This is a story that either happened a long time ago, and has passed out of telling but not out of blood-memory, or will happen one day—in some way.

—Sharanya Manivannan, “Sanguinary” in Incantations over Water1

Ink in the Fish

In the early hours of July 17, 2020, I had a dream I was cooking with my amma (Tamil for “mother”). We were together in my childhood home in Connecticut, making meen (fish) cutlets. Fish cutlets are a variation of bolinho, the deep-fried and breaded Portuguese fish-and-potato croquette. In Sri Lanka, meen cutlets fall into the culinary genre of “short-eats”— handheld bites prepared for entertaining guests or a quick snack on the road.

My amma has given me her meen cutlet recipe in person multiple times, and now once in a dream. I never wrote her directions down, but every telling remains sensorially clear. Each scene hosts an audience of unmeasured ingredients. Cloudy, unmarked plastic canisters of spices and leftover loose curry leaves watch for hands and tiny spoons. The potatoes wait to be diced and boiled. Then, they anticipate being mashed together with tinned mackerel in a mixing bowl and combined with finely chopped curry leaves and green chilies, and onion and mustard seed, cumin seed, lime juice, salt, black pepper, chili, and curry powder. In the foreground, a pile of Progresso Italian-style breadcrumbs is spread out over two layers of an old Tamil or English newspaper that my appa (father) has long since finished reading. My amma, center stage, makes snarky, confident instructions in mixed Tamil and English. While she talks, my fingertips trace small inlets in the breadcrumbs.

As a child, I never thought twice about consuming the newspaper ink and wood-pulp fibers that bled into the cutlets’ pre-fried insides and bristly, deep-fried outsides. Both pulp and ink were just two more ingredients in my childhood, unmeasured but always present. Newspapers accompanied food as intimately as the background noise of mourning and uncertainty filtered through my amma and appa’s hushed tones and loud cries on telephone calls with loved ones back home. Between 1984 and 1996, none of us visited my parents’ respective villages of Kalmunai and Nallur in northern and eastern Sri Lanka. The last time we traveled there as a family was in 1983, just before the anti-Tamil riots of July. From what my amma and appa tell me, I spent most of my days there that June running outside with other children, being chased by dogs in the garden, carried by doting aunts and uncles, and hand-fed by my ammamma (grandmother) or amma.

My first clear memories, back in Connecticut, are of my amma hoisting me up onto the countertop to watch her make cutlets. Later, as a six-, seven-, and eight-year-old, if I was lucky, I would be allowed to help her dip two or three of the small, molded balls of cooked fish and potatoes into a bowl of egg yolk to coat them, and then roll them gently over the small hills of breadcrumbs. She would place the raw, breaded cutlets onto a newspaper-lined plate, which she would then bring out to the back deck to fry.

The bubbling amber sea of vegetable oil in her outdoor Fry Daddy terrified me. From behind the armor of my amma’s body, I would watch her gently submerge the cutlets with a slotted metal spatula. After easing them down, she would let the boiling liquid saturate their insides and turn their skins to a warm golden brown. After a minute or two she would retrieve them, one to three at a time, and place them on the newspaper, careful not to break their delicate molds.

At the Threshold

Watching my amma make meen cutlets—and eating them hot out of the fryer on our cold, Connecticut deck while the ink of Tamil and English scripts bled into their makings—formed my only childhood memories about a Sri Lanka marked by stability and constancy. From 1983 to 2009, the government of Sri Lanka and the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) fought battles over their competing, insatiable dreams of ethno-nationalist control. Their warring desires were unleashed at the expense of civilians, with the violence disproportionately devastating the lives of Sri Lanka’s Tamil and Muslim minorities.

Four months into the Covid-19 pandemic, my elderly parents, both physicians, continued seeing patients. As more and more people around them died or fell sick, my anxiety about their exposure to the virus intensified. It was no surprise, then, that my amma and her cutlets visited me in my dreams that July. In my own home, three thousand miles away in Northern California, I had all of the ingredients, but no measurements. I decided to call my amma and ask her to recount the recipe once more. Only this time, I wrote it down.

Three and half months later, on October 29, my appa tested positive for Covid. My amma’s positive test followed a day later. Appa’s oxygen levels fell rapidly, and he was admitted to the hospital on day six with Stage 4 pneumonia and put on oxygen. Three decades earlier, he and my mother migrated to the United States to complete their medical residencies at the same hospital.

My amma, with only occasional wheezing and a loss of smell and taste, was home alone for the first time since she and my appa married. She lost her appetite and stopped drinking water and taking her daily vitamins and medications. I took a red-eye from San Francisco to Connecticut on day ten, and when I greeted my mother outside their house with my luggage in hand, she immediately told me to come inside and have a wash after the flight. I told her that I could not because she had Covid, and she became frustrated that I had even travelled to see her. In her words, “What is the point of you coming all the way here if you can’t even come inside and eat?” I didn’t have a good response. She was right; I felt inconsolably helpless. What good could I possibly do for her if I could not even enter her house to eat?

Eventually, because it was unseasonably warm for early November, she joined me on the deck and brought out some broken-up pomegranate, telling me that it was the only thing she felt like eating. I gave her some coconut water and told her that she needed to drink. We sat there in distant patches of the brisk sun, drinking coconut water and eating pomegranate seeds until she got tired and went inside to nap.

Later that week, when it was time for her to pick up my appa from the hospital, I followed her in a separate car only to watch her pull into the parking lot of a department store less than half a mile from the hospital. She could not remember how to get there. I got out of the car and told her that it was okay. She has not driven since. When I left Connecticut, she blew me a kiss from the threshold of the garage door and asked me if I was coming home for Christmas. I blew a kiss back to her and told her I would have to wait and see.

Blood-Memories

Sometimes, after an intense event, we are temporarily given a glimpse into that which we do not yet know. Nothing of the calm that follows gives away the revelation that came, or the devastation that remained.

—Sharanya Manivannan, “Marigram,” in Incantations over Water2

When I found out I was pregnant a month and half after leaving Connecticut, I chose not to tell my amma, who was still recovering from her brain fog. Instead, I would talk to her about cooking and her childhood. I asked for her cutlet recipe again and again but did not mention that I could not eat tinned mackerel because of the mercury coursing through their bodies. She told me about her own amma’s cutlets—about how, when she was thirteen years old, her mother taught her how to make them. If there were no breadcrumbs to buy in Kalmunai town, her mother would put out pieces of bread in the hot sun and dry them out, smashing them to a crisp. They cooked cutlets with fresh fish back then. Every day, her father would bring home fresh fish caught by fishers from Kalmunai Beach, about a mile or so from their house. Other days he would bring home kanivai (cuttlefish) and nandu (crab), and her mother would cook them for her and her older brothers. On weekends the children would walk their two dogs to Kalmunai Beach. Other days, when not in school at Carmel Convent for girls, my mother would help her amma care for the baby chickens they were keeping in a small incubator on the dining room table: black, brown, white lagoons, and another variety called Plymouth, as my amma’s elder brother would later fill in.

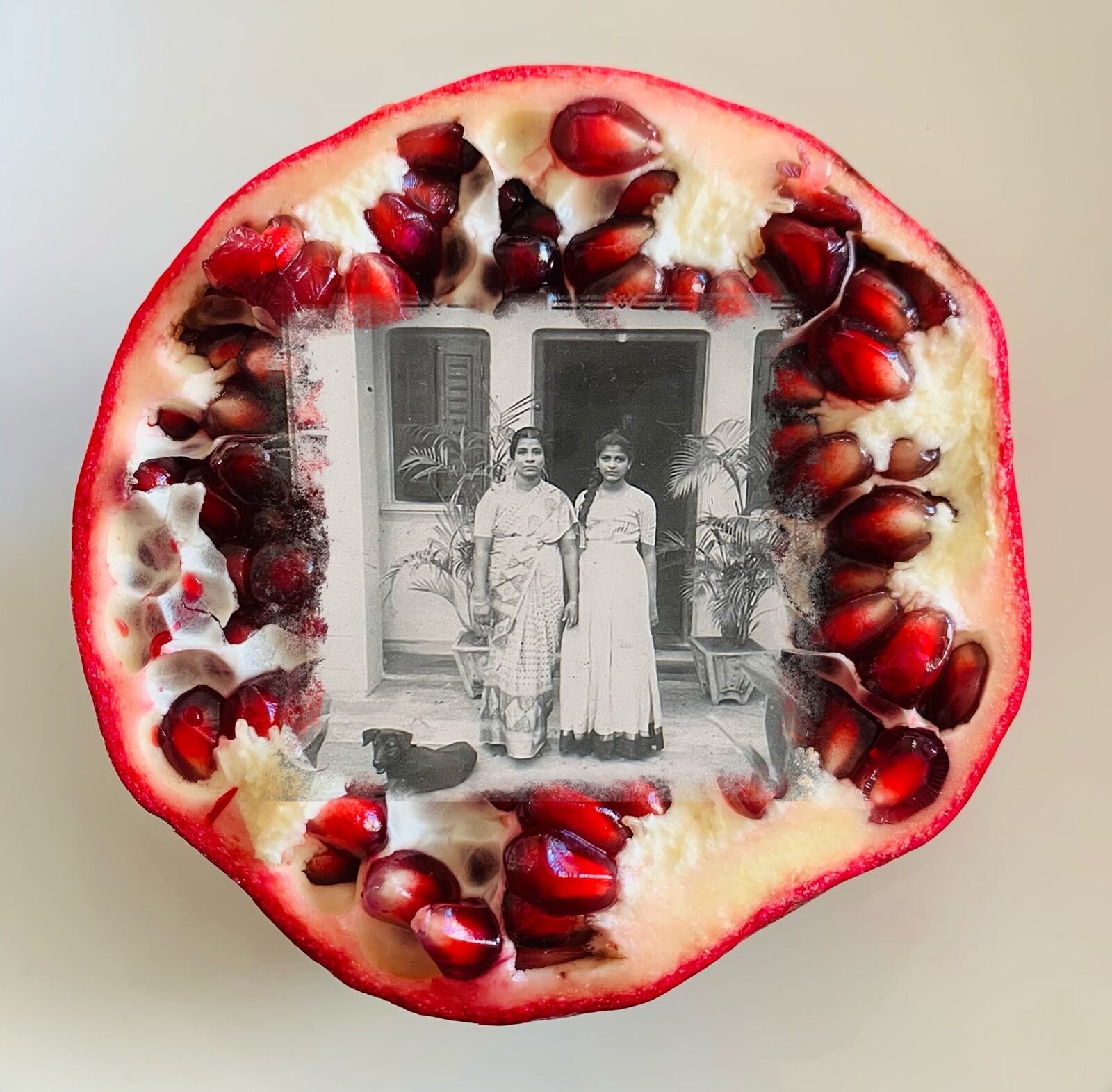

Bursting pomegranates in the sun. Author’s mother with her own mother outside their home in Kalmunai. Photograph from the author’s family collection. Estimated date: 1960–64. Image compilation and back layer image by the author.

On December 22, 1964, when my mother was seventeen years old, a cyclone devastated Kalmunai, Batticaloa, Mannar, Trincomalee, and other coastal areas in the north and east of Sri Lanka, then called Ceylon. She recalled how the storm felled all the coconut trees along the water. With the groves downed, they could see the coastline clearly from a mile away. The stormwater had come up to the steps of their house, but not inside. In that sense they were spared, but so many neighbors in their town and in nearby villages lost their lives and homes. Later, she would tell my niece and sister how her amma and appa had opened their home to those who had been displaced by the damage.

Like the tiles that flew off their roof that December, our winter 2020 conversations leapt across time, forming a never-ending ocean; I knew how to ask contributory streams of questions so that we could talk about anything except the changes in my body. The stories also went on because perhaps my amma was eager to respond—a steady and welcome distraction from confronting the changes in and lack of control of her own body.

After seeing a heartbeat on a late January ultrasound two days after my fortieth birthday, I told my amma and appa that I was expecting. Two weeks later, on my amma’s seventy-fourth birthday, it was confirmed that I was miscarrying. As I lay alone in the emergency room, bleeding on a different ultrasound table, I thought of how, when I was in grade school, I had lain next to my amma in bed as she recovered from her hysterectomy. She, like me now, had a uterus that was deemed myomatous. For years she had endured severe cramping and bleeding, and because she was done having children, her doctor recommended removing her uterus and the smooth tumors it held. The surgeon recorded the procedure and sent her home with a copy of it on VHS. Together, in her bedroom, we managed to watch it for a few minutes. It was the first time I had seen the insides of a body. But it would not be the last.

I also thought of a story that my mother had told me recently, in those months of brain fog before I learned that I was pregnant. She talked about the time she learned to cook meen kuzhumbu (fish curry) on her own. When she was a teenager, her amma had traveled alone from Kalmunai to Jaffna, in the north, to cook and care for her older sister and their family. Her sister was recovering from her own hysterectomy. Alone in the ER, I ached for my sister, with whom I share the diagnosis of living with endometriosis and the collective experience of four endometrial ablation surgeries. I thought, let this blood flow from my womb tonight. And take with it this unending devastation. But leave behind my blood-memories and bloodlines. In my sanguinary trauma, I did not know the future and the necessary bonds they would lead to. But somehow, I knew I would need them in the months to come. Two months later, I would make my amma’s cutlets. Six months after that, I would make them again. Each time, they tasted more and more like the ones I had eaten as a child.

From Ink to Blood to Fish

If we let go of the family tree and instead model relating on eating, being generative is not about having offspring, but about cultivating crops. If we do not focus on the companions with whom we sit around to table, but on to the foods that are on the table, we find that our love for them harbors violence, while our devouring may go together with gratitude. There is something complicated to do with how, in eating, individuals and collectives relate.

—Annemarie Mol, Eating in Theory3

In July 2021, I returned to Connecticut to visit my amma and appa. There, she gave me her 1964, revised fifth-edition copy of the [Ceylon] Daily News Cookery Book edited by Hilda Deutrom. She brought the book with her to the United States when she left Sri Lanka in 1973 and had used it throughout our childhood to make us love cake, beetroot and spinach ribbon sandwiches, milk toffee, and caramel pudding. There are stains on its red cover and the binding was taped with eight clear pieces of cellotape. But the original bookmark—an ad for ““Housewife’s Choice”“ V.B.F.” Pure Creamery Butter—somehow remains affixed within its seams. The first three advertisements in the edition are for gas cookers: “Gas is your reliable assistant, loyal friend, and faithful servant. Therefore, use gas.” Towards the end of the book, I found another advertisement, for Cooks-Joy vegetable cooking oil: “No cook worth her salt will settle for less.”

I have not made my amma’s cutlets since September 2021. But I think about them often as the ink from my childhood continues to haunt my blood. Since 2019, Sri Lanka’s president, Gotabaya Rajapakse, along with his now former prime minister brother, Mahinda Rajapakse (who also used to be president), have steeped the country’s civilians in an unrecoverable economic crisis through a series of longstanding policies and practices of militarization, ethno-nationalist violence, and corruption. Food prices have inflated to unmanageable heights, life-saving medicines and medical equipment are no longer available, and imported gas, diesel, and petrol for cooking, transportation, and daily life are docked on cargo ships off the island’s coast. The goods remain unloaded; there are no dollars in the country to pay for them. Fishers, who would have caught the kind of fresh fish that my amma and her amma cooked at home, cannot go out to sea because there is no diesel for their trawlers.

As of May 1, 2022, one kilogram of potatoes, which cost 140 Sri Lankan rupees ahead of the 2019 presidential elections, is now over 220 rupees. Tinned fish, once 231 rupees, costs 800 rupees. A cylinder of gas, once 1493 rupees, if even available, is 4,860 rupees.4 Members of civil society have demanded the abolition of the executive presidency. But the recent reinstatement of majoritarian-appeasing prime minister Ranil Wickremesinghe, combined with continued assaults and arrests of protesters, have suggested that the worst is yet to come.

In the opening pages of my amma’s Daily News Cookery Book, I found the following inscription collected from a previous edition:

Good cooks thrive best in the wholesome atmosphere of good homes. Conversely, domestic felicity is usually much beholden to a refined taste in what is crudely described as “feeding the brute” … A country’s culinary prowess is often an index of its domestic well-being.

While I continue to long for the warmth and texture of her meen cutlets in my mouth, when there is no gas to heat them to a golden brown in Sri Lanka, when the politics of home dismembers the only molds of what I knew as stability and constancy, my hunger for blood-memories becomes too violent to stomach. Until then, I must assure myself that I and other daughters of mothers and grandmothers in Sri Lanka will make fish cutlets again. For one another, and together, in and with the fish in the sea. Our makings will hold traces of ink and blood. But one day, it will happen. As my amma told me, “Do and then see. Nothing will happen to you when you put something in your mouth.” We should settle for nothing less.

Sharanya Manivannan, Incantations over Water (Westland Publications, 2021), 113.

Manivannan, Incantations over Water, 57.

Annemarie Mol, Eating in Theory (Duke University Press, 2021), 125.

Nadia Fazlulhaq, “People Fed Up as Essential Food Items Soar in Price by 200–500 percent,” The Sunday Times, May 1, 2022 →.