The Many Faces of Bread

There are three things that have long fascinated me about bread. Firstly: it is everywhere. Every place, every culture has its own bread, whether made from barley, rice, corn, spelt, rye, or teff, fermented or not, flat or leavened, brown, yellow, or white, often round, fried, boiled, or cooked in all kinds of ovens. Some breads taste slightly of ashes or oil, while others can be acidic or sweet. Sometimes bread is more than just the combination of flour and water; it might have sourdough, salt, sugar, or seeds. It has many names: chapati, injera, pita, tortilla, baozi, ugali, and many more. Many Western bread-lovers might contend that some of these examples shouldn’t even be called “bread,” but I take a more expansive view. For me, bread is what daily human meals have centered around since the species started to harvest cereals, the food that we carried with us when we were nomadic because it lasts for many weeks in a bundle.1

The second thing that comes to my mind when I think of bread is “company.” Con-panis. With-bread. In its older usage, the word draws from companio in Latin, literally “one who eats bread with you.”2 If bread is essential to what humans eat, it thus sits at the center of social interactions. When we share it, with humans and nonhumans alike (think of your dog, or ducks at the park), it signals love, bonding, companionship. Making and eating bread is a collective human experience.

Lastly is the role that bread has played in social and political change. In Ancient Rome, emperors used panem et cicenses (bread and games) to keep the people happy and disciplined. Historically, so long as the otherwise exploited could put bread on the table, relative stability was ensured. But once the price of cereals rose, many took to the streets. This has of course continued to play out in more recent history. Examples include the Flour War (April–May 1775) in the lead-up to the French Revolution,3 revolts across the entire Italian Peninsula following the 1869 grist (ground grain) tax,4 or the post-2008 spike in grain prices at the dawn of the Arab Spring,5 just to name a few. The increasing frequency of bread riots since the 1970s (Egypt in 1977, Tunisia in 1983–84, and Jordan in 1996) reveals the destruction to the global food system brought about by structural adjustment programs designed by the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF). In short, bread leads to revolution. There is much to be said about that historical correlation, but personally I’m more fascinated by the courage of people who defend their access to a good loaf. Because, as far as I’m concerned, access to a good loaf is essential to human dignity.

The Many Deaths of Artisanal Bread

I started making bread at home when my home was no longer France, in places where bakeries were overpriced and not that good. Later, when I lived at a squatted farm in Tuscany, I began to bake artisanal bread to sell at markets of local producers. This is when I learned that sourdough is not all that complicated and that its active cultures—living beings—are what make it so alluring. I’ve slowly tamed bread and it’s slowly taming me, just like Le Petit Prince tames the fox and vice versa: fully respecting what the other is, bonding anytime our paths cross, embracing the fact that neither of us will own the other. It’s been a journey that has taken me across France to make, talk, and dream bread with many people. Observing the French and wider European contexts, I’ve found that the politics of bread is a proxy for talking about the broader dynamics and deficiencies of the current international food system.

Though the milling industry had already become big and powerful by then, after WWII in France (and elsewhere in Europe) the various links in the industrial chain came together to form a giant bread business. Along with implementing land reforms, the French state slowly limited the wide variety of available wheats to a selection of “modern” ones; the only varieties to be sold after 1949 were more resistant to lodging6 and guaranteed high yields when spayed with the right pesticides and fertilizers. Modern wheats were also selected for their baking strength. The higher the strength, the more resistant the gluten is when it comes into contact with water, and thus the easier it is to make leavened bread.7 Since kneading had come to be done by big machines instead of human hands, high baking strength was necessary for producing loaves attractive to consumers. But this came at a nutritional cost: bread rich in heavy indigestible gluten is one of the reasons for the development of ubiquitous gluten intolerance today.8

In the 1950s, French wheat fields expanded in size to produce the right raw materials for this new milling industry. In the mills, flours were (and still are) mixed and refined on a continuum from white to whole wheat, depending on the amount of bran left in the flour. The less bran, the poorer the flour is in fiber and minerals.9 To compensate for the nutritional loss from the chemically induced whitening process, the milling industry started to enrich flours with nutritional supplements and all sort of “delicious,” “healthy,” chemically produced processing aids, which would become standard.10 In fact, when bread first became a commodity, white bread was always trendier than browner bread.11 It’s a class thing: historically, white bread was traditionally for rich people because it was thought to demonstrate the “cleanliness” and “purity” of the flour.12 This fallacy was reproduced with industrial bread production, and so shitty industrial white flour started to flood the market.

After the milling industry came the baking industry. In the postwar period, bread-making companies began to use a wide array of baking improvers while also over-kneading the dough to oxidize it so it would whiten further. In this situation, bread-making no longer depends on its environment: in dry or humid weather the recipe remains unchanged. Bread is no longer alive; it has become a machine, just like the baker.13 In bread factories, flours only need two hours to become bread, rather than the typical twenty-four. Like most of the food we consume in the West, bread became rationalized. And hyper-leavened, innutritious, high-glycemic-index white bread took over supermarket shelves. Efficiency above all else, at the cost of quality, respect, and pleasure.

The bread industry could have continued in this direction and thrived. Instead, in a quintessential neoliberal move, it co-opted a smaller “mom-and-pop” industry, adding a new link to its corporate chain. It all began in 1998 when the French government passed the May 25 Law, probably under pressure from small bakers afraid of disappearing due to supermarket competition. The law established a strict definition for what it means to be an “artisan” baker. To claim this title, bakers have to perform the entire bread-making process from kneading to baking, using selected raw materials, at a brick and mortar establishment, and without in-process freezing. While the rest of Europe saw many of its traditional bakeries close in the face of aggressive supermarket chains, France sought to save its bakers, while also using the romantic image of the baguette (especially paired with French cheese and wine) to attract mass tourism. The campaign was successful on its surface, as 95 percent of French consumers now buy their bread from artisanal bakeries.14

This would be a beautiful story about successful state intervention if, twenty-five years later, I could go the artisanal bakery around the corner and eat delicious, healthy bread. But, as is often the case with state intervention, the public was misled—including at least one disillusioned Australian blogger living in France.15 The story of institutionalizing “artisan” bread production in France is really the story of corporate recuperation and consolidation. The food-processing giant Vivescia (3.1 billion euros total revenue in 2021) now controls much of the artisan-bread value chain; it owns the second largest grain cooperative in Europe, and its brand Francine is a huge player in the milling industry (covering 32 percent of all-purpose flour market in France in 2018). Since the May 25 Law, Vivescia has also absorbed fifteen thousand artisanal bakeries into its affiliate chain Campaillette, forcing subsidiaries to follow standardized recipes and to use Vivescia-produced ingredients, turning bakers into mere machines. In 2015, an amendment to the 1998 law guaranteed the production of unhealthy bread in artisanal bakeries by introducing the requirement that artisan bakers hold a special degree (Certificat d’Aptitute Profesionnelle, or CAP). This new requirement systematizes the learning of “traditional” bread making recipes that rely exclusively on chemical yeast and near-white flours. As a result, many artisan bakers wake up in the middle of the night to combine water and ready-made mixes, breathing in industrial flour and baking improvers that trigger asthma and pollute their lungs16—all to make second-rate bread that does nothing for the health of those who eat it.

Now there is a new player in the “artisan” bread game. Let’s call it the “bobo” (bourgeois bohemian) baker: typically a former white-collar worker who left the corporate world in search of more meaningful work. Bobo bakers are behind the growth in organic sourdough bakeries. They are fond of greening capitalism but are sometimes blind to class and social struggle—which is one reason why they can sell a one-kilogram loaf for as much as fourteen euros in Paris. It is good bread made with good flour, and it tastes great if you can afford it. (Admittedly, this picture is a bit exaggerated—I unashamedly hold the greenwashed capitalist system responsible for this situation, not the workers who comprise it, save for a few.) Some of these bobo bakers have themselves been exploited my even more aggressive and cynical bread entrepreneurs. Thomas Teffri-Chambelland is a major French bread star, praised for his skillfully marketed approach to sourdough bread. Knowing that some deserting white-collar workers are more than happy to spend a lot of money to make their bakery dreams come true, he opened the private École Internationale de Boulangerie to train future top bobo bread bakers, charging “only” fourteen thousand euros for a four-month course.

Another lucrative branch of “eat-healthy” capitalism is the gluten-free bread industry. What’s ironic about the gluten-free market is that it offers a solution to a problem created by food industrialization in the first place. As mentioned earlier, it is precisely the over-consumption of industrial bread (and other industrial products) that has created a huge population of people who are unable to digest it.

Bread Strikes Back

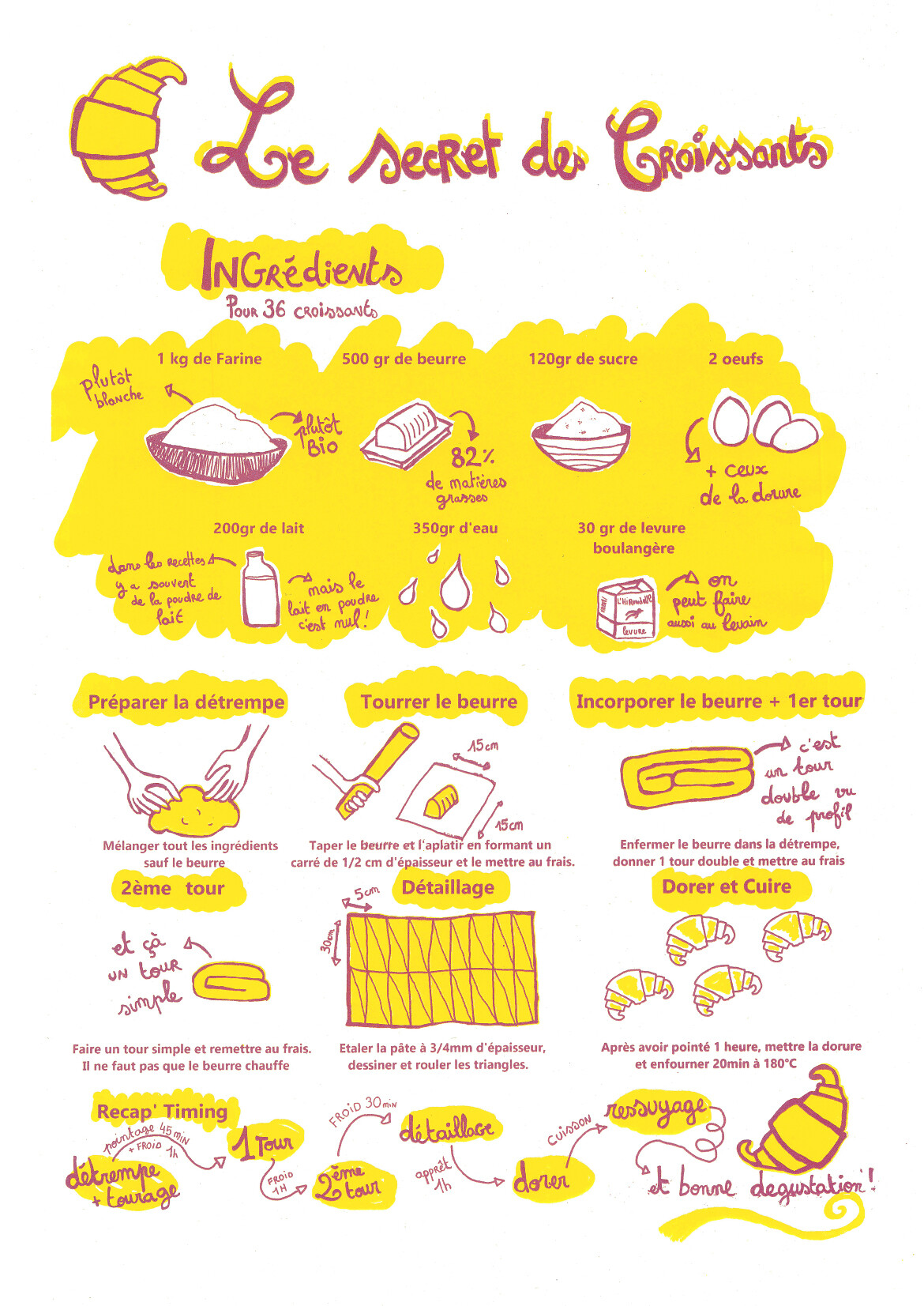

If you love bread but hate agribusiness and monoculturization, what are you to do? I started to find answers to this question when I got involved a year ago with a Francophone bakers’ network called the Internationale Boulangère Mobilisée (Mobilized Bakers’ International, IBM). It is not a collective; it does not have a common charter. I can only speak about my own understanding of us because this “us” is still in the making. IBM is composed of whoever wants to join—from those who bake at home, to mobile bakers with DIY wood-fired ovens, to semi-large-scale paysannes-boulangères (peasant bakers) who make bread from wheat they grow themselves and legally sell it. IBM gathers around an idea of bread made with sourdough and peasant-wheat flour,17 by hand or with the help of small machines, baked in wood-fired ovens when possible (though we are looking for more ecologically friendly alternatives). We all believe that bread is political, though we may not all agree on the exact political form it takes. We all try to integrate bread into our lifestyle, work, and relationships, if in different ways. At its most basic IBM is a mailing list with about 250 subscribers, where we ask each other for help and share ideas. We sometimes meet in person for a couple of days in various places in France, to make bread or croissants together, exchange recipes, invite townspeople for pizza and performances, learn to weld or build a wood-fired oven, talk and write about bread politics, and build friendships and solidarity. IBM also runs the École Boulangère Mobilisée, a self-managed school for those who wish to pass the CAP test to be an artisan baker in France without following the conventional curriculum.

In IBM, I have found the energy to expand the political horizons of my bread quest, because I am no longer alone. I have found a network of companions and deep relationships—friends to call and visit and make bread with. I have grown hopeful that the seemingly little things we do can become powerful when done together. I have learned that anyone anywhere can make good bread, for everyone and not just for those who can pay. I have realized that a political loaf always tastes good, always fills the stomach with good stuff, even if it sometimes looks flat or lacks the sheen of supermarket bread. This is not because breadmaking, collective or otherwise, is by itself going to change the contemporary food system, but because together we have the power to create imaginaries of work and relationships that do not conform to the dominant paradigm of production.

Recipe courtesy of Bertille Gatteau, 2022.

For most of this article, I will talk about bread common in the West: leavened bread, made mostly of wheat flour, that is said to have appeared in Ancient Egypt four millennia or so ago—even though some women somewhere earlier had surely experienced the chemical reaction of flour and water giving birth to yeasts and bacteria. See Ali Rebeihi, “Les plaisirs et bienfaits du pain,” April 7, 2022, France Inter, podcast →.

See →.

The title of this text is taken from Louis Blanc’s History of the French Revolution, where he recounts the victory cry sung by people who captured the King, Queen, and their child: “We will lack bread no longer! We have brought back the baker (masculine), the baker (feminine), and the little baker.” See →.

See Association Terracanto, “Le chant des grenouilles—1 chapitre,” June 24, 2020, Chant de la multitude, podcast →.

See Rami Zurayk, “Use Your Loaf: Why Food Prices Were Crucial in the Arab Spring,” The Guardian, July 16, 2011 →.

Lodging occurs when a vertically growing plant falls over, damaging the potential for growth. See →.

For more details, see →.

See Groupe Blé de l’ARDEAR AURA with Mathieu Brier, Notre pain est politique (Dernière Lettre Eds, 2019).

But bran also provides shelter for most of the pesticides and chemical inputs. Be wary of nonorganic whole wheat flour!

It’s like any current food-processing method: the raw material is not used for its content, but for its role as pure matter. The industry needs wheat to turn into flour, but the process empties the wheat of its substance, so new substances need to be added. The same goes for cheap wine: harvested grapes can be green or moldy—it doesn’t matter because the taste will be created chemically. As part of the current fad for healthy living, one finds many articles describing white flour processing and its consequences.

This trend has now completely reversed: a browner color now means healthy, more expensive bread.

Until the nineteenth century it was not uncommon for millers, retailers, or small merchants to add ashes or tiny rocks to flour, so it could be sold at a higher price.

Paraphrased from an artisan baker interviewed by Ali Rebeihi, “Les plaisirs et bienfaits du pain.”

See →.

Wendy Hollands, “Artisan vs. Industrial Bakeries,” Le Franco Phoney (blog), February 9, 2014 →.

See →.

There is an quasi-political distinction between ancient wheat (blé ancien), which is most commonly used, and peasant wheat (blé paysan). The former implies a return to tradition, to a kind of lost Eden that never existed, and does not acknowledge the interaction between seeds and the peasants that sow and mix them, between seeds and the environment they naturally evolve in and with.