Portrait of Jonas Mekas with Bolex. Photo: Boris Lehman.

Jonas Mekas memorial in Semeniškiai village in Lithuania, 2018. License: CC BY-SA 4.0.

Anthology Film Archives, cofounded by Jonas Mekas, in the East Village of Manhattan. Originally a courthouse, the building was sold to Anthology Film Archives in 1979 and was converted for their use by architects Raimund Abraham and Kevin Bone. Courtesy of Anthology Film Archives. License: CC BY-SA 4.0.

Anthology Film Archives’ vault with Jonas Mekas. Courtesy of Anthology Film Archives.

Portrait of Jonas Mekas with Bolex. Photo: Boris Lehman.

Many in the art world are observing the centennial of the Lithuanian-born poet and filmmaker Jonas Mekas (1922–2019), a founder and icon of avant-garde cinema. Cultural programs, exhibits, and conferences are marking the occasion. But not everyone is celebrating. In two recent reviews, historian Michael Casper has made allegations that appear to tarnish Mekas’s legacy. The first, published in the New York Review of Books (NYRB), took aim at the poet-filmmaker’s diary/memoir I Had Nowhere To Go.1 The second attack appeared in Jewish Currents as a review of “The Camera Was Always Running,” an exhibition of Mekas’s work in New York that concluded in June 2022.2

The two articles focus on Mekas’s wartime activities and his refugee experience. Casper claims that Mekas was evasive and dishonest about his wartime activities, and then proceeds to paint him, an eighteen-year-old when the Wehrmacht invaded Lithuania in 1941, as a Nazi sympathizer, if not outright collaborator. One would assume that such a dark indictment of an American cultural icon would require clear and convincing evidence, if not proof beyond a reasonable doubt, but the case presented disappoints. The review format of the articles allowed Casper to present judgements without the burden of buttressing his allegations with relevant sources and requisite detail. The resulting narrative turns Jonas Mekas’s life as a young man into something that it was not. Casper also employed the filmmaker’s ostensibly dark past as a vehicle to pronounce on broader issues of collaboration, nationalism, and revisionism. He tells us to “move beyond the superficial,” echoing Princeton historian Nell Irvin Painter’s recent lament on the “national hunger for simplifying history.”3 But Casper’s account of Mekas’s life fails in this regard. The reader gains no real understanding of a young poet’s life under conditions of war, foreign occupation, and exile. We learn little of the harsh realities of Lithuanians caught between the grindstones of two criminal regimes and find no useful description of the conditions they endured, or the reasons they fled their country.

More often than not, all that we find are suggestive images and associations that seek to denigrate Mekas’s person. As an example, in the Jewish Currents article Casper contrasts two evocative events of the same day (June 16, 2019): the unveiling of a memorial in Biržai, Lithuania to the town’s murdered Jews, a commemoration witnessed by thousands, including Casper; and Mekas’s burial, described as a “secret ceremony” in nearby Semeniškiai, his birthplace. Casper pits these unrelated gatherings against one another: a proud march for historical truth vs. a shameful clandestine gathering—a dramatic juxtaposition to be sure. But why is Mekas’s burial “secret” rather than “private,” a common-enough practice? Professional film crews recorded the Reformed Protestant burial service attended by dozens of the poet’s relatives and friends, some of whom spoke with reporters. Videos of the funeral appeared on Lithuanian national and local media outlets and are easily found on YouTube. So how “secret” was this ceremony? Words matter, as do images. The photo beneath the headline of the Jewish Currents article shows Mekas’s “temporary foreign passport” issued by the Reich authorities, complete with swastika. Casper intends for this to look compromising, but the picture only proves that Mekas received the same ID as many thousands of other non-German refugees, allowing them passage through checkpoints and access to food rations. I still have my parents’ certificates among the family papers.

Two disclaimers on my part as I go on to consider the shallow allegations made against the late artist. I have no expertise in American avant-garde culture which, in any case, has no relevance to Mekas’s wartime past or the two articles mentioned above. The second caveat is personal. In the 2018 NYRB review, Casper cited me as a “Lithuanian-American historian.” True, I am of the cohort who arrived in America from the displaced persons (DP) camps as small children and, as adults, chose to restore, sometimes as dual citizens, close ties to the land our parents had fled. Whether this background enhances or undermines what I write here is for the reader to decide.

Finally, a clarifying stipulation. My research has centered on the decade that followed the first Soviet occupation of Lithuania in 1940, the deadliest period in the country’s history. Casper brings up revisionism, a burdened idea often associated with Holocaust denial. This issue requires serious consideration, but we should be clear about what is not in dispute. The genocide of the Jews was the greatest instance of mass murder in Lithuanian history, incomparable in scope, and one in which a part of the ethnic Lithuanian populace participated. The ultimate horror has a timetable. Before the murder of the Jews of the Biržai region (Mekas’s birthplace) in the first week of August 1941, an estimated 90 percent of Lithuania’s Jews were still alive. Less than three months later, almost three-fourths were dead. Following this unprecedented bloodbath, about forty thousand Jews labored in the starving urban ghettos (Vilnius, Kaunas, and Šiauliai), a pause which amounted to but a temporary reprieve—essentially existence on death row. Less than ten percent of Lithuanian Jews ultimately survived: some by fleeing the country eastward ahead of the Nazis; others by hiding among rescuers; some simply by sheer chance. According to official Lithuanian estimates, between 190,000 and 206,000 Lithuanian Jews died in the Holocaust.

This history is well known to mainstream scholars everywhere and is accepted as fact by reasonable people in Lithuania.

Soviets, Germans, and Mekas: A Teenager in War

The most damning of Casper’s assertions is that the aspiring poet had been “deeply involved in political activism that led him to support the Nazi occupation of Lithuania during the critical period when the Jews were killed.”4 To understand whether this charge has merit requires a grasp of what transpired in Lithuania before and during the Nazi invasion and subsequent occupation (1941–44), and a closer look at Mekas’s activities during this fateful period. The aspiring poet’s boyhood and adolescence passed under the rule of Antanas Smetona (1926–40), whose authoritarian regime permitted a degree of artistic freedom, financed the education of national minorities (including Jewish public schools), and contributed to the salaries of priests and rabbis. This all ended with the Soviet occupation of Lithuania in the summer of 1940. The occupiers found followers among those disaffected by Smetona’s political repression, while even the majority of the country’s Jews opposed to Communism could see the Soviet army as a protector against the Nazi threat next door. But most Lithuanians, ashamed of the government’s collapse in the face of the Kremlin’s threats, placed their hopes in a breakdown of the Soviet-Nazi partnership established in August 1939.5 The Soviet occupation produced a toxic brew of resentments, one of which was the perception of Jews as traitors. Fantasies of Judeo-Bolshevism gained currency. Not surprisingly, the geopolitical orientations of the country’s national/ethnic communities (and not only those between ethnic Lithuanian and Jews) diverged sharply and tragically. Jewish memoirs have described the volatile atmosphere as rife with social tensions, on the verge of explosion.

The Journey of a Jew with Stalin, caricature. Example of underground anti-Semitic propaganda from 1940s Lithuania. Source: Lithuanian Special Archive, Vilnius →.

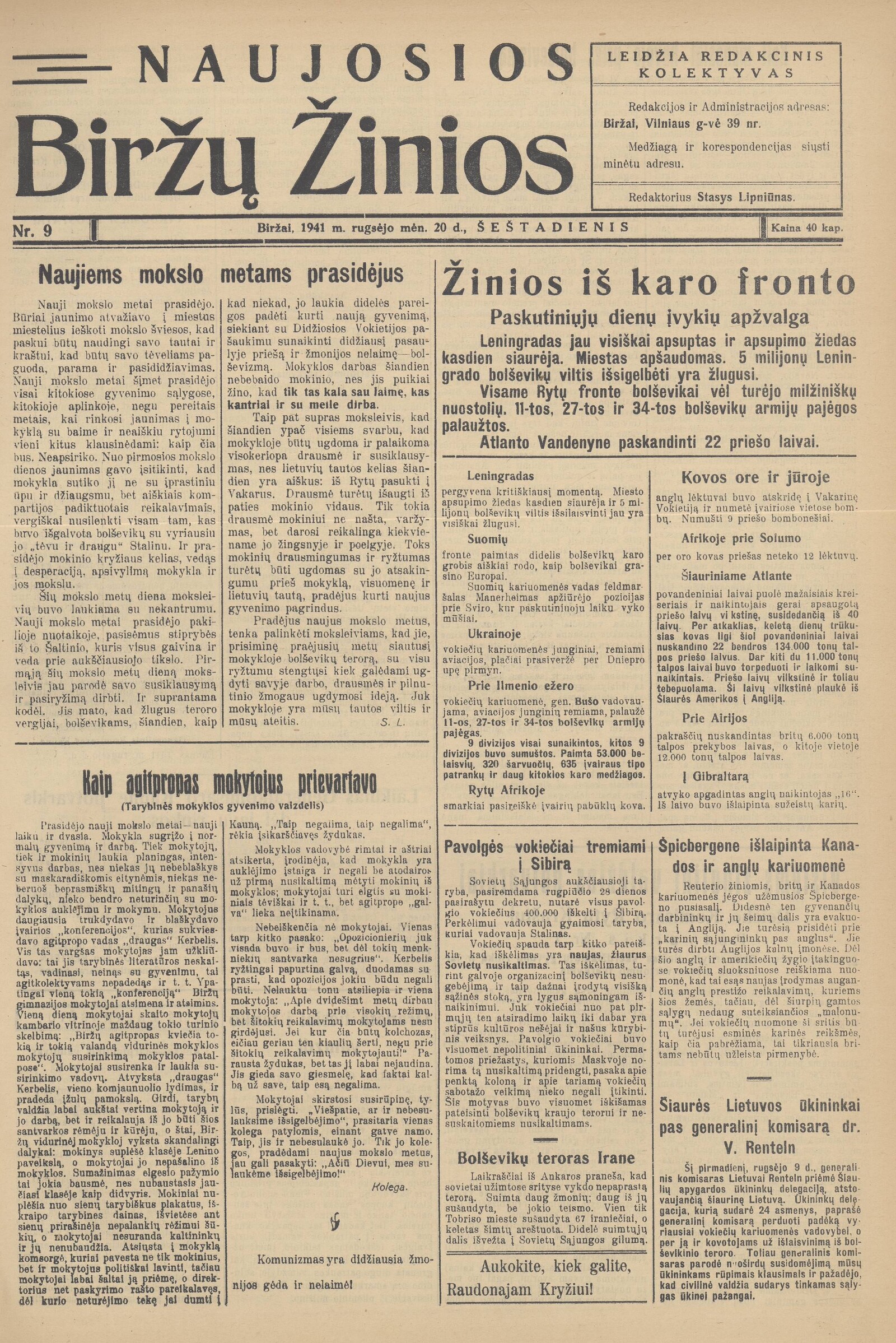

Where was the young Mekas in all of this? Casper claims that the poet was a member of an underground movement that “supported the 1941 Nazi invasion of Soviet Lithuania.” On closer inspection we see that Mekas joined a gaggle of teenage students in posting anti-Soviet leaflets (“Down with Stalin”) in late November 1940, which police tore down within hours. These bumbling adventures were described in the August to September 1941 issues of the Biržai weekly Naujosios Biržų žinios (The New Biržai News, henceforth NBž), published as excerpts from the diaries of “the Six,” the name the youngsters chose for themselves. My mother taught literature at a secondary school in Kaunas and recalled that some of her students “raised a ruckus” when asked to read Pushkin as part of the new, Russified curriculum. To call such outbursts an underground movement seems strange. (The anti-Semitic Lithuanian Activist Front [LAF], founded in November 1940 in Berlin, did create a network of followers within the country, but it did not appear until months later. Most of these underground cells were broken up by Soviet security before the Nazi invasion.)

The predicted and feared anti-Soviet explosion erupted when the Wehrmacht invaded the USSR on June 22, 1941. Much of the Lithuanian populace welcomed the Germans, the euphoria recounted in numerous memoirs. For many Lithuanians, the long-awaited war came as a relief, an end to Soviet repression, which had culminated in mass deportations (June 14–17, 1941) only days before the German attack. At the invasion’s onset, thousands of mostly young rebels rose up against the retreating Soviets. This June Uprising, as it is usually described in Lithuania, was brief (less than a week) and largely spontaneous. The majority of the roughly twelve thousand soldiers of the Red Army’s Lithuanian-speaking corps mutinied or deserted en masse: under the circumstances, there was no point in dying for Stalin. Rogue fighters attacked civilians, mainly Jews and accused Communists. Anti-Jewish violence intensified with the arrival of the Germans. A sense of impunity encouraged criminal assaults, which the rebels themselves documented at the time. For their part, the NKVD, the Red Army, and Soviet activists massacred nearly a thousand civilians as they retreated.

The LAF leaders who had evaded the Soviet police emerged from the underground and proclaimed a short-lived (June 23–August 5, 1941) provisional government as an independent state in alliance with Germany. The media broadcasted effusive accolades to Hitler and the German forces in gratitude for the nation’s “liberation” and announced a willingness to join the “New Europe” in the struggle to crush Bolshevism. The LAF’s political ideology and alliances were to prove morally and politically ruinous, widely judged as shameful, except by its still active apologists. After the war, even former LAF leaders rather weakly admitted that the Front’s program contained “totalitarian tendencies with a leader, and with allusions to racism which were fashionable at the time.”6

The Young Mekas: Literature under the Nazis

What did Mekas do as the German armies swept through Biržai? In a postwar Soviet interrogation, his classmate Leonardas Matuzevičius (one of “the Six”) took credit for establishing an LAF command center in the town. There is no evidence that Mekas took part. But, according to Casper, soon thereafter, Mekas’s cultural life blossomed as he “ascended through the ranks of the collaborationist Lithuanian literary world,” and took part “in running two ultranationalist and Nazi propaganda newspapers.”7

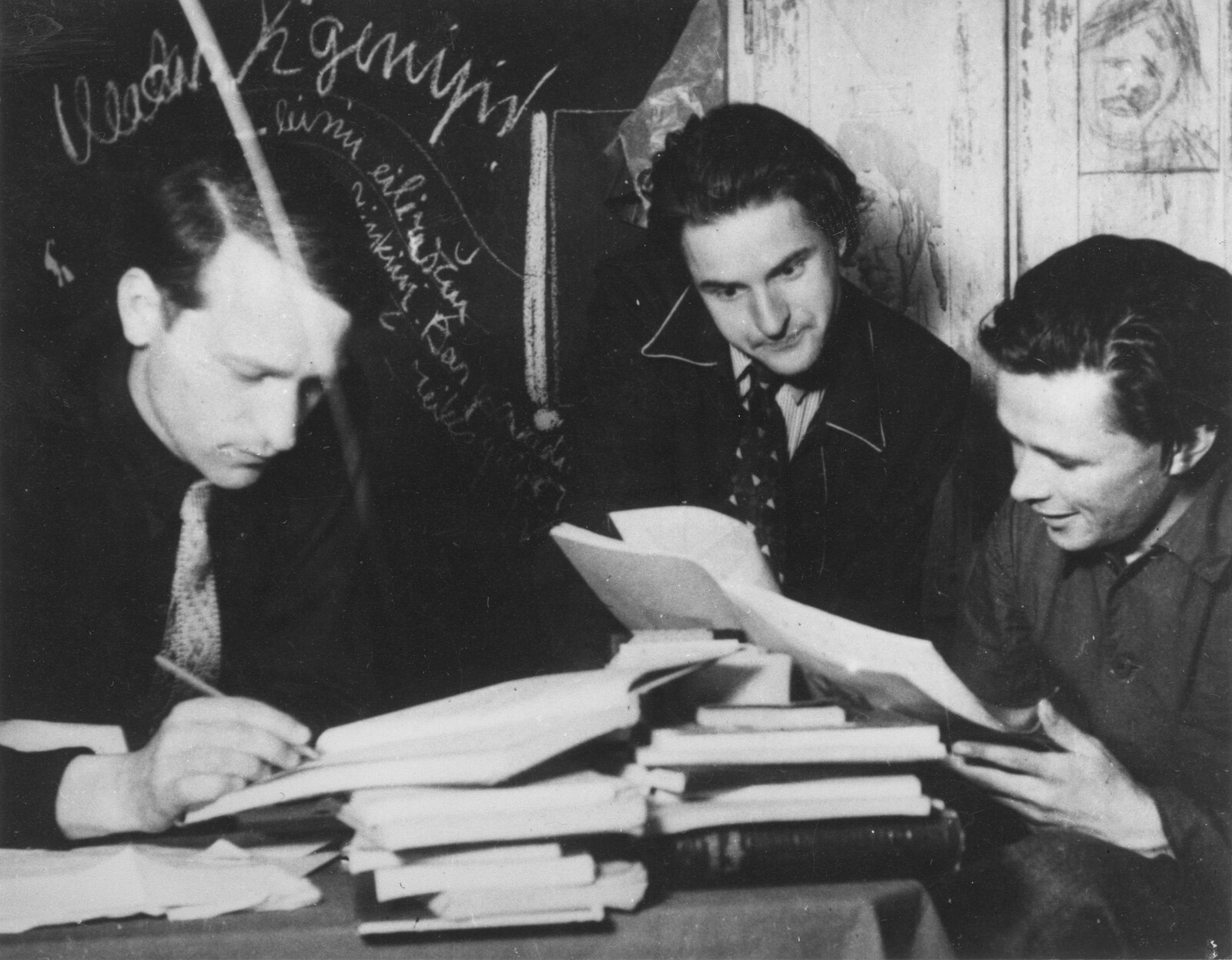

This remarkable achievement for someone who had not yet reached his twenty-second birthday when he fled Lithuania in 1944 requires closer examination. What were Mekas’s editorial activities and literary output, and what did it mean to work under foreign occupation? In his email exchanges with Casper, Mekas admitted that “calling myself editor-in-chief was obviously a bragging … [something] a young person put in his or her job application.”8 During a six-hour interview he conducted for the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM) in 2018, Mekas explained in some detail his work as a proofreader and writer for the cultural features in two newspapers. In the aftermath of the Nazi invasion, Mekas had found work at the aforementioned Biržai weekly newspaper. He does not appear in the editorial credits of the NBž, nor in the weekly Panevėžio apygardos balsas (The Voice of the Panevėžys District, henceforth Pab), a much larger paper, which he joined in 1943. Mekas is listed as one of the self-styled “Biržai literati” who congratulated the Pab on the paper’s hundredth issue.

Tellingly, while Casper admits that Mekas never wrote a single anti-Semitic sentence in the two newspapers in question, he never details what Mekas actually published. Given the charge of support for Nazism, it seems only fair to examine Mekas’s wartime writings in the two papers (which are both available online). The first poem he published in the NBž appeared on September 6, 1941, a satire which likened Soviet activists to Don Quixote tilting at windmills. Aside from mostly lyrical poetry, Mekas produced biographical sketches of cultural figures. In Pab, he published an effusive tribute to the leftist avant-garde poet Kazys Binkis, born near Mekas’s home village and later recognized as a Righteous Gentile (in 1988). He praised the atheist freethinker Jonas Šliūpas for his “humanism and tolerance” and commemorated Martynas Yčas, a Protestant liberal politician in the Russian Duma. There are several of what Casper characterized as “sharp essays,” mostly apolitical polemics among literati insiders. Mekas also penned a plea to halt the plague of alcoholism and save the nation, a common theme during the Nazi occupation (Pab, August 15, 1943). Not quite the texts one expects from an ultranationalist Nazi sympathizer. Mekas’s writings then and later strongly suggest that he disapproved of the fascist drivel penned by associates like Matuzevičius. This is as logical a conclusion as any in trying to understand why Mekas avoided parroting anything resembling Nazi-like ideology or anti-Semitic tropes. Describing the posting of anti-Soviet wall posters and youthful literary creations as “deep political activism” in support of Nazism is grossly misleading.

The collaborationist label that Casper pins on Mekas derives almost entirely from his work at the two Nazi occupation–era newspapers, so we should understand the historical context in which the poet first put pen to paper, that is, the situation of the Lithuanian-language press under foreign rule. The Smetona regime’s supervision of the press had been relatively lax. The Soviet occupiers of 1940 imposed, for the first time, totalitarian censorship policies. Portraits of Stalin and visions of a new, classless society became ubiquitous. During this time, some Lithuanian writers sought to evade censorship by producing tracts on noncontroversial topics, such as nineteenth-century poets. As the Soviets took over after the German retreat in 1944, the mustachioed Leader of Progressive Mankind reappeared as a front-page icon. In his interview with the USHMM, Mekas insisted that Soviet censorship in cultural matters had been far more intrusive than the restrictions under Nazi rule. Any reader of the period’s Soviet Lithuanian newspapers can easily see that Mekas was right. The differences stemmed from contrasting approaches to control of the press. The Soviets assigned the arts a specific, transformative task: according to Stalin, the intelligentsia should strive to be “engineers of the human soul.” For their part, the Nazis were mainly concerned with securing the economic potential of conquered territories and cared less whether supposedly inferior peoples accepted Nazi-think. Their tendency to give the arts considerable latitude allowed Mekas and others to include uncensored material on Lithuanian cultural life.

Nonetheless, while Mekas and other apolitical authors avoided explicit support for the occupiers, there remains the question of how readers responded to the front-page and editorial content of their newspapers. After 1940, toxic belief systems came to dominate Lithuania’s public space for the first time. A certain level of ideological contamination was unavoidable, but there is no way to assess its extent. There were no Gallup polls, but conversations with contemporaries and anecdotal accounts hint at the impact. Some people bought what the Soviets and Nazis were selling, others responded with avoidance strategies: reading between the lines for nuggets of real information about the war and the political situation; skipping the nonsense on the first page and turning to useful sections that affected their daily lives (prices, regulations, obituaries).9 A free press reappeared in Lithuania only in 1990.

During the final months of the German occupation, Jonas and Adolfas Mekas helped type up and distribute some anti-Nazi bulletins derived from BBC broadcasts, activity not unlike his teenage postings of anti-Kremlin wall signs. Soon after, however, Jonas’s typewriter was stolen, and he feared that the Nazi police might trace it back to his place. At this point, he had reason to fear the German authorities. Once again, some context is in order. The popular enthusiasm that greeted the Wehrmacht in June 1941 began to wane within months. For most Lithuanians, long-term Nazi rule was hardly the desired outcome of the war. Lithuanian leaders insisted that nothing should be done that would assist the Soviet military advance, but, when necessary, Nazi designs inimical to Lithuanian interests were to be frustrated: cooperation and/or resistance would have to be conditional. As a result, the German-Lithuanian relationship became increasingly ambivalent, even contentious. In the spring of 1943, Lithuanians massively sabotaged Nazi plans to mobilize an indigenous Waffen-SS legion. A year later, when Germans (falsely) promised to create what was perceived as a separate Lithuanian army, thousands volunteered. Cooperation with the major anti-Nazi armed groups operating in Lithuania was considered but proved impossible because their pursuits were inimical to Lithuanian goals: the Polish Home Army wanted Vilnius, while the Soviet partisans supported the Kremlin. Such calculations became moot as the Wehrmacht retreated in the summer of 1944. To sum up, if in June 1941 most ethnic Lithuanians experienced the first days of the Nazi occupation as a liberation, the final year of 1944 presaged a second foreign occupation. Mekas’s wartime predicaments can be understood, but not if one is content with a “simplified” history.

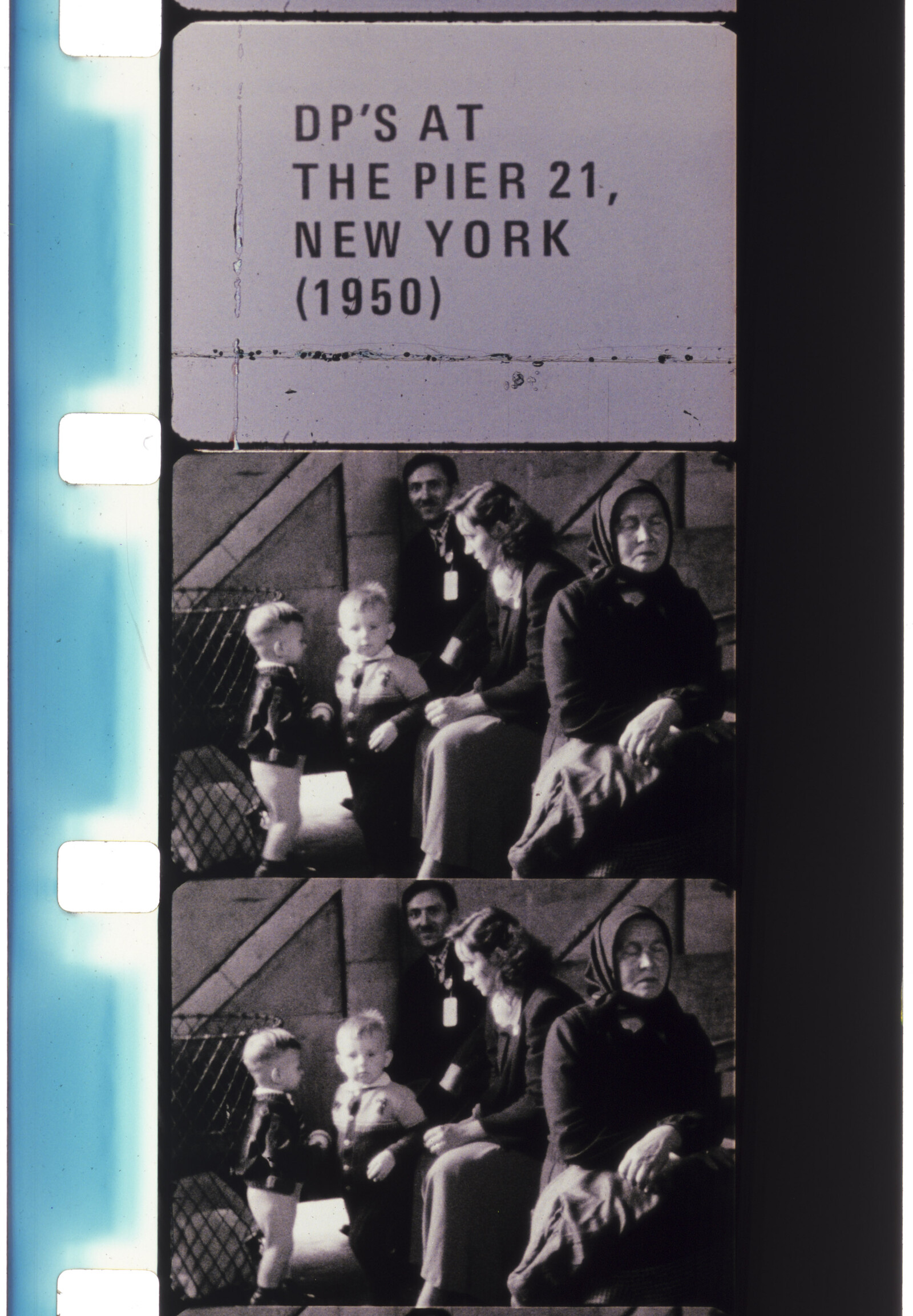

Photos from the displaced persons (DP) camps, 1945–49.

Photos from the displaced persons (DP) camps, 1945–49.

Mekas as Refugee: The Escape

As the Red Army advanced in July 1944, the Mekas brothers faced a decision. Jonas feared German arrest, but the approaching Soviets also evoked memories of the Kremlin’s repressions in 1940–41. My parents faced the same conundrum: there was some argument over whether to stay or go. The Soviets had deported my father’s cousin in June 1941 just before the Nazi invasion: Juozas Sužiedėlis and his two-year-old daughter survived Siberian exile, but his wife did not. In the end, many chose flight as the wiser option. Jonas and Adolfas obtained fabricated papers marking them as students on their way to the University of Vienna. From Austria, they hoped to reach Switzerland and find help from old friends of their uncle Povilas Jašinskas, a Reformed pastor, who had studied in Basel during the 1920s. However, the men were seized en route by the Germans and sent to do forced labor, which may have saved them from an even worse fate had they stayed home. In all, as many as a hundred thousand Lithuanians fled their homeland, most picking their way through East Prussia and continuing westward towards the Western Allies, careful not to travel too deeply into the Reich, where the men could be dragooned for labor, nor stay too close to the front and risk being overrun by the Soviets. In May 1945 my family reached friendly American troops and found safety.

To understand the motivations behind this dangerous trek into the Reich requires a factual if discomforting explanation of comparative threats. Needless to say, in the eyes of Lithuania’s surviving Jews, whose community had been effectively annihilated in the Nazi-led genocide, the return of the Red Army meant salvation. Dov Levin, one of the foremost historians of Lithuanian Jewry, aptly presented his work on Eastern European Jews in 1939–41 as a study in living under the rule of the “lesser of two evils.”10 Obviously, for them, the Kremlin was by far the lesser calamity. Even the Soviet deportations offered a far better chance of survival than Nazi rule. For Jews, thus, the question of relative dangers answered itself. But Levin’s formulation inevitably raises the question: a lesser evil for whom? The experience of non-Jews pointed to answers that were not as clear-cut. Despite selective repressions, non-Jews in German-occupied Lithuania did not suffer genocide. Nearly five thousand ethnic Lithuanians perished during the Nazi occupation, and tens of thousands more wound up as laborers in the Reich. The country’s Polish and Russian minorities endured worse in relative terms. But compared to the horror that had befallen the Jews, self-interested ethnic Lithuanians could conclude that, at least in the short term, the Germans did not yet pose an existential threat. It would be contrary to human nature if those who encountered first one, and then the other, of the most murderous regimes in European history did not engage in at least some cost-benefit postmortem.

Another factor encouraging flight was the illusion of a quick return. The Lithuanian generation that came of age during the interwar period hoped for a repeat of the Great War: Russian collapse, followed by a British and American victory over Germany, leading to favorable geopolitical conditions for the restoration of state independence. Refugee memoirs recount the desperate hope of another conflict: a nuclear-armed America forcing the Stalinists out of Eastern Europe. However fantastic in retrospect, at the time this hope was the only one that provided relief from visions of a bleak future.11 Strange as it may seem today, millions of people actually believed in a future in which they “may live out their lives in freedom,” one of the lofty goals articulated by Roosevelt and Churchill in the Atlantic Charter of August 1941.

Finally, many Lithuanians simply assumed that a second experience with Stalinism might be worse than the first version. On this point, they were not wrong. By the late 1950s most refugees learned more of what had happened back in their homeland. The vast majority of ethnic Lithuanians who died violently in the twentieth century perished during the five years following Germany’s surrender. After their return in 1944–45, the Soviets deported more than 130,000 people, mostly to Siberia and the Far North. Tens of thousands more were arrested, often tortured, some executed. At the same time, an estimated forty to fifty thousand people, including many civilians, died in the war between Lithuanian partisans and the various Soviet security forces. After Stalin’s death, Lavrenti Beria, the notorious Soviet police chief, reported to the Party bosses that more than a quarter million people had suffered one of these violent outcomes in postwar Lithuania.12 The Kremlin claimed to be fighting fascist bandits, of course, but the fierce Soviet pacification of the country targeted thousands of innocents. People who lived this post-1945 reality do not remember it as a liberation. In popular idiom, these years are known as the pokaris, the “afterwar,” an expression understood as carnage rather than peace. Some Lithuanians tend to adopt the pokaris as their own Holocaust, which it was not, but this massive and lethal Soviet terror was clearly a crime against humanity.

I surreptitiously visited my father’s village in 1969, the first physical contact with relatives left behind since the war. Uncle Vladas told me we were the lucky ones: the Soviets had turned up at the family homestead looking for my father. He led me to the family cemetery where one can still read the dates on the gravestones: 8 May 1945, VE-Day (the German surrender much celebrated in New York). But on this day, my uncle’s in-laws, including children, were massacred in clashes during the first phase of what would become a full-scale guerilla war. When Mekas visited Lithuania in 1971, family members reported that Soviet soldiers searched their premises repeatedly and on one occasion killed their livestock as retribution for not delivering the escaped brothers.

Jonas and Adolfas survived the final months of the war as laborers in factories and farms. Jonas’s Lithuanian-language diary/memoir, far richer in detail and more expansive than the English version,13 cites hunger and aerial bombardment as their daily travails until the war’s end, before their subsequent transfer to refugee camps in Hesse. My parents, like most refugees, hoped for a quick return, a dream they abandoned after a few years in the DP camps. They left for America in December 1948 on one of the numerous retrofitted troop ships. After Stalin’s death, they accepted the painful reality of a lost homeland and applied for US citizenship, mainly to assure prospects for their sons. Jonas and Adolfas Mekas left Europe in October 1949 as the DP camps emptied. This was to be a new stage in the arc of an extraordinary life. A disadvantaged village child, who, as a life-long bookworm, had acquired a remarkable grasp of philosophy, literature, and the arts, would now find fame within a new culture.14

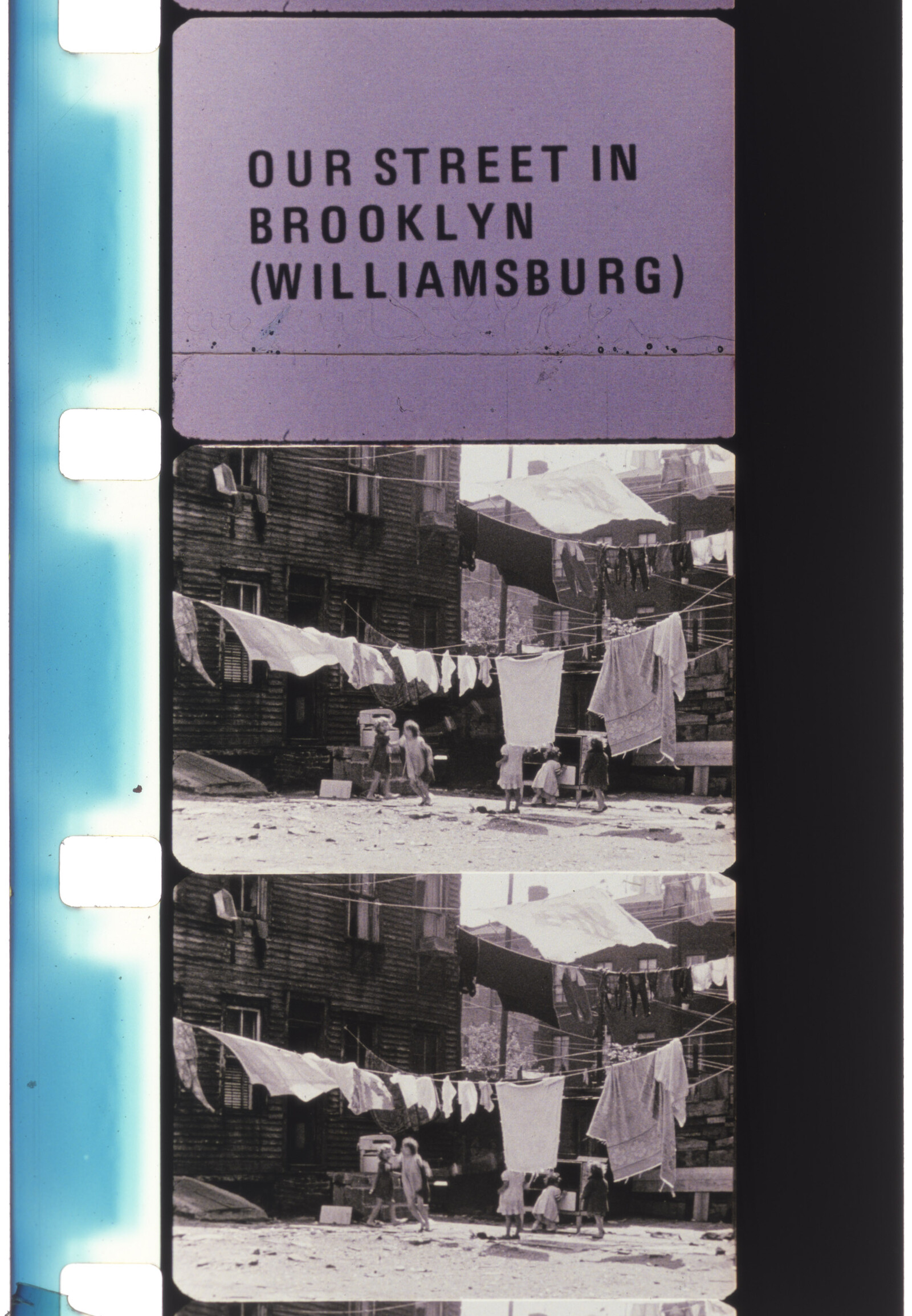

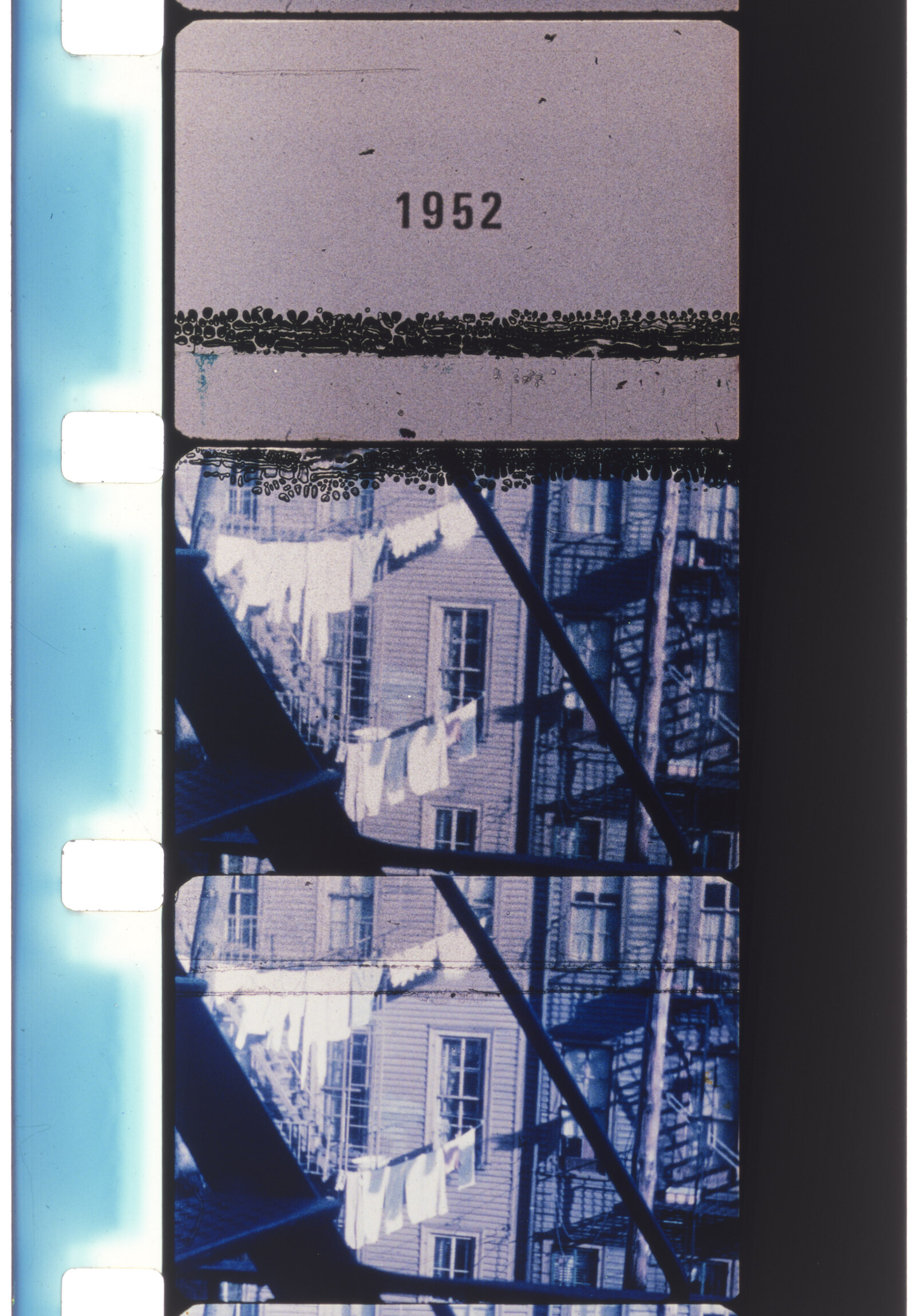

Stills from Jonas Mekas’s 16 mm film Lost Lost Lost (1976).

Stills from Jonas Mekas’s 16 mm film Lost Lost Lost (1976).

Mekas in New York: Despair and Hope in the New World

Casper’s claim that Mekas was a “typical” Lithuanian DP is far off the mark. It is true that during his first years in Brooklyn, Mekas was no stranger to the Lithuanian diaspora. My brother’s fiancée remembers the cinematic Mekas brothers and their literary friends as “a lively bunch.” But as Mekas settled into New York’s art scene, he began to spend most of his time with his newfound American friends and celebrities. Catholic Lithuanian leaders were wont to tag Mekas’s iconoclastic avant-garde companions as “Communists” who disrespected “national traditions.” Conservative anti-Communist DPs were enraged by the brothers’ visit to Soviet Lithuania, counting it as a betrayal. Others described Mekas as a bohemian.

Like most immigrants, he was torn, longing for a lost homeland which he recalled in his published reveries of his childhood, but also increasingly at home in his new country. As most people who have undergone the refugee experience know well, there is often a permanent, lingering sense of loss.

But in Casper’s Jewish Currents article, the American Jonas Mekas appears as a one-dimensional, reactionary prevaricator about his past. Mekas, he tells us, was a “Trump supporter,” although the filmmaker is known to have likened the former president to Vladimir Putin and ISIS and was put off by Trump’s attitudes towards immigrants and women. His Lithuanian memoir contains anti-war texts, sharp attacks on hypocritical ultra-patriots of his own community, and an abhorrence of “-isms” right and left. Casper’s other allegations against Mekas fault him for things he didn’t do or say: sins of omission. Mekas dodged confrontation. He never condemned the wartime activities and allegiances of people he knew. Compared to others, he did not suffer as much at the hands of the Germans. He avoided talking much about the specific suffering of the Jews, as evident in his interview with the USHMM. (Mekas did evoke the death of the Jews of Biržai in his memoir, relating “how we listened helplessly to the chanting dirge of the Jews driven to their execution, unable to help in any way,” a sentence in a passage bemoaning Nazi and Soviet barbarism in Europe.)15

Aside from what he presents as oversights, Casper employs the dubious tactic of guilt by association. Mekas was friends with some bad actors, such as his schoolmates who praised the Führer and promoted anti-Semitic tropes. Jonas’s brother Adolfas, a filmmaker in his own right known for satiric comedies, visited Germany with his wife in 1971 and had a friendly encounter with an old foreman from his wartime labor days. The artist had unnamed “lifelong connections to Lithuanian political and cultural figures” who shared his refugee experience. A seemingly innocuous association, but useful if one wants to align Mekas with pro-Nazi elements who found their way to the West after the war. Did Mekas encounter war criminals in his numerous interactions with fellow DPs? Was he literally in the same boat with them as he crossed the Atlantic in his stormy passage to New York? There is no way to be sure, of course, but there is little evidence that he was close to such people, or to “political leaders” among Lithuanian immigrants. Without knowing the actual degrees of separation, such connections, especially when casual, tell us little, but they can be useful in staining a reputation.

History Revisited: Collaboration, Nationalism, and Revisionism

Was Mekas a collaborator? An answer requires both a definition of collaboration (not so easy) and an understanding of the environment in which a particular society faced foreign rule (also difficult).16 As a pejorative, collaboration implies the betrayal of one’s own group. Accused collaborators of all stripes have invoked the “better us than them” defense, claiming that they prevented much worse by cleverly subverting the foreigners’ policies while pretending cooperation: “patriotic traitors,” according to one author.17 This is often a self-serving evasion, but one can also imagine a wide range of behaviors in real-life conditions: from slavish devotion to the occupiers, to providing apolitical educational or other public services within ever-narrowing constraints. My historian father taught university courses under Smetona, served as an official in the Academy of Sciences of the Lithuanian SSR after the Soviet annexation, and continued in the position for some time after the German invasion. Throughout he remained what he had always been: a Catholic sympathetic to Christian Democratic social teachings. People who knew him did not see him as a collaborator. A recent academic study on postwar DPs implies that work in a post office or a hospital during an occupation might be evidence of “collaboration.”18 This is not the only example of an unfortunate tendency to paint, with a broad brush, a world where schoolteachers and poets share the same culpability as jailers and killers.

As with collaboration, discussions of nationalism must deal with a range of meanings. Given his iconoclastic views, contrarian political positions, and impatience with kitsch-like patriotic cant, it is strange to learn that Mekas, in Casper’s words, “maintained a strong Lithuanian nationalist streak his entire life” (whatever that means).19 So, was Mekas a “nationalist”? Probably, if we include those who recognize the importance of attachments to place, of possessing a culture they can call their own, and find it difficult to accept foreign domination. These attitudes pretty much describe most Europeans since at least the end of the nineteenth century, but the spectrum of possible nationalisms is wide.20 Before the war there was Smetona, the anti-Nazi nationalist who once praised the French Revolution’s liberal ideas, a contrast to his enemies in the secretive fascistic Iron Wolf organization who espoused “blood and soil” ideology. Anti-Nazi resistance movements in occupied Europe were fervently nationalist, such as the French and Dutch, and the largest, Poland’s Home Army (which, notably, was not free of anti-Semitic excesses). During the war, some Lithuanian nationalists turned into murderers, some served in various posts under both the Soviet and German occupations, others observed the atrocities of the occupiers, and still others fought the foreigners. There are nationalists listed among Yad Vashem’s Righteous Gentiles: Ona Landsbergienė, the wife of a minister in the LAF provisional government (and the mother of Vytautas Landsbergis, Lithuania’s leader in 1990–92); Jadvyga Jablonskienė, whose brother headed the Vilnius city government during the first weeks of the Nazi occupation; Kazys Grinius, the country’s leftist president in 1926; Stefanija Ladigienė, an active Catholic leader and the widow of a general executed by the Soviets. Jablonskienė and Ladigienė were among the Lithuanian rescuers who were arrested by the Soviets during the pokaris.21 The point here is that while there exists a rich literature on nationalism, the nationalist label is, at best, inadequate when divorced from its historic context and attached to vastly dissimilar people. If Casper wants to paint Mekas as some sort of extreme “ultranationalist,” then he should say so and provide the evidence.

Casper, among others, is concerned about “revisionism” regarding the treatment of World War II in Lithuania. He attacks a certain “state-sponsored commission” for investigating both the “Soviet and Nazi occupation regimes,” thus “flattening the distinction” between Nazism and Communism.22 I assume Casper is speaking of the historical commission of which I am a member, so some facts should be clarified. In 1998, Lithuania’s president Valdas Adamkus convened an international body of researchers (with admittedly a most unwieldy title)23 charged with examining the history of foreign rule in Lithuania (1940–91). Under international law, there was a basis for treating the period as a whole.24 Since there were two occupying powers, separate working groups (subcommissions) were convened; they eschewed superficial comparisons between the Nazi and Soviet regimes, and after the commission was reconstituted in 2012, explicitly acknowledged the “distinct, unprecedented nature and scale of the Holocaust.” The subcommission on Nazi crimes includes scholars from Germany, Israel, and the US. I am chair of the Nazi crimes subcommission.25

An increasing number of ethnic Lithuanian scholars, some of whom have mastered Yiddish and Hebrew, now publish widely on the country’s Jewish past—according to Casper, a veritable “renaissance of Jewish studies.”26 Today they are authoring monographs, articles, collections of documents, and other scholarly materials on the Holocaust in Lithuania. For many of them, confronting the past has been a difficult journey. These mostly younger scholars have worked to move Lithuanian society forward towards a more inclusive history that entails a recognition of Jewish culture as an integral part of Lithuania’s past; an understanding of the Shoah as a central event in history; and an examination of the behavior of the Lithuanian people during the Holocaust. These goals are obviously aspirational and more needs to be done.

What Casper and some other American commentators fail to acknowledge is that this process is largely financed by the Lithuanian government through state-supported universities, academic institutes, research centers, museums, the ministries of culture and education, and similar institutions. Hundreds of teachers have traveled to Yad Vashem on this same government’s dime, and there are numerous educational programs on the Holocaust, Jewish history, and the promotion of tolerance. Foreign NGOs, the EU, and international institutions, such as the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance, have contributed significantly. As would be expected, there is strong pushback on all of this from right-wing forces in Lithuania, which has inflamed culture wars that rival in intensity similar conflicts in the United States and elsewhere. The LAF and the June Uprising in particular have spawned bitter polemics.

Post-Soviet (and now uncensored) historical research in Lithuania reflects Baltic perspectives and often differs from narratives found in many Western studies. It gives voice to non-Jewish peoples, of whom Mekas was one. In some sense, it is “revisionist”—that is, new scholarship based on previously inaccessible evidence. This does not mean denial of what is already known, nor does it negate the enormity of the Holocaust, but rather adds to the understanding of how a people were destroyed in a genocide, without minimizing the suffering of those who escaped annihilation. All this might discomfort people with preconceived stereotypes about the Baltic peoples and their past.

There is another problem to consider, one more difficult to confront, since it reaches into a world of deeply emotional memories and contrasting experiences. A serious obstacle to an acceptance of an inclusive history in Lithuania stems from the fact that there are few shared wartime experiences that produce good feelings (for example, rescue), and many more that are divisive. The nexus of Nazi and Soviet crimes complicates discussions. Conflicting stories of heroes and victims do not allow for soothing narratives. Most of the “anti-fascists” encountered by Lithuanians during the pokaris were Stalinists, some with nasty reputations. Small wonder that references to the Grand Alliance and “anti-fascism” do not, in their case, automatically evoke warm feelings.27 Among the postwar freedom fighters were a number of perpetrators who had served in German-organized police battalions, so that many Jews find it difficult to embrace the heroic memory of the anti-Soviet guerrillas, affectionally known as the “forest brothers.” The harsh reality is that Jews and Lithuanians inhabited different worlds of wartime and postwar experience and, as a result, acquired sharply contrasting collective memories. What might encourage further misunderstandings is the fact that the Western narratives of the war, particularly those of Americans steeped in Spielberg films and stories of the “Greatest Generation,” remain largely irrelevant to the experience of many peoples who suffered the war on the Eastern Front. These issues are emotive and create a difficult relationship with both the Other and the past itself. But it needn’t be so forever. Perhaps, more than seventy-five years after the end of World War II, we might come closer to an understanding of how different peoples were affected and how we are all still shaped by those events.28

There are historians and commentators, primarily in the US, Western Europe, and Russia, who vehemently oppose any suggestion of comparison between Nazism and Stalinism. (I prefer the latter term rather than “Communism,” because this was the form of Soviet power that Mekas encountered.) Nevertheless, a body of respectable scholarship has studied comparative totalitarian systems, albeit from varying perspectives. Hannah Arendt tackled the problem in her classic Origins of Totalitarianism (1951), as did, in later years, Carl Friedrich, Sheila Fitzpatrick, Moshe Lewin, and Ian Kershaw. More recently, Robert Gellately, Timothy Snyder, Alan Bullock, Vladimir Tismăneanu, and others have written insightful comparative analyses of Nazi and Stalinist systems. It seems impossible not to see striking similarities: the mass murder of targeted groups as a legitimate path to achieve utopian goals; the worship of charismatic leaders; the ubiquitous one-party police state; control of cultural expression. To acknowledge the obvious is hardly sinister “revisionism.”

During the Second World War, states and resistance movements often chose one evil to confront another, facing, at times, morally compromising choices. There are many possible responses regarding the ideology and goals of a problematic ally, from reluctant accommodation to total identification. Befriending one devil to fight another is one thing; embracing the devil’s worldview, quite another. There were too many notable intellectuals, artists, and literati who either justified or embraced murderous extremist movements. To name a few: American architect Philip Johnson lauded Hitler, Ezra Pound trumpeted fascist ideology, and Jean-Paul Sartre praised Mao. Martin Heidegger joined the Nazi Party and Pablo Neruda remained for years a card-carrying Stalinist. A motley crew deserving at least a mention on the wall of shame.

Jonas Mekas was not one of them.

Michael Casper, “I Was There,” NYRB, June 7, 2018 →.

Michael Casper, “World War II Revisionism at the Jewish Museum,” Jewish Currents, April 21, 2022 →.

Letter to The New Yorker, May 23, 2022.

Barry Schwabsky and Michael Casper, “On Jonas Mekas: An Exchange,” NYRB, July 19, 2018 →.

Specifically, the Soviet-German nonaggression treaty of August 23, 1939 (the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact), the Treaty of Friendship of September 28, 1939, and the commercial agreements of January 10, 1941.

As stated by former LAF leaders Juozas Brazaitis (Ambrazevičius) and Pilypas Narutis, “Lietuvių aktyvistu frontas,” in Lietuvių enciklopedija, no. 16 (Boston: LE leidykla, 1958), 27.

Casper, “World War II Revisionism.”

Citation provided by Mekas’s family and friends who had access to Casper’s email correspondence with the artist. The information citing him as “editor” found in a short encyclopedic entry in 1997 and other sources almost certainly comes from information supplied by Mekas himself, which first appeared in a 1959 émigré multivolume encyclopedia (“Mekas, Jonas,” in Lietuvių enciklopedija, no. 18 (Boston: LE leidykla, 1959), 148.)

Some responded with humor, as in the anecdote about the two major Soviet newspapers, the Party organ Pravda (The Truth), and the government paper Izvestiya (The News): “There is no news in The Truth and no truth in The News.”

Dov Levin, The Lesser of Two Evils: East European Jewry under Soviet Rule, 1939–1941 (Jewish Publication Society, 1995).

As in the memoir of the refugee and later president of Lithuania, Valdas Adamkus: Likimo vardas—Lietuva (Fate’s Name—Lithuania) (Kaunas, 1998).

“Beria’s Report to the Presidium of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the USSR,” May 8, 1953, listing Lithuanians who had “suffered repression.”

Jonas Mekas, Žmogus be vietos: nervuoti dienoraščiai (Man without a Place: Nervous Diaries) (baltos lankos, 2000).

In challenging Mekas’s account of his own education, Casper claims that Mekas’s high school graduation and studies at the University of Mainz are proof that the artist lied about being “largely self- taught.” Mekas, like many village children with literate but minimally educated parents, enrolled in elementary school late at age nine (which in Lithuania comprised four grades). He was a voracious reader who eventually tested into the appropriate grade for his age. Mekas struggled as an older student but finally entered high school when he was seventeen. He took some college courses in Germany as a displaced person but never earned a degree. To challenge a nonagenarian about this seems ungenerous at best.

Mekas, Žmogus be vietos, 389.

In one reasonable definition, the collaborator must be willing “to grant the occupier authority” in a context of an “uneven distribution of power,” rather than merely providing “expertise and information.” Jan Tomasz Gross, Polish Society under German Occupation: The Generalgouvernement 1939–1944 (Princeton University Press, 1979), 117, 119.

As in the title of the journalistic survey by David Littlejohn, The Patriotic Traitors: A History of Collaboration in German-Occupied Europe, 1940–1945 (Heinemann, 1982).

David Nasaw, The Last Million: Europe’s Displaced Persons from World War to Cold War (Penguin Books, 2020).

Casper, “World War II Revisionism.”

See Alan Ryan’s thoughtful review essay “Whose Nationalism?” NYRB, March 26, 2022 →.

As an interesting aside, one should note that rescuers in all Nazi-occupied countries were a diverse lot. Some brave souls were known anti-Semites (a point well elaborated by historian Nechama Tec), which seems counterintuitive—but only if one forgets that most American abolitionists were racists by today’s standards. To complicate matters further for those seeking a simple history, Timothy Snyder has cited the case of Andrey Sheptytsky (Andrzej Szeptycki), the Ukrainian metropolitan of the Greek Catholic Church who “welcomed the Nazis and saved Jews” (Timothy Snyder, “He Welcomed the Nazis and Saved Jews,” NYRB, December 21, 2009 →). A thorough analysis of this cleric’s thinking can be found in John-Paul Himka, “Metropolitan Sheptytsky and the Holocaust,” Polin, no. 26 (2013).

Casper, “World War II Revisionism.”

The International Commission for the Evaluation of the Crimes of the Nazi and Soviet Occupation Regimes in Lithuania, known in short form as the International Historical Commission.

The Lithuanian parliament’s declaration of independence of March 11, 1990 was a restoration of a status that had existed de jure since 1918. The major Western powers never recognized the incorporation of the Baltic States by the USSR and had continued to accredit their diplomatic missions throughout the postwar period.

An overview of the Commission’s work is in my article “The International Commission for the Evaluation of the Crimes of the Nazi and Soviet Occupation Regimes in Lithuania: Successes, Challenges, Perspectives,” Journal of Baltic Studies 49, no. 1 (2018).

Casper, “World War II Revisionism.”

Putin is now playing the anti-fascist card in Ukraine with brazen hypocrisy, but this has roots in the Soviet past, as explained in Timothy Snyder, “We Should Say It. Russia Is Fascist,” New York Times, May 19, 2022 →.

A good example of an honest confrontation with the past is Jeffrey Gettlemen, “On Poland-Ukraine Border, the Past Is Always Present. It’s Not Always Predictive,” New York Times, April 14, 2022 →.