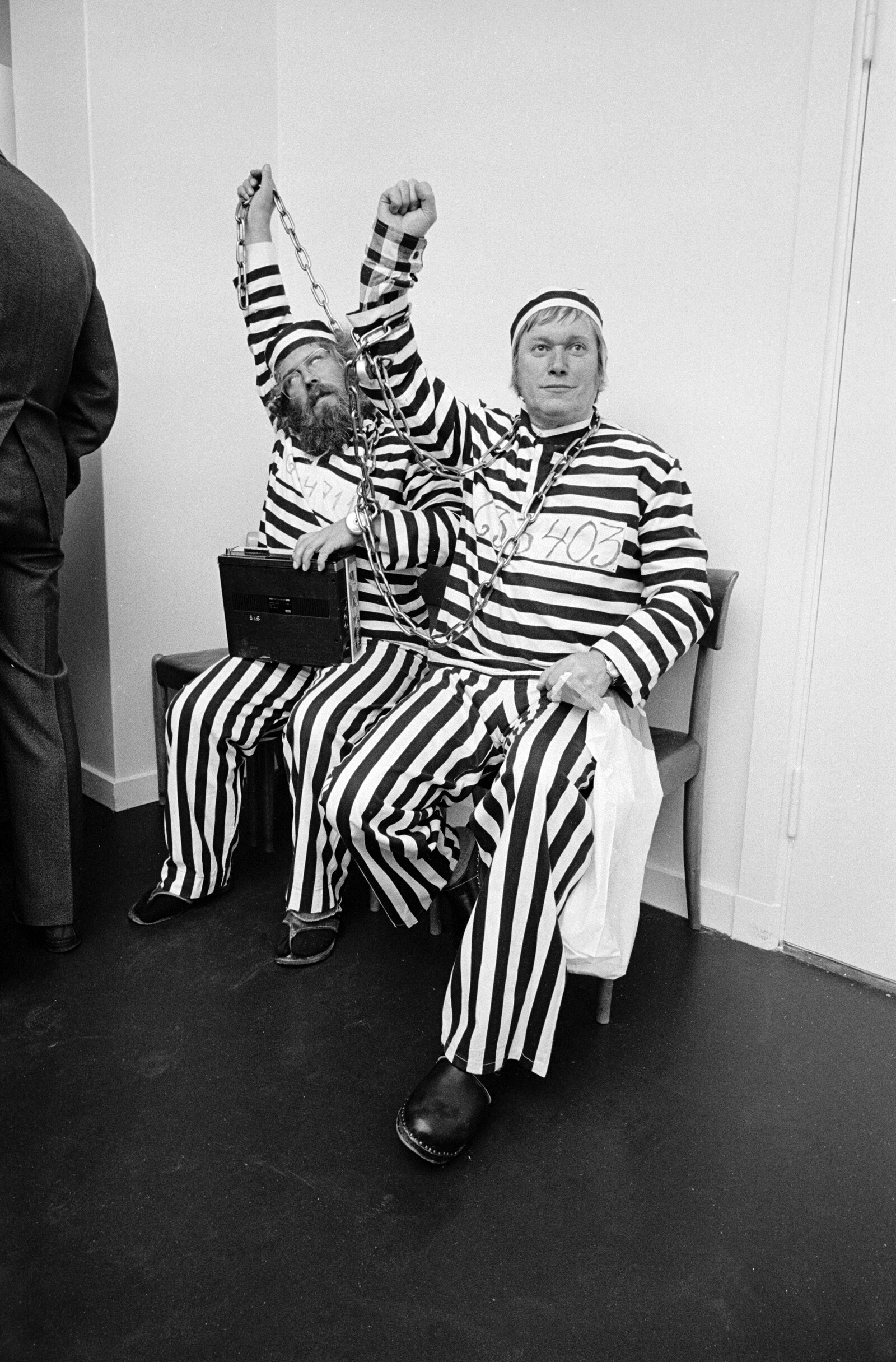

Jørgen Nash and Jens Jørgen Thorsen dressed up as convicts before going to court, 1975. Copyright: Aller Media/MEGA. Photograph: Morten Langkilde/Ritzau Scanpix.

The current Nashist detail is only an epiphenomenon. No doubt its successors will be stronger.

—Guy Debord, “The Counter-Situationist Operation in Diverse Countries,” 1963

Today, there are more and more individuals who are declared insane, and more and more actions that are considered crazy. But the only place on earth that has so far been regarded by the cosmo-polis or in public mythology as the land of lunacy is Scandinavia.

—Asger Jorn, Things & Polis, 1964

Our inheritance was left to us by no testament.

—René Char, Feuillets d’Hypnos, 1946

A few years ago, we, the Organ of the Autonomous Sciences, started a collective project that documented, mapped, and reflected upon a hostile takeover of the Situationist International’s methodologies by a group from the Danish ultraright scene. Our research was prompted by the spectacular 2019 parliamentary campaign run by the political party Hard Line (Stram Kurs) and their lawyer figurehead, Rasmus Paludan. Their use of daily “happenings” (usurping a central postwar avant-garde strategy), featuring various “props” such as toy guns as well as public urination and Koran burnings, managed to seize the public’s attention and cause a bombastic media spectacle.1

We are acutely aware that this text will leave the impression of having transgressed a taboo. The prevalent stance among Nordic intellectuals and commentators is that these “fascistoid” provocateurs should be silenced (deplatformed) to death. But increasingly, this strategy only seems plausible if one also ignores the very form and forum of today’s so-called “politics”: the pseudo–public sphere of social media.

Notwithstanding warnings of engaging with these neofascist provocateurs, we have increasingly begun to see the boundaries of this taboo as an integral part of spectacular fascism’s very ability to thrive. Public critiques of far-right phenomena often have appalling consequences. We have carefully considered whether the publication of our research could attract the uncomfortable attention of Paludan, who has a history of harassing and stalking his critics. While we share the commentators’ desire to undermine the far right’s violent operations and directly confront the ugliest swing of the “death spiral” of racist politics in the Nordic welfare states, we also need to problematize how proscription has become a guiding structure underpinning the plethora of bullshit that constitutes a global mainstreaming of far-right movements. This paradoxically both erodes and prolongs the fantasy of a liberal public sphere. In short, although we have sincerely wished that our research would eternally collect dust in the archive, we can no longer justify hiding it from public view. Lately, too many bad things have occurred.

What is Happening?

In April and May 2022, a series of strange and highly disturbing events were common front-page news in Scandinavia. For one, a video live-streamed on the Facebook page of the far-right group Patriots Go Live (Patrioterne går live) showed the anti-trans artist Ibi-Pippi vandalizing Asger Jorn’s iconic artwork Den foruroligende ælling (The Disquieting Duckling, 1959).2 This famous piece, displayed at Museum Jorn in the provincial Danish town of Silkeborg, is an example of Jorn’s “modification” technique, in which he would buy paintings at flea markets and paint over parts of them.

In this “happening”—which the artist called a “double modification”—Ibi-Pippi glued a self-portrait onto Jorn’s painting, then signed the painting in marker. Allegedly, Ibi-Pippi’s ambition was to question the notion of authorship. Reports say that the artwork was irreparably damaged by the action.

The disturbing thing about this “happening” is the eerie convergence between goofy right-wing artists and documenters and their avant-garde icon, Jorn.3 This impression was only bolstered by the identification of one of the other persons in the video as the notorious “penis artist” Uwe Max Jensen, who has earned a name for himself by urinating in an Olafur Eliason installation.4 In 2019 Jensen entered the political scene as the first candidate for Hard Line. Jensen, Ibi-Pippi, and others are often grouped under the nebulous “provo art” banner, which, unlike the anarchist Provo movement of the 1960s whose actions mainly provoked responses from Dutch authorities and the petite bourgeoisie, encompasses right-wing provocations that target immigrant, minority civilians in Scandinavia.5

Contemporaneously, Paludan made a spectacle when traveling through Sweden and burning copies of the Koran. Paludan, who founded Hard Line in 2017, acted as a defense lawyer for Uwe Max Jensen and others, while making a name for himself through YouTube videos on the channel “Frihedens Stemmer” (The Voices/Votes of Freedom).6 Then as now, his actions are designed to provoke violent clashes between frustrated minorities and the police to create a scapegoat. Staging demonstrations in over-policed and poor immigrant communities, Paludan provokes the public with actions like spitting on or burning the Koran. While Paludan is protected by the police, he capitalizes on the ensuing demonstrations against him in order to come off as the defender of freedom of expression while framing the ethnic minorities he harasses as unlawful and unbelonging “others.”

This specific fusion of neofascism and twentieth-century avant-garde aesthetic strategies is far from a unique case; it falls squarely into the “post-shame” nihilist irony of the global alt-right movement and their “culture wars.” There is, however, a local reference that ties this disturbing web together in this context: an almost forgotten movement in Scandinavian art, the “Nashists.” Our intention here is to show a continuity, however perverted, between that group and the objectionable media-warriors introduced above.

The first legal transgression of the Nashists was their co-painting of a public wall, 1962. Left to right: Jørgen Nash, Hardy Strid, Jens Jørgen Thorsen, and Dieter Kunzelmann.

The Emergence of Nashism

“Nashism” was the label for a group of Nordic artists who operated together from 1962 to 1976 and were excommunicated from the Situationist International. Its most prominent figures were Jørgen Nash, Jens Jørgen Thorsen, Hardy Strid, Ansgar Elda, Dieter Kunzelmann, and, to some ambiguous degree, Asger Jorn and Ambrosius Fjord. According to the First Situationists, the Nashists turned the “revolution of everyday life” into a source of popular entertainment. The Nashists propagated a “situationism” that legitimized expressionist gestures and staged “happenings” centered on artistic subjectivity—something a “critique” of the spectacle was supposed to have surpassed. If this is the more or less “correct” theoretical explanation for the excommunication, a more sectarian one is that the Nashists disrupted Debord’s desire for theoretical and organizational coherency, which led the unofficial leader to dispose of the Nordic rebels. Thus, as writer Howard Slater has put it, the exclusion of the Nashists could also be understood as a “defence against a threat to the idealized self-image.”7

The word “Nashism” first appeared in a 1962 issue of Internationale Situationniste. J. V. Martin defined it as a “term derived from the name of Nash, an artist who seems to have lived in Denmark in the twentieth century.”8 As Martin elegiacally framed it, Nash (Asger Jorn’s brother) was “a man primarily known for his attempt to betray the revolutionary movement and theory of that time.” Thus, Nash’s name was détourned by that movement and made into a generic term applicable to “all traitors in the revolutionary struggle against the dominant cultural and social conditions.” For our purposes, it is pertinent that Martin somewhat tautologically defines a Nashist in the broadest sense as “someone who in conduct or expression resurrects the intentions or essence of Nashism.”9

Acknowledging this historical context, our return to using the term “Nashism” could easily be misconstrued as a defense of the First Situationist International. To us, however, the structuring logic of Nashism seems not only easily detachable from Situationist sectarianism, but also stands on its own in a far stronger way today. While the twentieth-century Nashists could still frame themselves as a group of avant-gardist (pseudo-)revolutionaries pursuing a life outside capitalist exploitation by artistic means, the advent of neofascism has arguably raised the stakes. With this also comes the need for mobilizing the delegitimizing and condemnatory function inherent to the concept of Nashism, past and present.

The contemporary context that has once again given rise to Nashism has everything to do with the specificity of Danish culture and the mainstreaming of racist politics in twenty-first-century Scandinavia. The inhabitants of these cozy welfare states have decided that the Nashists’ transgressions are legal, even if morally repulsive. They have thus failed to take responsibility for this cultural and historical heritage. As Nashism via Paludan is becoming a new cultural export—to the entire world, but especially to our Swedish comrades who are now struggling against the newest recurrence of Nashism—we hope this essay can help, if not as an antidote, then at least as a clarification.

From these convergences, we propose a central thesis: Nashism is not only an undescribed movement in art history, but a continuous and neglected political reference. This is so because the current resurrection of Nashism has manifested and operated through a series of aesthetico-political strategies that are facilitated and empowered by the increasingly “compact spectacle” inherent to a stupefying attention economy.10 Rather than putting forth a conscientious and well-composed art-historical hypothesis, we want to tunnel through this antagonistic force by deploying a wider conceptual generator of multiple Nashisms. These are Nashism, neo-Nashism, and anti-Nashism.

As a vulgar appropriation and an “objective tendency” of the Situationist movement, the Nashists are finally returning from the gates of Hell in pure, concentrated form. The neo-Nashists not only follow the geographical path of the Nashists (who likewise moved from Denmark to Sweden in their break with the First Situationist International to found the municipality Drakabygget). They also explicitly develop and radicalize practices and codes that were already in circulation among the Nashists: from discriminatory and harassing transgressions to anti-trans rhetoric and libertarian conformism.11

The historical Nashists were of course never fascists, but rather saw themselves as anti-capitalist and anti-imperialist. However, as a cultural symptom that moves within the homogenous and contradictory storm of the society of the spectacle, Nashism has now revealed its true reactionary face—and like Minerva’s owl before dusk, some of this was already visible in the goofy and bellicose lineaments of its “founding fathers.” We understand the emerging forms of neofascist spectacle as an attempt at “racist re-enchantment,” in the words of Mikkel Bolt Rasmussen, which functions as the “thin varnish that just about covers the fractures of classless class society.”12 It thus becomes obvious that the rise of neo-Nashism serves as a peculiar, stinky example of a much broader, even global form of flesh-indulging fascism that circles around the historical avant-garde’s rotting corpse.

Nashism as a Tendency of the Situationist International

History has long been familiar with various forms of Situationist recuperation. In general, the Situationists’ afterlife has included some unsuitable heirs: first, late-capitalist spectacle’s recuperation of artistic critique and aesthetic emancipation, as outlined by Boltanski and Chiapello,13 and more recently, the spectacle of right-wing situationism that has revitalized the position of Nashism. In this context, Nashism could be seen as a conflation of the fifty years of “la droitisation du monde” and the “fifty years of recuperation of the Situationist International.”14

According to Martin’s original definition, the Nashists were essentially artists suffering from extreme self-adulation. Due to their desire to “be accepted in a society,” they did nothing but “expose the Situationist movement to mockery and laughter.”15 Feeding the society of the spectacle with obnoxious provocations, the Nashists were always keen on being swallowed by the spectacle itself. The “Nashist gangsters,” as they were later called in the eighth issue of Internationale Situationniste, were “much more sociable [than the Situationists], certainly, but much less intelligent.”16 Thus, steadily assured by the authenticity of the “original” Situationists, Debord points out how the Nashists engaged in a “systematic spreading of false information,”17 with help from “more-than-enthusiastic journalists employed by the Scandinavian press,”18 referencing Nash’s promiscuous “art dealing.” The personalized tone of Debord’s and Martin’s callouts underlines the logic of abjection that later became a definitive characteristic of the neo-Nashist movement.

In February 1962, a series of controversies culminated in the Situationist excommunication of the German Gruppe Spur, as well as the expulsion of Nash and the rest of the Scandinavians (besides J. V. Martin), who all ultimately supported Spur, which was facing legal proceedings in West Germany for distributing blasphemous and pornographic material in their new journal. This process laid the groundwork for the Nashists’ subsequent fetishization of legal transgression and freedom of speech, which is the most obvious connection to neo-Nashism.

Thus, from 1962 the Situationist International was divided into two easily identifiable yet opposing factions within a shared strategic field: a “French” First Situationist International, and a “Nordic” or “Scandinavian” Second Situationist International. However, the two groups explained the split very differently. Contrary to Martin, the Nashists believed that each faction of the movement had developed into a nationalism in Situationist disguise, which rendered the international impossible.19 They chose to affirm these identities in a manifesto, “The Struggle of the Situcratic Society,” published in Swedish and English in two new Situationist journals, Drakabygget and Situationist Times, with a visual design, terminology, and tone clearly based on Asger Jorn’s ethnicist-organicist analyses of the time20—he signed the manifesto with the pseudonym “Patrick O’Brien.”

As such, the Nashists reinterpreted the sectarian disagreements along cultural-organicist lines. They claimed that whereas the “Franco-Belgians” were “socio-centric” and regarded action as something preceding emotion, the “Nordic rebels” were “anthropocentric.”21 For the latter, the pre-reflective realm of emotion preceded both action and an analytical attitude towards social life. From the Nashists’ perspective, these cultural-ethnic traits determined two legitimate forms of Situationism. Specifically, the anarchist Nordic rebels would only allow the revolution of everyday life to arise “out of the situation itself” (their happenings, for example, which they theorized with the term “CO-RITUS”). They opposed the way that the bande dessinée of Marxist “Franco-Belgians” outlined a theoretical trajectory that was to be realized practically (through the methods of détournement, the dérive, etc.).22

As far as Nash was concerned, the Spur trial and his own artistic transgressions, by virtue of their specific Nordic attributes, were the most forceful means of combatting bourgeois society.23 In their manifesto, the Nashists nonetheless abstracted from the personalized-practical conflict between the two groups’ very masculinized attitudes to life, arguing that they could still be thought of as “complementary,” paraphrasing Jorn’s analysis of Niels Bohr’s quantum mechanics. This view proposes that the tribalism could be resolved eventually, but that each “situationism” was confined to “blossoming” within the milieu of its own ethnic Kulturkreis.24

In contrast, the First Situationist International analyzed the split through a political lens. They explained that any operation within the society of the spectacle is always potentially compromised, as it becomes an object of recuperation by the late-capitalist logic of attention and publicity. For Debord and the rest of the “French” originals, the Nashists were “cliché-mongers” and were merely a symptom. “It seems to us,” he wrote, “that Nashism is an expression of an objective tendency resulting from the Situationist International’s ambiguous and risky policy of consenting to act within culture while being against the entire present organization of this culture and even against all culture as a separate sphere.”25 In this light, today’s neo-Nashist “culture warriors” aptly put into practice the problem of art and artists in the spectacle society that the First Situationists had so far only theorized.

Notwithstanding the First Situationists’ sectarian motivations and censorious “idealized consciousness, based upon sovereignty of individualism,”26 which, as Howard Slater has stressed, abandoned any fruitful contradictions,27 their critique of Nashism was essentially on point, because soon enough, the original Nashists indeed became “star activists” or “experienced media workers.”28 They always managed to receive massive media exposure whether they acted in the streets of Copenhagen, the Danish Parliament, the Royal Danish Theater, the Venice Biennale, award shows, or in the context of the world press. They carried out the notorious “murder” of the bronze statue of The Little Mermaid, which according to Nash was to be read as a “media novel,” and added fuel to a global blasphemy debate with Thorsen’s film on Jesus’s sex life. In all these instances, the Nashists managed to posit themselves as “pioneers of the present,” as a “fun” way of reminding everybody that the North was still indebted to Christian guilt and shame. They called Scandinavia the “land of horniness,” and they steadily became household names as the provocateurs of the Nordic welfare model.29

Nashists, then and now, have always failed to construct genuinely free situations, as they depend on some authority within it—in concrete terms, the presence of journalists or police officers. Nashists, old and new, exploit a cunning method in which the police essentially sanction their provocations by standing guard against potentially violent reactions from their targets of harassment, whether minorities, journalists, or other artists. Consequently, Nashist happenings allow for neither chance nor free play, but rather affirm a need to be recognized and valued, as all Nashists seek to be honored members of society—in short, parrots (patriots).

Today, the Nashists should be lamented for fueling the public’s fascination with provocateurs. Their operative logic is already found in the etymological connotations of the Latin provocationem, which signifies a calling forth, a summoning, or a challenge. The actions of the Nashists should in other words be understood as challenges summoned by the society of the spectacle, and as such the Nashists are—in the Satanic sense—its minions. In this light, they can be understood as a “false friend” (or what Nash and later the Hard Line party counterrevolutionarily call the “Fifth Column”) in a general struggle against society and the prevailing conditions of culture.

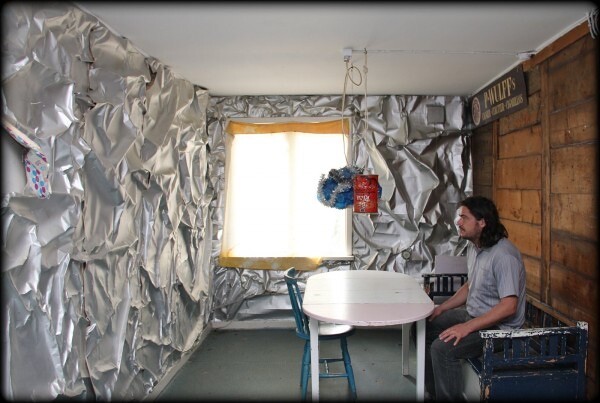

In 2012, Uwe Max Jensen visited the Tin Foil Hut in Floalt, Sweden, which was inhabited by Jens Jørgen Thorsen until his death in 2000. Image: Snaphanen.

Neo-Nashism as Right-Situationism

Today, a right-situationist wave has reawakened the dragon of stupidity, calling, in one egregious example, for the mass deportation of all Muslims. If we follow the First Situationist International’s critique of Nashism, we should likewise be able to conceive of neo-Nashism as a phenomenon that is called forth by the society of the spectacle, and that even in its most excessive acts cannot but respond to these terms.

Defining neo-Nashism as a fascist détournement of a gang of expelled Situationists from the 1960s can indeed attest to a far broader emergence of avant-garde strategies and trolling in neofascist subcultures. But what strikes us in the case of Paludan and his “Sancho Panza,”30 Uwe Max Jensen, is the crude and inverted radicalization with which they continue the program of the Nashists. In this way, they not only reveal the reactionary elements that were already at play, but also realize some of the actual effects that the Nashists could only dream of. As Debord rightfully stressed: “Brutally phrased: capital will never be lacking for Nashist enterprises.”31

The reasoning here is not simply that “provo” artists like Ibi-Pippi and Uwe Max Jensen, and by extension the Hard Line party, become Nashist simply by identifying with Nash, Thorsen, or Jorn, but that their actions have managed to bring about a neo-Nashism by operating through a series of obviously Nashist logics. It is impossible to decipher any boundary between the neo-Nashist aestheticization of the political, and the public and institutional embrace of the neo-Nashists. In fact, both sides of this productive reciprocity constitute one and the same racist spectacle.

This is all made possible by a culturally expanded sphere where art itself is a quintessential, “interdisciplinary” phenomena within the society of the spectacle: a fully compromised automata which seems to have colonized everyday life at a level far beyond Debord’s worst excesses of imagination. All the while, today’s transnational “art industry” ensures its continuing “absolute” commodification and semblance of autonomy.32 The contradictory disintegration of art within a far wider aestheticization of everyday life has rendered any project aspiring to sublate the realms of art and life completely obsolete.

If the First Situationist International really is the “last avant-garde,”33 as some critics have argued, then the Nashists might be seen as the “first” post-avant-garde. They manifest the exhaustion of any critical practice seeking to foster an Aufhebung or dépassement by refusing the officialized Abspaltung between art and life. These two realms have mutated uncannily by force of the society of the spectacle itself.

Today, this disintegration of art into the aestheticization of life, primarily facilitated by the emergence of social media, has opened up a very wide field of possibilities for the far right and other “fascists derivatives.”34 Rather than operating through traditional right-wing hotbeds such as veterans associations and military clubs, today’s far right uses 8chan and online gamer forums such as Discord to facilitate the spread of politically incorrect “content” to an increasingly hybrid and multilayered audience of atomized “spectators.”

The Paludan Show

Before earning his reputation as Denmark’s provocateur par excellence, Rasmus Paludan described himself as an artist. Echoing André Breton, and also Donald Trump, in 2016 he brought a realistic toy gun to a free-speech conference in the Danish Parliament featuring the Swedish far-right artist Lars Vilks. This event came just one year after another event in Denmark featuring Vilks as keynote speaker (called “Art, Blasphemy, and Freedom of Expression”) was subject to a so-called “Islamic terrorist” shooting with civilian casualties. Regarding the 2016 conference, Paludan insisted that he “wanted to try to illustrate with my artwork how the police act towards something that is completely harmless”—in other words: a white man with a (toy) gun.

Already in the early 2000s, Paludan proved to be quite creative at expanding the boundaries of the law as his personal fetish. He used the website kriminelle.dk to meticulously document cyclists’ unlawful behavior. Since then he has amassed a lengthy record of using his legal education to carry out serious harassment of ethnic and sexual minorities. However, the effect of these transgressive vendettas clearly pales in comparison with Paludan’s Koran-burning “demonstrations.” A former Danish prime minister described Paludan’s actions as “provocation for its own sake,” thus placing it beyond the official sphere of politics. Some political commentators have even wondered whether Paludan is performing one big stunt: “Is it just a game?”35

The truth value of such naive suggestions is continuously subtracted from Paludan’s “happenings,” which have steadily taken on a violent and dramatic character involving intense clashes between young minorities and the police.

These clashes include, on the one side, police bodies harmed by their effort to protect Paludan, which legitimizes the “vulnerable” state’s exclusive monopoly on violence (and public visibility). On the other side, there are the ethnic minorities who “allow themselves”—as people said then, and do now in Sweden—to be provoked by a rabid jackass who has already escaped the scene.

Paludan’s happenings deploy a strategy that we, acknowledging the right-situationist context, term racialized situology: their sole purpose is to construct situations with potentially violent responses from ethnic minorities.36 This actionist mobilization of a public audience, whipping them up into a violent “collective rite,” is at once a radicalization of the Nashists and their outright betrayal. Paludan’s subversive actions bolster the existing racialization that legitimizes “our” state-sanctioned racism. His happenings can be understood as involuntary parodies of avant-garde strategies, such as détournement or Verfremdung, as he—rather than exposing or inverting operative ideologies and social relations—is only able to affirm and intensify the usual racist imagery surrounding “the Muslim.”

A frequent site for extensions of Paludan’s happenings has been schools with large populations of ethnic and religious minorities—providing the ultimate (pseudo-)fulfilment of the avant-gardist reverence for “infantile disorders” and “primitivist” babbling. Teachers nationwide have reported schoolyard reenactments of Paludan’s stunts, including one where pupils divide themselves into “Muslims” and “Jews” who are put in a cage.37 This neo-Nashist appeal to children has been so strong that the Danish state TV channel DR produced a documentary titled Rasmus Paludan: Right Nationalism for Children, a program that clearly revealed who tricked whom. In the program, scenes depict children reconstruing Paludan’s idiotic actions via cunning gimmicks, causing visible frustration for the neo-Nashists.

A peculiar relation to infantilism clearly informs Paludan’s aesthetic and performance. In constructing his image, Paludan does not aspire to epic Landian heights, or even to the middlebrow ironic memes of the alt-right (whose meme characters, such as Pepe the Frog, are arguably reminiscent of the First Situationist International’s détournement of cartoons). Paludan’s lack of imagination also prevents him from pursuing the style of neo-totalitarian Monumental Art, as in Steve Bannon’s media empire. Pathetically, the aesthetics of Paludan & co. instead draw upon figures from Danish children’s television. In terms of voice, theatrics, and even worldview, Paludan has consistently constructed himself as the identical twin of the 2000s satirical character Dolph, a violent, racist, and fascist hippo.

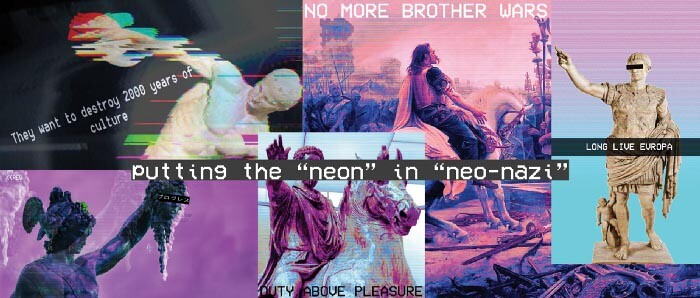

Fashwave art from various fora.

Most commentators agree that Paludan’s mode of expression, a kind of caricature of the Nashists’ beloved Homo ludens, is just too much. But through media hyperbole (“Is it just a game?”) and the effects it produces (“Why are non-Western foreigners so angry and violent?”), Paludan’s morally repulsive stunts become justified. His superficially antiestablishment tactics—paradoxically epitomized by police shields surrounding him at “happenings”—echo the Islamophobic aesthetic that we have become accustomed to since at least 9/11. Jonas Staal calls this aesthetic regime “expanded state realism.”38

The fascist gestures of Paludan and his ilk are undergirded by the “great replacement” master narrative, a conspiracy theory claiming that a secret global cabal is intent on replacing white, cis-gendered people with non-white people. This narrative is an enabling device for necropolitical racialization, stigmatization, and ultimately murder. In Paludan’s antics one can also hear the echoes of Nash and Thorsen’s outcry after forcing their way into the Swedish pavilion at the Venice Biennale in 1968 and transforming it into a “pavilion of revolt”: “This year they don’t exhibit art, but policemen.”39

Plan for the disruption of the Venice Biennale in 1968. Source: Situationisterne 1957–71: Drakabygget, Bauhaus Situationniste (Skånskå Konstmuseum, 1971).

Exit the Paludan Show

We need to underline that the emergence of Paludan and the other neo-Nashists is unthinkable without the acute mainstreaming of a far-right agenda in Denmark. It therefore might seem rather peculiar that as Paludan’s exuberant media exposure has grown, most commentators and politicians have increasingly treated him as the name-not-to-be-mentioned.

But the majority’s deviating behavior and ignorant views display that they know Paludan is their own shameless bastard, that they have fostered him, and they are thus also to blame for his “bad-mannered” behavior.40 The existing Islamophobia and racism in Denmark’s political culture allowed Paludan to shamelessly posture as the state’s leading comic actor.41

During Paludan’s rise to fame, a wide coalition of Danish parties agreed on the so-called “ghetto package”: a cluster of policies based on ethnic criteria (“foreigners” or descendants of foreigners from “non-Western” countries) and racial profiling implemented through temporary visitation and double-punishment zones, as well as forced expulsion from residences. The political background for this is explicitly formulated as the destabilizing and threatening factor of “non-Western” foreigners. The state’s racialized motivation likewise legitimized the establishment of new deportation centers in Sjælsmark and Kærshovedgaard, where rejected asylum seekers live under systematically restrained conditions worse than those of Danish prisons. These centers are placed in close earshot of the trauma-evoking noise of military camps.

Continuing on this endless road of patriotic bravery, the Social Democratic government is currently acting as the world’s xenophobic avant-garde with plans to install detention centers in Rwanda and prisons in Kosovo. And the current refugee crisis caused by the war in Ukraine has put discrimination in plain sight, as “non-Western” migrants and refugees continue to be treated very differently than white (Christian) Ukrainians.

Paludan’s disobedient happenings produce a more entertaining, dramatic, and disgusting image of the state’s authoritarian and xenophobic fight against “Others.” When Paludan “proves” that young Muslim men are criminals whose “psychological constitution” displays their inferior “stage of civilization,” as a Danish politician tweeted after a happening, it is easier to exclude “them” from fundamental democratic rights. This imaginary of the “inferior, uncivil Muslim” and the “civil, white Western Man” puts a fresh coat of paint on an old racist logic, as described by Ana Teixeira Pinto: “Racial animosity is always expressed in the language of principle.”42 Especially in the case of neo-Nashists, this logic manifests in a contradictory form.

In this sense, the neo-Nashists can be conceived as a strange reversal of the fascist “aestheticization of political life” famously discussed by Walter Benjamin. Rather than using radio or cinema to project a homogenous, ornamentalized ethno-nationalist image that gives expression to and organizes the masses, Paludan uses digital platforms to coproduce the image of an “us” (white Western) and a “them” (Muslims) that disorganizes and fragments the masses. These provocations draw upon fascist tropes of aestheticizing violence that have been known since the futurists and the “avant-garde fascism” of the interwar years, where politics was boiled down to the mythmaking of heroes and enemies.43 Evoking a painting from 2016 by Uwe Max Jensen displaying Paludan in a heroic act of public shooting, Paludan himself once stressed in a demonstration (ed. trigger warning): “Our streets and alleys will be turned into rivers of blood, and the blood of the alien enemies will end up in the sewer where the aliens belong.”

Despite being appalled by Paludan’s Nashist methods, liberal and even left newspapers create a more moderate—but often no less racist—version of the aesthetic effects of the neo-Nashist spectacle. Provocations—in this case with “Muslims” as the objects of provocation, and “Danes” as its subjects—can be eerily comforting. This stems from the fact that Paludan merely produces and stimulates images that are already in circulation. He affirms the “truth” through a dramatic image of what is already known.

In contrast to the “uncivil” behavior of non-Westerners, the Danes display their “civility” by publicly accepting and defending Paludan’s “right” to free speech—and by logical necessity condemning ethnic minorities for their violent behavior in response to his taunting provocations. Consequently, few have questioned the racist and repressive context for this “violent behavior,” nor the fact that the “pain of others” is turned into the “measure of our freedom.”44 The discussion is stunted at the level of principle: “Freedom of speech is not for sale,” as the original Nashists exclaimed at their mass demonstration on the main street of Strøget, Copenhagen in 1965.

To a certain extent, the neo-Nashists have simply continued the Nashist struggle for freedom of speech, as if nothing had happened since the 1960s. “Artistic freedom of speech has no moral limits” was another Nashist slogan.45 As artistic speech, this liberal principle is extended from discourse to action, which entails a broader palette of expressions. Thus, the neo-Nashists can exploit a principle that first came into being with their forebears: a “fundamentalist” notion of freedom of speech that authorizes the amoral expression of privileged bodies. However, whereas the Nashists largely focused on artistic freedom of speech as embedded in the struggle to subvert bourgeois, nationalist, and conformist morality, the neo-Nashists employ free-speech subversion either as a pure medium, or as a kind of reactionary transgression that sanctions and further racializes existing social relations and their anti-queer and white-supremacist morality.

While the Nashists struggled against the state—despite being fully dependent on its system of support—the neo-Nashists are paradoxically struggling against and for the state, like sad “heroes” that fortify the Danish state at day and break its laws by night. This is true of most examples of neofascist tendencies that mine the historical avant-garde. So, while the pseudo-praxis of Nashism ultimately only bolstered the pseudo-reality against which it was supposed to fight, this same structuring logic now seems to assist neo-Nashism in coproducing the state-sanctioned racism that is so intimately desired by a reality-hungry public sphere. For the Nashists, this immanent contradiction was what made their endeavor into a spectacle—that is, made them Nashist—while the neo-Nashists can more easily thrive on this contradiction.46

“Ban the Nash!”

Throughout this text, we have tried to hyper-thesize the First Situationists’ more or less on-point takedown of the Nashists as a template for dealing with contemporary fascisms. Naturally, we don’t believe that a short genealogy like this will be able to do this by itself. Today, critique can only hope to raise an eyebrow.

Therefore, it is obvious for us that we must synthesize the situation in relation to a general order of the spectacle. In doing this, we must avoid any embarrassing intellectual-moral explanations, or even worse, any attempt to reclaim a neo-Debordian Situationism that would amount to telling an esoteric Hegelian joke at the dinner table during the honeymoon days of the Vienna circle. We prefer to have our cake and eat it too.

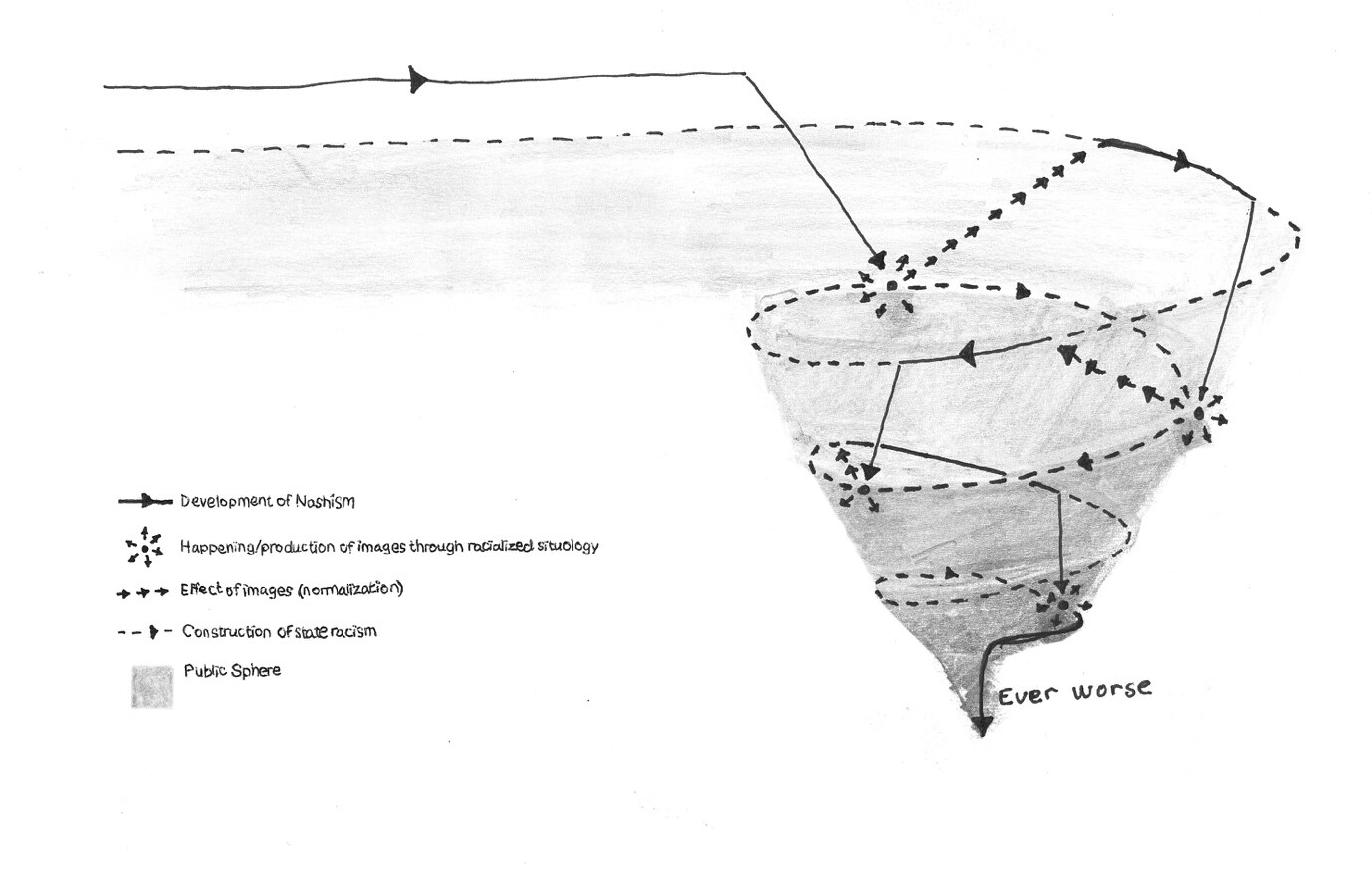

Diagram on the eternal resurrections of Nashism. Courtesy of Organ of the Autonomous Sciences.

Fortunately, we can address the neo-Nashists as nothing more than the idiotic friends of our true enemies by allegorizing the First Situationists’ lamentations one more time. In a letter to J. V. Martin dated May 8, 1963, Guy Debord outlined a new position: anti-Nashism. “We are quite in agreement on the fact that you must try to take artistic and theoretical control of the new anti-Nashist and anti-nuclear gallery (Ban the Nash),” he wrote.47 In French, the last phrase is “A bas le Nash,” an allusion to the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND)’s iconic 1953 slogan “Ban the Bomb.”

Rather than continuing a personal polemic with the Nashists, Debord’s new concept of anti-Nashism addresses the colossal scale of the problem through multiple references to a global network of revolutionaries (CND and the Spies for Peace group, amongst others). For our analysis, this essentially places the problem of the neo-Nashists on par with the way the atomic bomb and its associated security measurements should be regarded: a pretext for the passivation and militarized domination of the society of the spectacle.

So far we have pinpointed how neo-Nashism operates as a molecular nuclear weapon within the territory of Danish state racism. The anti-neo-Nashist question is more difficult to answer: How can we ensure the banning of this bomb without resorting to the liberal phantasmagorias of isolated and pseudo-public “critique” or “dialogue” that so blindly lets itself whirl into the death spiral of Nashism?

In his brief note on anti-Nashism, Debord references a gallery exhibition that took place at Tom Lindhardt’s Galerie Exi in Odense, Denmark. Here, the First Situationists arranged for the exhibition “destruction of rSg-6” to take place as a response to the Nashists’ spectacular betrayal. The reason for the Situationist exhibition in Galerie Exi was indeed to solve the difficult conundrum that Nashism originally evoked: namely—as Mikkel Bolt Rasmussen has also articulated—how to act within culture while being against all culture as such.48 Of course, this mission had to fail, as the gallerist Lindhardt became publicly outraged about “hosting a shooting match” when he was “promised an art exhibition,” which ultimately forced the Situationists to retreat from the scene.

As a reaction to Paludan, a collective of jazz musicians began assembling at the locations of his racist happenings, with the aim of producing noise against the fascist noise of the neo-Nashists. Encouraging everyone to bring an instrument, this quickly evolved into a remarkable popular and anti-fascist form of protest. Photograph from the Facebook page “Free Jazz Mod Paludan” (Free Jazz Against Paludan).

Here we must point out a regulative idea, which was already inscribed in the exhibitory logic in Odense, and which any emphatic anti-neo-Nashism should rely upon. If we really want to disarm this particular atom bomb—ban the Nash—then we cannot narrow our focus to the bomb itself, which in the end only functions as a personification of the atomic reactor and the whole toxic infrastructure that gave birth to the bomb in the first place—that is, the too-late society of spectacular fascism that saps our sense of living. We can only combat Nashism by pursuing a strategic terrain that renders its conditions inoperative.

We must continuously invent routes for egress, desertion, and destitution, and elicit a mass dropout from the unofficial fascist tutelage imposed by our own shameless bastards. To navigate in the striated field of a shrinking universe, where the spectacle can always recur in any guise and place, we must seek out the limits—less by expanding our bodies than by securing ground and forging new organisms. We must bring forward a resistance by further bolstering the undercommon worlds that are poisonous to the neo-Nashists’ soil. Any victory will emerge from our efforts to stand outside the worst of it all. And in this sense—as Michèle Bernstein’s efforts demonstrated in the Odense exhibition—we have already won.49

Just weeks before the election, Hard Line managed to receive triple the media exposure compared to the two prime minister candidates. Although the party’s alleged mission to enter parliament failed (by only 0.2 percent of the vote), Hard Line clearly won in the eyes of the generalized attention economy. The party garnered millions of YouTube and Snapchat views—the latter among children and teens especially—and graced the headlines of the largest Danish newspapers, in which Paludan became the third-most-mentioned politician during the campaign.

To promote an anti-trans agenda, Ibi-Pippi has exploited a law concerning legal gender change to conduct various purposefully triggering actions, such as attempting to access a female changing room and a swimming class for Muslim women. Previously, Ibi-Pippi also walked in a “hetero pride” parade, penetrated a Putin blow-up doll, and carried out a public performance that allegedly involved blending and drinking a fetus.

While most critics believed that Ibi-Pippi’s vandalism was an act of spontaneous idiocy, a quick dive into Facebook reveals that this idea of making an “homage” to The Disquieting Duckling had actually been brewing for five years, as depicted in a painting including pedophilic imagery →. Ibi-Pippi also claimed to be in spiritual contact with Jorn beforehand → (watch 03:00). This does not take away from the stupidity of the action as much as it underlines the persistent veneration that a new generation of far-right artists seems to hold for Jorn. This problematizes the analyses that have framed the incident at Museum Jorn as some sort of “right-extremist” attack on a “left-wing artwork.” See, for example, Lukas Slothuus, “Why Is the Danish Far Right Vandalizing Left-Wing Artwork?” Jacobin, April 5, 2022 →.

In 2016 Jensen attempted a similar performance in the Kunsten art museum in northern Denmark but ended up violently assaulting two employees. Jensen was sentenced for the assault. More recently, Jensen gave the opening performance for a far-right exhibition in Warsaw, where he yelled the n-word, waved the Confederate flag, and reenacted the murder of George Floyd in blackface.

For another example of the legacies of fascist-leaning “provo art,” see Sven Lütticken, “Who Makes the Nazis?” e-flux journal no. 76 (October 2016) →. —Eds.

In a Danish political context, an obvious predecessor for this “Faustian pact” between a provo artist and a far-right lawyer can be identified from 1970–73. Back then, the Situationist provo Jens Jørgen Thorsen hired the charismatic libertarian provo Mogens Glistrup as his defense lawyer. In 1973, Glistrup entered the Danish parliament with the populist-libertarian Fremskridtspartiet, a party acclaimed and affronted for its heroization of tax cheaters and anti-Muslim politics. Thorsen’s connection to the far-right was further bolstered in the late 1970s and ’80s when he toured around Denmark with a central member of Fremskridtspartiet, Kristen Poulsgaard, in the aftermath of the anti-intellectual movement “Rindalism.”

For an in-depth account of the exclusion and subsequent emergence of the Scandinavian Situationists, see Howard Slater, “Divided We Stand: An Outline of Scandinavian Situationism,” Infopool, no. 4, 2001 →. Notwithstanding the virtues of Slater’s text, it suffers from a complete lack of attention to the Nashists’ more diabolical side. It shares this with later discussions by Jakob Jakobsen, Mikkel Bolt Rasmussen, and others.

J. V. Martin, “Définition,” Internationale Situationniste, no. 8 (January 1963): 26; appeared in Danish in Situationistisk Revolution, no. 3 (1970): 44.

Martin, “Définition” (emphasis ours). This conceptual trajectory seems all the more ironic given the anti-fascist origin of its very name. Born as Axel Jørgensen, “Jørgen Nash” was—according to biographer Lars Morell—originally a cover name taken up by a young, up-and-coming poet who was sent to Nazi Germany by the Danish resistance movement as a specialist worker in aviation. In 1941, “Nash” was caught by the Gestapo and detained in Berlin for two months. As such, Nashism is already a cruel détournement of an explicitly anti-Nazi pseudonym.

With the notion of “compact spectacle,” we borrow the epistemological standpoint of Debordian diagnostics. For Debord, the society of the spectacle is conceived as a fetus whose evolutionary-cumulative stages morph from the bureaucracies of totalitarian states (concentrated spectacle) to the great commodity boom of the postwar Keynesian compromise (diffuse spectacle) and ultimately to the synthesis of a neoliberal, biopolitical totality (integrated spectacle). If, in other words, we think of Debord as a driver on the catastrophic highway of Western modernity, “our” contemporary moment seems to induce the feeling of living amid a universal traffic jam caused by a crash between a few unmanned monster trucks and a gang of street vendors.

In his memoir The Mermaid Killer Crosses His Tracks (Havfruemorderen krydser sine spor), Jørgen Nash publicly mocked and scorned the gender transition of his ex-spouse and former Situationist Peter Albert Lindell. Describing a meeting between the former couple in Malmö Kunsthal, Nash stresses how he first fell into a state of shock, then a fit of laughter, and lastly a furious state of mind where he desired “to murder this crazy person.” Paradoxically, Nash chooses to impose clear limits on the life-form of his former partner, while at the same time celebrating the “limitlessness” of his own artistic and sexual freedom, which in the memoir is visible when Nash brags about having sex with minors and their mothers at his and Lindell’s riding school.

Mikkel Bolt Rasmussen, Late Capitalist Fascism (Polity Press, 2021), 132.

Luc Boltanski and Eve Chiapello, The New Spirit of Capitalism, trans. Gregory Elliott (Verso, 2005).

François Cusset, La droitisation du monde (Textuel, 2016); McKenzie Wark, 50 Years of Recuperation of the Situationist International (Princeton Architectural Press, 2008).

J. V. Martin, “Antipolitical Activity,” Situationistisk Revolution, no. 1 (1962): 26, 27. This text is translated into English (which we are using here) in Cosmonauts of the Future, ed. Mikkel Bolt Rasmussen and Jakob Jakobsen (Neblua and Autonomedia, 2015).

“L’operation contre-situationniste dans divers pays” (author anonymous), Internationale Situationniste, no. 8 (1963): 24. Translation borrowed from →. Translator Kenn Knapp suggests that this text was written by Guy Debord.

“L’operation contre-situationniste,” 26.

Martin, “Antipolitical Activity,” 99–100.

Paraphrasing a later text by Thorsen, this strange Nashist nationalism or cultural organicism was of course “anti-nationalist,” but with its libertarian individualism, it was mostly “anti-internationalist” in effect. See Jens Jørgen Thorsen, “Draft Manifesto of Antinational Situationism,” in Cosmonauts of the Future.

For Asger Jorn’s writings on the ethnic and organic characteristics of Scandinavia, see The Natural Order (1962) and Things & Polis (1964).

“Kampen om det situkratiske samhället: Et situationistiskt manifest,” Drakabygget – Tidsskrift för konst mot atombomber, påvar och politiker, no. 2–3 (1962): 15.

“The Struggle of the Situcratic Society: A Situationist Manifesto,” in Cosmonauts of the Future, 92. The Swedish and English versions of the manifesto contain small differences.

Jørgen Nash, “Konstens Frihet,” Drakabygget, no. 2–3 (1962).

This term used by Nash and Jorn might very well derive from the writings of the racist anthropologist Leo Frobenius, who also figures in Jorn’s texts.

“L’operation contre-situationniste,” 24.

Lars Morell, Poesien breder sig: Jørgen Nash, Drakabygget & situationisterne (Det kongelige bibliotek, 1981), 79.

Slater, “Divided We Stand.”

Morell, Poesien breder sig, 85. Posing as journalists was a strategic camouflage often employed by Nashists to enter inaccessible sites, and was described by Nash as a method of the Fifth Column. This is also a general trick employed by Uwe Max Jensen and was used to get Ibi-Pippi into Museum Jorn in 2022.

Jens Jørgen Thorsen, Wilhelm Freddie: Brændende blade (Internationalt Forlag, 1982), unpaginated.

Madame Nielsen, “Er Kristian von Hornsleth og dermed ’provokunsten’ virkelig død – eller bare ligegyldig?” Dagbladet Information, July 27, 2020 →.

“L’operation contre-situationniste,” 26. Emphasis in original.

For more on this “interdisciplinary” dimension within the context of propaganda, see Jonas Staal, Propaganda Art in the 21st Century (MIT Press, 2019). On the notion of the “art industry” as complementary to the “culture industry,” see Peter Osborne, Anywhere or Not at All: Philosophy of Contemporary Art (Verso, 2013), 162–68. With the word “absolute,” we allude to Adorno’s briefly stressed idea of art as an “absolute commodity” in order to encompass the peculiar economic exceptionality of art. See Theodor W. Adorno, Aesthetic Theory, trans. by Robert Hullot-Kentor (Continuum 1997), 21; and Stewart Martin, “The Absolute Artwork Meets the Absolute Commodity,” Radical Philosophy, no. 146 (November–December 2007).

Mikkel Bolt Rasmussen, Den sidste avantgarde: Situationistisk Internationale hinsides kunst og cirkler (Politisk Revy, 2004).

Hito Steyerl, Duty Free Art (Verso, 2017), 181.

See Søren Schauser, “Tænk om Rasmus Paludan var et stunt,” Berlingske Tidende, May 6, 2019 →.

As literary scholar Jørn Erslev Andersen has recently argued, Asger Jorn explored the notions of situology and triolectics to conceptualize an aesthetic-epistemic process that never synthesizes (as in dialectical movement), but rather manifests as an open situation, in what he termed a “transformative morphology of the unique.” In contrast, the situology at play in neo-Nashist happenings is neither dialectical nor triolectical, but rather seems to follow a monolectic logic of subjugation and repulsion. This is a closed situation that is given in advance, an “isomorphology of the same.” For an in-depth account of Jorn’s situology, see Jørn Erslev Andersen, At sætte i situation: Asger Jorns triolektik & situlogi (Antipyrine, 2017).

For a report on Paludan’s appeal to schoolchildren, see Peter Thomsen, “Stram Kurs-leder er blevet et Youtube-fænomen blandt skolebørn,” Berlingske Tidende, September 19, 2018 →. Ultimately, Paludan’s political project in Denmark collapsed when he got caught in an online “sex chat” with underage boys on Discord. This marked the complete transition of neo-Nashism from an intriguing “child monster” to full-on demonolatry—a point of transgression that Paludan only affirmed when, three days after the revelations, he sought to stifle what he called “homophobic rumors” by announcing his marriage to a younger woman.

Staal, Propaganda Art in the 21st Century, 77.

This is reported in a catalogue text from the exhibition “Situationister 1957–71 Drakabygget,” held at the Skånska Konstmuseum in Lund, Sweden in 1971. The text can be read online at →.

In 2019, just a few months after the election, a survey showed that 28 percent of Danes agreed “strongly” or “somewhat” with this xenophobic statement continually expressed by Paludan: “Muslim immigrants should be sent out of the country.” See Jens Reiermann and Torben K. Andersen, “Hver fjerde dansker: Muslimer skal ud af Danmark,” Mandag Morgen, October 21, 2019 →.

See Mikkel Bolt Rasmussen, “On the Turn Towards Liberal State Racism in Denmark,” e-flux journal, no. 22 (January 2011) →.

Ana Teixera Pinto, “Illiberal Arts,” Paletten, November 4, 2020 →.

See Mark Antliff, Avant-Garde Fascism: The Mobilization of Myth, Art, and Culture in France, 1909–39 (Duke University Press, 2007).

Lene Myong og Michael Nebeling, “Racismens vold er modstandens kontekst,” Eftertrykket (originally published at peculiar.dk), April 22 2019 →; Pinto, “Iliberal Arts.”

Tellingly, the famous Swedish “hate speech” artist Dan Park made a symbol-laden election poster for Hard Line’s Uwe Max Jensen that included the phrase “freedom of art.”

On the relation between actionism and contemporary fascism, see Lütticken, “Who Makes the Nazis?”; and Lütticken, “The Power of the False,” Texte zur Kunst, no. 105 (March 2017) →.

Quoted in Mikkel Bolt Rasmussen, “To Act in Culture While Being Against All Culture: The Situationists and The ‘Destruction of the RSG-6,’” in Expect Anything, Fear Nothing, ed. M. B. Rasmussen and Jakob Jakobsen (Nebula and Autonomedia, 2011), 112.

Rasmussen, “To Act In Culture,” 96.

At Galerie Exi, Michèle Bernstein installed a series of model tableaux with titles from revolutionary defeats renamed as victories, e.g., Victoire de la Commune de Paris, Victoire des Républicains Espagnols, and Victoire de la Grande Jacquerie.