique individuals, China’s entry into the global art system retained a strong collective character mixing a variety of desires and emotions. Whether seeking legitimacy in local or international realms or eagerly drawing a boundary between nationalism and unilateralism, whether in completely commercialized spaces or in elite alternative spaces, whether through “state” art institutions (which still exist today) or through self-proclaimed “unofficial” nomadic art practices, Chinese contemporary art has generally questioned and undermined rituals and shared consensus—and it has done so collectively. While this is not uncommon in China’s history of conceptual art, at this point almost everyone is walking in unison—collective dependence on the system and belief in power remain ubiquitous, and almost everyone has been influenced by elitism.

China’s conceptual art is, after all, connected to the history of the socialist period. Under the influence of many emotional and psychological mechanisms, the true shape of contemporary art in China remains hidden, even if it operates within the customary binaries of mainstream/fringe, elite/mass, and global/local. The changing subjects that art discusses cannot conceal the absence of change in art itself, especially amid the complex, entangled hardships we experience today, in the postrevolutionary period. At the same time, the increasingly intense political situation in China today can also make us hear the echoes of the past more clearly. Might those brief flashes of emotion in historical moments of uncertainty help us to see the maze that we are currently in?

Zhang Anzhi, Collected Writings on Art by Zhang Anzhi (Renmin meishu chubanshe, 1999), 29.

Zhang Anzhi, “A Brief Discussion on Portraiture—After Viewing a Portrait Exhibition,” in Collected Writings on Art by Zhang Anzhi, 22.

Anzhi, “A Brief Discussion on Portraiture,” 49.

For debate on Xu Beihong’s vision of a Chinese painting and creative method that fused China and the West, see Wan Xinhua, “A Discussion of the Teaching of Chinese Painting in the Department of Art, Normal College of the National Central University” in Art for Life: Collected Art Writings of Xu Beihong’s Students, ed. China National Academy of Painting (Zijincheng chubanshe, 2010).

Qu Baiyin, “A Monologue on Film Innovation,” Film Art, 1962, 55.

See Qin Suquan, “The Complete Story of ‘Innovation Monologue,’” Film Art, 1999, 5.

Wang Hui, Depoliticized Politics: The End of the Short 20th Century and the 1990s (Shenghuo/du shu/xin zhi, Sanlian shudian, 2008), 18.

This article was written in Chinese, translated by Hannah Theaker, and is published here with abridgements. The original article is based on the exhibition Community of Feeling: Emotional Patterns in Art in Post-1949 China (Beijing Inside-Out Art Museum, 2019), curated by the author, and will be included in the forthcoming eponymous catalogue to be published by Zhejiang Photographic Press in Hangzhou, China.