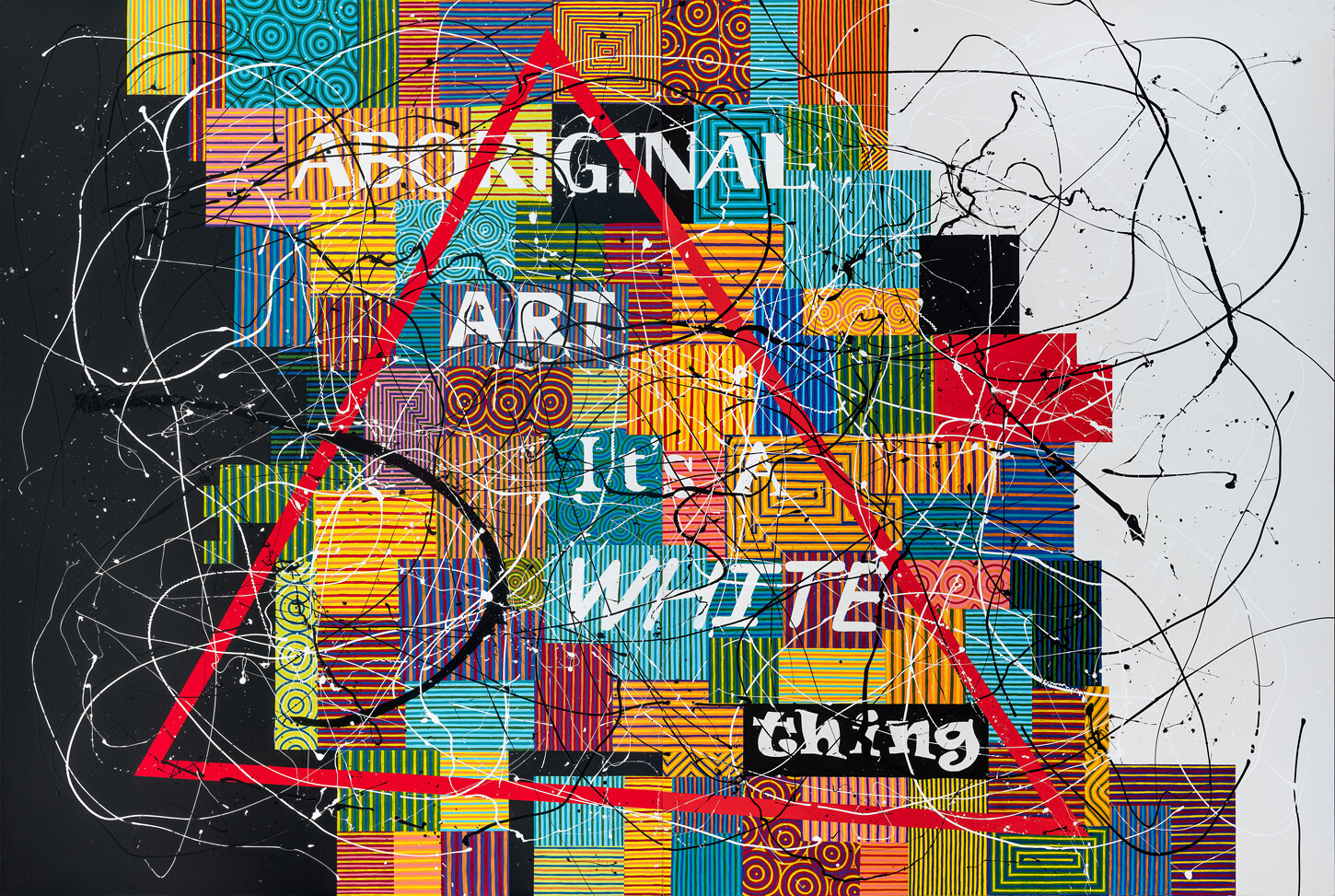

This essay, written in April 2022 shortly before the opening of documenta fifteen (in which Bell was a participating artist), was commissioned on the occasion of Richard Bell’s exhibition “RELINKING” (June 25–December 4, 2022) at Van Abbemuseum Eindhoven. The exhibition features statement paintings accompanied by two essays by Bell on the position of Aboriginal art and artists in the art world. This is the second of those two essays. The first is “Bell’s Theorem: Aboriginal Art—It’s a White Thing!,” a landmark text originally published in 2002 and reprinted by e-flux journal in April 2018.

—Editors

My painting Scientia E Metaphysica (Bell’s Theorem), or Aboriginal Art: It’s a White Thing, won the 20th Telstra National Aboriginal Arts Award in August 2003—it was an important moment in many ways. The accompanying essay, “Bell’s Theorem: Aboriginal Art—It’s a White Thing!,” was written to come to terms with my position in Contemporary Art, given the aesthetic prejudices against urban Aboriginal artists and practices and the persistent white hold on, and ignorance of, our power. There wasn’t a position, so I made one. I’d moved away from activism in 1992, the year of the Mabo court case, which marked the beginning of the defeat of the political possibilities of a national, pan-Aboriginal land rights movement. Mabo reexamined the absent legal foundations of the British invasion of what is now Australia.1 One of its main outcomes was an extremely weak “cultural” category of Indigenous land title called “Native Title,” made up entirely out of thin air, to placate the case for land rights. My essay aimed to just map out, for a settler-dominated art institutional landscape, the direct links between the ongoing white control and exploitation of Aboriginal identity by the “Aboriginal” art market, and the pernicious “divide and rule” impact of post-Mabo Native Title legislation, which had already taken its hold of our people, and, I still argue, strongly constrains white imagination. In the intervening years, “Bell’s Theorem” has pretty much held up as a manifesto for my art practice. It came from discussions over decades with Aboriginal people not just about art, but culture, life, politics, everything—the actual situation we are in.

Around the time of “Bell’s Theorem,” the politics of fine art was beginning to recede from public debates and was replaced by a flat-out race war, which dominated the scene in Australia as elsewhere from 2001, continuing up to and beyond the 2008 global financial crisis. A conservative prime minister, John Howard, had clung to power by accusing Muslim refugees of throwing their children into the sea whilst seeking asylum. The Australian government had already built refugee detention centers in the desert that resembled concentration camps. After the “children overboard” affair, it embarked on the Pacific Solution, which was to dump these people unlawfully and indefinitely onto remote Pacific islands in detention prisons. Many of these people are still there, living the hell of offshore terra nullius, twenty years later. The Yorta Yorta case was the major Native Title decision around that time and it was a whitewash, the judges imagining the “tide of history” had “washed away” people’s laws and customs. I reckon you could track that history of manufactured race wars against actual land grabs through the rise and fall in Aboriginal Art sales, but not many people think about it in this way.

An Aboriginal Critique

To the Australian art world, and its broader public, what was shocking about “Bell’s Theorem” was that it showed how badly positioned our work was, given that the total number of sales of Aboriginal Art was ten times the number of non-Indigenous Australian art sales internationally. Also for value of sales, Aboriginal Art just monstered the sales figures of non-Aboriginal artists. It was bigger, better, and far more significant than the non-Indigenous Australian art scene, which had never happened before in any of the Anglo colonies. As late as the 1980s, when national Aboriginal land rights were still a political possibility and had unprecedented support from the Australian people, 80–90 percent of Aboriginal Art was still going overseas and was hardly being collected by Australian art institutions. The prices of individual works by painters like Emily Kngwarreye and Rover Thomas were going through the roof. So it was shocking to people that there was so little Aboriginal control, and so little benefit, or return of value. It was an entirely unspoken and unspeakable reality up to that point. And it went against all the white fantasies of pomo reconciliation that the Australian art world and the legal establishment, the museums and Mabo, were aiming at to mystify their dominance.

Art was always a part of what we were reclaiming as our rightful, stolen inheritance. It was and is inseparable from the maintenance of our culture and economies. Without getting our land back, our culture—which was illegal to practice—is everything, is all we have. Right up until the 1960s and ’70s, many Aboriginal people who were wards of the state had to ask the permission of welfare and missionaries to buy or sell anything worth more than ten pounds! That kind of thing is why the everyday extractivism and selfishness of the art world we put up with is just so painful, pointless, and banal. It is a banal missionary culture we experience a lot of the time when white curators and institutions think they are inevitably helping us, when merely offering us professional opportunities for our projects. When Redfern activists Billie Craigie and Cecil Patton stole the paintings of Yirawala from a commercial “Aboriginal” gallery run by a white man in Sydney on a mischievous night in 1979—important paintings by an important Arnhem land artist almost wholly under the control of a white woman—their defense was that since they were Aboriginal, and the paintings were Aboriginal-community owned, they believed they could take them legally to protect them, and they won the case.2 That is the kind of political solidarity and nonaligned imagination that was totally eviscerated by Native Title.

See the essay by Aboriginal Black Power historian Gary Foley, Native Title is NOT Land Rights (1997) →.

Australia was the first officially white-supremacist nation in the world.3 The genocide was unceasing, and legal until the twenty-first century.4 When the country “internationalized” its economy via US state power through Southeast Asia from the 1950s and ’60s, it still paid poor colonial attention to Aboriginal Art practices, “traditional” or otherwise. The inaction and backwardness of the major Contemporary Art organizations in the areas of collecting and displaying work, in taking a genuine interest in Aboriginal people, was a disgrace. It took land rights and the activism of urban Aboriginal artists for the inattention of settler art institutions to be too obvious to ignore. Arguably, the peak of the Aboriginal control of Aboriginal Art was not 1995 or 2020, but 1975, when the first state-sponsored Aboriginal Arts Board had a majority of fifteen Aboriginal members. They favored outreach collaborations and mobile production units, educational training and touring, black film and black theater, not replacing traditional forms but engaging grassroots people in the topical issues of the day and in the media forms directly affecting them. We knew we needed art and we had sophisticated media tactics. That’s how I became an artist—I learned how to use the media when numbers are not on our side, which they are never. We are 3 percent of the population, and the majority of us live in the cities far away from our rightful territories, so decolonization in the way it was defined and strategized by the Algerians was just not an option.

After three years of running the place, the Aboriginal Art Board was disbanded. Sotheby’s set up its “primitive” art department in London in 1978, and later an auction house in Australia, but the national impact of those years was significant, impacting multiple generations. As I wrote in “Bell’s Theorem,” “the Dreamtime is the past, the present and the future … The Dreamings pass deep into urban territories and cannot be complete without reciprocity between the supposed ‘real’ Aboriginals of the North and the supposed ‘unreal’ or ‘inauthentic’ Aboriginals of the South.” The main brake on these crossings of solidarity, which are material (it was shared ecosystems and people’s lives that we were defending!), was always the colonial project. “Bell’s Theorem” named its cultural arm: the ethnographic approach to Aboriginal Art, the authority of anthropologists, the tendency of Westerners to classify the shit out of everything for them to make their world picture, the hidden exploitation of “remote” art centers, and the clear capitalist tribal order that ranks white specialists as more knowledgeable on Aboriginal Art and identity than Aboriginal people themselves.

Anthropology Regained?

Today, many Aboriginal people are confused as to why white anthropologists continue to be asked to adjudicate the value of our practices in art spaces internationally. After 250 years of extraction, sixty-plus years of Aboriginal Art being treated seriously by art historians (despite their limited authority for judgment), and just a few decades of Aboriginal-curated exhibitions, the time for white experts to be forging “practical” careers upon our land rights struggles in this transition to neoliberalism is nearly coming to a close (because the claims themselves have been intentionally limited to a fraction of the total land base). When I wrote “Bell’s Theorem,” anthropologists were entirely up our arses. Europeans today seem to think anthropologists must have all decolonized because the reckoning itself was so necessary. Given that their employment and colonial power of interpretation over our people, lands, and families only shifted from art into law in the contemporary era, with great consequences of land loss as part of the land rights legislation, how could this have been possible? Aboriginal people can’t turn up to a land court and have our rightful claims heard without the verification of some white scholar from Sydney, New York, or Melbourne. That is the reason anthropologists are still on our land. The onus should always have been on white title holders to argue for their occupation of our land under claim.

What we now know was that Mabo and Howard’s Ten Point Plan is what neoliberalism looked like in the South. To Europeans and settlers, neoliberalism was about wage freezes and privatized infrastructure, the sell-off of public assets, utilities, and housing. In the South and on Indigenous-governed lands, calls for decolonization were not just calls for self-determined politics but also an attempt at countering the violent and increasing reach of multinational capitalists, miners, and agriculture. The restructuring of the global economy, which Mabo was both a part of and a distraction from, made it more possible for more kinds of non-Indigenous capitalists to make more diverse kinds of profits from more differentiated kinds of leasing agreements on our lands. The scale of that diversification of capital is far more significant in keeping power unbalanced than the diversity initiatives of art institutions to “correct” such imbalances. What “good governance” in Australian art organizations usually means is what the Business Council of Australia requires for itself.5 A next generation of land activists such as the SEED Indigenous Youth Climate Network6 and the Warriors of the Aboriginal Resistance7 fights against major pipelines and energy companies in struggles as significant as Standing Rock, and includes many artists. There is no comparable level of attention from the local or international media to this situation. The increasingly blatant influence of corporate power, apart from producing an ever-expanding sphere of intervention into Indigenous lands, ecosystems, and peoples’ agency, offers up just ever-more fragmentation. There is no community, no politics, no solidarity, and no debate in this dominant business culture at all. The Australian Dream of one nation under private property and debt, with a few tax breaks for art appreciation, is a nightmare for my people and it is what continues to do us all in. Tell them they’re dreaming.

Against Art Industrial Assimilations

The Western hold on Art and cultural critique is not just a problem for art, it is a problem for the way we can think about culture as a space of survival, imaginative thinking, and responsibility. Museums are loot rooms to colonial patriarchy and white welfare nationalism, and yet when we take a serious look at their cultural power they are also very naked. We may engage with them or walk away from them, but they are some of the last semi-public spaces where cultural practices and debates are not entirely under corporate control, or entirely subjected to entertainment principles (though this is debatable in Australia). We can use words like “decolonization,” “demodernization,” “rematerialization,” “feminism,” and so on to describe a position or practice. But only a genuinely nonaligned art movement defecting from the status quo can deal with these things systematically, genuinely, and cooperatively as very unevenly shared problems.

In response to “Bell’s Theorem,” there was no real capacity of Australian or international institutions to begin to deal with the critique. If you listen to the establishment’s version of history covering the successful “inroads” of Aboriginal artists into the Australian art world over the last decades, you will hear that we have all come to a place of being taken seriously by institutions and critics, that Aboriginal artists and curators are everywhere, and so on. Some will even say our work is the most contemporary! The end. Of course, we have been collected. There are now two generations of Aboriginal curators, working since the 1980s and 2000s. Institutions are dependent now upon their Aboriginal Art collections for their value propositions. Indeed, they have to put the Aboriginal Art right at the back of the institution to force visitors to walk through the white art first, because if the Aboriginal Art was up front they would walk in, see that, and piss off. But the institutions still exhibit an extremely limited capacity for both internal and external critique, even just at the level of any singular project. They are entirely nontransparent in the actions they take that directly affect Aboriginal community politics and Indigenous art histories.

Right now, the space of criticism in Australia has never been more conflict bound, racially charged, intellectually limited, and therefore borderline irrelevant. There is an increasing illiteracy of gallery directors, writers, and curators in geopolitics and in sophisticated non-Western art debates. Because of the full impact of Native Title and corporate governance in wreaking conflict and havoc on Aboriginal community and self-determination possibilities, we do so much work just trying to keep things together, while the art organizations cherry pick for winners and lone rangers. In the absence of institutions and curators—Indigenous and non-Indigenous—taking stronger intellectual positions in the field, even more pressure gets put on my people to be the only angry ones. We are left with the task of educating the audiences of institutions that show no long-term commitment to our histories, because they truly don’t understand or recognize how much they would benefit from our liberation, beyond myopic claims on our practices that constitute little more than window dressing.

To be an Indigenous artist who moves through Europe amid an almost nonexistent contemporary discourse for our work there is very hard. We need to have Indigenous curators working abroad. At the same time, the ones that are most committed to our communities have no reason to be “based in Berlin.” However, it is unfortunate that few Indigenous curators can take critical opportunities to leave the domestic scene to absorb other geopolitical realities, away from the cultural and political vacuum of assimilation agendas, which are unceasing. BANFF used to be a place for this kind of discussion—that’s where I worked with Brenda Croft, Megan Tamati-Quenell, Margaret Archuleta, Leanne Martin—which created so many amazing opportunities for many Aboriginal artists. In the absence of meaningful, educated, informed infrastructures for our work, white curating self-reproduces its own expertise through our supposedly civilizational “difference.” They will never engage enough with our strongest and most geopolitically minded artists, activists, and curators. This situation will certainly continue.

Our people are always looking for messages coming out of the arts. Even if they don’t understand Contemporary Art as a whole, they know that we have to be there. There is a class dimension to how the work gets shown, not just due to the dynamics of settler capitalism, but because there is a specific class dimension within Aboriginal society that is allocated and exacerbated by Native Title legislation. Tragically, this is seldom understood. What’s also tragic is when people think you make millions from political platforming practices—when really it is a matter of speculative expenditure. How much cash do you choose to blow on something in order to get a meaningful result and impact that you can live with? These are the realities that face an artist making political art which comprises just 4 percent of total sales in the art market. Urban Aboriginal Art would be the tiniest portion of that.

Extinguishment’s Place-Making

The Australian museum system and art gallery system has paid lip service to urban Aboriginal Art since the 1990s, but it is only through our outspokenness and our support of each other, including through all-Aboriginal collectives, that we have gained the space to show our work and some degree of notoriety. Institutions are afraid to invite us in as self-determined collectives. And there is almost no understanding still of why we needed and still need to organize like that, in the non-Aboriginal urban art world, because there is such limited understanding of the relationship of Indigenous art histories to the control of people across space, in an international perspective.8

When art professionals do not understand the regional, global, and family histories of our movements, they easily repeat the divisive favoring of “A team” Aboriginal assimilationist players over the long history of B team commitments and operations. What was the A team? The A team aimed at Western legal solutions to only-cultural recognition. They gave up on our demand for land rights as a political and economic problem that still haunts us, and that increasingly haunts white people also trying to defend our lands and waters from predation. They turned us into a cultural development art of the state and limited our future legal possibilities to the benefit of a small number of already legally empowered communities. They eliminated real reparations and anything close to black radical or abolitionist politics from our demands, for an obsession with constitutionalism that is entirely favored by transnational corporations. The Howard-style con job of the Statement from the Heart already happened years ago in Eva Valley.9 (Most blackfellas know fuck all about the Statement from the Heart, for reasons that should be obvious. But they will be as disappointed by the outcome as they were then, maybe more so.) This is not “personal” critique—what continues to divide our people is part of a global regime of control and assimilation—it is no different to what is happening to Indigenous and racialized peoples’ movements in wanted territories all over the world. Domestically, we write and acquit decolonial art project grants according to evaluation criteria for beauty and community set by the cultural policy of the RAND Corporation.10 No one bats an eyelid about this. This is wholly connected to the problem with reading our finest art practices through political minimalism—the ease of alignment with any neoconservative agenda available. But this is seemingly no concern for settler cultural industry workers, or they would speak up about it. They don’t seem to even notice.

It was only through the global financial crisis that the neoliberal consensus was broken in Contemporary Art, though that never happened in Australia.11 In the US, artists and activists connected the crisis of subprime mortgages to histories of redlining, as an exorbitant amount of wealth was extracted from black families. In Western Europe, liberal institutions belatedly dealt with the populist right by giving space to Marxist and feminist critiques of capitalism for the first time in decades. The communist horizon was revisited, while artists from the Former East also addressed entanglements with imperialism and colonialism. There was a more general recognition that the postwar good life, white and assimilationist, was unravelling. In Australia during this period, a large-scale Intervention into remote Aboriginal homelands rolled back years of flailing self-determined policy agendas and Indigenous-led land reform, while citizens were told the mining boom saved them from the global financial crisis (which was impossible, because the profits aren’t kept in the country—only 15 percent of mining interests are Australian owned). A persistently conscientious corporatism has left no space for a shared, let alone intersectional, understanding of art’s actual conditions of production beyond a neoliberal multicultural agenda that is traumatizing for almost everyone because it is so devastatingly meaningless.

Art institutions today seem to prefer to focus on the problem of extinction over the problem of capitalism. Precisely by not connecting these, they limit their relevance. There is no fear of the damage of such conservatism in daily institutional decision-making. Directors and curators update themes, and try to invite more diverse artists to the performances and parties, but the mode of production is exactly the same. Some artists are doing double the work through practices that do not perpetuate colonial modernity, but without major turns at the level of direction and organization, our best interventions become sensational and singular, almost in spite of what they actually are. A just-in-time mode of production and a lack of understanding and respect reduces our work to just another commodity, sold up to whiteness. Meanwhile, capital’s hold on the real and the possible, in and outside of art, continues apace. When Occupy Wall Street was accused of itself occupying the lands of the Lenape (the original Indigenous people of Greater New York), it was a teachable thing that happened for the urban left in New York City. We need that kind of literacy at the center of Empire and at the frontiers, shared between all kinds of people. Instead, we have manufactured identity wars watched over by very poorly educated urban settler cultural industry professionals, who have no idea how to reproduce anything that matters.

The Limits of Ethical Consumption (More Ooga Booga)

Europeans love nothing better than to indigenize their racist humanism when they themselves are in crisis—it is one of their most dearly loved moves (all of the Enlightenment guys did it, not to mention the modernists). While the Western world has now fully penetrated the globe with their model of universal competition, the political economy they’ve violently assigned our communities cannot address the situation that any of us now face together. There is no more planet or time left. An Indigenous and nonaligned conversation about genuinely independent and collective politics is what was always needed. We also need to remember that the very concept of comparative civilizational recognition is a white thing.

Consider, for example, the gargantuan problem that some of the most ornate, land-based forms of Australian Indigenous paintings today—paintings which testify to the intergenerational resistance and survival of peoples, their intimate ancient knowledge and maintenance of lands, waters, and songlines—are so freely offered up as nonpolitical consumption to the most colonial and neo-imperial Art Institutions globally. People still misread the urban Aboriginal artists’ critique of what we call Ooga Booga. Ooga Booga is not a critique of land-based or “traditional” practices. Ooga Booga is not even the work itself. It is what is cultivated and harvested by the white traders. It is the market niche that attaches spirituality as supplement to the work, although what is sacred has already been shielded away by the artist and community. The real magic of the important knowledge is not given over to the buyer, but this point is academic. It is the white-managed fantasy of access to our very being that they want. In France, Germany, the Netherlands, New York, they will always want painting, weaving, dance, and sand drawings, but the appetite for our spirit in the absence of a critical curatorial and noncoercive economy participates in a broader depoliticization and aestheticization of all of our practices. Europeans want the finest work, of course, to be viewed in a vacuum, shielded from the rest of humanity, and even from their capitalism!

The fact that art remains relevant in this voracious stage of unlimited total production is indeed a testament to art’s power. But what we get, what the public gets, are the most easily commodified forms, viewed through Western minimalism still. Such curation says nothing about our struggles to maintain life against our disempowerment. The unprecedented “Aratjara” exhibition was cocurated to tour Western Europe by land rights activists in 1993.12 “Aratjara” was one of the most important, collectively deliberated, large-scale, Indigenous-curated exhibitions seen anywhere. Each work across all media stayed attached to a rightful argument about our different land relationships within the group, but that show is almost always missing from the international exhibition histories preferred by white art historians. The few places that collect urban Aboriginal practices in Europe update their representations to be “inclusive,” but they rarely upset the broader ethnographic system that essentializes us ahistorically into place.

When we insist on our inter-nationalism, our solidarity and communal traction, shared professional commitments to the field of “Culture” might involve more accountability. What Aileen Moreton-Robinson called “white possession” will always be in the room.13 So the question is—whether you are in an artistic, curatorial, academic, or managerial position—how are you going to respond to the real generativity, the serious generosity of the call for accountability that is coming from the nonwhite position and from artist groups? “You scratch my back, I piggy-back on yours” is not a very edifying professional experience for any of us. Can the traffic in Aboriginality that non-Indigenous spaces profit and benefit from—indeed can’t do without in the Anglo colonies, despite no returns of value or profit to our communities—can it ever be deployed otherwise? Based on the last forty years, perhaps not. Or at best, rarely so. Much more often, revisionist takes on our history and practices do deep colonizing damage, wittingly and often unwittingly, offering little to nothing on the side of a broader collective sense of well-being.

Reductio ad Infinitum

Documenta is a marker for Europeans of their turn away from race, but not their racial entanglement with the Global South and East. What actually occurred in the so-called “postwar” era was a switch towards gross national product as the measure of all things. You can’t celebrate doing away with fascism while maintaining global capitalism. The postwar biennial space is a good thing, but looking inwardly, all the Europeans can see is themselves. Outside that whiteness, the rest of the world isn’t. The fact is, 90 percent of the world’s population is not white. But this is not reflected in the art market. There may never be a reckoning, because of the simple fact that the art market is driven more by the need to avoid regulatory control and taxation (of “whatever”) by sovereign states, than by any historical focus or literacy. New terra nullius zones like freeports, designed specifically for lawless art operations, are built in direct response to the climate crisis, while carbon smokes from the NFTs.14 The market attention has moved through Africa, Asia, and the Middle East, through blackness, but this is a calculus, and Indigenous Art is next to have its moment. It’s presented now as contemporary, but it will still be “a white thing.”

Documenta fifteen is not going to look like any other previous iteration and the usual audiences may well find it difficult to navigate. They may feel under attack, or affronted to not be able to recognize themselves or their cultures. How will they react to the multitude of issues and ideas unleashed by such unfamiliar practices? The previous documentas and the Berlin Biennales of the past were just a precursor to this, and shows like “Diversity United” may be used as a bit of a distraction from it. There will be many unrecognizable names that have never been in a prestigious biennial before, and certainly never shown in a major institution. It is the fault of the institutions, and the curators, that they haven’t been able to find these people. Questions need to be asked. Why have the museums and curators not been able to find them? Why have these artists been ignored? The reason is clear, Contemporary Art is a white thing.

As I write this, a major and important exhibition of Aboriginal songlines from the middle of the desert of Australia will soon be showing in Plymouth, the port of Cook, before heading to the Musée du Quai Branly (so blatantly anthropological and primitivist), and landing inside the gargantuan Prussian Palace of the Humboldt Forum, one of the most neo-imperial museum projects of the twenty-first century in Western Europe.15 When ordinary Germans see this kind of important show in that kind of place, that is the kind of show that is presented to them as Aboriginal, and only that kind of art is the kind of art that they will be looking for in the future. How do we deal with this kind of aestheticization and depoliticization of really significant practices? This is a project driven by progressives, and conservative institutions have grabbed it and will turn it into a neo-ethnographic experience. They are pretending to care for our culture and knowledge but will take no interest in the Apartheid situation. It speaks to the lack of literate venues for complex contemporary work, and to the central fact that even when Aboriginal Art is assumed to be contemporary, it is ghettoized and essentialized as a white thing. I don’t believe this institution has the capacity to enact a duty of care for this exhibition. Rest assured, the Humboldt will not be the only major institution to stage shows like this. To be very, very clear, this is not a criticism of the exhibition, but of the venue, and of the kinds of institutional entanglements we have to deal with. It is a judgment on the unworthiness of the Humboldt to hold it.

I believe that in the next decade or so, as the hunger for Indigeneity, for ecology, for a new black market of unfamiliar “Indigenous Art” practices becomes more widespread, that the most popular work on the market will be the least political, the least offensive, and the least critical. The market will choose the winners. It will try to wholesale ignore the most outspoken and dispossessed people in my country, rendering the most critically engaged Contemporary Art the least valued. Gagosian Gallery has already tipped its hand with two Emily Kngwarreye shows and we have Steve Martin as an overnight “influencer.” The direction they are taking is a familiar one. It always starts out and finishes in the same way. The market will continue to exoticize to destroy Aboriginal and Indigenous peoples and lands globally, and the art market will be a frontline.

No land, no compensation, just an easily ignored voice.

Hope less. Do more.

Gary Foley, “Native Title Is Not Land Rights,” Kooriweb, September 1997 →.

David Weisbrot, “Claim of Right Defence to Theft of Sacred Bark Paintings,” Aboriginal Law Bulletin 1, no. 8–9 (1981) →.

The first act of the new Australian parliament was the Immigration Act, otherwise known as the White Australia policy. There was no mention of Aboriginal people in the constitution. See Irene Watson, Aboriginal Peoples, Colonialism and International Law: Raw Law (Routledge, 2014).

Watson, Aboriginal Peoples. See also Irene Watson, “There is No Possibility of Rights without Law: So Until Then, Don’t Thumb Print or Sign Anything!” Indigenous Law Bulletin 5, no. (2000) →; and Aileen Moreton-Robinson, “Virtuous Racial States: The Possessive Logic of Patriarchal White Sovereignty and the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples,” Griffith Law Review 20, no. 3 (2011) →.

See Lindy Nolan, Driving Disunity: The Business Council Against Aboriginal Community (Spirit of Eureka, 2017) →.

SEED is Australia’s first Aboriginal youth climate network →.

Brisbane Blacks, “Warriors of the Aboriginal Resistance: Manifesto,” November 24, 2014 →.

Slavery is almost never associated with black Indigenous politics in Australia. We had slavery until the 1970s in some areas, and our movements were in conversation with black internationalism from early days. See John Maynard, “‘In the Interests of Our People’: The Influence of Garveyism on the Rise of Australian Aboriginal Political Activism,” Aboriginal History, no. 29 (2005).

“Update August 1993: Eva Valley Meeting. 5th August, 1993,” Aboriginal Law Bulletin 3, no. 63 (August 1993) →.

For the RAND Corporation, see →.

See Rachel O’Reilly and Danny Butt, “Infrastructures of Autonomy on the Professional Frontier: ‘Art and the Boycott of/as Art,’” Journal of Aesthetics & Protest, no. 10 (Fall 2017) →.

“Aratjara” translates as “messenger” from the Arrernte language. See the catalogue Aratjara: Art of the First Australians: Traditional and Contemporary Works by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Artists (DuMont, 1993).

Aileen Moreton-Robinson, The White Possessive: Property, Power and Indigenous Sovereignty (University of Minnesota Press, 2015).

Talia Berniker, “Behind Closed Doors: A Look at Freeports,” Center for Art Law, November 3, 2020 →.

Noëlle BuAbbud, “Nightmare at the Museum: An Interview with Coalition of Cultural Workers Against the Humboldt Forum,” Berlin Art Link, February 5, 2021 →.

Subject

Edited by Rachel O’Reilly