Increasing interest in organizing, structuring, documenting, and revealing the art history of the former Eastern Bloc is in large part attributable to artists who have participated actively in changing orders and elements within the visible, sayable, and thinkable, as Jacques Rancière’s definition of political art has it.1 Although heterogeneous in terms of formal proposals, the artistic projects that will be dealt with in this coming series have in common discursive aspects or forms of presentation that may be said to constitute “innovative forms of archives.” Such a phrase is at the same time deliberately ironic, as the notion of scientific or creative innovation is necessarily followed by the well-known support structures of presentation (exhibitions, events, and so on), within whose regimes and formats the Rancièrian redistribution of the sensible takes place. On the other hand, the projects discussed here do not only represent the strategy of self-historicization—one of the main correctives performed within an Eastern European institutional critique—but also contribute to the development of methods of artistic research and to theoretical endeavors imagining what, if anything, a shared history of European contemporary art might be.

Though an archive typically conjures up images of bookshelves, endless rows of boxes, folders, maps, and documents that sit waiting for scholars to discover and reactivate them, the term has a more flexible application within the context of critical writing. Sue Breakell has described an archive as:

a set of traces of actions, the records left by a life—drawing, writing, interacting with society on personal and formal levels. In an archive, the [single document] would ideally be part of a larger body of papers including correspondence, diaries, photographs—all of which can shed light on each other.2

The specific cases that will help us understand the objectives and mechanisms of archiving—not only in the former Eastern Bloc but also in the Middle East and in South America—typically employ the notion of the archive as a form, and find in this undertaking an argument for declaring the museum and the archive to be synonymous.3

Since the late 1980s, diverse motivations have inspired various forms of archives to emerge, such as Lia Perjovschi’s Contemporary Art Archive / Center for Art Analysis; IRWIN’s East Art Map; Tamás St. Auby’s Portable Intelligence Increase Museum; Vyacheslav Akhunov’s miniature reproductions of all his works in his installation, 1 m2; Walid Raad’s A History of Modern and Contemporary Arab Art; and various authorless projects originating in Southeastern Europe.4 Of particular interest in this regard is the project Museum of American Art in Berlin.5 Their practices have not only to do with the material found in examinations of the various personal and official archives, but also create a visual typology, offering material for further art historical research, while at the same time experimenting with the registers involved in the presentation and interrogation of documents and other archival material whose truth values are taken for granted in the course of aggressive and continuous media pollution; and finally they contribute to prominent discourses in contemporary art today on archeological procedures and the archeological imaginary.6 Such research might take the form of an artwork, an exhibition format, or a theoretical and art historical opus. In their presentation, they often become museum-like structures exhibiting self-institutionalizing agency, with all the accompanying knowledge produced, assembled, and transmitted to be used as a tool by an imagined or actual audience of specialists or a public. What these artists have in common is thus an adaptation of the profession of an archivist or art historian, thus gathering them under the designation “archival artists.” While Hal Foster’s description of artists focusing on found images, objects, and texts as making “historical information, often lost or displaced, physically present” would be logical here, it remains inadequate to the scale of these artists’ explicit historiographic and political endeavors.7 However, Foster identifies the main issue that separates artists-as-archivists from artists-as-curators:

That the museum has been ruined as a coherent system in a public sphere is generally assumed, not triumphally proclaimed or melancholically pondered, and some of these artists suggest other kinds of ordering—within the museum and without. In this respect the orientation of archival art is often more “institutive” than “destructive,” more “legislative” than “transgressive.”8

In the socialist and communist regimes, the official art apparatchik’s interest in and tolerance for experimental art production varied from country to country, thus leading the respective scenes to develop in various directions. Information, documentation, and other printed matter circulated among groups of like-minded critics, writers, and artists, and rarely entered the official art institutions. Meanwhile, artists and directors of experimental art venues continued to collect and compile documentation to the extent of their capabilities. By the end of the 1970s and throughout the 1980s, the increasingly liberating atmosphere of what could be called “the early attempts of civil society in a socialist state” went hand in hand with underground creativity, thus giving new life to much of this documentation, as well as a flowering of inter-generational links. In many of his writings, Boris Groys has examined the mechanisms of art collections, museums, or archives in the former Eastern Bloc, describing how the art was created in an ideological context and not within the logic of a market, as was (and still is) the case in the West.9 Instead of having their work incorporated in Western collections, the artists of the former Eastern Bloc, Groys concludes, have created imaginary or alternative “collection-installations,” histories and narrations that fill the entirety of museum spaces. In 2006, Zdenka Badovinac curated an exhibition at the Moderna galerija in Ljubljana that dealt with the artistic-archiving strategies in the former Eastern Bloc called “Interrupted Histories.” In the catalogue text, she established an important definition of the artistic process of self-historicization:

Because the local institutions that should have been systematizing neo-avant-garde art and its tradition either did not exist or were disdainful of such art, the artists themselves were forced to be their own art historians and archivists, a situation that still exists in some places today. Such self-historicization includes the collecting and archiving of documents, whether of one’s own art actions, or, in certain spaces, of broader movements, ones that were usually marginalized by local politics and invisible in the international art context.10

In the case of the Slovenian group IRWIN, this strategy was not explicitly critical, but existed in the form of a constructive or corrective approach. As Miran Mohar of the IRWIN group said with regard to institutional critique in the West, “how can you criticize something which you actually don’t have?”11 The main motto of Irwin in the 1990s was “construction of one’s own context,” and consequently the group itself functioned simultaneously as both observer and object of observation. This is the basis upon which we can think about the strategy of self-historicization, the artistic strategy that can furthermore be seen as one of the characteristics of an Eastern European institutional critique.12

Several years ago, Ilya Kabakov explained this artistic strategy of self-historicization as “self-description”:

the author would imitate, re-create that very same “outside” perspective of which he was deprived in actual reality. He became simultaneously an author and an observer. Deprived of a genuine viewer, critic, or historian, the author unwittingly became them himself, trying to guess what his works meant “objectively.” He attempted to “imagine” that very “History” in which he was functioning and which was “looking” at him. Obviously, this “History” existed only in his imagination and had its own image for each artist.13

Similarly, in his most recent book The Museological Unconscious: Communal (Post)Modernism in Russia, Victor Tupitsyn asks himself “what is to be done with art that has not realized its ‘museological function’ in time, even if this is through no fault of its own?”14 Tupitsyn finds egocentricity driving (Russian) artists’ increasing involvement in controlling both the selection of material as well as its interpretation: “they are attempts to reproduce the museological function (and even to replicate its institutional format) at the artists’ own expense and on their own terms.”15 Thus the egocentric strategy was activated as an alternative to the institutional mechanisms, to compensate for the lack of institutional support for unofficial artistic practices—a situation we encounter throughout the former Eastern Bloc, but also in the Middle East and South America.

While Tupitsyn’s view might be accurate when applied to the aspirations of neo-avant-garde artists, self-historicization is not always simply about egocentricity and paranoid control over one’s own body of work, which may otherwise not be properly documented, interpreted, and presented. The projects that will be presented here as case studies share a similar partisan spirit, one which can be conveniently explained using a notion with origins in online Open Access or Open Archives initiatives: self-archiving.16 Self-archiving involves depositing a free copy of a digital document on the Web in order to allow access to it, with these documents usually being peer-reviewed research papers, conference papers, or theses posted on the website of the author’s own institution. Formulating this notion within the broader context of knowledge production in general, self-archiving or innovative forms of archives help to raise questions of inclusion and exclusion, and of the right to think and to participate in restricted knowledge communities. Closely linked to this, and serving to differentiate between the chosen case studies, is an attention to their various fictionalizing or documentary capacities. The ontological status of the source and of the document as indices of authenticity is brought into the discussion, as will be seen in the cases of the projects of Walid Raad and the “authorless projects,” where fictional identities and invented documents playfully disturb canons of knowledge and histories previously considered as solid, unmovable rocks.

Lia Perjovschi: Contemporary Art Archive, 1990–

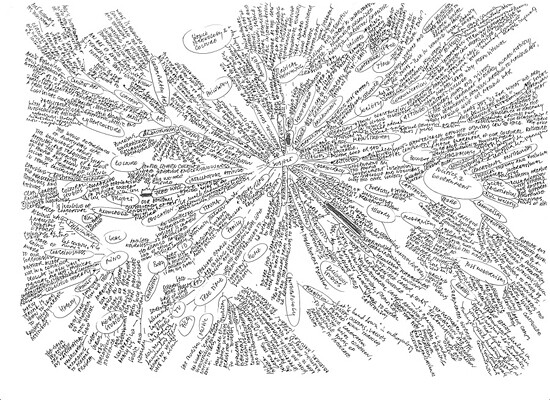

Starting with her performances in her Bucharest apartment in the 1980s, under one of the most repressive regimes in Europe, Lia Perjovschi’s activities created a space of resistance. From body art she switched to researching the body of international art, said husband Dan Perjovschi about the change in her practice. Her curiosity and desire to understand, recuperate, discuss, share, and coach found its way to a general audience. Her installations took the form of open spaces, discussion areas, reading rooms, waiting rooms, meeting rooms. Books, slides, photocopies, files, postcards, printed matter about international as well as Romanian contemporary art began to be organized and assembled in logical order. Lia also produced exhaustive drawings and texts aimed at compiling all possible information about the Western history of contemporary art, calling her products Subjective Art History.

After the revolution, in the early 1990s, equipped with unstoppable optimism and enthusiasm for the future, Lia and Dan used their studio to found the Contemporary Art Archive, a collection of magazine issues, book publications, and reproductions. By the end of the 1990s the CAA became a valuable database for alternative art initiatives everywhere, a self-supporting archive created outside the state funding network. Besides issuing cheaply designed publications meant to inform and to classify various art movements and tendencies on the basis of their archival material, the CAA organized several exhibitions paired with open discussions or lectures. In 2003 the CAA modified its function and has since operated under the title Center For Art Analysis. Lia describes herself as a “Detective in Art,” reading, copying, cutting, and remixing texts, concepts, and images. As Dan Perjovschi put it, “her Museum in files is not stuck on the shelves and is never closed … The knowledge of international art practice that she brought together helped to develop local criticism.”

Lia emphasizes the most important activity an archive can foster: sharing and teaching. While it was practically forbidden to share books, ideas, and information during the communist regime, she understood that a shared idea brings about another idea and that sharing is an essential survival strategy. This was certainly the case when Communism developed formal institutions that were so absurd that people avoided them altogether, replacing them with informal institutions (alternative economies and structures, the black market), strategies that continue to thrive as Post-Communist attempts at building faith through the mimicry of neoliberal models has proven neither promising nor trustworthy.

In the catalogue of the exhibition “Again for Tomorrow,” organized by the MA

curatorial students at the Royal College of Art in London and featuring the artists of the Buenos Aires artist cooperative Trama, Claudia Fontes, who founded Trama in 2000, speaks of the survival strategy that stimulates one to build an archive in a context where memory is under constant threat:

When an archive’s latent content is organised and distributed through a network-like structure, a powerful potential is unleashed. Transparency and a willingness to share information gives rise to trust, and trust is known to be the basic condition that keeps any network alive.17

Claudia Fontes points to how Perjovschi went from total mistrust to building up a powerful matrix of knowledge to be shared and updated through a process of ongoing

discussions, lectures, exhibitions, and exchanges. Fontes also points to a further comparison with Graciela Carnevale’s archive of the Grupo de Arte de Vanguardia de Rosario, started in the late 1960s, finding in both of these examples evidence of resistance in which a notion of archiving becomes a survival strategy, even in very different political (and authoritarian) contexts.

In the past few years, Lia has been working on and exhibiting Plans for a Knowledge Museum, an imaginary museum based on files accumulated over her years at the CAA. Characterized by an interdisciplinary approach, this future artist-run museum is dedicated to moving away from the logic of the exhibition-as-spectacle, and towards a learning process of working with an open-structured archive. Installation of these Plans for a Knowledge Museum comprises drawings, objects, charts, photos, and color prints. This material is there for viewers to hold and make use of, much like the notion of self-archiving mentioned above. As we will see in the next installment, this attitude of openness also corresponds to the aspirations of IRWIN’s ongoing project East Art Map.

Jacques Rancière, The Politics of Aesthetics: The Distribution of the Sensible, trans. Gabriel Rockhill (London and New York: Continuum, 2004), 63.

Sue Breakell, “Perspectives: Negotiating the Archive,” Tate Papers 9 (Spring 2008), →.

The many archival approaches coming from South America will be the object of future research but cannot be specifically discussed here. For more about archive as form in contemporary art, see Okwui Enwezor, “Archive Fever: Photography Between History and Monument,” in Archive Fever: Uses of the Document in Contemporary Art, ed. Okwui Enwezor (New York: International Center of Photography; Göttingen: Steidl, 2008), 14–18.

The term “authorless projects” for this very specific assembly of projects and exhibitions is used by Inke Arns, who curated the exhibition “What is Modern Art? (A Group Show)” at the Künstlerhaus Bethanien in 2006 and edited together with Walter Benjamin the catalogue What is Modern Art? Introductory Series to the Modern Art 2, (Frankfurt am Main: Revolver, 2006).

Another important example, which is however omitted from this essay, is Polish conceptual artist Zofia Kulik, who has in several recent projects been arranging and exhibiting the archive of the Laboratory of Action, Documentation, and Promotion—PDDiU. This was an archive managed by the artistic tandem KwieKulik (Zofia Kulik and her then partner in life and art, Przemysław Kwiek) and maintained in their houses. For more on archiving strategies in Zofia Kulik’s body of work, see Luiza Nader, “What Do Archives Forget? Memory and Histories, ‘From the Archive of Kwiekulik,’” in Opowiedziane inaczej. A story Differently Told: Tomasz Cieciersk / Jarosaw Kozłowski / Zofia Kulik / Zbigniew Libera i Darek Foks / Aleksandra Polisewicz (Gdańsk: Centrum Sztuki Współczesnej Łaźnia, 2008), 84–122, available at →.

See Dieter Roelstraete, “The Way of the Shovel: On the Archeological Imaginary in Art,” e-flux journal, no. 4 (March 2009), →.

Hal Foster: “An Archival Impulse,” October 110 (Fall 2004), p.4.

Ibid, 5.

See for example Boris Groys, Logik der Sammlung. Das Ende des musealen Zeitalters (Munich: Carl Hanser, 1997).

Zdenka Badovinac, “Interrupted Histories,” in Prekinjene zgodovine / Interrupted Histories, ed. Zdenka Badovinac et al. (Ljubljana: Museum of Modern Art, 2006), unpaginated.

Private interview with Miran Mohar, 2006.

See Nataša Petrešin, “Self-historicisation and self-institutionalisation as strategies of the institutional critique in the Eastern Europe,” in Conceptual Artists and the Power of their Art Works for the Present, ed. Marina Gržinić and Alenka Domjan (Celje: Center for Contemporary Arts, 2007).

Ilya Kabakov, “Foreword,” in Primary Documents: A Sourcebook for Eastern and Central European Art since the 1950s, ed. Laura J. Hoptman and Tomáš Pospiszyl (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 2002), 7–8.

Victor Tupitsyn, The Museological Unconscious: Communal (Post)Modernism in Russia (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2009), 230.

Ibid, 230.

In an e-mail conversation, Sven Spieker, author of an influential book examining the archive as a crucible of twentieth-century art—The Big Archive: Art from Bureaucracy (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2008)—suggested an umbrella-term, “self-archive,” for the cases discussed in this very article.

Claudia Fontes, “London Calling,” in Again for Tomorrow (London: Royal College of Art, 2006), 129.

→Continued in issue #16: “Innovative Forms of Archives, Part Two: IRWIN’s East Art Map and Tamás St. Auby’s Portable Intelligence Increase Museum.”