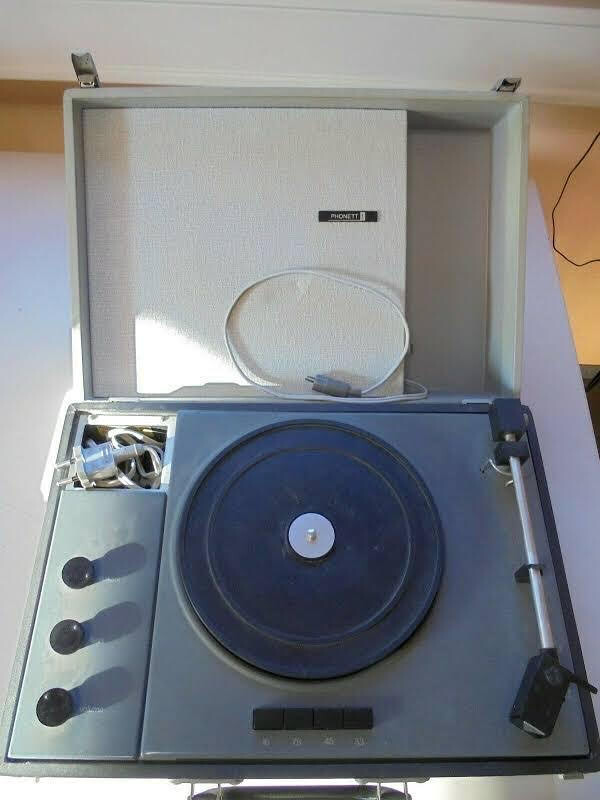

As soon as I started working, I would buy myself a turntable. I was set on it. Not right away, of course. With my first paycheck as a recent university graduate, I would treat my parents to eat at our family’s favorite restaurant. But if I saved a quarter of my following three monthly paychecks of 198 pesos, by the beginning of the following year, one of those turntables from the German Democratic Republic that had spent decades accumulating dust in the capital’s stores would, at last, be mine. It didn’t matter to me that humanity was moving on, en masse, to the crystalline sounds of CDs, or that, months before, the Berlin Wall had fallen. CDs were still an urban Cuban legend, and of the clamorous falling of that wall, only a vague buzz reached Cuba, a place that was more of an island than ever in those days. My dream of at last having a device that would play back any music I wanted seemed viable. Although not quite. I wasn’t going to listen to any music I wanted. If anything, maybe a few domestically produced records as dusty as the turntable I planned to buy myself and some classical music sold at the Czechoslovakian House of Culture, an institution that was increasingly becoming a relic of the past. A past in which expressions like “Soviet sphere” and “Soviet bloc” made sense.

However, and without any effort on my part, my seemingly modest ambition turned into an unattainable utopia. Then, it turned into nothing at all. But at least, after my first month of working at the cemetery, I was able to invite my parents to eat at El Conejito. It was the night of October 9, 1990. I remember because, as we were settling in at the restaurant, Cleo mentioned that it was John Lennon’s birthday. That night, I was unaware that the country that manufactured my beloved turntable had disappeared just days before into a union with its former rival, the Federal Republic of Germany. Nor did I know that it would be the last time I would eat at that restaurant. Or that soon enough, even the very notion of a restaurant would enter a phase of extinction. I, who thought that with that dinner I was celebrating my debut as an employed person, was actually bidding goodbye to the world as I had known it until then.

For our family, that dinner was the end of the world that had been socialist prosperity, an oxymoron that was made up of nearly endless lines for nearly everything, horrible public transport, and the forced ascetism of the ration card. A prosperity in which meat, seafood, and beer were absolute luxuries, but in which at least rum and cigarettes were plentiful. A world in which anything relating to food services was a sadistic enterprise and bureaucracy was Kafkaesque to such a degree as to infuse this writer’s works with new meaning. A choreographed poverty for which we would soon develop a fierce nostalgia.

The following months would be ones of a prodigious quantity of disappearances. First, the rum and cigarettes disappeared. The rum disappeared from lunch counters, leaving the bottles of Soviet vodka at the mercy of the boozers who had not noticed them until then. Later, vodka also disappeared. Not food. Food had disappeared from lunch counters ever since the 1970s: what it did was reappear intermittently, more or less. Until, at a moment that was difficult to pinpoint, that intermittence also disappeared. Something similar happened to toilet paper: after having an evasive relationship with our asses for years, it came to be definitively replaced by newspaper. (Some, with a more vengeful streak, recurred to the pages of the Socialist Constitution, of the Programmatic Platform of the Cuban Communist Party, or of the complete works of Marx, Engel, and Lenin printed by the Soviet publishing house Progreso on pleasant Bible paper).

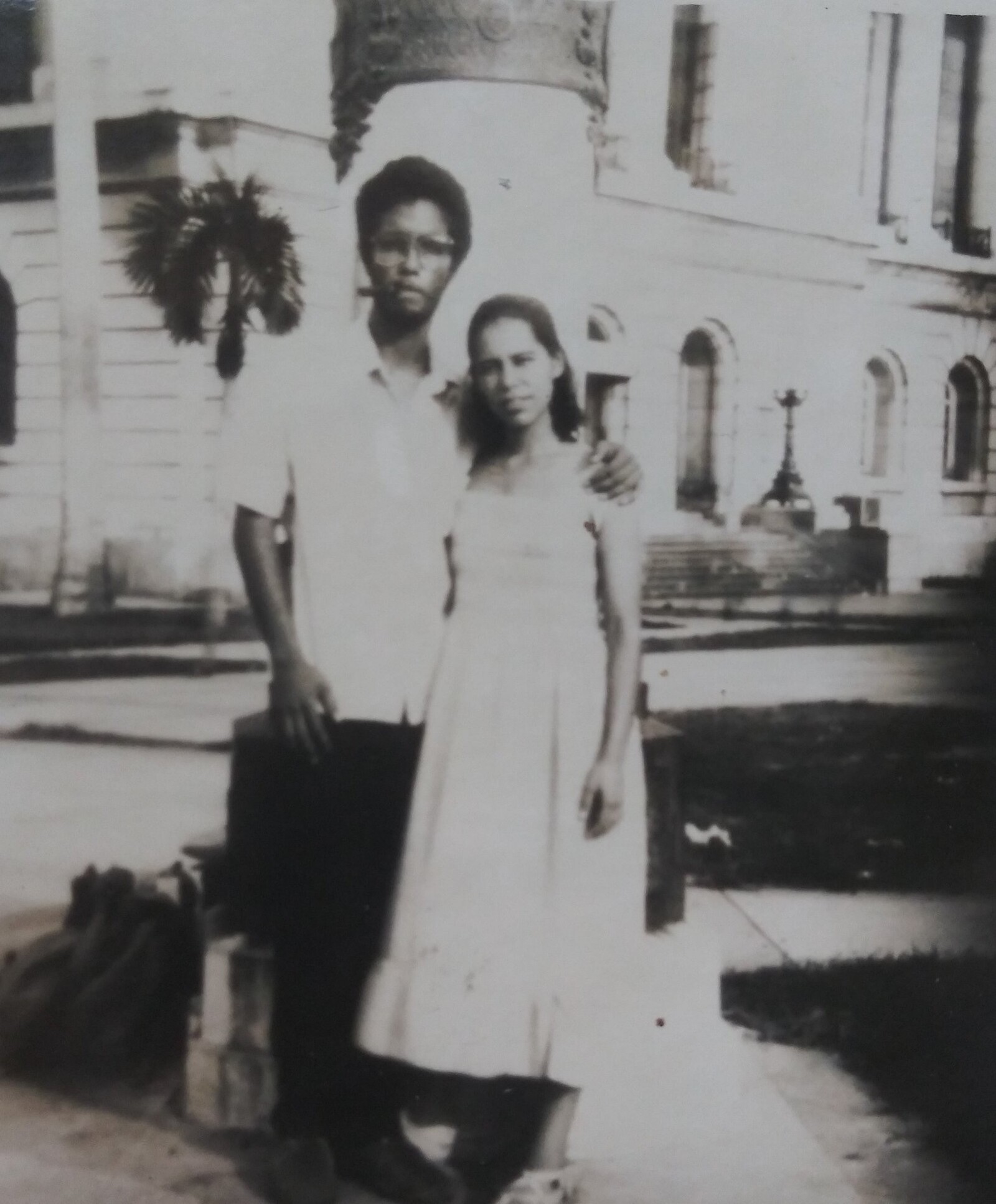

With my girlfriend and friends after one of the monthly “Waiting for Guttenberg” literary gatherings, Quinta de los Molinos, Havana, 1994. Image courtesy of the author.

Not long after, public transport would disappear almost entirely. The buses that used to come every half hour started to come every three or four hours. Many of the bus routes disappeared without a trace.

Porch lights also disappeared.

As well as any outdoor furniture.

And cats.

And fat people.

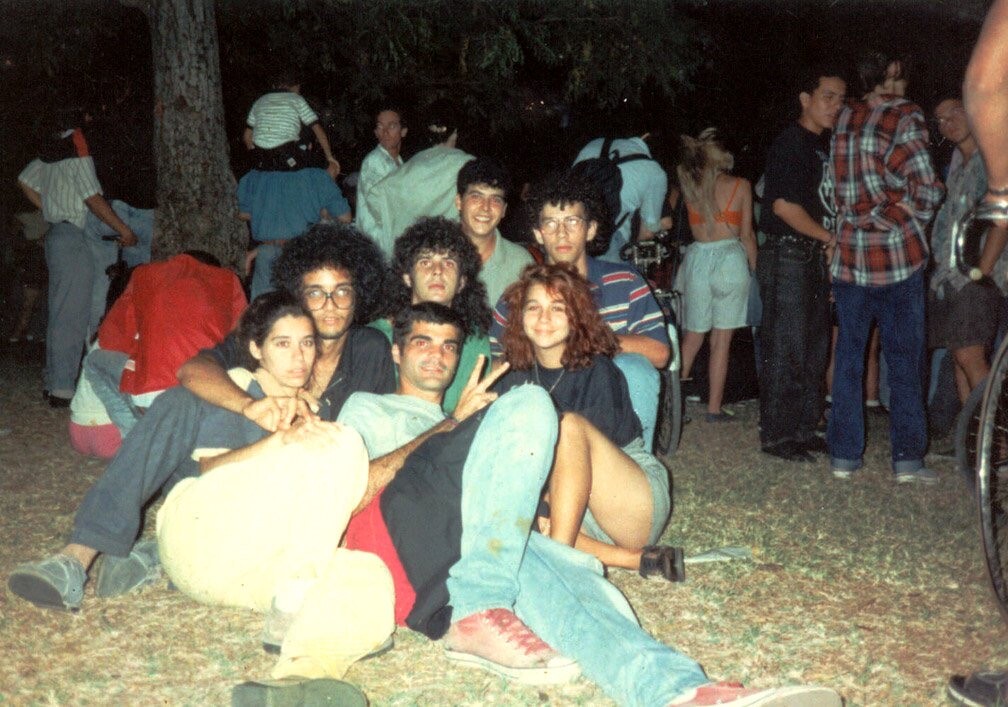

In front of the Havana capitol building, with my then-girlfriend and forever wife posing as peasants. Image courtesy of the author.

Cats because they were hunted and eaten. And fat people because they didn’t eat enough. All that remained of the obese of yesteryear were pictures in black and white, framed in living rooms alongside those who sat, unrecognizable, with their skin hanging off of their arms, evoking what they now viewed as their good times.

Not everything was about disappearances.

Some things actually appeared and others reappeared after not having been seen for a long time, almost all of them meant to substitute for the absence of food and transport. Or cigarettes and alcohol.

There’s nothing like a good crisis to turn alcohol into an essential item.

A good deal of the food, public transport, and alcohol substitutes were provided by the government itself to ease a crisis that it insisted on calling the Special Period.

Novelties such as:

–Soy picadillo

–(Hot) dogs without casing

–Goose paste

–Texturized picadillo

And, of course, bicycles.

The bicycles were not to be eaten. They were meant to substitute for public transport. The dogs, picadillo, and paste were equally unpalatable, but were aimed at substituting for food. (Don’t let yourself be fooled by names that had little to do with what they represented. Just as our stomachs were not fooled when they tried to process these dishes.)

The following also appeared:

–Rum in bulk

–Orange sparkling wine

–Yellows

–Camels

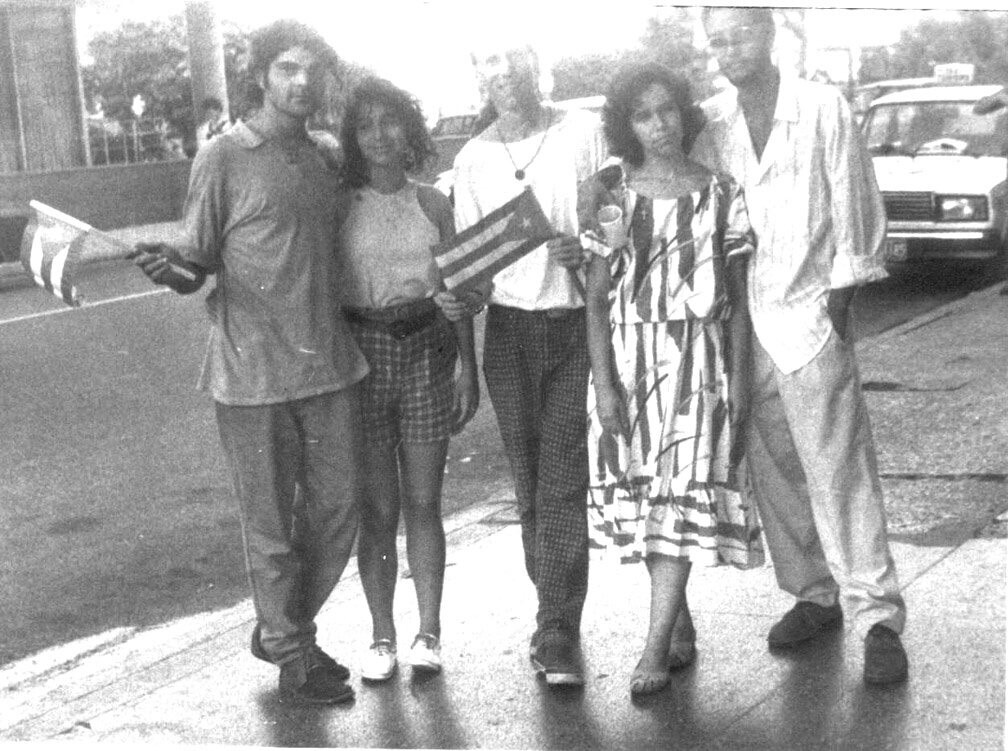

Commemorating the thirteenth anniversary of John Lennon’s death at Lennon Park, Havana, December 8, 1993. (It’s funny because at the time of Lennon’s death, his music was censored in Cuba, but years later Lennon homages became official.) Image courtesy of the author.

(Yellows were government employees who, posted at bus stops and strategic points around the cities and highways, were authorized to stop public or private vehicles and jam into them as many passengers as possible. Camels were enormous trucks poorly retrofitted for passenger transport, to the extent that the passengers came out transformed into something completely different. It’s no wonder that the camels were nicknamed “the Saturday night movie” due to the sex, violence, and adult language that took place on them.)

Between reappearances, there was an incredible uptick in the production of home-produced alcohols. And of the names to designate these: “train spark,” “tiger bone,” “time to sleep, my boy,” “man and earth,” “azuquín,” and others that were even more untranslatable into any known language.

Pigs became domestic animals: they would grow alongside the family and sleep in the bath tub to be devoured or sold as soon as they had gained sufficient weight.

If they weren’t stolen first.

Rarely-heard-of illnesses appeared, the natural offspring of poor nutrition. A result of poor hygiene and lack of vitamins.

(Because soaps and detergent—I forgot to say—were also among the first casualties.)

Illnesses that resulted in disabilities, blindness, or, if not treated in time, death.

Epidemics of polyneuritis, of optic neuropathy, of beriberi, of suicides.

Suicides not just of people. In those days, I recall seeing more dogs run over in the streets than ever and I supposed that they, too, tired of living. Or that the drivers tired of swerving around them.

Everything else was shrinking. The food rations that the government sold monthly, the hours of the day with electric power, the gas flame on the burner. Life.

The monthly ration of eggs was reduced to the extent that eggs ended up being nicknamed “cosmonauts” because of the countdown: “8, 7, 6, 5, 4.” I remember that at some point, the personal ration was reduced to just three eggs per month. After that, I don’t remember anything.

Bread also shrunk until it was nothing more than a portion that fit in the palm of your hand and, as a result of its obvious lack of basic ingredients, it turned out to be difficult to keep from crumbling between your fingers before you got home. (Paper bags had also disappeared and the plastic kind had always been a privilege reserved for foreigners, so the carriage of bread was inevitably done manually.) But not even the miserable and shrinking condition of those breads protected them against our hunger.

The struggle for our daily bread became a literal one: one day, while visiting the home of a fairly successful actor, I found myself in the crossfire between the actor and his teenaged son, whom the former was reprimanding, after the latter had consumed the bread belonging to them both, before trying to scarf down his mother’s piece.

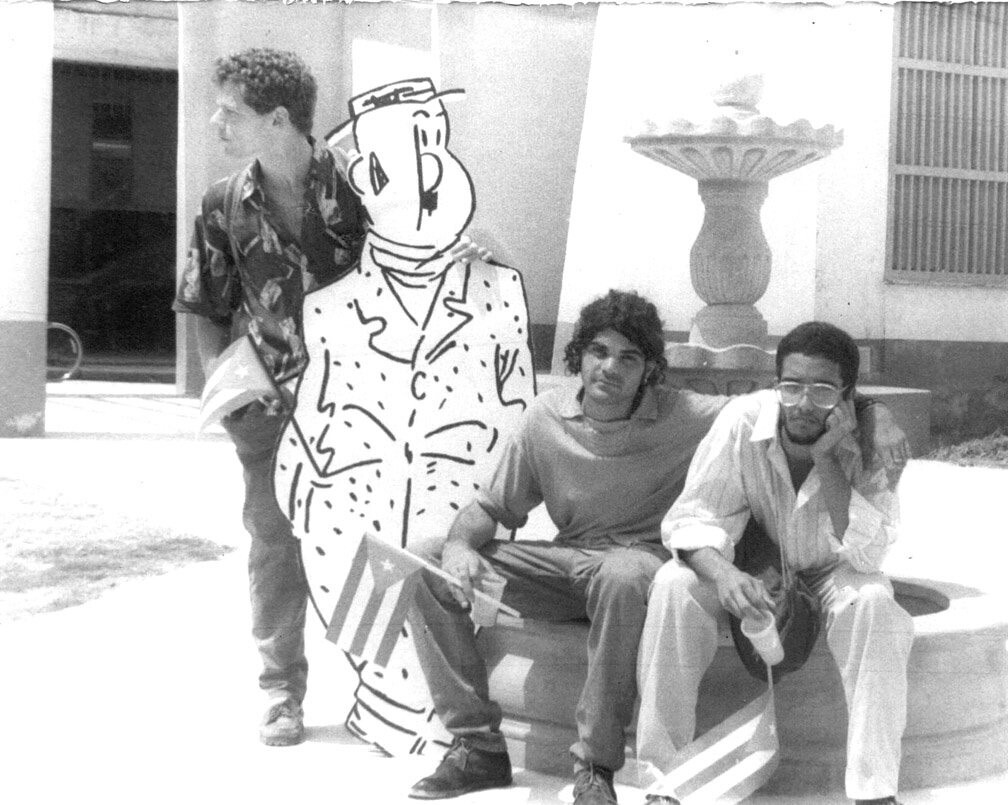

With the other curators of the exhibition “Del Bobo un pelo,” after being informed that the exhibition had been cancelled by the government, Old Havana, 1992. Image courtesy of the author.

The only thing that remained unchanged was official discourse. With “official discourse,” I am not referring to the “tendencies of elaboration of a message though expressive means and diverse strategies.” I’m talking about the more concrete definition of “a series of words or phrases employed to manifest what one is thinking or feeling.” Or, more precisely, what the country’s máximo líder thought and said, which was equivalent to what the country itself thought and said. Words and phrases that unfurled for hours in order to say the same thing over and over again: how willing we were to defend the conquests of the Revolution and how poorly it would go for us if it occurred to us to change our political regime Or how poorly it was going for the world when compared to us. Or how well we were doing if we compared ourselves with everyone else. I don’t remember them exactly nor do I have any desire to reread those speeches.

Said speeches also insisted on the irreversibility of our decision to build socialism, taken long before we had been born.

It was becoming clear to us that capitalism was built at the slightest neglect, while socialism required decades of incessant labor and we still couldn’t see whether we’d be able to put a roof on it.

Ours was open-air socialism.

Print media and television imitated official discourse in not letting on that there were any changes happening in our European sister socialist republics: the same triumphalist discourse about local advances in the building of socialism, the same quantities of overachievement, the same exuberant potato harvests that you couldn’t find anywhere later. That media did not outright announce the fall of the Berlin Wall. Or the execution of Nicolae Ceauşescu. Or the Tiananmen Square Massacre.

The events that were inconvenient to official discourse were either ignored or communicated in a way that differed as much with the reality as our homemade moonshine did with industrial alcoholic beverages.

In all those years, I did not hear the official media pronounce the word “hunger” except for in reference to another country. In those years, our misery did not receive any other name besides Special Period, a phenomenon that had its origins in “difficulties known to all.”

It was in those years that I was young, a recent graduate, happy.

I was lucky. Others were in the roles of mothers and fathers overwhelmed by the task of feeding their children without having any available food. Forced to make an omelet out of a solitary egg for four, five, ten people. Forced to prostitute themselves so their children could wear clothes. Forced to steal so their grandparents would not die of hunger.

Because there were those who died of hunger. Many. They were not reported as such. Somebody was reduced to nothing more than skin and bones and then a simple cold, a heart attack, a stroke finished him off. Or he committed suicide. Or he jumped on a balsa raft, which was another form of suicide. A hopeful suicide. Because if you got to Florida or some American boat picked you up along the way, you were saved. Back then, we called that “going to a better place.” Leaving the country, I mean. Traversing over ninety miles in those contraptions made of wood, nets, ropes, and truck tires across a rough sea, brimming with sharks, has always been something akin to a miracle. Even if we distribute the possibilities of death and escape evenly, it is a shuddersome prospect.

Later on in the day of the exhibition “Del Bobo un pelo.” On the other side of the little Cuban flags were printed the exhibition’s credits. Image courtesy of the author.

From 1990 to 1995, at least forty-five thousand Cubans arrived in the United States via balsa rafts.

You do the math.

And there are others, the ones who died in their homes of some illness that was hurried along by hunger.

Of those deaths, no one has reliable numbers. Nevertheless, this might give you an idea: in 1990, the average number of burials in Havana’s main cemetery fluctuated between forty and fifty daily. Forty on weekdays, fifty on Saturdays and Sundays. I know because I worked there. I left and when I returned, three years later, the sum had doubled: eighty burials from Monday to Friday and one hundred on weekends.

You do the math.

In the middle of that silent massacre, I treated myself to many luxuries. The luxury of going to the movies, of reading, of going to see friends and having them over, of continuing to write. The luxury of being haughtily irresponsible, of being happy in the midst of that atrocious hunger that invaded everything and made people pass out at bus stops or in the waiting room of any medical clinic.

That didn’t save me from going to bed hungry. Or from waking up hungry. From having a glass of powdered milk for breakfast and half of the infinitesimal piece of bread Cleo shared with me. From putting a bit of rice and soy picadillo or fish croquettes in a plastic container as my lunch (please don’t take the names we gave our meals too literally: we used them out of habit, so that we could deceive our hunger in the most effective way possible). Then, from biking over to the cemetery. Yes, throughout a large part of my last Cuban years, I pretended to be the historian for the city’s main cemetery. Fifty-five hectares covered in crosses and marble. Or, what amounts to the same thing: fifty-five hectares of hunger surrounded by hunger on all sides.

Because even in the very center of the city, in an area surrounded by lunch counters, restaurants, pizzerias, and ice cream shops, everything was closed due to a lack of food.

In times of absolute state control over the economy, the equation was simple: if the state didn’t have anything to sell, then there was nothing to buy.

And if they suddenly sold some cold cut with a dreadful appearance, you would have to spend three or four hours in line to buy it.

That was why I had to abide by whatever I carried in that little plastic container and wolf it down before the savage heat of the tropics turned it into a slimy, foul paste. Savor it down to the last crumb because there would be nothing else to eat until I returned home, at five in the afternoon, on my bicycle.

Or not. Because at home I wouldn’t find much, either. Rice, some vegetable, and later a brew of herbs yanked surreptitiously from the neighborhood’s flowerbeds to fool a hunger that was increasingly clever. I preferred for hunger to overtake me while I was out, watching some movie. Usually something I had already seen, at the Cinemateca, because the alleged new release movie houses projected the same films for months. At least at the Cinemateca, they showed one and sometimes two different films per day. I would meet up with Cleo there, when she got out of work, and my brother and his girlfriend or any of my friends would show up. In a city in which anything at all cost between twenty and fifty times what it used to be worth, at least a movie ticket remained the same price.

With my monthly salary, I could go to the movies two hundred times. Or buy myself two bars of soap.

It was rare for us to miss a concert, a play, or a ballet. There weren’t many artistic performances to attend: local singer-songwriters, Third World rock bands, European theater companies lost in some exchange program.

The empty, dark city, and there we were pedaling around. And praying for the “difficulties known to all” not to cancel that night’s event. To not return home with an empty stomach and equally voided spirit. Plowing through the dark, desolate city atop a bicycle, with a machete in hand so that anyone with the intention to attack us could see it.

Bicycles were like gold in those years. Like everything that could be used to move, get drunk, bathe, or fill a stomach.

The next day, the cycle would repeat itself: powdered milk, bicycle, rice, beans, movies, bicycle, rice, beans, and herbal brew.

A cycle accessible only to those of us who had the privilege of not having to support a family, a household. The luck of not being forced to take life seriously.

Between that October in which I invited my parents to eat at their favorite restaurant and the other October in which I finally left Cuba, five years passed. A horrific, interminable quinquennium.

And a happy one, because I had the good fortune of being young, irresponsible, and in good company.

But, as far as I can remember, not a single time in those five years did I again think of the record player. The record player I had not been able to buy myself because the country that produced it had disappeared along with our lives of yesteryear.

Disappeared for good and for worse.

Now, at last, in the middle of hipsters going gaga over vinyl records, I’ve bought myself a small record player. A pretext for gathering, in no hurry, but steadily, the record collection I never had.

Let others search for an authenticity in those records that is unknown in the digital world: for me, that turntable has the sweet, cold taste of revenge.1

GDR turntable. Image courtesy of the author.

Recipe: Rooster Stew

No recipe came to the rescue more often in the Cuba of my younger years than so-called “rooster stew.” The previous sentence requires two clarifications. First: the Cuba of my younger years coincides with the era that the Cuban regime, with its fertile imagination for naming reality, called the Special Period. “Especially miserable” is what they meant, but they didn’t say so out of modesty. That creative Cuban penchant for dubbing the universe leads me to the second clarification. And it is that so-called rooster stew is nothing more than a mixture of water and sugar. The bit about “rooster” is purely metaphorical and there was not a single thing in the rooster stew that evoked stew except for its watery consistency. I don’t know if the name was invented at that time or if it was an old popular expression brought back into service. What I do know is that in the 1990s, the state’s lunch counters (the only ones in existence by then) advertised water with sugar as “rooster stew” on their menus. Often, it was the only thing they had to offer. Or they presented it as the main entrée along with a dessert that usually consisted of sweetened grapefruit peels.

“Rooster stew” was not the only name for that combination of water and sugar. It was also called “prisms.” In this case, I can explain the origins. It comes from a television program with that name, Prisms. It came on around 11:30 pm and was advertised with the tagline, “Just before midnight … Prisms is for you.” That was at roughly the same time water with sugar was needed most to calm hunger pangs and allow us to go to bed with something in our stomachs. “Milordo” was another appellation this mixture of water and sugar received, but I do not know the etymology. As they say about the Inuit and snow, we Cubans had an abundance of names for sugar dissolved in water. Sugar was still our country’s main industry and, within the strictest rationing constraints we had to survive, the sugar quota was particularly generous: five pounds per person per month. Water was not exactly plentiful, but at least there was enough to prepare said dish.

Ingredients:

–water

–sugar

Directions:

Fill any container with water. It can be cold, hot, or room temperature, that’s how adaptable this recipe is to individual tastes. Then add as many spoonfuls of sugar as you like. Stir the mixture vigorously with a spoon. That’s it.

You can serve the rooster stew immediately or, if you prefer, refrigerate before serving. Don’t take the recipe’s name to heart. There is no need to serve it in a bowl or to eat it with a spoon. A glass will suffice.

Note:

After drinking it for a few days, the taste of rooster stew becomes monotonous. In this case, I recommend that, prior to adding the sugar, you boil the water with some aromatic herbs. You might say that in the places where rooster stew is an acceptable dish, aromatic herbs aren’t abundant, and you would be right. As such, when the time came for me to prepare my rooster stew, I would go wander around my neighbors’ gardens and steal some sprigs of balm mint or lemongrass. This made the nighttime consumption of rooster stew a perfect compliment to the task of eluding any surveillance the neighbors could exercise over their gardens. I never thought of naming this variation, but it could well be “rooster stew aux fines herbes.” If the word can’t lend a certain grace to the matter, then how to justify its existence?

Excerpted from Enrique Del Risco, Nuestra Hambre en la Habana: Memorias del Período Especial en la Cuba de los 90 (Plataforma Editorial, 2022).

Subject

Translated from the Spanish by Anna Kushner.