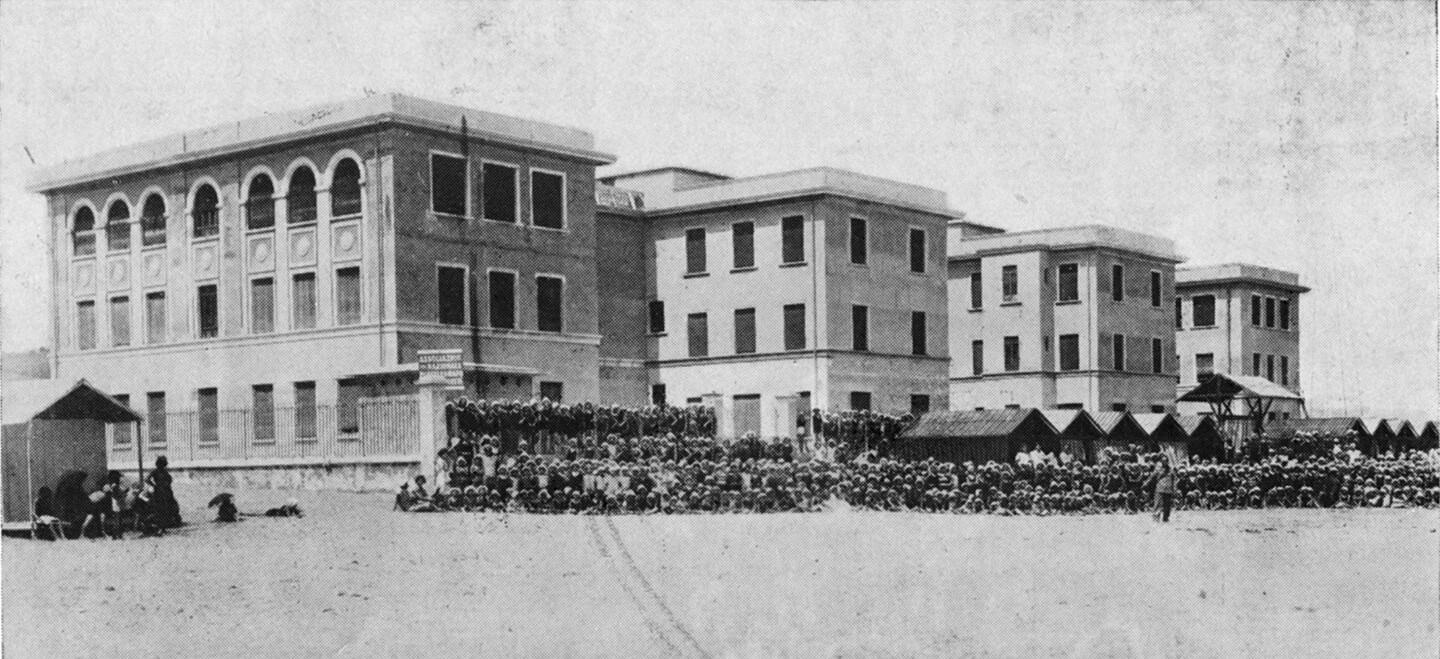

Breakfast: a quarter of a liter of milk and coffee accompanied by “bread galore.” Lunch and dinner: a minimum of ninety grams of pasta, followed by one hundred grams of meat or fish, fruit, and a dessert. As specified in the first report of the colony of Villa Marina XXVIII Ottobre, published in October 1932, all the meals at this fascist youth colony had to be of “the finest quality and strictly controlled.”1 Every summer, the proletarian children would arrive in Pesaro, a small town in central Italy, on trains organized from every corner of the country by the National Fascist Party. They were welcomed by the local Fascist authorities and organizations before starting their regimen, including sun and sea therapies in addition to their strict diet.

In short, the youth were subjected to strict hygienic-sanitary scrutiny. Every morning, the colony doctors monitored the cases of weak or sick children. “No deaths this year,” reads the 1932 report. To wrap up the pedagogical and edifying routine, every evening, at sunset, the children were assembled in the main square in front of a large rationalist building and asked to sing fascist and nationalist songs.

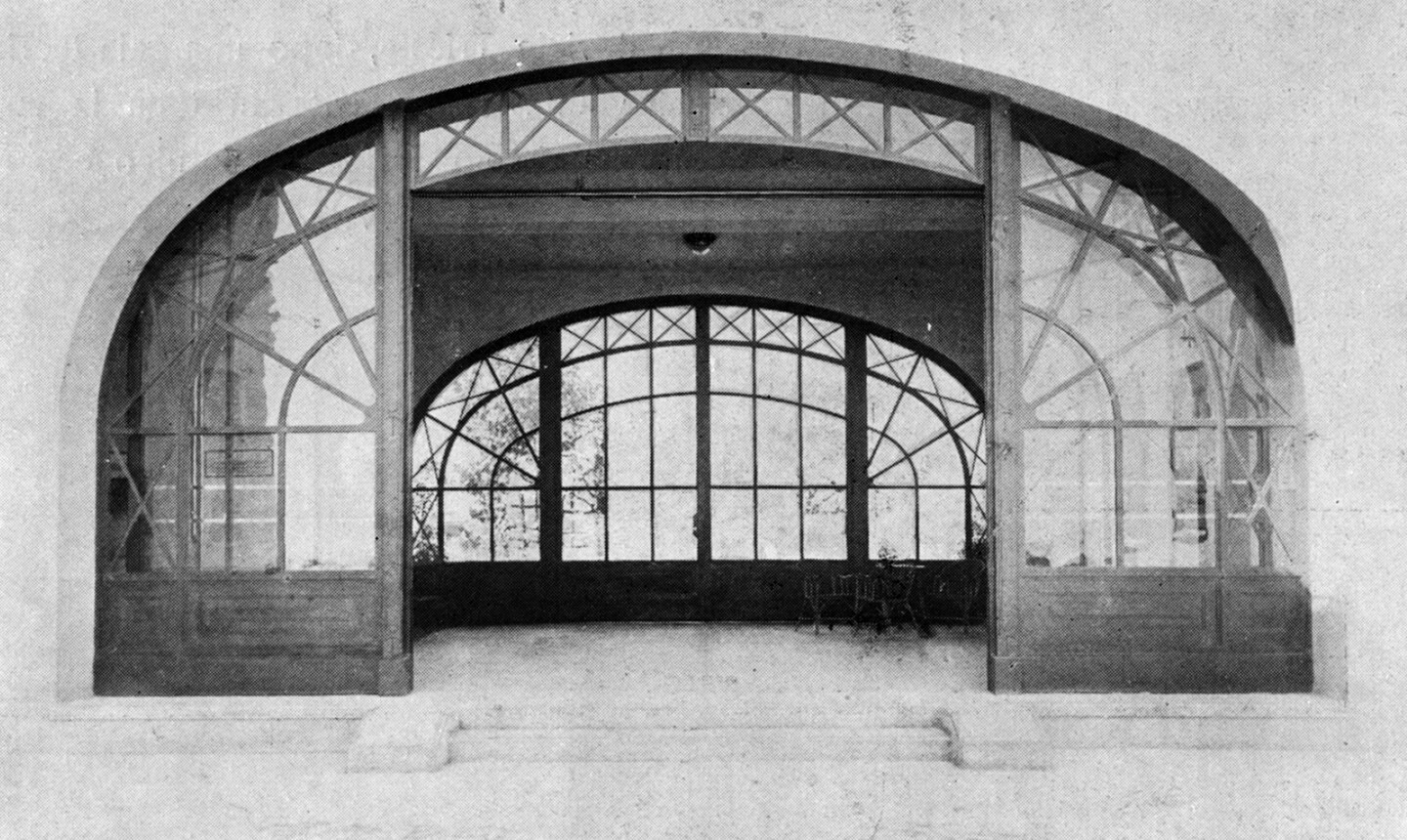

The Refectory (capable of hosting 500 people) of the Villa Marina colony, Pesaro. Source: Istituto di Assicurazione e Previdenza per i Postelegrafonici (1932), Villa Marina XXVIII Ottobre Pesaro. Estate MCMXXXII A. X.

Benito Mussolini sent a message to celebrate the inauguration of the colony in 1928, dedicating it “to the sons of the Italian post and telegraph workers.” The colony was named after the infamous March on Rome of October 28, 1922, when the National Fascist Party organized a massive demonstration in the Italian capital, leading to Mussolini’s eventual coup d’état. Pesaro’s youth colony was erected a few years later on one of the main beaches of our hometown, on the Adriatic coast. The huge rationalist construction was part of a system of more than two hundred similar institutions built on Italian seashores during the fascist period. They were meant to provide the sons of the Italian proletariat with a summer holiday of “climatic care,” strengthening the bodies and souls of the “Italian race.”2

As part of an extended research project about the youth colonies, we visited the crumbling building during the summer of 2021. At first, we did not imagine that many of the official documents related to the fascist past of Pesaro’s colony had been lost.3 It took us a few months but we finally started to make some initial discoveries, connecting the scattered written and visual fragments available online, in local libraries, and in personal archives. We managed to access the above-mentioned 1932 report with the help of a man who was part of the Pesaro section of the Communist party (PCI). As part of his political activism, Luciano Trebbi dedicated his life to collecting objects and publications from the fascist period to keep the memory of the Italian partisan resistance alive. He drove us to a local printing studio that had scanned the original copy of the report. “This document should be printed and distributed widely to the local population. We should never forget the history of these institutions,” Luciano told us. He then asked: “Can you print 1,300 copies and distribute them to the local population through your project?”

Villa Marina colony, view from the beach, Pesaro, 1932. Source: Istituto di Assicurazione e Previdenza per i Postelegrafonici (1932), Villa Marina XXVIII Ottobre Pesaro. Estate MCMXXXII A. X.

Main Entrance, Villa Marina colony, Pesaro, 1932. Source: Istituto di Assicurazione e Previdenza per i Postelegrafonici (1932), Villa Marina XXVIII Ottobre Pesaro. Estate MCMXXXII A. X.

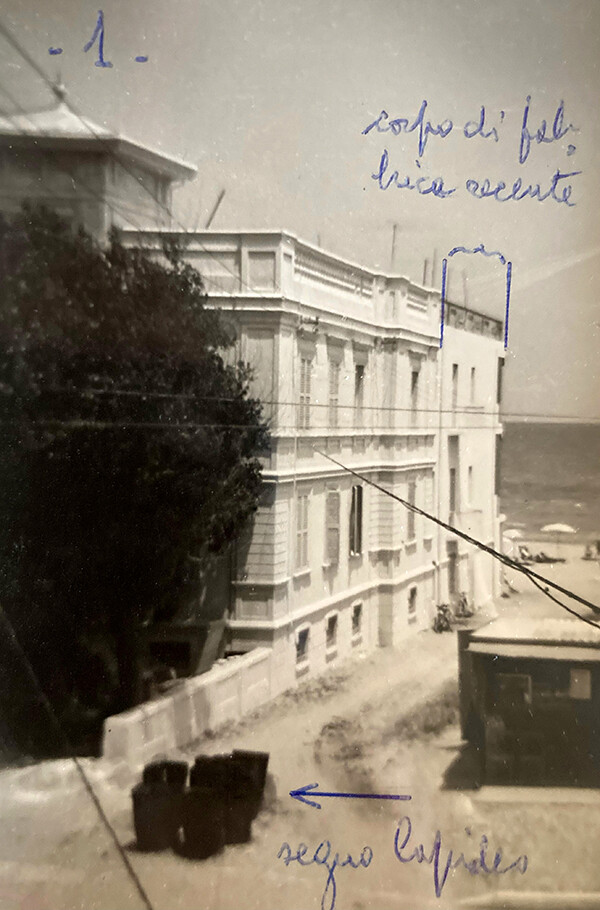

Main Entrance, Villa Marina colony, Pesaro, 2021. Photo: Tommaso Fiscaletti and Nicola Perugini.

Villa Marina colony, view from the beach, Pesaro, 1932. Source: Istituto di Assicurazione e Previdenza per i Postelegrafonici (1932), Villa Marina XXVIII Ottobre Pesaro. Estate MCMXXXII A. X.

During the final years before the fall of fascism, the colony of Villa Marina became the local headquarter of the Nazi occupying forces. The building was the last eastern bastion of the Gothic Line, the fortification shield created by the Nazis in order to fight the Allied forces and the Italian partisans. The Allies bombed the colony and, with the support of the local resistance, liberated Pesaro. A year ago, one of us was going through our family archives and found a photo that belonged to one of our grandparents. It showed the aftermath of the renovation of the colony, after Italy’s liberation. The relative was a member of the National Fascist Party and later, after the fall of the regime, he participated in the restoration of the colony.

Villa Marina Colony, Pesaro, 1961. Source: Perugini Family Archive.

Fascist Heritage

These dispersed archival objects allow us to rediscover Villa Marina and its post-fascist afterlife. After World War II, the colony became a space administered according to new democratic principles. However, its summer camp functions remained somewhat similar: children of post and telegraph workers continued to be hosted every summer on Pesaro’s seashore in the renovated colony, until the end of the last millennium. They continued to enjoy the sunbathing therapy instituted by the fascists. They continued to remain confined and monitored. Their weight and health conditions were systematically checked.

But their daily education was sanitized of any aspects of fascist and nationalist indoctrination. The memory of the fascist past of the building in which they spent their summer fell into oblivion, even as it haunted the complex.

Facade on the beach side, Villa Marina Colony, Pesaro, 2021. Photo: Tommaso Fiscaletti and Nicola Perugini.

At the beginning of the twenty-first century, the building was abandoned and started to deteriorate. The Pesaro municipality scaffolded the colony building and sealed its doors and windows with concrete to protect the decaying structure. The local authorities wrapped it in white cloth, giving it a spectral, ghostly aspect. In so doing, the history of the colony was thrown further into obscurity and forgotten memory. Its haunted aspect was bolstered by local newspapers often referring to it as the “ghost building.” In 2018, less than a century after Mussolini came to power, there was one last coup de théâtre. The Italian Ministry of Cultural Preservation and Tourism included the fascist colony in its list of national cultural heritage sites, publishing a long report in which it defined Villa Marina as a building of “cultural interest” subject to preservation.4

According to the ministry’s description, the colony was designed “not only for therapeutic goals, but also for those of education and propaganda.” It had to be “welcoming and reassuring in order to leave an indelible trace in the mind of the Italian youth” and create fascist political consensus. The summer colonies, the ministerial report concludes, were among the “most successful” institutions created with these goals by the fascist regime.5

The research we are conducting and the archive we are assembling about the summer colony are specifically aimed at interrogating the fascist heritage that the ministry wants to preserve in a watered-down way. We hope the material we are gathering can serve as a counter-archive to official, institutional, whitewashed memory. In particular, we are spurred into action by the fact that our hometown was recently nominated to be the Italian Capital of Culture 2024, opening a new opportunity for civic initiatives that would either expose the past or relegate it to being forgotten or rewritten.6

Decolonizing the Colony

Completely absent from the report by the Italian Ministry of Cultural Preservation and Tourism, which focuses on the technical and bureaucratic aspects of the conservation of the architectural features of the building, is a critical understanding of how Villa Marina XXVIII Ottobre and the myriad summer youth colonies situated on Italy’s seashores played an important role in the fascist regime’s policies of colonial and imperial expansion. The architecture of the building cannot be separated from the broader international political architecture it embodies.

After we discovered a “Manual for the Directors and Assistants of the Climatic Colonies,” the intimate relationship between “internal colonialism”—the construction of youth colonies on Italian national soil—and the regime’s colonial plan of overseas racial domination in Northern and Eastern Africa became much clearer. Published in 1935 by the National Fascist Party, while Italy was invading Ethiopia, the manual describes the goal of the youth colonies as one of preservation of the “bodily and moral health” of Italian children. The youth had to be subjected to a process of “hygienic propaganda and moral elevation.” According to the fascist manual, the summer camps represented a symbol of “Italian genius” and were a fundamental tool for “containing the decline of [the Italian] race.”7 In other words, the fascist renovation of the “Italian race” in the homeland’s summer colonies went hand in hand with the extension of Italy’s racialized domination in the fascist empire in Africa.

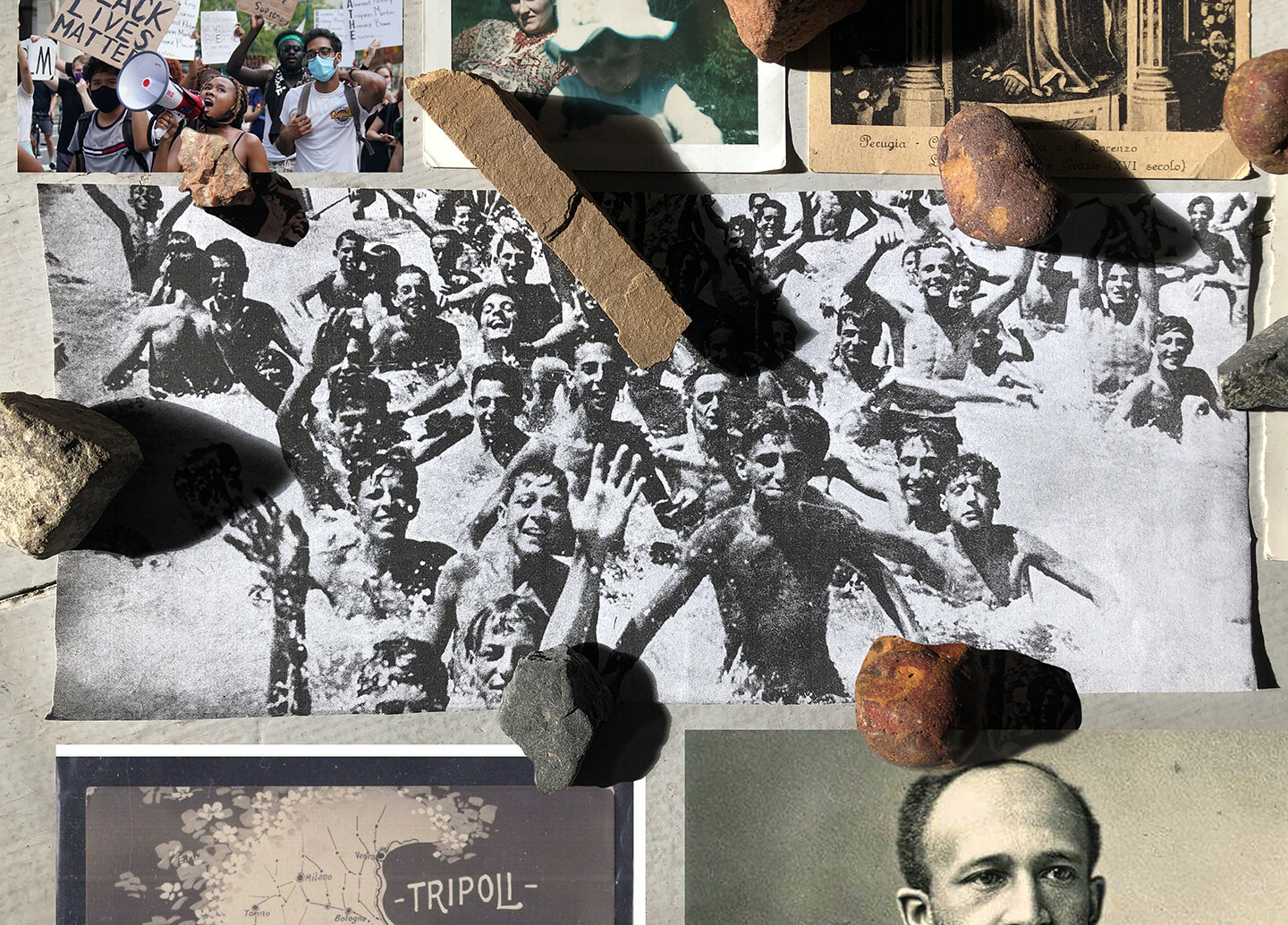

This connection between internal and overseas colonialism became even more obvious to us when we found an old copy of the fascist magazine Il Legionario (“The Legionnaire,” named for the Roman soldiers of antiquity). The magazine’s cover portrays a group of joyful boys playing at the seaside. The image creates a sense of familiarity for viewers—especially those who live near the sea—while revealing something unexpected. In fact, the boys are the sons of Italian settlers from Libya hosted in one of the Adriatic summer colonies. In 1940, the fascist regime transported thirteen thousand Italian children from Libya across the Mediterranean—that very sea that has become a huge cemetery of nonwhite migrants in recent decades—to the Adriatic summer colonies to “rediscover their homeland” and train their bodies and souls in order to become future imperial conquerors in Africa. “Hurray Italy! Hurray the Duce! Hurray Hitler! Hurray the Empire!” the Italo-Libyan children were forced to sing in the Adriatic heliotherapic structures.8

Digital mockups by Tommaso Fiscaletti and Nicola Perugini, Studio for Installation #1 (billboard), 2022.

The political and cultural question at stake with the summer colonies does not merely concern how to understand, challenge, and reuse the fascist architectural structures of the colonies—a question that has generated an important debate in Italy in recent years.9 It is also imperative to understand the racialized and colonial nature of these institutions that constituted a pillar of the fascist regime’s “biological policy” and how their colonial and imperial history persists in our present. Of course, this becomes yet more urgent today after neofascist political forces gained a parliamentary majority in the September 2022 Italian national elections. Understanding the realities of the past has become an acutely important task for building anti-fascist movements in the present. Just as Luciano, the Resistance fighter we met, understood the necessity to not forget past struggles, we must also emphasize the continuation of colonial and racist programs in the present to better combat them.

A major question for present-day Italians is what it means to decolonize our internal colonies, in light of their deep connection to Italy’s fascist expansionism overseas. This expansionism played a role in the constitution of forms of transnational anti-racist solidarity that have inspired current global struggles to defend people of color and others against attacks by white-supremacist power. In the words of W. E. B. Du Bois in his article on the Second Italo-Ethiopian War, the resistance to Italy’s attempts to subject Ethiopia to its racialized order was a cornerstone in the process of the international formation of a new Black consciousness:

Black men and brown men have indeed been aroused as seldom before. Mass meetings and attempts to recruit volunteers have taken place in Harlem. In the West Indies and West Africa, despite the efforts of both France and England, there is widespread and increasing interest. If there were any chance effectively to recruit men, money, and machines of war among the one hundred millions of Africans outside of Ethiopia, the result would be enormous. The Union of South Africa is alarmed, and in contradictory ways. She is against Italian aggression not because she is for the black Ethiopians, but because she fears the influence of war on her particular section of black Africa. Should the conflict be prolonged, the natives of Kenya, Uganda, and the Sudan, standing next to the theater of war, will have to be kept by force from joining in. The black world knows this is the last great effort of white Europe to secure the subjection of black men. In the long run the effort is vain and black men know it.10

The fascist summer youth colonies must be rediscovered as key sites of the production of Italy’s racial identity, playing an important role in fueling Italy’s colonial aggressions against the nonwhite world. Though some Italians might think that they are living in a post-fascist Italy, internal colonies must still be liberated and decolonized. The scope of our research is to help trigger this process, inviting readers and viewers to understand and participate in anti-racist struggles of the present.

Villa Marina Colony, Pesaro,Studio for the Installation #1 (billboard), 2022. Digital Layout of the final photograph. Tommaso Fiscaletti and Nicola Perugini.

Istituto di Assicurazione e Previdenza per i Postelegrafonici, “Villa Marina XXVIII Ottobre” (Estate MCMXXXII A. X., 2013), 21.

On the summer colonies as a pedagogical project, see Colonie per l’infanzia nel ventennio fascista: Un progetto di pedagogia di regime, ed. Roberta Mira and Simona Salustri (Longo 2019); and Francesca Franchilli, Colonie per l’infanzia tra le due guerre. Storia e tecnica. Ediz. illustrata Colonie per l’infanzia tra le due guerre. Storia e tecnica (Maggioli Editore, 2009).

After the end of World War II many official fascist documents disappeared for a number of different reasons. In certain cases, they were destroyed as the result of Allied bombardment. In other instances, they were kept hidden by the postwar Italian authorities to protect the identity of fascist functionaries and supporters, or to protect the documents themselves from destruction. Some of them are still hidden and one of our objectives is to explore local state archives to search for traces of the colony during the fascist era.

Ministero per i Beni e le Attività Culturali e del Turismo, Commissione Regionale per il Patrimonio Culturale, “Ex convitto Villa Marina. Relazione Storico Artistica Architettonica,” 2018, 2.

“Ex convitto Villa Marina,” 4–5.

Every year the Italian Ministry of Culture nominates a national capital of culture. The designated town or city receives funds from the ministry in order to showcase its cultural heritage and development, usually spawning cultural events, exhibitions, and so on.

Partito Nazionale Fascista, Lezioni tenute al corso per direttrici ed assistenti di colonie climatiche (Torino: Tipografia Barattini 1935).

Anna Arnese Grimaldi, I tredicimila ragazzi italo-libici dimenticati dalla storia (Savona: Marco Sabelli Editore, 2014), 52.

See Ruth Ben-Ghiath, “Why Are So Many Fascist Monuments Standing in Italy?,” The New Yorker, October 5, 2017; Igiaba Scego, Roma negata: Percorsi postcoloniali nella città (Roma: Ediesse 2014); and Emilio Distretti and Alessandro Petti, “The Afterlife of Fascist Colonial Architecture: A Critical Manifesto,” Future Anterior 16, no. 2 (2019).

W. E. B. Du Bois, “Inter-Racial Implications of the Ethiopian Crisis. A Negro View,” Foreign Affairs, October 1935.

This essay was written as part of a larger project on the fascist summer colonies. The written and visual fragments of memory we are accumulating will be exhibited to the citizens of Pesaro in the form of a public installation, made with the support of the local municipality. Our objective is to “reawaken” the colony in the coming two years, leading up to the city becoming the Italian capital of culture. The aim of the project is to interrogate the relationships between the heliotherapic structure of Villa Marina XXVIII Ottobre, the history of Italian colonialism, and their relevance to contemporary anti-racist struggles. The project will ultimately unfold into a series of multimedia works and public interventions.