To the memory of Leo Bersani

In March 2022, a friend who has assiduously avoided indoor restaurant dining for two years—her elderly mother is immunocompromised—drove to an academic conference in Indiana, where she ended up, unmasked, eating inside a restaurant (“it was more like a sports bar”) with a group of conference-goers. She tells me this tale in a tone of horrified glee. When I inquire further about the experience, she likens her otherwise unremarkable dinner to “being at an orgy.” “Next thing you know,” I suggest, “you’re barebacking in restaurants.” “Exactly!” she replies. The group dining that punctuates academic conferences—and, indeed, constitutes one of their greatest pleasures—suddenly feels like group sex. Taking off your mask to dine in a restaurant with people you’ve just met is like dispensing with the condom when having sex with strangers. All bets are off, the usual precautions suspended, as one experiences a pleasure that is intensified by one’s consciousness of risk. The notion of barebacking in restaurants offers a fantasy image, something that gives form to unexpected sensations of transgression in an ordinary public place.

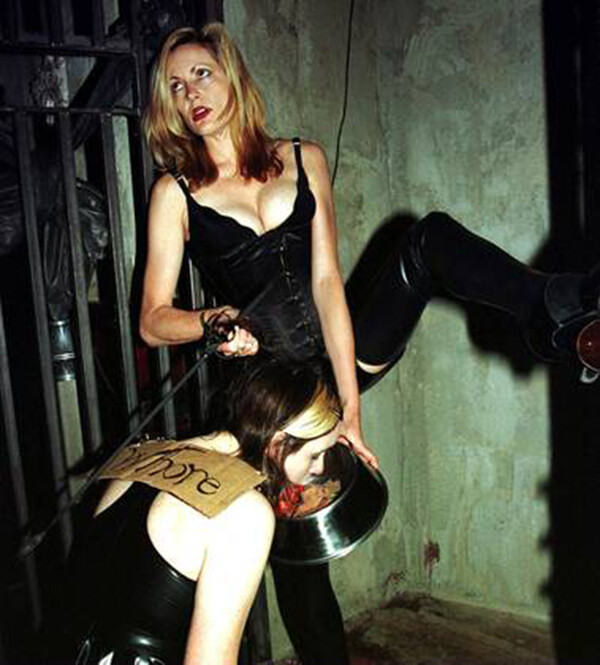

S&M restaurant La Nouvelle Justine in New York City

What made dinner at a Midwestern sports bar feel like “being at an orgy” was the presence—threatened or actual—of SARS-CoV-2. The supersaturated sociability of restaurant dining after the isolation of social distancing; the possibility of sharing food, air, and, hence, intimate exchange with a host of others; even the fact that, early in the pandemic, some referred to masks as “face condoms”: these elements all inform the phantasm of barebacking in restaurants. Here my concern is less the statistical risks of indoor dining from an epidemiological perspective (or the exhausting calculations they entail) than fantasies about risk. Viruses are an exemplary object of these fantasies. Many people have fantasies about viruses—and not merely ideas about them—because viruses so readily traverse what we imagine as our bodily borders. A virus may move from outside to inside “me” without my knowledge or control, thereby making evident how unself-contained “I” am; this is especially true of airborne viruses such as SARS-CoV-2. It is the virus as a sign of corporeal porosity or borderlessness that provokes paranoid fantasies of invasion, penetration, and foreign occupation. In testifying to the human body’s penetrability, a virus threatens to make bottoms of us all. Whatever else they do, viruses remind their human hosts of our species’ physical vulnerability: virality conjures the specter of human helplessness. These kinds of threats, imaginary and real, help to account for the extreme reactions we’ve witnessed during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Fantasy frequently functions as a defense against viral challenges to myths of bodily integrity and human exceptionalism. In my research on HIV/AIDS over the past thirty years, I have tried to make space for considering the suprarational ways that people think about viruses. It should come as no surprise that popular thinking about a disease regarded as sexually transmitted would be inflected by unconscious fantasies.1 What has been striking about responses to the Covid-19 pandemic is how prone virtually everyone appears to nonrational thinking about a virus whose modes of transmission have little to do with sex. Covid-19 laid bare not only the deteriorated condition of public health infrastructures, but also how virally intimate everyone is with the people around them, whether friends, neighbors, coworkers, or strangers. Fantasy responds to the discovery, or the reminder, that those folks can leave traces of themselves inside us more readily than we knew. This is viral intimacy without the pleasures of sex.

If viral fantasies are fueled by misinformation, they nevertheless cannot be dispelled simply by accurate (or more complete) data. The sciences of virology, immunology, and epidemiology, while crucial, remain insufficient in this context, because they cannot account for how most people actually think about the coronavirus. Indeed, the wish not to think about it—to imagine that the pandemic is a hoax, that it is already over, or that we can “go back to normal” any day now—is, from the point of view of psychoanalysis, just one more sign of unconscious thinking about this virus. The primary response to an unwelcome reality is to reject it. This is where fantasies about racial difference have played a particularly insidious role: designating SARS-CoV-2 as “the China virus” (as Trump and others did) promotes a fantasy that the epidemic may be curbed via border lockdowns, racial segregation, or anti-Asian violence. Needless to say, racializing a virus contains it in fantasy only: such fantasies generate real effects, just not the ones stipulated. As we insist that SARS-CoV-2 is not a Chinese virus, we might also acknowledge that the clarification isn’t enough to defuse the fantasy.

That gap between knowledge and fantasy is not an empty space waiting to be filled with greater or more refined knowledge. The cure for rampant misinformation can never be only reliable scientific information, vital though that is, because fantasies are not merely errors or illusions. Instead, fantasies are modes of thinking at the level of the unconscious that we ignore at our peril. For human subjects, fantasy is neither trivial, secondary, or irrational but, rather, constitutive of our psychic lives. And fantasies are not simply products of individual psychology but structure group mentalities at various scales; as critics from Jacqueline Rose to Slavoj Žižek have demonstrated, fantasies are eminently political.2 We think through our fantasies—and never more so than when confronting those pathogenic entities, invisible to the naked eye, that retain a capacity to enter our bodies seemingly at will.

An eighteenth century pornographic cartoon features Marie Antoinette and Lafayette. License: public domain.

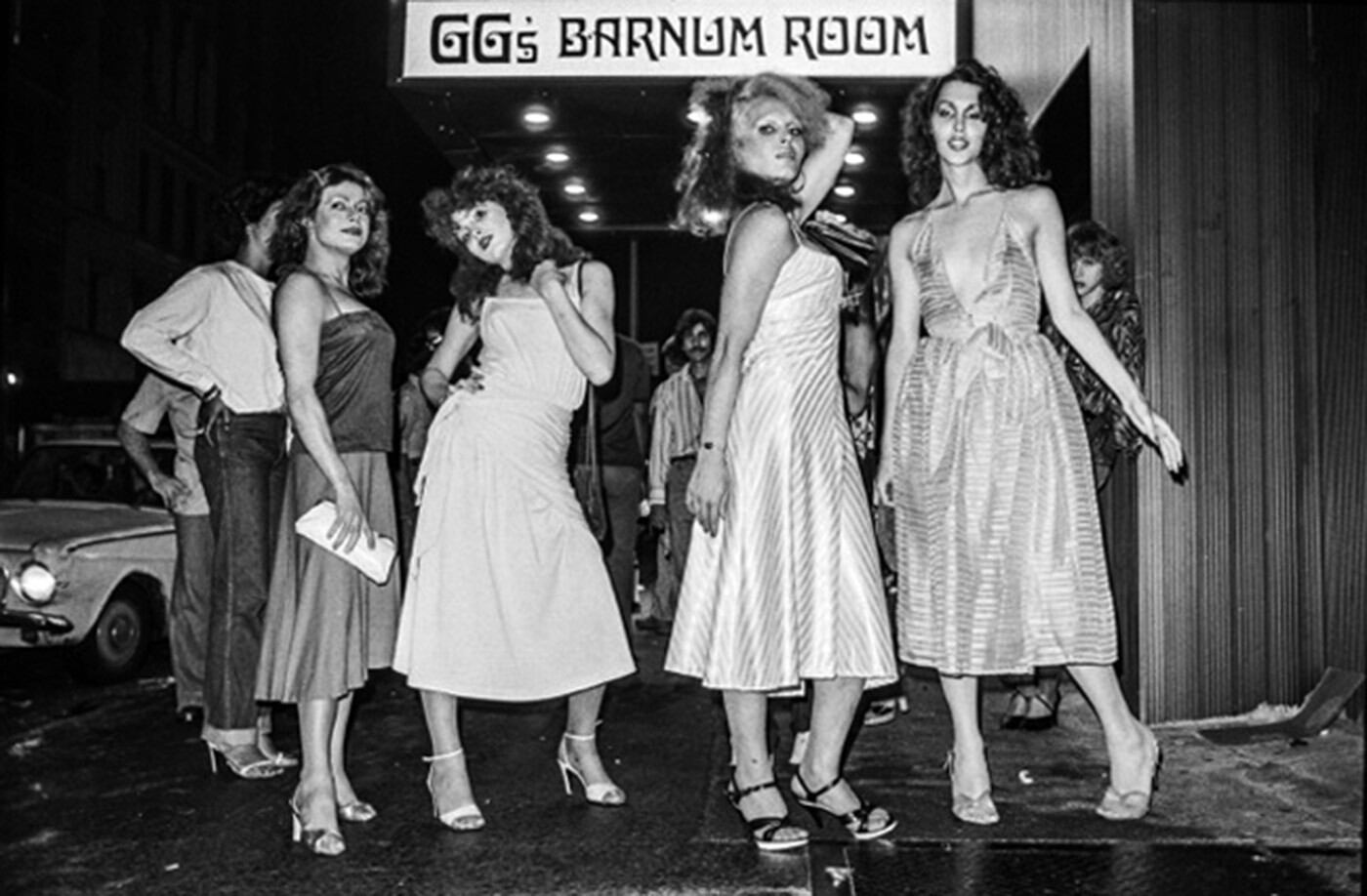

Times Square in the 1970s. Photo: James Hamilton. Source: The Rialto Report.

An eighteenth century pornographic cartoon features Marie Antoinette and Lafayette. License: public domain.

It is because we think via fantasy, rather than solely through rational processes of cognition, that we can do unexpected things with viruses. This, at least, was my contention in Unlimited Intimacy, an informal ethnographic study of the particular subculture that emerged in the United States toward the end of the twentieth century around barebacking—deliberate unprotected sex among gay men.3 The rational explanation for what appeared as a disconcertingly widespread abandonment of condoms, including in anal sex with strangers, was that middle-class gay men now had access to an armature of extremely effective pharmaceutical treatments for controlling HIV infection. Yet the availability of medications—highly active antiretroviral therapies (HAART) and pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP)—fails to adequately explain the efflorescence of a specific sexual subculture, along with its own brand of pornography, based on viral transmission. For that one needs an understanding of fantasy—and not only because pornography, including so-called documentary porn, inevitably involves fantasy.4

What I discovered while researching condomless sex at the turn of the millennium was that gay men had not simply forgotten about HIV. Instead, many had incorporated it into their sex lives quite intentionally. The development of fantasies of viral transmission—expressed in a vernacular of “breeding,” “seeding,” and “pozzing” as forms of initiation into “the bug brotherhood”—testified to an inventive (not to say disturbing) approach to the human immunodeficiency virus. Men who identified as “bugchasers” and “giftgivers” were having sex with a virus, as well as with each other; at the level of fantasy, they were using HIV to form kinship bonds.5 One might say that, through a collective process of fetishization, these men were transforming HIV from a phobic object into an object of desire—though even that characterization strikes me as oversimplifying what was going on. Given how stridently pathologizing the discourse about barebacking was twenty years ago—and how unprotected anal sex had barely been acknowledged as the basis for a distinct subculture—I wanted to analyze it more dispassionately. Endeavoring to describe certain kinds of sexual activity as specifically subcultural practices, I aimed in Unlimited Intimacy to anatomize the fantasies fueling those practices as well. Without the fantasies, none of it made sense; only by grasping the unconscious rationalities that organized the subculture could barebacking be distinguished from self-destructive hedonism.

My goal at that time was neither to defend nor to denounce bareback subculture, but instead to think alongside it; I tried to take its fantasies seriously rather than simply dismissing them. Because I refused the predictable route of critiquing condomless sex among gay men, some readers of Unlimited Intimacy believed I was celebrating the subculture as transgressive and queer. That is a misreading based on the methodological incomprehension borne of politicizing complex phenomena too quickly. We need to be able to think about difficult material without either praising or condemning it. And, especially when it comes to viruses, we need to make space for thinking that eschews the blame/praise binary, without supposing that our thinking thereby escapes the mediation of fantasy. The idea of “misinformation” tends to assume that people just need the right information—scientifically verified data—along with access to vaccines, medications, prophylactics such as masks or condoms, and the proper support. But that ignores all the ways in which fantasy mediates people’s thinking about virality. My claim is that “misinformation” is itself a misleading idea.

The subculture I documented in Unlimited Intimacy has since been transformed thanks to PrEP, a once-a-day pill (marketed in the US under the brand name Truvada) that prevents HIV infection by inhibiting the reverse transcription the virus needs to replicate. Barebacking is not what it once was. Condomless sex among men on PrEP can no longer be characterized as “unprotected” sex; the risks have changed substantially, though the fantasies have not evaporated.6 Bareback subculture may be worth considering in the era of Covid-19 because it offers an example—by no means definitive—of what it might mean to live with a virus, rather than only to die from it. The Covid-19 pandemic has furnished a parable about how people navigate, or fail to navigate, viral intimacy. How do we want to live with this coronavirus, with its variants and subvariants, which have entered our world with an alacrity that caught almost everyone off guard?

In May 1990, ACT-UP mounted a protest at NIH to raise public awareness of the lack of biomedical research in combating HIV-AIDS. License: public domain.

From HIV to SARS-CoV-2

Despite the prominence of Dr. Anthony Fauci during not only Covid but also the early years of AIDS, it has often felt as though US society learned nothing from the previous pandemic. For those involved in AIDS activism during the eighties and nineties who are still alive today, Fauci represents a striking point of continuity between then and now. In light of that continuity, it is disheartening to witness how many of the social reactions to SARS-CoV-2—vehement denial, hysterical othering—along with the government missteps and institutional bungling all appear consistent from one pandemic to the next. Even with monkeypox, it seems that the US has failed to grasp the lessons of recent pandemic history (“The response in the United States has been sluggish and timid, reminiscent of the early days of the Covid pandemic … raising troubling questions about the nation’s preparedness for pandemic threats”).7 Again and again, we are confronted with the inadequacies of our public health infrastructure—inadequacies that new, emerging, and long-established viruses all readily exploit. Queer sexual culture in 2022 faces not only renewed discrimination (“Don’t Say Gay”) but also the syndemic of HIV, Covid, and monkeypox, as viruses circulate and mutate. Since there is no shortage of parallels among these overlapping pandemics, targets for queer critique proliferate.

Yet, the fact that SARS-CoV-2 is airborne, and therefore exponentially more transmissible than HIV, limits the parallels that may be drawn between these viruses and their respective pandemics. The persistent underestimation of this coronavirus’s transmissibility contrasts sharply with the general overestimation of how easy it is to get HIV. Those differences tend to be obscured by fantasies about purity and contamination. If Covid is understood primarily through the lens of experiences with HIV/AIDS, then the specificity of both pandemics risks being erased. It is not only ignorance and denial that defend against the novel and unknown, but also established frames of reference: the knowingness with which some commentators viewed the Covid pandemic is part of the problem. Differences between mechanisms of viral transmission, and their implications for intimacy, remain indispensable here.

Although the pathological entity subsequently named “acquired immune deficiency syndrome” first attracted medical notice in 1981, its viral cause was not identified until 1983 and not definitively named as HIV until 1986. Easy to forget, forty years later, the social panic that once surrounded this new disease’s uncertain mechanisms of transmission. During that early period, fear about HIV/AIDS spread more rapidly than the virus itself. Entrenched homophobia stoked anxieties that one could “catch AIDS” from ordinary social interaction—by shaking hands or dining in restaurants, for example, or simply by being around gay people. Homosexuality itself was regarded as contaminating. Once transmission mechanisms were known, however, it became tremendously important to emphasize that HIV could not be spread through ordinary social interaction. Gay men then realized that the pandemic driver of asymptomatic transmission need not pose an insuperable problem after all. You just had to approach every potential sex partner as if they were HIV positive and avoid exchanging bodily fluids.8 Easier said than done, of course, especially if activities such as cum-swapping were integral to your sense of erotic intimacy.

Nevertheless, there emerged in gay sexual culture an ethos that insisted we were all living with HIV, regardless of anyone’s actual serostatus. Early in the pandemic, we redescribed “AIDS patients” as “people with AIDS” (PWAs); as it became evident that one could be HIV positive for a decade or more without developing symptoms, we reframed the person “dying from AIDS” as one “living with HIV”; in a concerted effort to destigmatize the disease, we avowed that we were all living with HIV, albeit unequally. Phrases such as “person with AIDS” foreground the person rather than the infection, condition, or disability, while also highlighting the conjunction with as a potential sign of togetherness. If you are with, you are no longer isolated or alone; with implies a degree of intimacy, for better or worse. It is the status of living-with, or being-with (mitsein), that we now are trying to conceive in the massively expanded context of the virosphere—the global totality of viruses, those identified and named, as well as the legions unknown.

Although there is still no vaccine or cure for HIV disease, people have learned to live with this virus in various ways. Bareback subculture remains among the least anticipated ways of living with HIV, because it embraces the virus by eroticizing its transmission. Hardly surprising, then, that survivors of the traumatic early years of AIDS—when there were no effective treatments, just stigma and terror and death—often become enraged at the very mention of organized barebacking. Gay elders such as Larry Kramer could see in bareback subculture only the reckless dissemination of illness and death. What one self-identified barebacker described as an experience of “unlimited intimacy” may be viewed conversely as manifesting unwanted intimacy. Recently I have come to think that SARS-CoV-2, owing to its greater infectivity, is the virus that better exemplifies unlimited—and unwanted—intimacy.

As with HIV/AIDS, the Covid-19 pandemic is driven in part by asymptomatic transmission. Unlike with HIV/AIDS, however, ordinary social intercourse, including indoor restaurant dining, offers ample opportunity for SARS-CoV-2 to spread. If the most salient feature of this coronavirus is that it is airborne, nevertheless it took the World Health Organization and the US Centers for Disease Control too long to register the fact. Not until late in April 2021 did the WHO publicly acknowledge that this virus spreads via aerosols (tiny respiratory particles that remain suspended in the air) as well as via respiratory droplets (which stay airborne only momentarily and generate fomites when they land on surfaces).9 In a compelling account of institutional reluctance to acknowledge the role of aerosols in viral spread, sociologist Zeynep Tufekci relates how the emergence of modern germ theory during the nineteenth century gradually displaced miasma theories of disease. It was not foul smells and bad air that caused illness, but pathogenic particles invisible to the naked eye: microbes replaced miasma. However, that advance in the scientific knowledge of disease subsequently made the significance of aerosol transmission harder to accept, insofar as it hearkens to outmoded theories about “bad air.” Tufekci elaborates:

If the importance of aerosol transmission had been accepted early, we would have been told from the beginning that it was much safer outdoors, where these small particles disperse more easily … We would have tried to make sure indoor spaces were well ventilated, with air filtered as necessary. Instead of blanket rules on gatherings, we would have targeted conditions that can produce superspreading events: people in poorly ventilated indoor spaces, especially if engaged over in time in activities that increase aerosol production, like shouting and singing. We would have started using masks more quickly, and we would have paid more attention to their fit, too. And we would have been less obsessed with cleaning surfaces.10

Those who believed that SARS-CoV-2 spreads primarily through direct physical contact underplayed its capacity to hang in the air that surrounds us, the air we inhale and exhale, constantly and involuntarily. For too long we apprehended this coronavirus through a phobic tropology of contaminating touch, as if, like Lady Macbeth, rigorous handwashing might save us. But a virus understood as fully airborne—present in aerosols as well as in droplets—redirects the focus from surfaces to orifices, displacing attention from touch to breath. Breathing, a process of perpetual exchange between inside and outside, marks an original openness to the world beyond our discrete bodily envelopes. An aerosolized virus renders ordinary respiration a site of new vulnerability by disclosing how unself-contained we truly are. Now, more than ever, we are “living with” whether we like it or not—indeed, whether we acknowledge it or not.

Human respiration is an automatic activity that nevertheless remains amenable to discipline (think yoga), to politics (think “I can’t breathe”), and to fantasy. One correlate of the psychoanalytic theory of embodiment is that autonomic systems such as respiration are no less subject to fantasy than are the organs and systems of sexual reproduction. We need only consider the “breath play” involved in certain BDSM rituals—or the phenomenon of heavy breathing in an anonymous telephone call—to see how readily the mundane activity of respiration may be eroticized. Over sixty years ago, Jacques Lacan alluded, without elaboration, to “respiratory erogeneity.”11 And long before Covid-19, Instigator, a gay porn magazine produced in West Hollywood for the kink community, regularly depicted men having sex in gasmasks. It is because breathing functions as a process of exchange between inside and outside—and thus marks a vital bodily threshold—that it lends itself to metaphor, overcoding, and fetishization. In human subjects, respiration is never an exclusively physiological process, despite what some biologists prefer to believe.

We become intimate through the air we share. With SARS-CoV-2, one need mingle no bodily fluids, only breath: the atmosphere is our medium of intimacy. In the biopolitics of respiration, what we are sharing is effectively our insides. I take the image of “shared insides” from the German philosopher Peter Sloterdijk, whose Spheres trilogy redefines intimacy at multiple scales, including the atmospheric. “Like every shared life,” he claims in a revision of Bismarck, “politics is the art of the atmospherically possible.”12 If facemasks are but the most visible sign of this politics of the air, then perhaps we need a “spherological” critique of the virosphere. Notwithstanding Sloterdijk’s own politics, such a critique would need to begin by acknowledging that, as the sharing of air is unequally distributed, so is the atmospheric intimacy frequently unwanted. Social privilege tends to determine the quality and quantity of air you’re compelled to share, how many others you must perforce inhale. I can’t breathe—a rallying cry of the Black Lives Matter movement after the killing of Eric Garner—refers not only to African American citizens asphyxiated by the police but also to the suffocating effects of anti-Black racism in the United States more generally. In this context, Ibram X. Kendi names racism as “the original American virus.”13

Not being able to breathe freely is both a metaphor and, too often, a material condition as well. “Breathing in unbreathable circumstances is what we do every day in the chokehold of racial gendered ableist capitalism,” writes Alexis Pauline Gumbs.14 Indeed, as various critics have argued, it is the political atmosphere as much as what is airborne in the virosphere that compromises human respiration.15 My point is that the identification of SARS-CoV-2 with a respiratory illness (severe acute respiratory syndrome) helps to distinguish it from HIV (which gives rises to an immunodeficiency syndrome when left untreated). Emphasizing the respiratory dimension differentiates Covid from AIDS, while at the same time connecting Covid with the epidemic of police violence that sparked protests worldwide following the murder of George Floyd on May 25, 2020. Although SARS-CoV-2, like all viruses, remains invisible to the naked eye, Floyd’s death achieved global visibility during the first year of Covid, becoming an iconic image of suffocation. His death was the one whose cause we all could see. I can’t breathe is the anguished cry that links Covid-19 with Black Lives Matter through the biopolitics of respiration.

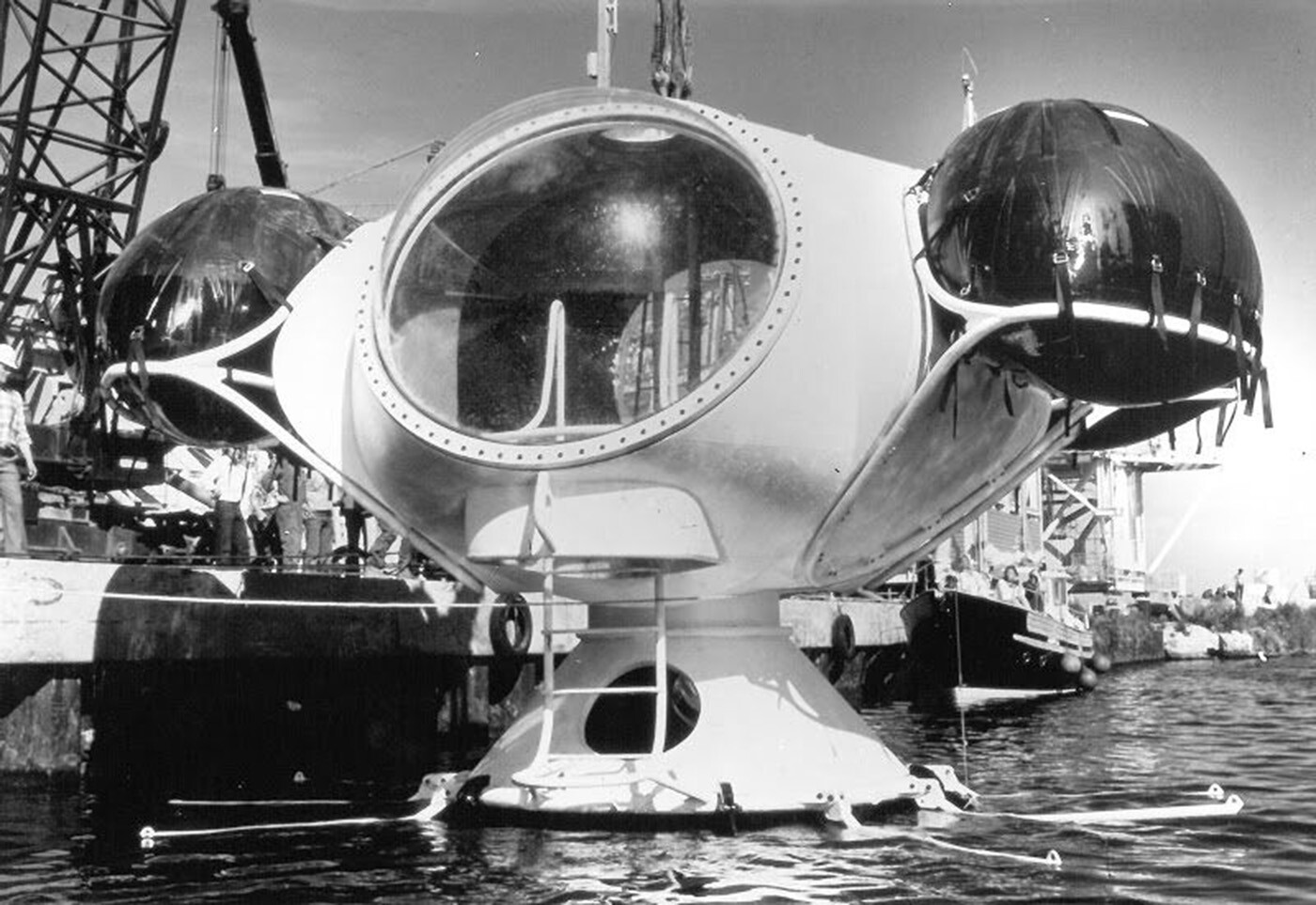

Galathée, an underwater habitat and laboratory by architect Jacques Rougerie.

Breathing Intimacies

Akin to the rhythms of breathing, respirational biopolitics pushes in opposite directions—negative and affirmative—at once. I advocate for considering the creative and erotic possibilities of this biopolitics, as well as its destructive side. If we take Michel Foucault’s preliminary definition of biopolitics as involving the power to make live or let die, then we may see the negative pole of respirational biopolitics in the unequal distribution of risk during the Covid-19 pandemic, which allowed the elderly, the poor, and the disenfranchised to succumb more readily to respiratory illness. Older people may be more physically vulnerable to disease, but that vulnerability has been exacerbated by social attitudes that permit their segregation into badly ventilated and poorly monitored nursing homes, which quickly turned into morgues during the pandemic’s first wave. Our culture’s pervasive devaluing of its elders makes of them a disposable population that may, in Foucault’s words, be “let die.”16 Respirational biopolitics hits home when the burden of risk in breathing is borne unequally—when we share the air but refuse to share its risks.

The negative pole of the biopolitics of respiration manifests also in those logics of social segregation that allow some people to breathe more easily by leaving others to bear the brunt of environmental pollution. The Covid-19 pandemic has made clear how humans are universally vulnerable to airborne viruses—though some are rendered, by deliberate social policies and by neglect, as vastly more vulnerable than others. For example, the elevated incidence of asthma among African American populations, resulting from more frequent exposure to air pollution, intensified their vulnerability to this new respiratory virus.17 If the biopolitics of respiration contributed to Eric Garner’s asthma in some unquantifiable way, then in his case biopower fatally intersected with a performance of sovereign power—the ancient right to take life—when a New York City police officer put him in a chokehold on July 17, 2014. Sovereign power (embodied in the monarch or ruler) involves the right to take life or let live, whereas biopower (diffused throughout social processes rather than embodied in individuals) involves the right to make live or let die. It was biopower that left Garner struggling to breathe with asthma, and then an illegitimate exercise of sovereign power by the police that asphyxiated him.

The Italian philosopher Franco “Bifo” Berardi reports feeling “asthmatic solidarity” when he watched the video recording of Garner’s last, gasping breaths.18 Berardi’s sense of solidarity stems not from national or racial identification, but from the elemental struggle to breathe shared by people with asthma. In this view of respiratory biopolitics, what is shared is less air or breath than the struggle for it—a struggle Berardi understands to be political as well as physiological. When George Floyd died after a Minneapolis police officer knelt on his neck for more than nine minutes, the sense of solidarity sparked around the world, in people of all nations and races, testified to a globally shared feeling of respiratory vulnerability, as well as to the abhorrence of racial injustice and police violence. At that moment in 2020, unimpeded respiration could no longer be taken for granted by anyone.

Since breathing is not a purely passive process, the power of respiration may be actively mobilized for intimacy, for community, for eros, and for aesthetics. Struggling to breathe may become a basis for political solidarity. The affirmative pole of respirational biopolitics can be seen, for example, in projects of “feminist breathing,” which are usually collective and draw on rich traditions of Black feminism.19 In such endeavors, women gather not only to talk, exchange information, and strategize, but also to breathe intentionally together. Collective respiration begets inspiration. For one queer Black feminist, it inspires the acknowledgement that breathing is “beyond species and sentience”:

Is the scale of breathing within one species? All animals participate in this exchange of release for continued life. But not without the plants. The plants, in their inverse process, release what we need, take what we give without being asked. And the planet, wrapped in ocean breathing, breathing into sky.20

Human respiration depends on an exchange of gases that involves—and thereby connects—all planetary life. In her lyrical meditation on breathing, Gumbs explores the fact that marine mammals process air similarly to land mammals as a way of challenging human exceptionalism. Her analysis pushes so far beyond identity politics as to evoke “trans-species communion.”21 Our mutual dependence on the earth’s atmosphere means that the biopolitics of respiration must be a multispecies affair.

It is perhaps no coincidence that Gumbs, the Black feminist author of reflections on mammalian respiration, is also a poet, since poetry entails hyperawareness of breath, its rhythms, and of a performer’s lung capacity. Poetry, in purposefully making art out of breath, contributes to the positive aesthetics of respiration, suggesting how to do things not only with words but also with air.22 There is power in sharing and in shaping breath together. Another poet, Jennifer Scappettone, locates the issue of poetic breath in the context of air pollution: “Seen not as an empty virtual space but as particulate, air makes for a democracy of harm that has had artists and authors strategizing for remedies for generations—remedies that are always necessarily incomplete.”23 In air contaminated by particulate matter, whether from industrial factories or forest fires, we now appreciate the additional threat of airborne viruses. Ironically, an in-person poetry reading, once a vital source of community, may serve in the age of Covid as a super-spreader event. If it has become harder to disentangle the negative from the affirmative poles of respiratory biopolitics, then this may be because the atmosphere we breathe intersects with what we are coming to understand as the virosphere. We inhabit—and are inhabited by—both spheres at once.

Healthy human beings carry approximately 174 species of virus in their lungs alone, most of whose functions are unknown.24 It is not only that millions of viral species remain unfathomed by science, but also that viruses equivocate standard biological definitions of life; we live with them, vastly outnumbered, while barely knowing them at all. Since viruses challenge fundamental human ways of knowing, including scientific epistemologies, it is extremely difficult to discuss them without using metaphors that may help us grasp them even as we thereby misconstrue them. A team of virologists from Brazil has observed how the science of virology tends to apprehend viruses from an anthropocentric point of view, which inevitably distorts perspective.25 When we consider the virosphere anthropocentrically, we naturally want to know, first and foremost, which viruses are likely to harm us. From the perspective of human life, viruses tend to be regarded as potential enemies—as “foreign invaders” against which we must defend ourselves by every means possible.

This view of viruses as foreign to—rather than part of—the human may be traced to assumptions about immunity as a biological property of individual bodies. Before it became a medical concept at the end of the nineteenth century, immunity was a longstanding legal and political concept that concerned an individual’s rights of self-defense against the community. Roberto Esposito, an Italian philosopher of biopolitics, argues that ancient political ideas about the foreigner and the enemy have been encoded into our biomedical concept of immunity, with profound consequences for understanding how biopower functions in modernity.26 Following Esposito and Foucault, cultural historian Ed Cohen develops the connection between political and medical notions of immunity by showing how the idea of immunity-as-defense became naturalized in modern science.27 If what humans take to be our biological immune systems operate by identifying and rejecting that which is deemed foreign, then the notion of immunity assumes an antagonistic stance toward the question of “living with” from the outset. Our understanding of the virosphere is distorted by the paranoid fantasy that viruses are always our enemy.

An antagonistic approach to the virosphere overlooks all the ways in which, as Eben Kirksey says, “viruses are us.”28 Already among and inside every human body, viruses remain inseparable from Homo sapiens. Yet even those viruses unknown to science need not automatically be considered as foreign; that which is unknown is not inevitably hostile or threatening. The Brazilian virologists who registered the anthropocentric bias of their ostensibly objective scientific discipline claim that “a huge effort and change in perspective is necessary to see more than the tip of the iceberg when it comes to virology.”29 We need to not only learn more about viruses but also fundamentally rethink the paradigms through which we approach them. For example, the anthropologist Heather Paxson has proposed the notion of microbiopolitics “to call attention to the fact that dissent over how to live with microorganisms reflects disagreement about how humans ought to live with one another.”30 The bios of biopolitics is replete with microbes, including viruses, just as our biosphere encompasses the virosphere. Perhaps, in the end, viruses may be useful for their capacity to confound the antagonistic us-versus-them mentality on which the concept of immunity is based. Viruses are us and not-us simultaneously.

The Covid pandemic has made plain that how we think about virality is shaped but not totally determined by scientific ways of knowing. I have suggested that viruses, in their troubling of boundaries between inside and outside the human body (as well as their equivocating the border between me and not-me), remain susceptible to the workings of unconscious fantasy. Although fantasy frequently functions as a defense against unwelcome realities, it also bears the potential for creative thinking about phenomena that remain invisible to the naked eye; not all fantasies are paranoid. One example of that creative thinking would be those subcultural fantasies that treat the human immunodeficiency virus less as an enemy to be feared than as a friend to be embraced. It is not only hardcore barebackers but also reputable researchers who aspire to invert the enemy-friend polarity when it comes to conceptualizing human-virus relationships. In her work on HIV, for example, the French anthropologist Charlotte Brives advances a model of “reciprocal domestication” to describe the ongoing symbiosis that may develop between virus and host.31 Picturing viruses “as companion species,” Brives joins scholars who are pushing beyond the imaginary us-versus-them mentality that otherwise constrains thinking about virality.

Unfortunately, however, the “companion species” approach to viruses risks simply inverting the enemy-friend polarity without effectively dislodging its terms—terms we’ve inherited from classical political philosophy that have been the source of so many problems in our attempts at living with others, human and nonhuman. The scientific conceptualization of immunity has made it extremely challenging to conceive of viruses outside this friend-or-foe paradigm. Even Kendi’s characterization of racism as “the original American virus” relies on the metaphor of virus as an obstacle to human flourishing and racial justice; he keeps virus in the “enemy zone.” If we cannot evade metaphorical conceptions of viruses, perhaps we can creatively elaborate them beyond the binary friend-or-foe framework that currently dominates, as it distorts, our thinking. Though hardly consolation, it may help to bear in mind that virtually the sum total of those highly complex social and viral worlds we inhabit is neither our friend nor our enemy.

See Simon Watney, Policing Desire: Pornography, AIDS and the Media (Methuen, 1987); and Leo Bersani, “Is the Rectum a Grave?” October, no. 43 (1987): 197–222.

See Jacqueline Rose, States of Fantasy (Clarendon Press, 1998); and Slavoj Zizek, The Plague of Fantasies (Verso, 1997).

Tim Dean, Unlimited Intimacy: Reflections on the Subculture of Barebacking (University of Chicago Press, 2009).

Treasure Island Media, the San Francisco–based porn company most closely associated with bareback subculture, originally represented its product as a documentary form.

See Tim Dean, “Breeding Culture: Barebacking, Bugchasing, Giftgiving,” Massachusetts Review 49, no. 1–2 (2008): 80–94.

See Tim Dean, “Mediated Intimacies: Raw Sex, Truvada, and the Biopolitics of Chemophrophylaxis,” Sexualities 18, no. 1–2 (2015): 224–246; and Raw: PrEP, Pedagogy, and the Politics of Barebacking, ed. Ricky Varghese (University of Regina Press, 2019).

Apoorva Mandavilli, “The US May Be Losing the Fight Against Monkeypox, Scientists Say,” New York Times, July 8, 2022 →.

See Douglas Crimp, “How to Have Promiscuity in an Epidemic,” October, no. 43 (1987): 237–71.

Zeynep Tufekci, “Why Did It Take So Long to Accept the Facts About Covid?” New York Times, May 7, 2021 →; and Trisha Greenhalgh et al., “Ten Scientific Reasons in Support of Airborne Transmission of SARS-CoV-2,” The Lancet, no. 397 (May 1, 2021): 1603–5.

Tufekci, “Why Did It Take So Long?”

Jacques Lacan, “The Subversion of the Subject and the Dialectic of Desire in the Freudian Unconscious,” Écrits: The First Complete Edition in English, trans. Bruce Fink (Norton, 2006), 692.

Peter Sloterdijk, Spheres, vol. 2: Globes, trans. Wieland Hoban (Semiotexte, 2014), 967.

Ibram X. Kendi, “We Still Don’t Know Who the Coronavirus’s Victims Were,” The Atlantic, May 2, 2021 →.

Alexis Pauline Gumbs, “Undrowned: Black Feminist Lessons from Marine Mammals: Why We Need to Learn to Listen, Breathe and Remember, across Species, across Extinctions and across Harm,” Soundings: A Journal of Politics and Culture, no. 78 (2021): 21.

See Sara DiCaglio, “Breathing in a Pandemic: Covid-19’s Atmospheric Erasures,” Configurations 29, no. 4 (2021): 375–87.

Michel Foucault, “Society Must Be Defended”: Lectures at the Collège de France, 1975–1976, ed. Mauro Bertani and Alessandro Fontana, trans. David Macey (Picador, 2003), 241.

See Antoine S. Johnson, “From HIV-AIDS to Covid-19: Black Vulnerability and Medical Uncertainty,” African American Intellectual History Society, June 15, 2020 →.

Franco “Bifo” Berardi, Breathing: Chaos and Poetry (Semiotexte, 2018), 15.

Jean-Thomas Tremblay, “Feminist Breathing,” Differences: A Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies 30, no. 3 (2019): 92–117; and Alexis Pauline Gumbs, Undrowned: Black Feminist Lessons from Marine Mammals (AK Press, 2020).

Gumbs, “Undrowned,” 20.

Gumbs, “Undrowned,” 24.

See Jean-Thomas Tremblay, Breathing Aesthetics (Duke University Press, 2022).

Jennifer Scappettone, “Precarity Shared: Breathing as Tactic in Air’s Uneven Commons,” in Poetics and Precarity, ed. Myung Mi Kim and Cristanne Miller (State University of New York Press, 2018), 47.

Dana Willner et al., “Metagenomic Analysis of Respiratory Tract DNA Viral Communities in Cystic Fibrosis and Non-Cystic Fibrosis Individuals,” PLoS ONE 4, no. 10 (2009) →.

Rodrigo A. L. Rodrigues et al., “An Anthropocentric View of the Virosphere-Host Relationship,” Frontiers in Microbiology, no. 8 (August 2017): 1673.

Roberto Esposito, Bios: Biopolitics and Philosophy, trans. Timothy Campbell (University of Minnesota Press, 2008); and Esposito, Immunitas: The Protection and Negation of Life, trans. Zakiya Hanafi (Polity Press, 2011).

Ed Cohen, A Body Worth Defending: Immunity, Biopolitics, and the Apotheosis of the Modern Body (Duke University Press, 2009).

Eben Kirksey, “Virology,” in Unknown Unknowns: An Introduction to Mysteries, ed. Emanuele Coccia (Triennale Milano XXIII International Exhibition Catalogue, 2022), 186.

Rodrigues et al., “An Anthropocentric View,” 1.

Heather Paxson, “Post-Pasteurian Cultures: The Microbiopolitics of Raw-Milk Cheese in the United States,” Cultural Anthropology 23, no. 1 (2008): 16.

Charlotte Brives, “From Fighting against to Becoming with: Viruses as Companion Species,” HAL: Open Science, June 1, 2017 →.

Subject

Thanks to Antoinette Burton, Lucinda Cole, Eben Kirksey, and Ramón Soto-Crespo for helpful feedback on this essay.