What is the afterlife for the undead? I am living it. I am referring to the “I” that was no singular “I” but a plural self that is and was an off-balance persistence—an assemblage of concurrent metabolisms unfolding in discordant synchrony. “I” am a holobiont with an alien alterity within: a virus. Whether a virus is living, dead, or undead is the wrong question because its animated copresence is world-making.1 A virus has entered into and shaped all my relations and possible life trajectories since its transmission.

Invisible to the human eye and some even to light waves, viruses do not figure easily into mental models of representation. They inhabit the micro- and nanospheres, yet their reach is planetary. The material worlds of viruses must instead be conjured through a secondary semiotic of affects, indices, and symptoms. To grasp the inhuman scales of viral agency, we elaborate analogies and science fictions to map their movements in our minds.2 In this way, our own bodies become science fictions dependent upon and resistant to the ordering genres and narrative devices of medical epistemologies.

It is therefore easy to understand how viruses, fathomable only by means of scaffolds of metaphors, are evacuated of their material relations and come to operate as the metaphor itself. Theorists and politicians alike often deploy the virus as a figure that stands in for agents with fuzzy boundaries who threaten to leak and contaminate: capitalism, communism, populism, immigrants, the underclass, terrorists, media popularity, and digital sabotage. Figuring threats as viral corresponds to a primitive, combative defense mechanism that further activates xenophobic tropes of war and conquest.3 And so we become ensnared in a battle of metaphors that are out of touch with the material relations of viral being and being-with viruses. Who among us has been in an extended relationship with a viral presence? Who has called a virus their kin?4

Viruses cannot be treated as a uniform block. They have their own characteristics from one strain to the next, just as their relationship with a holobiont body will have its unique humors. They circulate through wildly different media and bodies of transmission: alternately preferring blood, saliva, surfaces, atmospheres, sea water, microplastics, feces, sexual fluids—but rarely all of these. Each has its own tolerances for oxidation, desiccation, and solar radiation. Some viruses are structured by tensegrity into geodesic domes, whereas others are shaped like lemons. They require the development of an entirely different set of attentions to places of touch and encounter, where human sociality is in symbiosis with more-than-humans, and where contagion and communication are inseparable. I practiced perceiving the semiotic of the inhuman through my own lifelong intimacies with a particular genotype of a common blood-borne virus.

From 1981 to 2015 I lived chronically infected with the hepatitis C virus (HCV), which tells you something about my age that my face would not tell you. A friend joked that he wished he could be infected with my virus because, clearly, its threat on my life was doing something that protected me from aging. I thought maybe it had to do with the virus’s demand that I spend so much time sleeping, my face in suspended animation rather than lively expression. I liked his joke, especially since I was not expected to live long enough to show signs of age.

I am full of rage. The mass deaths of half a million people each year due to HCV is utterly normalized, and as with Covid-19, these are disproportionately the deaths of low-income people and people of color around the world. In a culture of toxic positivity that praises the silence of people living with illness as graceful discretion and a valiant refusal to be defined by disease, I was vocal about living with a virus and the obligation to dismantle structural inequalities that block access to health and well-being for the marginalized, who are already marked as less deserving of care and empathy. I could care less—I want collectivization of infrastructures for health and public ownership of medical resources. Ongoing global vaccine inequity and the barely mourned deaths of fifteen million people in two years of the Covid-19 pandemic say all we need to know about care.

Kinship is often extended as another name for care, implying that with mutual reliance comes reciprocity. But who among us has not been disappointed by our families, both chosen and assigned? Or perhaps we betrayed our own voluntary responsibilities to others, or committed an error of misrecognition when we offered a pact of kinship that was not returned? For example, the house cat caught a garter snake and was playing with its writhing, bleeding body in one of my earliest memories. I rescued the snake carefully from the cat and held its head in my hand, looking into its eyes to ask if it was okay. It snapped open and shut its diamond mouth full of blood, trying to bite me. I was confused by this response to being rescued from death, and promptly released it into the grass, protecting it from the cat’s hunt. A week later, the snake reappeared in the garden, larger and marbled with scabs from its wounds. I was delighted to see it alive and tried to say hello. The snake did not recognize me and slithered away from my hopes for reptile kin. Perhaps its suspicion was that care is another name for control.

I learned from the snake not to seek recognition from the virus, and I learned from my family not to seek care in kinship. The virus was an ever-present feeling of vibrance and fury coursing through every cell touched by my circulatory system. It pooled in my liver where its painful density solidified. Its language was not logos, and I had no desire to indulge in the prosopopoeia of ventriloquism through which I would imagine what it would have to say to me in words. Instead, I tried to think like a virus, and to find other registers where its expressions could be interpreted. The virus attuned me to the other sensorial languages of more-than-human worlds, guiding much of the work I have produced over the past decades. Our relationship evidenced how agents of the nonliving co-form our bodies and subjectivities. This porosity and vulnerability to alien cohabitation is unbearable to those who believe themselves to be a singular subject, contained. As philosopher Jean-Luc Nancy argues in Being Singular Plural, “Being cannot be anything but being-with-one-another, circulating in the with and as the with of this singularly plural coexistence.”5

To everyone’s surprise, including my own, I did not die from the virus. Here I am, still alive like a nasty little bug. The story of this survival is long. Our time is short. Time, as in: no linear fucking time.6 Long, as in: long haul. Story, as in: the virus, the crip, and the patriarch in the lands of Gilead. The story I will tell is about the connective tissue that grafts these figures to each other, and how capitalism grows into bodies through kinship networks and supply chains of care.

Viruses are my kin. And like any kin, they have both loved and betrayed me.

Photograph of three aluminum signs posted altogether repeating the same thing in different words at length: PRIVATE PROPERTY / Private Property Gilead Sciences, Inc. / Unauthorized vehicles will be towed, etc. The signs are framed by the generous, sunlight-filtering branches of a locust tree. Beyond, a multistory, cubed, corporate building with blue-tinted glass walls—Gilead headquarters.

The Lands of Gilead

Let me tell you right now the one important thing you’ll ever need to know: Own things. And let the things you own own other things. Then you’ll own yourself and other people too.

—Toni Morrison, Song of Solomon

I drive south of San Francisco past the airport, hugging the bay through the ticky-tacky hillside box houses of Daly City, and approach the suburban cluster of small cities better known by the mythic name of Silicon Valley. Within them is Foster City, an artificial lagoon of dredged bay sand that was built in the 1960s. The extruded landfill reinforced by concrete hovers just above the tidal marshlands that fed the Ramaytush-Ohlone people with oysters before settler colonization in the nineteenth century. Foster City is expected to be swallowed within the next fifty years—either by rising sea levels due to global warming, or by ground liquefaction when the Hayward Fault delivers its seismic revolt. I turn in to park at Gilead Sciences at 333 Lakeside Drive, the headquarters for one of the leading pharmaceutical companies in the world. With dozens of international corporate sites, Gilead holds a heavily patented cache on the market of prescription drugs to treat viruses including HIV/AIDS, hepatitis B, hepatitis C, influenza, and SARS-CoV-2 (Covid-19). Their luxuriantly priced, star-studded product portfolio includes Viread®, Truvada®, Genvoya®, Harvoni®, Tamiflu®, and Remdesivir®.

The future ruin of urban planning at the headquarters holds correspondence with its biblical namesake: the fabled lands of Gilead that no longer exist. They were believed to have been located east of the Jordan River in present-day Jordan. The landscaping here is neither showy nor unclipped. Concrete walkways are lined by fleshy, purple stalks of Agapanthus lilies, boxwood hedges, and fountain grasses that sustain their good looks when offered minimal care. There are no weeds, nor plants for herbal remedies. There is no smell.

“Is there no balm in Gilead; is there no physician there?” —Jeremiah 8:227

Many vegetal contenders vie to be the desert scrub that grew in ancient Gilead and whose resin forms a healing balm—but no species can be confirmed. The precious balm is referenced in the Old Testament as a marketable product (Genesis), as a gift (1 Kings), and as a metaphor for the soothing aspect of a wrathful god (Jeremiah). The ideological and colonial mechanism of Christianity excises structural inequalities of their geographic and sociopolitical specificity, and frames them as the pain of common human sin that can be cured by the healing powers of one physician: God. Faith is the balm of Gilead—an expression of a universal cure for a universal wound.

A venture capitalist educated at Harvard and Johns Hopkins founded the pharmaceutical company Gilead Sciences in 1987, two years after Margaret Atwood published The Handmaid’s Tale. Atwood’s novel and its television adaptation take place in the fictional Republic of Gilead, governed by a totalitarian Christian theocracy and caste-based patriarchy. The Republic is mapped onto the United States and filmed to mirror the Harvard campus and its beyond.

“Gilead is a city of evildoers and defiled with blood.” —Hosea 6:8

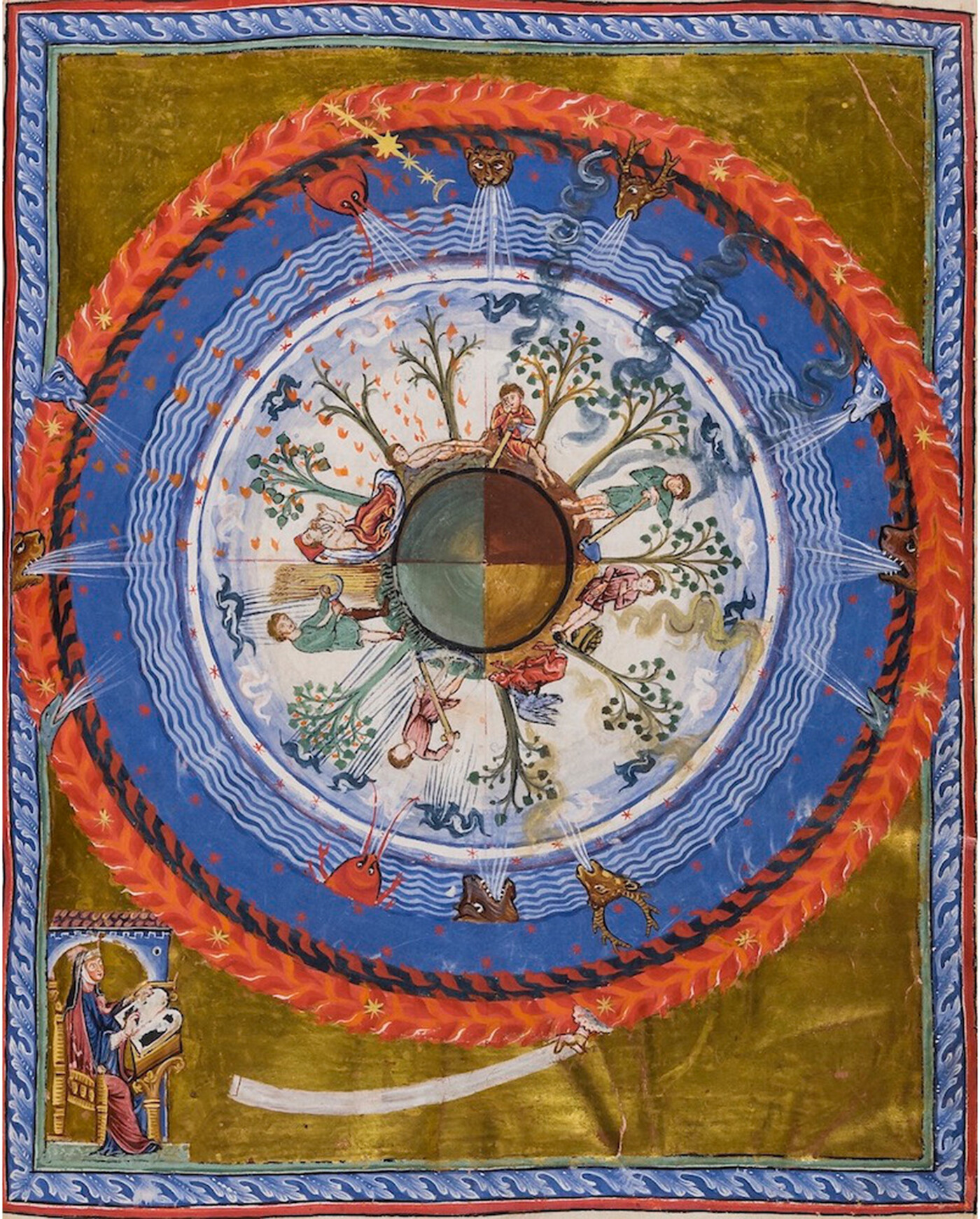

Hildegarde von Bingen, Liber Divinorum Operum (The Book of Divine Works), 13th century. Illuminated manuscript. Courtesy of the Ministry for Cultural Heritage and Activities—Lucca State Library. Hand-painted, colorful page from an illustrated manuscript: an erudite, robed white nun in the bottom corner opens a book, from which a divine hand gestures to a cosmological wheel that towers above her. A ring of fire and stars is given breath by the heads of many animals (snakes, lobsters, bears, deer with antlers, sea creatures) that spin around a globe divided into four, colored quarters. The globe is encircled by trees in seasonal change and the activities of a white peasant, alternately tilling the soil, sowing seeds, harvesting, and resting.

It is unclear whether the founder of Gilead Sciences had read Atwood’s dystopian novel before he named his company, or if he had even read the Bible, where the rocky landscapes of Gilead are a backdrop for ethnic genocides and endless sectarian wars over properties bequeathed by divine right. Instead, the founder was ostensibly inspired by the 1965 play Balm in Gilead, written by the acclaimed white, gay playwright Lanford Wilson. The play is set in an urban coffee shop, where a romantic tragedy plays out among a majority white cast of heroin addicts, hustlers, drug dealers, and a number of “girls who are Lesbians; some have boys’ nicknames; they might be prostitutes as well.”8 Poverty is excised of its origin in structural inequalities and hovers like a foul, atmospheric fog that propels the characters across their dialogue and interactions. It is fitting that the marginalized clientele of the fictional coffee shop is largely the same as that of Gilead Sciences. In other words, the characters in the eponymous play match the primary demographics of those affected by HIV and blood-borne viral hepatitis (except that the disease burden of these is further indexed by racial and ethnic disparities). People who are marginalized and lower income are disproportionately exposed to the risks of contracting life-threatening viruses, while chronic illness maintains poverty by disabling them from work and access to healthcare. Amidst the rapid, overlapping dialogues, a sex worker named Tig says, “You know in Egypt they had salves and things that could cure anything,” but no one in the play can seem to find a cure for poverty, nor even to arrive at a proper political diagnosis for their universal wound.9

Sex workers, queers, junkies, jailbirds, veterans, and pushers—they are also my kin. Both by blood and by viral association. They populated San Francisco’s streets and coffee shops in the early 1980s, selling pints of their blood to hospitals to get by amidst Ronald Reagan’s religious austerity politics that were hyperbolized in Atwood’s novel. In a San Francisco hospital, a quantity of the hepatitis C virus suspended in serum was transfused into me during surgery at four months old. The virus exposed me to categorical stigmatization and microaggressions as I carried its associations with drug addiction, nonmonogamous sex, prisoners, and poverty. Because the overwhelming majority of people in the US become infected with hepatitis C by sharing needles for intravenous drugs, most people who learned of my virus assumed that I was a user as well and modified their behavior towards me accordingly. I would watch their thoughts oscillate in the space of their withdrawal, a crust of revulsion precipitating along the edge of our encounter—so crisp I could eat it to feed my inhuman appetite. My refusal to disavow these associations when someone projected their judgment onto me gave me valuable information about whom I could trust. Even without the particular social contagions attached to hepatitis C, simply to enunciate and acknowledge the presence of a well-contained yet unknowable alien virus within me could provoke anxiety and avoidance in others.

Gilead, however, did not recoil; it stepped forward to make me feel seen, anonymously funding general awareness advertising campaigns to acknowledge my suffering, and inviting me into its care. Crafting a public image of benevolent innovation, Gilead increased its power within the political economy when it acquired the patent to the world’s first direct-acting antiviral medication that could permanently eradicate an infection with HCV. Gilead wanted an intimate relationship with me. It wanted me in aggregate: a human carrying a viral load, and a viral load that is a pandemic of tens of millions of people, singularly grievable and unquantifiably valuable, and each bringing with them a brood of insurance funds amounting to billions of dollars.

Public policies on drug development favor patent ownership and are designed to engineer a mass flow of wealth from the public to private corporations, while pricing drugs at rates that leave most who could benefit from treatments without access to them. To own patents is a form of biopolitical extraction that works like this: the majority of top pharma companies are headquartered in the US, with a few based in Europe, China, and Japan. Nine out of ten of the biggest international pharmaceutical companies spend more money on sales and marketing than they do on the research and development (R&D) of new treatments.10 One third of pharmaceutical R&D in the US is subsidized by taxpayers, who then pay an additional 40 percent markup on average for those drugs.11 No policies exist to ensure that the public receives a return on its own financial investments in research, or that access to the drugs are made equitable and affordable. Thus, we pay for drugs twice: once in the risky phase of development, and again to save our lives. Companies can set any price for patented drugs because there are no national or global legal limits, mandates for transparency, or protocols to determine their value. One key, obligated client is the US government itself, with a pool of federal insurers—Medicaid, Medicare, and the Veterans Health Administration—who are legally barred from negotiating prescription drug prices. Because the benchmark prices are most often set in the US, the absence of drug pricing policy there impacts health care costs worldwide, relegating global access to medicine to the domains of corporate philanthropy.12 Meanwhile, the top twenty-five pharmaceutical companies are among the most lucrative on earth, enjoying a net profit margin of 15–20 percent, versus most Fortune 500 companies, which average 4–9 percent.13

In between all these numbers is my body. Living with a virus for a lifetime and surviving two of its death threats led me into these relations of toxic kinship with biomedical capital.14 I circulated in an economy of sick bodies, where viral stigma and oppression are subsumed into the business and marketing models of pharmaceutical companies. Gilead does not withdraw from the social contagions of its clientele. To the contrary, it platforms them as virtue signaling for their philanthropic arm, which exists only to mitigate the inflated cost of their drugs. Stories of their support for trans Latinx mutual aid collectives are detailed in its news releases, where ongoing updates on its patient commitment programs can be followed. These are the charitable branches of the company that offer their medications to patients who apply with a personal appeal for help, either because they cannot obtain health coverage, or because they were denied treatment by their insurance due to Gilead’s established practice of setting benchmark prices for its medications at such a steep expense that many insurers refuse or restrict coverage for their patented drugs. Pharmaceutical companies work from and intensify the very conditions of wealth concentration and resource scarcity that structure health and access to medicine into a racialized global caste system.

Through tinted glass windows, I view a multimedia exhibition of Gilead’s “Social Justice Experience” installed in a carpeted lobby that “examines how systemic racism continues to affect Black Americans negatively—from police brutality and incarceration to HIV.”15 A wall-sized, monotone photograph of a Black woman in profile is on view. A long, single tear shines on her buoyant, youthful cheeks, and her African head wrap serves as the backdrop for a box displaying a brief definition of the word “intersectionality,” attributed to Kimberlé Crenshaw. The exhibition commemorates the company’s donation of $10 million divided over a fixed, three-year period to selected racial justice organizations, or a gift of .16 percent of its $6.225 billion annual net income in 2021. The lawyer and activist Dean Spade argues that carceral solutions and hypocrisy are the foundation of philanthropic care: “Elite solutions to poverty are always about managing poor people and never about redistributing wealth.”16

We are told that this structure is a necessity to produce life-saving medical treatments—will we continue to comply? The source of all this wealth is ours, and with a redirected flow, it could be ours again, for and with each other. If kinship is another name for care and care is another name for control and control is another name for capitalism, then Gilead is also my kin, and I have come here to plan to collectivize my (our) inheritance. The vacancy of the campus indicates that there is room for many.

Verbose signs on Gilead’s campus detail trespassing and private property violations, ground behavior protocols towards dogs and ducks, as well as anticipated exposures to formaldehydes and off-gassing construction materials if any of the ten or so glass and metal–clad corporate buildings are breached. Without an RFID tag, none of them can be. My hands fall away slack from their steel doors. I peer through the windows. I wait. I imagine a garden of herbal apothecaries subsuming the Agapanthus lilies to become a labyrinth of wild grasses where we can cruise, harvest, and nap. An empty parking lot can become a greenhouse where the plant-derived GMO growth serum will be cultivated to support in vitro experiments for health innovations designed and directed by those impacted. A long, glass hall adjacent to the lot is perfectly suited to become the supervised injection and needle exchange site, with a coffee shop next door. I get lost on a pathway encircling the artificial lake, where I encounter the only visible humans at the headquarters. Two South Asian men in office attire are lunching under the shelter of a newly ubiquitous ad hoc architecture to facilitate sociality while minimizing the airborne risks of SARS-CoV-2: the all-season bubble tent. I ask them how to get back to my car.

The Virus and the Crip

I’ll make it up to you, darling, in dog biscuits / in the afterlife / in makeshift dark / we can burst apart / any body / & no body / stays intact for long anyway

—Heather Phillipson, Whip-Hot & Grippy

In the year 1999, a subsection of environmentalists evolved into Y2K preppers, forecasting infrastructural meltdown when the Gregorian calendar was set to cross an arbitrary threshold into a second millennium of linear timekeeping. Those who held these views sometimes blended with zero-population-growth ecologists. Their version of the Gaia systems theory popularized an idea that the planet-as-self-regulating-organism was currently rectifying its problems of resource overconsumption by sloughing off overpopulated humans with plagues of HIV and global warming in the guise of floods, fires, and famine.17 The United Nations Population Fund contributed to the demography and datafication of this otherwise biblical-sounding apocalypse. Accusing conservation environmentalists of messianic delusions by mischaracterizing Gaia as fragile, scientist and cofounder of the Gaia theory James Lovelock wrote, “I see through Gaia a very different reflection. We are bound to be eaten, for it is Gaia’s custom to eat her children.”18

Was I a child to be eaten? I assumed so. The turn of the millennium was the year in high school when I was first diagnosed with having an incurable virus, and I accepted my fate as a casualty of Gaia’s self-regulating system. I had run away from a volatile and violent home to the other side of the North American continent by obtaining a scholarship to an elite boarding school. It was a formational move that was to become a pattern by which I substituted the kinship structures of a family with the infrastructures of an institution. Weekly all-school meetings were held in a chapel named after Thomas Cochran, a generous trustee and partner in J. P. Morgan and Company. In addition to my high school, Cochran’s altruism included funding research into what historian Emily Klancher Merchant called “birth control as a technological solution to poverty and a cost-saving measure for philanthropists that would allow them to devote more of their largesse to causes benefiting the wealthy than to causes benefiting the poor.” Or, in other words, a post-racial democratic version of eugenics.19

Sitting in the post-religious pews of the Cochran Chapel in 1999, I listened to an invited speaker address the school about the world’s “overpopulation burden.” She spoke to us with urgency about the links between environmental resource scarcity and the importance of philanthropy to bring birth control to women in the Global South, especially in Africa, which was depicted in her diagram as a continent-turned-thermometer where the burgeoning population would soon reach the red-hot top.20 The speaker gently tossed a slithered sash of straight blonde hair over the shoulder of her blazer to gesture at an illustrated slide of pestilent microbes and viruses. She said they were primed to infect a growing reservoir of the human population, and then flipped the switch to refer to humans as the virus overwhelming the planet. Yet it was clear by her geographic emphasis upon the birth rates of countries with Black and brown people that the figure of humans as a virus was racialized and born from the possessive fears of people living in high-GDP countries where they themselves were the most intensive users of resources. The realization came to me that I, as a white teenager infected and disabled by a virus, was not the intended target of this viral figuration, and that it is not Gaia with a cannibal’s appetite that animates pandemics and climate catastrophe, but rather it is wealthy white anxieties that produce necropolitical infrastructures of resource scarcity and organized abandonment.21

Though I was privileged with whiteness, I was a young person of low income with a then-incurable virus who could be denied healthcare based on preexisting conditions. Like the artist David Wojnarowicz, “When I was told that I’d contracted this virus it didn’t take me long to realize that I’d contracted a diseased society as well.”22 I was living in a system where the burden of cost and care for disability and chronic illness falls upon the individual and the voluntary altruism of their kinship network, rather than being shared as a matter of policy through collective infrastructures. My strategy was to make queer kin with the virus in a loving yet problematic collaboration towards survival as sympoesis.23 Why wage an incurable, internal war with an alien alterity? The love for my holobiont self was a practice of resistance to the external, daily corrosions I sustained, such as fear and revulsion due to my infectious virus; resentments and characterizations of being difficult; the denial of jobs when I requested accommodations for a disability; dismissal of symptoms as psychosomatic; dismissal of my interpretations of the disease since I was not a medical professional; accusations of laziness; social suspicions that I did not consume substances due to lack of curiosity or out of moral superiority; forbearance of personal and professional investment since I was destined for an early death anyway … I was not only a vessel to the virus; we had to negotiate together the autopoetic metabolism that suited our mutual longevity.

The virus manifested its love concurrent with threats of suffering and death. I did not take these threats personally. Being in coerced kinship with the virus showed me other ways for the body to meet the world. In practice, the demands of the virus were less unreasonable and violent than living with a disability according to the demands of normative neoliberal capitalism in the US. I cared for our holobiont, which required extraordinary work, time, and money to accommodate, but I could not always control the outcome. Every day was accompanied by pain and fatigue, but sometimes, despite having consumed a fortune of herbal remedies and taking all the best measures, I regressed into damaging autoimmune flares and energy deficits, for which the virus—not I—took the blame. There were feelings of both gratitude and grievance: the joyful abandonment of heteronormativity, living in the dilated space-time dimensions of queer failure;24 alongside isolating decisions like ending unexpected pregnancies because I was not expected to live long enough to parent, and to prevent viral transmission to another generation. The virus demanded a diligent resistance to linear time and to accelerationist capital time, reorganizing my capacity to labor around its energetic desires. It introduced me to being-with others living in deep, queer time, and like the unstable category of queerness that refuses to be known, the virus maintained its mysteries, opacities, and fundamental alterity. The love in being-with the virus taught me the with of recognizing the subtle signs and signals of people living with disabilities and chronic conditions of all kinds, from mental health to trauma to autoimmune disorders to mobility and aging, and how to think about care not as control or forming expectations about how a condition should unfold, or what I think someone else should need—but instead as a practice and process of responsiveness that is an ongoing, agonistic sympoesis.

I will never know what being in my youthful body would have felt like without the virus. The encounter that led to our inseparability arranged the fundamental frameworks for how and where life could unfold within the supply chains of neoliberal medicine. Even now in this afterlife of the undead, having eliminated the active virus from my bloodstream a few years ago with pharmaceutical intervention, I am still living in crip time with its retroviral hauntings.25 Hepatitis C is a retrovirus, which means that the virus can synthesize and integrate its RNA into the DNA genome of the host. Humans are already viral, with up to 50 percent of our holobiont genomes consisting of retroviral DNA. Although the complete course of the direct-acting antivirals I took are extremely effective at interrupting HCV replication such that the virus can no longer be detected in the blood and cannot be transmitted to another person, current research is uncovering in some people what are called “cryptoinfections” and “occult disease.”26 My prior tendency towards lethal tumor growth—generated by the inflammatory and autoimmune effects of HCV—is now reduced. However, its retroviral integration into my genome means that other microbes, immune functions, inflammations, and cell exchanges can turn on genomic switches to resuscitate viral activities, like a genetic hologram of the virus.27 This fresh research into retroviral hauntings points to hypotheses about how so many people—predominantly those with two X chromosomes—can become disabled by chronic fatigue and multiple sclerosis long after clearing an infection with the Epstein-Barr retrovirus.28

The fear of being changed by encounters with the unknown compels xenophobia. But we are irrefutably porous to the ontological with of Nancy’s being-with, and much of this with is relations we do not choose. Models for intergenerational practices of kinship and mutual aid are powerfully forged within systematic racism by those under the pressures of racial capitalism and colonization. Though, as I have argued elsewhere, mutual aid and chosen kinships attend to care work and world-building towards desired horizons, they cannot sufficiently address all aspects of global biomedicine.29 Inhuman intimacies and kinships with companion species may take place under coercion and contamination, but the terms of our relations to more-than-human kin is dependent upon our chosen practices of negotiation and resistance to the animacies of capital within our kinship networks.

Quartz jasper, “Orbit” Idaho, USA. From Roger Caillois Mineral Collection. Photo by Paul A. Harris. A museum display of a stone sliced in half and polished. The outer ring is smooth ochre with bits of rough white, which gives to an inner core of bright, orange-yellow with thin red rings that sharply define a steadily gazing iris.

The Patriarch

They say to wood, “You are my father,” and to stone, “You gave me birth.”

—Jeremiah 2:27

Being-with the virus put me into proximity with the animacies and personifications of capitalism within my own family relations. A consequence of the bourgeois practice of compulsory coupling is that many white people have been de-skilled in the survivance practices of forming and maintaining kinship networks outside of their own families, as well as eroding them from within. Gilead Sciences may be a larger personification of capital as described by Marx, possessed by an undead animism, but technocracy is upheld by the collective decisions of individuals. One of these agents was my maternal grandfather, Frank. His mother was disabled, and his father died when he was five, so Frank sold eggs on the streets of Detroit when he was a child to survive during the Great Depression. He first studied opera at Oberlin on a scholarship until he was drafted into the navy during the second world war, which made him eligible afterwards for a military scholarship. Opera was demoted to a hobby when he switched to studying economics at Yale, where he washed dishes and performed janitorial duties as they required of scholarship students then, and married an educated woman with inherited wealth. Frank went on to work at the World Bank, where his primary roles were calculating the projected costs of large-scale infrastructural projects and teaching capitalist investment strategies to the leaders of emerging economies in the Arab world. Fluent in Arabic, he worked primarily in Egypt, Iraq, Lebanon, and Jordan.

As can be expected for a postwar white man working for US economic interests, he did well enough for himself financially and was an avid player of the stock market with a particular penchant for technology patents. Despite his internationally sought-after expertise in building capitalist empires and his immersion in the worlds of the rich and politically powerful, Frank did not learn that it takes hundreds of years for wealth to firmly establish itself within a family.30 He failed to realize that not everyone is positioned to go from selling eggs on the street to being a millionaire. As one of his two grandchildren, I was never a recipient of his capital. He praised me for the industriousness of my academic and career achievements, offered me a few thousand dollars towards the “good investment” of graduate school tuition, yet he refused appeals for financial assistance with the life-saving yet impoverishing medical costs of a chronic illness.

My family met for a rare vacation in the winter of 2013, the year that saw the first approved direct-acting antiviral medication released on the market by Gilead, which could fully cure HCV in 95 percent of my viral genotype. Over dinner one night, I told my grandparents about the new drugs and my struggle to access treatment. The list price was set at a then unprecedented $84,000 for an eight-week minimum course of the life-saving drugs, despite most of the R&D having already been paid for by taxpayers and the manufacture of the drug costing just $100.31 Although the laws of the Affordable Care Act had just come into effect, meaning that this was the first time in my life that I could no longer be denied treatment based on preexisting conditions, insurers were denying the drugs to all patients except those who met narrow criteria on the brink of death. The drugs were too expensive and the virus too prevalent for all seventy-one million people to be treated. The artificially inflated cost is the primary barrier to eradicating the immense public health threat of the infectious virus that the WHO says should be possible by 2030. My doctors in the US told me that I could pay out of pocket, ask my family for help, start a GoFundMe, or try to appeal to the philanthropic branch of Gilead to gift me the medication, but my success was unlikely.

My grandparents were the only family I had who would be in any position to help financially with medical expenses. The anticipatory myth that care can be found in kinship under the pressures of capitalism held me under its spell as I sought every means to survive. I explained to them how it was a deliberate strategy of the pharmaceutical industry to cash in quickly on the mass sale of patented drugs to global federal insurers before other drug developments might introduce competition and lower the prices slightly. At this unwarranted and exorbitant price, Medicaid spent over $1.3 billion in 2014 to treat fewer than 2.4 percent of infections in the US.32 International policies to create legal limits or protocols for drug pricing and patents could change this system, but there is little political will to do so. My mother demanded that I postpone the discussion because it was ruining her dinner and left the restaurant to cry until I had finished with the details. My grandparents agreed it was a terrible situation, but they declined to offer support.

After two years of bureaucratic maneuverings, I was ultimately able to obtain the medication in 2015. I took out $15,000 in debt and migrated to Germany to enroll in public healthcare with the help of friends, colleagues, and the infrastructures of academic institutions. Gilead’s balm, Harvoni®, eliminated the active virus from my bloodstream within eight weeks.

“I” burst apart, the “I” that was a plurality with a viral load. The astonishment of daily life without persistent pain, fatigue, and hypervigilance to the risk of infecting other people and the risk of early death is indeed a beautiful afterlife. Mourning, however, is also part of this landscape. Without the vibrant presence of viral particles in my blood, without its constant exigencies of care, “I” feel a bit more singular, and search for other relations with which “one consents not to be a single being and attempts to be many beings at the same time.”33 Like a beloved, a trauma, a romance, a toxic relation, or a deep wound, the virus will always compose my plural self, even if active viral particles no longer vibrate their presence within my blood.

When I called my mother to share the news that I was definitively cured of my life-long illness and now had a good chance to outlive her, she immediately changed the topic of conversation to focus on her mildly improved cholesterol levels. Frank congratulated me when I told my grandparents about the result and said that my saga had also served as an investment tip that prompted his purchase of stock in Gilead. He added that so far, he had lost on his investment, and laughed with an open mouth.

Kinship is anarchy. Enigmatic and unruly, the social formations that go by this name evade the specifics of structure and definition. In its ideal form, kinship refracts into aspirational horizons: chosen families, loyalties, loves, queer futurities, ancestral conjurings, intuitive magnetisms. Without the burden of form and boundaries, the delivery of expectations cannot be demanded of kinship. And without expectations, there is no disappointment. Right?

Such are the longings for queer horizons and feral kinships that re-world our relations to humans and more-than-humans within the violent ordering of dominant ideologies. Anarchic desires light a path away from most forms of kinship, which are assumed through a default coercion—whether forged through state-recognized family structures, transactional bondage, or through measures taken to survive within limited options. Toxic kinships haunt us through inheritances both material and immaterial.34 Cutting ties with toxic kin is not always possible even if desired, the consequences weighed against the tolerability of ongoing abuse. Severance from kin could result in exile or death, and total self-reliance is a delusion.

Survivance is dependent upon negotiating and being-with toxic relations as much as chosen and desired ones. Furthermore, discerning the toxicities from the nourishments within the very same relationship is a familiar task of anguish. This is the practice of being-with the kinships we do not choose—human and more-than-human. This is the practice of living inside of contradiction and contamination.

A few years ago, my grandparents moved into assisted living and asked me what of their furnishings I might like to inherit. I requested the shelf of my grandmother’s books on death and damnation, but she was not ready to part with those, and suggested instead a grid of black-framed landscape etchings, which I accepted. I unboxed them when they arrived in the mail, checking the images against my memory, and called to ask about their provenance. My grandmother said they were a personal gift to Frank by the King of Jordan when he was working there, but that there was unfortunately no certificate or personal note to officiate the story, making their value nothing more than personal. She said they were reproductions of colonial-era depictions of the ancient lands of Gilead, which are thought to be in present-day Jordan. A biblical scholar, she added that the name Gilead is explained in Genesis 31:46 as derived from the Hebrew gal, “a heap of rocks,” and `edh, “witness.”

And so, Gilead is indeed an inheritance from my kin, the witness of rock, whose stony gaze I meet and recognize with a viral, inhuman alterity.

My thinking around the boundaries and animacies of the living and nonliving throughout this essay is further informed by: Mel Y. Chen, Animacies: Biopolitics, Racial Mattering, and Queer Affect (Duke University Press, 2012); John Dupré and Stephan Guttinger, “Viruses as Living Processes,” Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part C: Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences, no. 59 (2016): 109–16; What Is Life?, ed. Stefan Helmreich et al. (Spector Books, 2021); Lynn Margulis and Dorion Sagan, Acquiring Genomes: A Theory of the Origins of Species (Basic Books, 2002); Sianne Ngai, Ugly Feelings (Harvard University Press, 2004); Sylvia Wynter, “No Humans Involved: An Open Letter to My Colleagues,” in Forum NHI: Knowledge for the 21st Century, vol. 1 (Institute NHI Stanford, 1994), 42–73; Kathryn Yusoff, “Geologic Subjects: Nonhuman Origins, Geomorphic Aesthetics and the Art of Becoming Inhuman,” Cultural Geographies 22, no. 3 (2015): 383–407.

From 2006 to 2010, my early artworks attempted to follow and make sensible the spatial choreographies of viruses, contagion, medicine, and care. Life Cycle of a Common Weed, Viral Confections, Traces, Transfers. They were eggs to contain my rage. Leaky containers, obviously. They leaked and they haunted, made messes and embarrassments. Caitlin Berrigan, “The Life Cycle of a Common Weed: Viral Imaginings in Plant-Human Encounters,” WSQ: Women’s Studies Quarterly 40, no. 1–2 (2012): 97–116.

See Priscilla Wald, Contagious: Cultures, Carriers, and the Outbreak Narrative (Duke University Press, 2008); Neel Ahuja, Bioinsecurities: Disease Interventions, Empire, and the Government of Species (Duke University Press, 2016).

More than a theory, kinship is a practice. While the list is too great to enumerate the practices of imaginative and subversive kinship that have informed my thinking and critiques, some luminary theoretical works include: Octavia E. Butler, Dawn, Xenogenesis (Warner Books, 1987); Heather Davis, Plastic Matter (Duke University Press, 2022); Donna Haraway, When Species Meet (University of Minnesota Press, 2008); Saidiya Hartman, Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Social Upheaval (W.W. Norton, 2019); Noriko Ishiyama and Kim TallBear, “Nuclear Waste and Relational Accountability in Indian Country,” in The Promise of Multispecies Justice, ed. Sophie Chao, Karin Bolender, and Eben Kirksey (Duke University Press, 2022); Ursula K. Le Guin, The Left Hand of Darkness, 25th anniversary ed. (Walker, 1994); José Esteban Muñoz, Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity, 10th anniversary ed (NYU Press, 2019); Kim TallBear, “Making Love and Relations Beyond Settler Sex and Family,” in Making Kin Not Population: Reconceiving Generations, ed. Adele Clarke and Donna Haraway (Prickly Paradigm Press, 2018), 144–64; Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing, The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins (Princeton University Press, 2015).

Jean-Luc Nancy, Being Singular Plural (Stanford University Press, 2000), 3. Emphasis in original.

See →.

The Holy Bible: Containing the Old and New Testaments, 1769 New King James Version (Thomas Nelson Publishers, 2006).

Lanford Wilson, Balm in Gilead, and Other Plays (Hill and Wang, 1983), 4.

Wilson, Balm in Gilead, and Other Plays, 20.

Richard Anderson, “Pharmaceutical Industry Gets High on Fat Profits,” BBC News, November 6, 2014 →.

Jocelyn Kaiser, “NIH Gets $2 Billion Boost in Final 2019 Spending Bill,” Science, September 14, 2018 →. As cited in David Mitchell, oral statement, The Patient Perspective: The Devastating Impacts of Skyrocketing Drug Prices on American Families, US House of Representatives Committee on Oversight and Reform, July 26, 2019 →.

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, Making Medicines Affordable: A National Imperative (National Academies Press, 2018).

A story about viruses and pharmaceutical capitalism told at greater length in Caitlin Berrigan, “Atmospheres of the Undead: Living with Viruses, Loneliness, and Neoliberalism,” MARCH, September 2020 →.

See →.

Dean Spade, Mutual Aid: Building Solidarity during This Crisis (and the Next) (Verso, 2020), 26.

As with Paul R. Ehrlich’s The Population Bomb (1968), there is a troubling whiff of the logics of eugenics in the ecologically motivated call to “make kin, not babies” in Donna Haraway, Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene (Duke University Press, 2016).

Gaia, a Way of Knowing: Political Implications of the New Biology, ed. William Irwin Thompson (Lindisfarne Association, Inc., 1987), 96.

Emily Klancher Merchant, Building the Population Bomb (Oxford University Press, 2021), 27.

See also Sophie Lewis, Full Surrogacy Now: Feminism against Family (Verso Books, 2019).

The concept “organized abandonment” is developed around the carceral logics of state-engineered vulnerability through organizational barriers to accessing basic resources in Ruth Wilson Gilmore, Golden Gulag : Prisons, Surplus, Crisis, and Opposition in Globalizing California (University of California Press, 2007).

David Wojnarowicz, Close to the Knives: A Memoir of Disintegration (Vintage Books, 1991).

“Sympoesis” is Donna Haraway’s elaboration of “autopoesis” as means to describe the mutual processes by which living things are sustained through regenerating systems. See Haraway, Staying with the Trouble, 33; Francisco Varela, Humberto Maturana, and Ricardo Uribe, “Autopoiesis: The Organization of Living Systems, Its Characterization and a Model,” BioSystems, no. 5 (1974): 187–96; Lynn Margulis and Dorion Sagan, What Is Life? (University of California Press, 2000).

Jack Halberstam, The Queer Art of Failure (Duke University Press, 2011).

On chronopolitics, see Alison Kafer, Feminist, Queer, Crip (Indiana University Press, 2013); Muñoz, Cruising Utopia; Ellen Samuels, “Six Ways of Looking at Crip Time,” Disability Studies Quarterly 37, no. 3 (2017).

Donatien Serge Mbaga et al., “Global Prevalence of Occult Hepatitis C Virus: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis,” World Journal of Methodology 12, no. 3 (May 20, 2022): 179–90.

Pier-Angelo Tovo et al., “Chronic HCV Infection Is Associated with Overexpression of Human Endogenous Retroviruses That Persists after Drug-Induced Viral Clearance,” International Journal of Molecular Sciences 21, no. 11 (January 2020): 3980.

Kjetil Bjornevik et al., “Longitudinal Analysis Reveals High Prevalence of Epstein-Barr Virus Associated with Multiple Sclerosis,” Science 375, no. 6578 (January 21, 2022): 296–301.

Berrigan, “Atmospheres of the Undead.” See also the many conflicts within Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha, Care Work : Dreaming Disability Justice (Arsenal Pulp Press, 2018).

See Fabian T. Pfeffer, “Multigenerational Approaches to Social Mobility: A Multifaceted Research Agenda,” Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, no. 35 (March 2014): 1–12.

US Senate Committee on Finance, “The Price of Sovaldi and Its Impact on the US Health Care System,” December 2015, 114–20 →; Andrew Hill et al., “Minimum Costs for Producing Hepatitis C Direct-Acting Antivirals for Use in Large-Scale Treatment Access Programs in Developing Countries,” Clinical Infectious Diseases 58, no. 7 (April 1, 2014): 928–36.

US Senate Committee on Finance, “The Price of Sovaldi.”

Édouard Glissant, as quoted in Manthia Diawara, “One World in Relation,” Nka Journal of Contemporary African Art 2011, no. 28 (2011): 4–19. This poetic concept is further developed by Fred Moten, The Universal Machine, Consent Not to Be a Single Being 3 (Duke University Press, 2018).

See Davis, Plastic Matter.

Subject

Acknowledgments: With much gratitude to the generosity of Samuel Hertz, Virginie Bobin, Eliana Otta, Miriam Simun, S. J. Norman, Perel, Meredith Bergman, and Eben Kirksey.