In times of civilizational crisis, people turn to the old stories for guidance. Religiosity surges. Nineteenth-century conspiracy theories (and older pseudoscience) get a new futurist gloss. Even the most secular politics are inflected with apocalyptic fervor. Hollywood, in this respect, is only human. Responding to the unrest among its audience, the big studios are quick to reheat popular franchises that fit the current strain of anxiety.

In a delayed response to Covid-19, for example, they have now given us a new Matrix and a new Jurassic Park—two franchises that have become synonymous with public fears of technology and science. Jurassic World Dominion, which features a subplot about a biotech corporation destroying the world’s crops, seems like a particularly clear shoutout to the anti-vax internet. As Hollywood’s metabolism gets back up to speed, we can expect to see a glut of these kinds of paranoid sci-fi blockbusters. Expect another renaissance of the mad-scientist trope, in its contemporary guise: the reckless science corporation. Expect another Alien and another Planet of the Apes. Most curiously, expect at least one attempted remake of The Island of Dr. Moreau, the most cursed intellectual property in Hollywood history.

H. G. Wells’s 1896 gothic horror novel, about a rogue physiologist who crossbreeds animal-humans and rules over them like a colonial dictator, always seems to get readapted when public suspicion of scientific innovation peaks. Wells wrote it in such a time, in response to public outrage in his native England around the vivisection of animals. It was first adapted to the silver screen in 1932 during the era of applied eugenics; readapted in 1977 after the Vietnam war implicated big science in mass murder; and remade again in 1996 during the freak-out over stem cell research. It’s only a matter of time until we get a Dr. Moreau for the age of speculative biotechnology and lab-leak theory—particularly now that actual chimera embryos (monkey-humans) have been successfully CRISPRed in a lab.1

Woodcut of a manticore from Edward Topsell’s The Historie of Foure-footed Beastes (1607). License: Public Domain.

At least one such adaptation is reportedly already in the works. Screenwriter Zack Stentz (the mind behind X-Men: First Class, Thor, and Agent Cody Banks) has signed on with former Viacom CEO Van Toffler’s new studio Gunpowder & Sky to develop the old gothic horror tale about eugenics and colonialism into a prestige television series. Like every adaptation, it is being updated to speak to the hopes and fears of the present: “World-renowned scientist Dr. Jessica Moreau’s pioneering work in genetic engineering catches the eye of a billionaire backer willing to stop at nothing to reach the next step of human evolution.”2 As promising as this all sounds, Stentz faces a daunting task. At the outset, he must have been struck by the lineage of world-class talent that has perished along this same path. Every adaptation of Dr. Moreau has belly-flopped at the box office, directors have lost their shit and their jobs, great actors have tarnished their legacy.

What is it about H. G. Wells’s weird third book that compels Hollywood studios to keep retelling it? And why has it given its adapters so much trouble? Does the novel just have too many unsavory layers (gory animal experiments, neurodivergent chimeras, nineteenth-century European racial attitudes) to compress into a viable sci-fi blockbuster? These questions lead naturally to bigger ones: Why do we keep reliving the fears and follies of the nineteenth century through endless sci-fi remakes? And, crucially, what kind of intellectual baggage is being smuggled along the way?

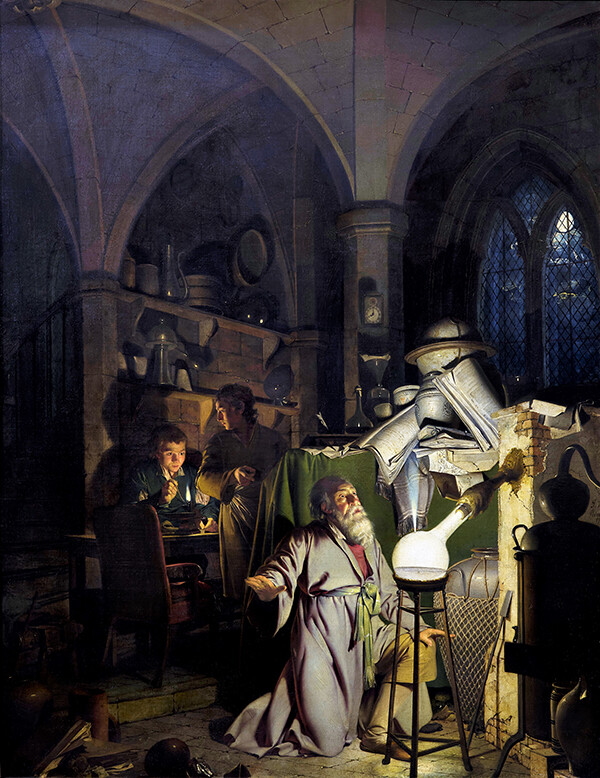

Joseph Wright, The Alchemist in Search of the Philosopher’s Stone, 1771. License: Public Domain.

Imperial Hang-Ups

The Island of Dr. Moreau appalled London’s literary critics. Repulsively gory, morally obscene, and scientifically implausible: that was their consensus. Fresh off his best-selling Time Machine (1895), the empire’s most popular young author seemed intent on dashing all his good will. Critics didn’t just think the book was bad; they thought it was irresponsible. Dr. Moreau was sure to stoke the already long-running public hysteria around animal experiments. It would make excellent propaganda for the anti-vivisectionists.

In the early nineteenth century, physiologists started dissecting animals to better understand human anatomy. The ethical outrage surrounding this practice spread from scientists to doctors, and—in the second half of the century—started to infect their patients, the English public. By the 1870s, London saw its first animal rights protests, uniting suffragists, socialists, humanists, and Quakers in a call for the legal protection of all species. The same concern spread simultaneously as a kind of folk knowledge through the public imagination. One might think of it as the scientific conspiracy theory du jour. In that variation, demonic (usually French) scientists were tampering with nature and would soon conduct their horrific experiments on human beings. Rumors abounded about the unnecessary cruelty of their experiments, and their unbridled ambitions to remake everything. H. G. Wells brought this nightmare to life and common English readers face-to-face with their bogeyman: a continental pervert playing God.

In his old age, Wells came around to agreeing with his critics, describing The Island of Dr. Moreau as an “exercise in youthful blasphemy.”3 He grew especially disgusted with the material when he saw it boiled down to its coarsest elements in its first Hollywood adaption (The Island of Lost Souls, 1932). By then, he must have had a pretty good idea of what kind of nightmares he had unleashed on the world, and that in posterity he would have little control over what they would convey. This is the perk and the risk of great sci-fi writing: the long-standing influence of your vision, and your lack of influence over its interpretation.

Hardly anyone was as enduringly influential, in ways intended and not, as the man routinely described as either the Father or the Shakespeare of Science Fiction. Wells’s great scientific romance novels would establish whole subgenres. Every alien-invasion blockbuster is indebted to his War of the Worlds; every time machine refers to his Time Machine (he coined the term); many invisible men owe something to his Invisible Man. Though obviously building on the myth of Prometheus and Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, The Island of Dr. Moreau is the first example of a subgenre called “Uplift,” where people (or aliens) intervene in the evolution of more primitive species, often with the goal of making them more intelligent. Though it may sound niche, this theme would echo prominently in Bulgakov’s Heart of a Dog, Keyes’s “Flowers for Algernon,” Boulle’s Planet of the Apes, the Jurassic Park series, as well as numerous other nineties dystopian biotech flicks.

Frankenstein, directed by James Whale, 1931 (film still).

Traditionally, this kind of intergenerational resonance has been chalked up to the genius of great men, but that doesn’t really tell us very much. Wells was just a supremely adept plotsmith, who happened to be a science nerd during a time of great scientific revelation. Born in 1866, the son of a trifling businessman, he came to intellectual maturity just as Darwin’s theory of evolution, Mendel’s theory of genetic heredity, and Mendeleev’s periodic table were being absorbed into the public consciousness. At university, he studied biology under the preeminent Darwinist Thomas Henry Huxley (grandfather of writer Aldous), who had responded to Charles’s famous theory with the line: “How extremely stupid not to have thought of that!” By the time Wells realized he was too stroppy for real science and dedicated himself to fiction, streetlights were springing up all over Europe’s cities; astrophysicists were starting to compute the infinite possibilities of outer space; and crude race science was considered educated conversation, even among avowed socialists.

Wells’ overview of all this reckless innovation, paired with a knack for turning speculation into standard-bearer plots, set the stage for his crazy run in the 1890s. Reading his scientific romances now, one apprehends an author who was able to balance his biases. They are dialoguing with each other, particularly in Moreau: The utopian scientist who thought science (even eugenics) could uplift humanity in unimaginable ways. The socialist who worried that, in the wrong hands, the same innovations would solidify a permanent underclass. The progressive Englishman of the late nineteenth century who was a cautious critic—but completely the product—of empire. The mischievous young plot-craftsman trying to both engage and trigger his readership.

Keeping all this in mind, the plot is worth beholding. We see the island through the horrified middle-class gaze of our shipwrecked narrator Edward Prendick. At first, he’s chuffed to be standing on solid ground and to get a room in Moreau’s compound. But then he starts to piece together who the doctor is: a notorious scientist who was banished from polite society for performing horrific animal experiments. Our narrator peeks into the compound lab and witnesses an animal being vivisected. Fleeing out into the jungle in disgust, he starts bumping into the products of Moreau’s lab work: several generations of animalistic humans living in a slum, celebrating their maker like a God.

When confronted, Moreau explains his project with considerable satisfaction. He and his alcoholic sidekick Montgomery have been grafting human features onto different animals. He believes this may yield the perfect race, particularly once the chimeras have internalized his distillation of civilized human morality. The beastfolk recite a chant, vowing “Not to go on all-fours … Not to suck up Drink … Not to eat Fish or Flesh … Not to claw the Bark of Trees … Not to chase other Men.” Only to conclude: “That is the Law. Are we not men?” If they break this pledge, they are literally reformed by their maker. For “His,” they acknowledge in chorus, “is the house of pain!”

Moreau blends science and philosophy into smooth arguments. He is more complicated than a caricature of a mad scientist. He is Wells expressing his utopian argument in dialogue with Prendick, who himself channels the author’s fear of degeneration and dystopia. At least the doctor is clear-eyed enough to see that his beastfolk are a work in progress. They require constant surgeries and endless propaganda if they are not to devolve back into their animal ways. This is the only way to guarantee human safety on the island. Prendick finds out this for himself when he discovers a rabbit carcass, which suggests that one of the beastfolk has broken Moreau’s monopoly on violence. The suspect, Leopard-man, is identified and pursued by Moreau’s cavalry. Prendick catches him and, seeking to spare the valiant rebel a visit to the House of Pain, shoots him on the spot. This outbreak of bloodshed awakens Moreau’s chimeras to the hypocrisy of the doctor’s dictates, causing them to rise up in rebellion.

Whether Prendick likes it or not, he is now in the same boat as Moreau, his associates, and the house chimeras. But the poison is in the wound. Moreau and his associates are killed by their creations. The compound burns down. Prendick is forced to live among the beastfolk, who revert evermore to their animal forms. They turn out to be—and the book dwells on this considerably—entirely incompetent at running the society Moreau leaves behind. Prendick eventually rafts out to sea, and in a second miraculous turn of fate is picked up by another ship, which returns him to his native England. Back in imperial London, he can’t help but see the beastfolk in the people that surround him.

There are layers to this plot. On the surface, it’s a gothic thriller about the humanity of animals and the animality of Man. Delve deeper and you find a story about scientific overreach: the great scientist, unbound by convention, unleashes unspeakable tragedy; the colonial gentleman who sees himself as the very pinnacle of civilization—indeed, on the cutting edge of evolution—turns out to be the most barbaric. However, this progressive interpretation doesn’t tell the whole story.

Like the book it may4 have partially inspired—Heart of Darkness by Joseph Conrad—Dr. Moreau critiques imperial folly while still suffering from it. To the extent that it can be read as a critique of imperialism, it is an entirely white-facing one. It follows a popular notion at the time: our attempts to civilize lesser beings are leading to our own degeneration. Conrad’s great work captures the bestial violence and hypocrisy of the white civilizing mission in the Congo while at the same time dehumanizing its subjects, portraying them as the grunting antithesis of civilization. Wells seems to do something very similar in Moreau, with a little roundabout trick. In this case, the “natives” are rendered as actual semi-animals.

Once you see this layer, it’s hard not to identify the contours of allegory. The doctor dressed in his white colonial suit, with his whip on the ready, experimenting on society as he pleases. His subjects arriving on the island courtesy of the naval arm of the empire. The new world where laws from the homeland no longer apply. The allegory becomes most clear in the laws Moreau draws on to mollify his creation (an obvious reference to the attempts to pacify colonized and enslaved people with the Bible); in the beastfolk’s quasi-anti-colonial uprising; and in their apparent inability to self-govern—a common colonial concern.

As if all that were too subtle, the protagonists in the novel regularly liken the beastfolk to other races. When Prendick runs into the first chimera, M’ling (who he later finds out is “a complex trophy of Moreau’s skill, a bear, tainted with dog and ox”), he literally thinks he’s meeting a Black person. “This man was of a moderate size, and with a black negroid face,” he says, unsettled. Another unlucky creature has a “face ovine in expression, like the coarser Hebrew type.” And so on. One may be tempted to read this as a commentary on the characters, as a portrayal of racism rather than embodiment of it, but Wells’ views on race tell us otherwise.

Writing about his dream of a world government in 1901, he pondered:

How will the new republic treat the inferior races? How will it deal with the black? How will it deal with the yellow man? How will it tackle that alleged termite in the civilized woodwork, the Jew? Certainly not as races at all. All over the world its roads, its standards, its laws, and its apparatus of control will run. This will make the multiplication of those who fall behind a certain standard of social efficiency unpleasant and difficult … The Jew will probably lose much of his particularism, intermarry with Gentiles, and cease to be a physically distinct element in human affairs in a century or so. But much of his moral tradition will, I hope, never die … And for the rest, those swarms of black, and brown, and dirty-white, and yellow people, who do not come into the new needs of efficiency? Well, the world is a world, not a charitable institution, and I take it they will have to go.5

This is the final screed of Conrad’s Kurtz (“exterminate all the brutes”) performed in a higher register. It was also, one must say, not an unusual position for a science-minded English gentleman of that period, all the way down to the genocidal philosemitism. In those circles, different races were commonly believed to be at different stages of evolution, somewhere on the continuum from animal to Christian white man. Accordingly, the above quote is not something Wells scribbled in his diary, but a paragraph he laid out in a multipart essay about his worldview. His defenders have cited many of his later writings to show how his views on race softened later in life, but for the book he wrote in 1896 the implications are clear. What are the beastfolk, after all, but an “inferior race” that have failed to develop “sane, vigorous, and distinctive personalities”?

By the end, The Island of Dr. Moreau points as much to the impossibility of civilizing the subhuman as it does to the inhumanity of the civilizers. Naturally, this comes with a fear of revenge. Wells’s next work, War of the Worlds, seems to follow very naturally from that: what if another race treated us the way we treated them? This question can sensitize a person to oppression. More often, as we can see acutely today, it has the opposite effect.

Of course, this now-unpalatable layer is probably not the reason why Moreau keeps getting readapted. It’s just a memorable plot by a canonical writer with lots of popular elements: animal-humans, moral intrigue, scientists playing God. In fact, the subtleties of Wells’s politics were the first thing to get lost when Hollywood started working its way through his catalog. The overtly racist bits would be spliced out of Moreau gradually, with every remake, just as they became publicly unacceptable. But can you really liberate a novel from its history? How did the bioethical paranoia and racism of The Island of Dr. Moreau fare in readaptations over a century?

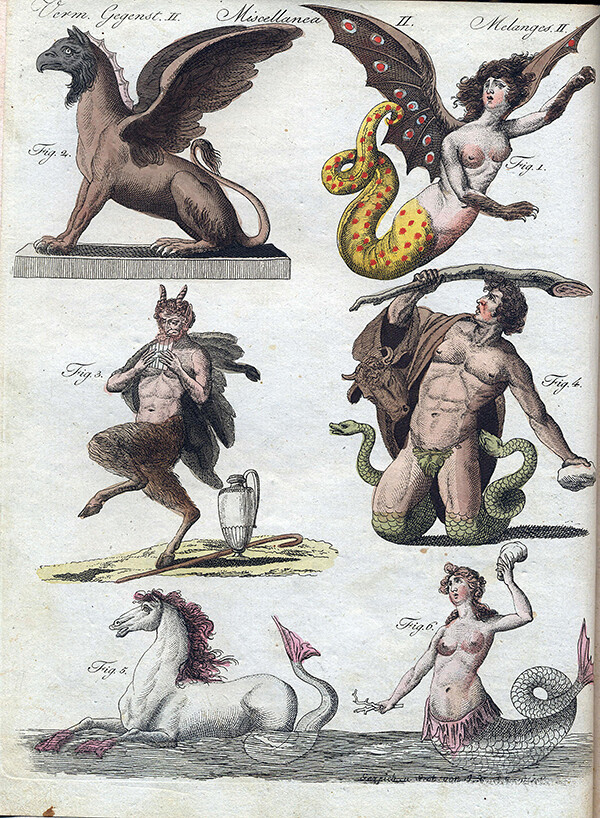

Friedrich Justin Bertuch, mythical creatures from Bilderbuch für Kinder (picture book for children), illustrated between 1790 and 1822. License: Public Domain.

The Trouble with Remakes

Watching all three major adaptations of Moreau in order, one witnesses what some biologists like to call “human-driven evolution.” Undesirable facets are grafted off and new desirable features (mostly sex and explosions) are added to allow the old thing to succeed on a new market. This process is mediated by a vast cultural supply chain. With American enthusiasm, innocence, and capital, generations of producers, writers, and directors simplify and amplify the colonial tale, trying to calibrate it to the fears, lusts, and sensitivities of successive generations.

Paramount’s Island of Lost Souls (1932), the first cinematic adaptation of the novel, directed by Erle C. Kenton, is a paramount example of this process. It brings to mind Eddie Izzard’s legendary bit about bombastic American remakes of quaint British films.6 Charles Laughton’s portrayal turns Moreau from an uncompromising man of science into a more or less total madman. His science has evolved with the times; he’s giving the animals plastic surgery while meddling with their “germ plasm.” Prendick has been given the requisite “my girl is waiting for me” backstory. He even dabbles in some unwitting bestiality, when Moreau tries to persuade him into procreating with the Panther Woman. The crescendo of the book—the beastfolk overthrowing Moreau—becomes the end of the film, and is enhanced with a walk-away-from-explosion tableau worthy of a Marvel movie. The second half of the novel—where the beastfolk run their society into the ground—is wisely cut altogether.

The new manic Moreau evokes early Hitler. But this was long before the Nazis’ race science reached its genocidal conclusion, or any of its lessons could sink in. Largely inured to the kind of bigotry presented in the novel, the makers reproduce it faithfully. Accordingly, the beastfolk’s looks align with race-based morphologies. The actors seem to have been cast with an eye for supposedly primitive phrenological features like low foreheads and wide jaws. Where Wells’s speculations had been guided by his mentor Thomas Huxley, Paramount recruited Thomas’s son, Julien Huxley, a famous eugenicist, to make sure the science was on point.

Dressed like a colonial officer, Moreau boasts that he acquired his techniques of population control in Australia. Our narrator, renamed Parker, is also a creature of Empire. “Strange-looking natives you have here,” he says upon arrival. The Panther Woman (a bulked-up and racialized version of a bit character from the novel, the Puma Woman) is introduced by Moreau as “a pure Polynesian,” a background Parker apparently finds alluring. This is late-Empire leisure chic, with all its tropes of palm fronds and exotic temptresses. Despite combining two then-popular forms, the horror flick and the minstrel show, The Island of Lost Souls bombed at the box office and disgusted critics. It would serve as a warning to future interpreters, but also as inspiration. Its plot updates would be picked up by all future Moreau reboots, which are as much corrective remakes of the first film as adaptations of the novel.

Don Taylor’s 1977 attempt is widely considered the best adaptation, though one might remark that it’s just the one that takes the fewest risks. This is a calm, picturesque, almost nostalgic Moreau. Its slow pace and handsome cinematography evoke the spaghetti Westerns of the period. The film is set in the 1890s and our hero (Michael York) is a perfect Edwardian gentleman. Burt Lancaster is the kind of Moreau envisioned by Wells: handsome, urbane, intellectual to the point of cruelty. He is a great man of science with only a touch of mania. “If one wants to study Nature, one must become as remorseless as Nature,” he proclaims.

Strangely, his knowledge of genetics is contemporary to the 1970s, as are the cultural attitudes of the film. By then, social Darwinism was more popular than the theory of evolution, and eugenic ideas remained polite conversation across the silent majority. On the other end of the political spectrum, a generation of activists had wised up to the relationship between science and the military-industrial complex. With these culture wars in mind, perhaps, this Moreau hedges its bets. By fleeing into the past, it manages to speak to contemporary concerns while avoiding all contemporaneous debates. It accomplishes this also by casting off many of the racial motifs of the original. The drastic improvement in film makeup allowed for the creation of manimals that look both very human and very animal—that Star Trek alien look. Characterologically, however, these are the most “human” beastfolk we get to see among the three films. Many of the chimeras—most notably, Richard Basehart’s unforgettable Sayer of the Law7—just seem like hairy, confused, simple, but ultimately decent people. Their efforts to become “civilized” are deeply moving—their disappointment when Moreau’s hypocrisy reveals itself, painful to watch. Ironically, this humanizing approach has the side effect of making the colonial overtones of the story more obvious. Parts of the beastfolk’s rebellion are shot to look like a political protest.

The Panther Lady, however, remains Polynesian. Our open-minded narrator falls for her not knowing she’s part animal, and what is merely hinted at in the 1932 film is consummated on camera. This being the late seventies, the interspecies liaison is shown to be tastefully erotic. Moreau himself insinuates that he has had relations with Panther Woman after plucking her from her native island, combining sex tourism and animal research. And yes, this is The Island of Dr. Moreau at its most subtle.

The same cannot be said of the universally panned 1996 adaptation, which isn’t only the weirdest Moreau, but probably one of the most galaxy-brained features ever greenlit. Jampacked with over- and underacting, counterintuitive plot innovations, unnecessary gore, and hilariously extra-aesthetic choices, this centennial adaptation would go down as one of the worst films of its era.

If Hollywood’s third swing at Moreau would establish The Island as cursed material, this has a lot to do with the chaotic way it was made. Eccentric director Richard Stanley (a weird British cowboy stoner) was such a fan of Wells’s novel—so amused by the 1932 version and so bored by the 1977 remake—that he invested a big chunk of his life in finally getting it right. He spent four years working on a script: a wild, subversive Moreau for the nineties. But after acquiring the project, New Line Cinemas quickly tried to replace him with Roman Polanski(!). Stanley survived this coup by back-channeling with Marlon Brando, the studio’s desired Moreau. Explaining the novel’s complicated history in impressive detail (and hiring a voodoo priest to sway Brando), Stanley convinced the old contrarian that only he could do the job.

More good news followed. Bruce Willis signed on to play Prendick. But that’s when the alleged curse started to take hold. Demi Moore left Bruce Willis and America’s most broken action hero dropped out. The famously impossible Val Kilmer signed on to replace him under the condition that his shooting hours be reduced by 40 percent, leaving just enough time for him to play Moreau’s sidekick, Montgomery. Brando’s daughter committed suicide and the actor took a leave of absence from the set. The studio jumped at this second opportunity and replaced Stanley with the more experienced John Frankenheimer (The Manchurian Candidate, French Connection II). In the ultimate meta-narrative, Stanley fled the compound. Staking out in the woods, smoking inordinate amounts of weed, getting increasingly paranoid, he started building IEDs to attack the set from outside. The production would go down as the most toxic set in Hollywood history.

This arrangement partially accounts for the almost frightening disjointedness that ended up on screen. Everyone in this Moreau—and indeed, behind the camera—seems like they’re either on tons of uppers, tons of downers, or an unstable combination of the two. The trippy aesthetic is perhaps best described as a Nine Inch Nails–inflected Donkey Kong, or like if Chris Cunningham directed an episode of Lost. By the time we meet the Panther Woman, henna-tattooed and dancing to ethnotronica from a Discman, we’re waist-deep in the nineties.

Brando’s decidedly drowsy Moreau is a giant, pasty blob who is allergic to the sun and gets his minions to carry him on a curtained litter. Depressed, perverted, neurotic, solemnly proud of his subjects, he is more of a fallen hero than a villain. This creates a weird dynamic with his counterpart, the shipwrecked narrator, played by the acerbic David Thewlis, who somehow manages to come across as the more unstable and unlikable of the two. A horny British do-gooder—a UN negotiator, shipwrecked on his way to negotiate a “peace settlement”—Prendick spends the first half of the film in frankly disrespectful contempt of the beastfolk, which at times makes him seem rude and ableist. He is disgusted by their appearance and expresses his outrage about their creation in strangely Christian tones. He is every bit as colonial as Moreau. Wired to maximum intensity, Kilmer’s Montgomery is an academic in nineties alt-hunk disguise, sort of like a biotech Tyler Durden. How exactly he and Moreau combine humans and animals is ill-defined, except that it involves microinjecting human plasmids into their cells. Montgomery administers a complimentary psychedelic cocktail to the chimeras just for kicks. Despite these scientific advances, most of the beastfolk in the film—aside from Moreau’s perfect Panther Girl, played by the tweaky and ethnically ambiguous Fairuza Balk—have devolved from the humanizing seventies remake. They are deformed in all shapes and sizes—experiments that didn’t quite work out. The ferocious leopard man and hyena swine look perpetually haggard and slumped over.

In the best and worst nineties way, this Moreau is all affect. Things happen because they’re crazy, wild, intense, dark. Even the doctor’s eugenics talking points and chimera-pope ceremonies just seem like provocative meta-jokes. Decontextualized from everything, the colonial attitudes of the original persist only as subtext—a structural bias baked deep into the plot—perhaps only ascertainable to the kind of people who are sensitive to that sort of thing for professional or historical reasons.

The bioethical paranoia, meanwhile, has been dumbed down into nineties stoner attitudes. It seems to say: The world is a fucked-up place. Scientists are psycho. Don’t mess with nature—all those nineteenth-century hangovers reinterpreted at the end of history. The specific fears of the original are rendered general, reflecting whatever biological practice triggers a collective gag reflex today. We still get strong hits of Wells’s proto-Christian concern with scientists playing God and his fixation with degeneration. In this way, classic sci-fi novels can behave a bit like conspiracy theories. With every movie directly or indirectly inspired by Dr. Moreau, the fears and follies of late-nineteenth-century Europeans are recycled for a new generation. What is the cumulative effect of all this inherited paranoia? And what does it mean for those of us working in science and science fiction?

Re-Animator, directed by Stuart Gordon, 1985 (film still).

Bursts of Bioethical Conservatism

Sociologists have long tried their best to measure the impact of popular sci-fi on public attitudes. Though methodologically tricky, the consensus seems to be that the genre informs lay people’s feelings about science more profoundly than anything they learn in school. While sci-fi is often lauded for inspiring scientific innovation, it has arguably inspired more fear of science. Starting in the mid-1990s, this fear has been directed increasingly at biotech.

In 2013, a team of Austrian sociologists analyzed forty-eight sci-fi blockbusters that deal with “synthetic biology-relevant aspects and ideas” to identify how they “influence the public awareness and understanding” of the field.8 Research in these films, they find, is often being conducted in the shadows; motivations are often initially understandable (or even humanitarian) but deformed by ambition. The culprits are either independent researchers, rogue employees of a company conducting their research in secret, loyal employees openly carrying out sanctioned (though controversial) research, or corporate or governmental entities conducting secret experiments. They can be plotted on a spectrum from deranged loners (Herbert West in Re-Animator) to urbane extroverts (Seth Brundle in The Fly), while the corporations are on a continuum from naive (InGen in Jurassic Park) to sinister (Umbrella Corp in Resident Evil). The old themes of Promethean hubris and devil’s bargains are still present, but modified by the migration of scientific research from the academy into the private sector. The results generally threaten humanity.

Thematically and aesthetically, at least, today’s popular anti-science conspiracy theories seem heavily influenced by these dystopian blockbusters about biotech. The lab-leak theory of Covid-19’s origins, for example, is so dynamic a story that it manages to encompass all of the archetypes mentioned in the above study. The mainstream incarnation of the theory speculates about naive and reckless gain-of-function researchers accidentally unleashing Covid-19 on the general population. The fringier version sees a sinister plan by demonic scientists and pedophile elites to spread a novel coronavirus in a roundabout effort to microchip the global population and establish—Wells’s great dream—a world government. Some polls have shown this alternative explanation to be more popular than the official narrative about Covid-19.9

This is not to blame popular sci-fi for the now-endemic suspicions of science. Certainly, the long history of atrocious experiments committed in the name of biology and chemistry—along with sociocultural factors like underfunded education, religious bioconservatism, and political polarization—have contributed to this paranoid view of innovation. It’s merely to say that the strain of Manichean sci-fi brought into the world by stories like The Island of Dr. Moreau has helped limit our dystopian imagination. This responsibility is worth beholding, particularly by those working to continue this troubled lineage.

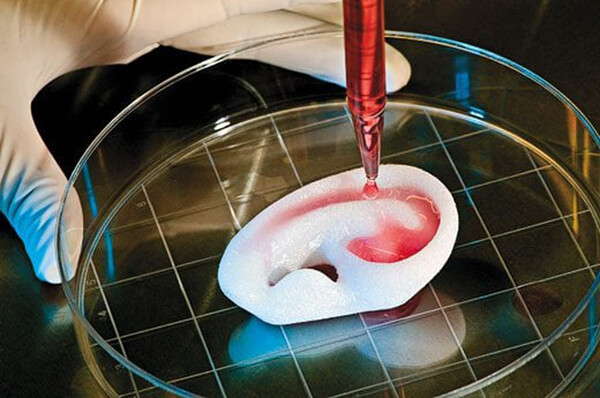

Regenerating a human ear using a scaffold. License: CC BY 2.0.

The Modular Body is an online science fiction story about the creation of OSCAR, a living organism built from human cells. Courtesy Floris Kaayk, 2016.

Regenerating a human ear using a scaffold. License: CC BY 2.0.

Notes for Future Adapters of Dr. Moreau

Unfortunately, it is inherent to the way movies are churned out in Hollywood that—to paraphrase Dr. Ian Malcolm—whether you can make a film matters a lot more than whether you should. This applies particularly to readaptations of popular novels. The Island of Doctor Moreau keeps getting remade because it’s been remade before. People know the story already, whether directly or indirectly, and to Hollywood producers that suggests a certain level of interest. In this case, however, the should we? question deserves particular emphasis. If you have to scrub many of the major elements of an old novel to turn it into a viable film, perhaps you shouldn’t remake it at all.

And yet, the temptation is perfectly understandable. The plot is very exciting. It takes us right to the heart of our scientific paranoia, our inner conflict over where the corruption of nature begins. The very fact that it hasn’t been done well, but that even the two worst Moreaus are cult favorites, adds to the luster of the challenge. What’s more, the central innovation predicted by the book—a technology that can finally combine animal and man—only seems more plausible with time. The monkey-human embryos that were created and dashed in late 2020 suggest a vast range of future possibilities. These chimeras could become organ donors. They could perform jobs people don’t want to do. They could fight our endless wars. All of this remains far beyond current capabilities and anathema to even the most permissive interpretation of bioethics. But in the current climate of paranoia—where many people seem willing to believe almost anything about each other, not to mention politicians and scientists—it seems a profitable area of speculation for dystopian blockbusters.

The latest prospective remakers certainly seem to think so. Talking to Deadline in late 2020 about his work on the forthcoming Moreau remake, screenwriter Zack Stentz said that now feels like “the perfect time to bring Moreau into our own 21st Century world of transgenic animals, designer babies and other scientific advances Wells never could have dreamed of.”10 Completely apart from the fact that Wells did literally dream of all these things, one can only assume that the team working on this remake has struggled to grasp what kind of material they have on their hands here. No news has dropped about the production recently,11 so perhaps they’re still on that path—stranded somewhere among that long lineage of Hollywood talent. The supposed curse they’re facing, we humbly suggest, is just an abundance of irreconcilable history. It’s just very hard to whitewash this kind of material without losing it altogether.

CRISPR (clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats) is a family of DNA sequences found in the genomes of prokaryotic organisms. CRISPR-Cas9 is a specific protein in bacteria that can be used as a gene-editing technology to cut out specific parts of a cell’s DNA and replace them with new sequences. See → and →.

James White, “Ready For an Island of Doctor Moreau TV Series?,” Empire, December 11, 2020 →.

Quoted in Roger Luckhurst, “An Introduction to The Island of Dr. Moreau: Science, Sensation and Degeneration,” The British Library, May 15, 2014 →.

Wells certainly thought so. There are notable similarities to the texts. And there is evidence that Conrad had read Moreau while working on Heart of Darkness, which came out a year later.

H. G. Wells, Anticipations of the Reaction of Mechanical and Scientific Progress upon Human Life and Thought (Chapman & Hall, 1902).

See →.

See →.

Angela Meyer et al, “Frankenstein 2.0.: Identifying and Characterising Synthetic Biology Engineers in Science Fiction Films,” Life Sciences Society and Policy 9, no. 9 (October 2013).

For example, see Alice Miranda Ollstein, “POLITICO-Harvard poll: Most Americans Believe Covid Leaked from Lab,” Politico, July 9, 2021 →.

Quoted in White, “Ready For an Island of Doctor Moreau TV Series?”

Though a three-year turnaround isn’t unusual for a Gunpowder & Sky project.