The Museum of the Federation of Trade Unions of Belarus, Minsk.

It’s a Queer Time

Since the very first day of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the Belarusian state has surrendered its territories and infrastructures to the Russian army. In allowing Russia’s troops to use roads and railways, military bases, airports, hospitals, and so on, Belarus has become a co-aggressor in the military invasion of Ukraine. This was made possible by the past two full years (and many more prior) of police and state violence. Together, these forces have effectively suppressed solidarity networks, independent journalism, and strike movements inside of Belarus. At the same time, protest movements in Belarus since 2020 have developed significant methods of struggle that are focused on creating solidarity networks as well as destroying infrastructures and logistics of power. What kind of resonances are evolving between these coexistent realities?

In recent years, something has been visibly growing in Belarus: an event, a process, an infrastructure, a revolution, a break. How to define the spatial and temporal qualities of this event? What is the beginning of the event, and how can anyone foresee its ending? What makes the event possible and what constitutes it?

I began working through these questions before the current war. And now the war proposes a solid temporality of emergency—the only temporality, at least for now. Being caught on both sides of this time line reminds me of the first pages of Elisabeth Freeman’s Time Bind: Queer Temporalities, Queer Histories. The book opens with Robert Graves’s World War I poem “It’s A Queer Time,” which briefly chronicles the maddening quickness of a soldier’s unwanted wartime jumps across time, location, memory, and reality: “It’s hard to know if you’re alive or dead / When steel and fire go roaring through your head …”

In his book on the theory of the event, Slavoj Žižek concisely defines the notion of the event as an “effect that seems to exceed its causes. The space of an event,” he says, “is that which opens up by the gap that separates an effect from its causes.”1 At the same time, Žižek dismisses the possibility of the Belarusian protests constituting such an event. In an article for the Independent titled “Belarus’s Problems Won’t Vanish When Lukashenko Goes—Victory for Democracy Also Comes at a Price,” he writes: “The ongoing protests in Belarus are catch-up protests, the aim of which is to align the country with Western liberal-capitalist values.”2 By limiting the temporality of these protests to an attempt at “catching-up” with Western time, Žižek deprives Belarusian protesters of agency and implies a faulty alliance with neoliberalism. On the contrary, I would claim that the prefigurative forms of political organizing seen in recent protests here actually illuminate the future—not only the future of a single country, but also that of a much broader geopolitical area. With the war in Ukraine, this light actually becomes more visible.

Prefiguration and the Queer Temporalities of Post-socialisms

Thinkers like Neda Atanasoski and Kalindi Vora propose that post-socialist temporality is a queer one; in other words, it implies different relations with the historical past and unexpected connections that resist linear and teleological concepts of time.3 Displaced from specific geographies that exceed Soviet state socialism, queering post-socialism underscores turbulences and continuities of time, as well as proximate causations of those turbulences and continuities across the region. Queer temporality resists so-called “straight time,” defying neoliberal reproduction and “destabilizing and rupturing the very logic of linearity.”4 There is no development from the primitive to the complex; instead, progressive tendencies can be discovered in a variety of times. The queerness of post-socialism also amounts to a refusal to synchronize with Western (or Russian) neoliberal development.

Throughout the Belarusian uprisings in 2020–21, three post-socialist museums in Minsk, each a seemingly stable reservoir of time, were further disturbed by protest temporalities. Some of them even appeared at the center of symbolic struggle. Museum spaces tend to control the master narratives of history through specific chronopolitics. By further examining the closed off and garishly visible exhibitions of the Museum of the Workers Movement, the Museum of Stones, and the Museum of the Great Patriotic War, what queer temporalities of post-socialisms can be liberated under the present constrictions, and what prefigurative political and art practices might still inform possible futures? Here I specifically mean futures that are simultaneously more critical and more affirming of their legacies of socialisms, and that could therefore undermine both Western and Russian imperialist and capitalist models.

Feminist scholars Nadzeya Husakouskaya and Alena Minchenia wrote in a 2020 essay that “the bonds and networks [created during the Belarusian protests], this new sense of meaningfulness—as well as a shared experience of living through grief and pain—cannot be undone in Belarus.”5 And indeed, in the present war, previous networks of militant organizing, agitation, and solidarity have already been redirected toward anti-war resistance, transgressing the newly drawn national borders of Belarus.

Artist and researcher Olia Sosnovskaya proposes several frameworks for thinking and writing about the protests in Belarus, which have not yet ended. She describes the temporal paradox of protests as the “future perfect continuous,” borrowing the grammatical tense in English that outlines an action that began in the past, takes place in the present, and will continue in the future. “By moving, mourning, organizing, exhausting, refusing, celebrating together,” she writes, “we simultaneously rehearse and exercise the future.”6 A long time span allows activist and artistic initiatives to not think of the future as a utopian horizon just out of reach, but rather to actively practice this temporality at any given moment in time.

According to cultural theorist and practitioner Valeria Graziano, prefiguration or prefigurative politics describes situations in which the organizing principles behind social movements, including their political agency and reproduction, are analogous to the political goals the movements want to achieve.7 Prefiguration further proposes thinking of the event not as part of a linear or goal-based strategy, but rather a performative possibility that materializes the future and utopian impulse at the moment of protest. Thus, protest becomes not so much an event, an insight, or a rupture, but an infrastructure that can generate new forms of social organization: situational models of society, forms of cooperation and solidarity.

The Museum’s Unsettled Past

The insurrectionary events in Belarus have significantly influenced how museums function with regard to state instrumentalization of memory, the signification of anti-fascist struggles, and politics in general. Considering that uprisings in Eastern Europe and particularly in Belarus have long defined post-socialist temporality, it is important to trace how they are represented in museums’ ever-changing narratives of history, and how museums operate in moments of political crisis.

Seemingly, the post-socialist museum is a space that stubbornly attempts to resist various gestures toward destabilizing connections between the past, present, and future. Many try to mask various paradoxical relations, ruptures, and time line turbulences inherent to the histories, documents, thoughts, and actions behind the objects they exhibit. The perplexity and oddity of state museum displays illustrate a certain frustrated attempt at cementing post-socialist temporality into linear chronology. In describing prototypical communist museums—the Lenin Museum and the Museum of Revolution in Moscow—historian Stephen M. Norris speaks of hegemonic models that have created ideological stability and a version of the “settled past.”8 These projects are state campaigns that model a reliable historical time line synchronized with Marxist-Leninist ideology and its projected aspirations for future generations.9 To use Michael Bernhard and Jan Kubik’s term, such museums can be seen as “mnemonic actors”—“political forces that are interested in a specific interpretation of the past.” And the networks in which these museums are located may in turn be “mnemonic regimes,” reflecting “the dominant pattern of memory politics that exists in a given society in a given moment.”10

Naturally, at major museums, the political reappropriation of history follows a regime change. But what happens in museums on the margins, whose walls reflect change at a much slower pace? What happens to displays that for various reasons, chiefly economic, cannot illustrate societal shifts as they happen? If so-called museums of communism became a crooked reflection of communist museums, is it possible to better outline the intervening temporal complexities, perplexities, time gaps, and slips through the notion of the post-socialist museum? In such spaces, the past could not be made stable or fixed. Instead, it became unsettled.

Post-socialist museums cannot fix the past, and cannot be embedded in logics of linear display. After all, post-socialist temporality is fragmented, destabilized, and queer. Historian and researcher Iryna Sklokina registers this in the development of Ukrainian museums in post-Soviet time: On the one hand, so-called people’s museums, or local history museums, invited the local population into the process of collectively constructing local memory. On the other hand, museums would not be subjected to a singular, officially sanctioned thematic exhibition plan, and therefore would not always “embody a totalizing overarching narrative.”11 Curator Natasha Chichasova makes similar claims about a time paradox inherent to post-socialist museums: “The situation of the museum … seems to be a stalemate: the unproductiveness and redundancy of the museum turn it into ballast, where the old has become obsolete and requires new investments for reassembly, and the new still does not materialize.”12

What can a close look into three museum spaces tell us about the queer nature of post-socialist time, as well as about cemented or emancipated time?

1. The Museum of the Workers Movement: General Strike

In October 2020, a group of friends and I tried to get into the Museum of the Federation of Trade Unions of Belarus (also known as the Museum of the Workers Movement). The museum is located inside the Palace of Trade Unions, a prominent building on one of Minsk’s main squares. Operated by trade union officials, it remains largely unknown and inaccessible to the general public. First we tried to enter the museum directly from the street, and later had fruitless correspondence with a trade union representative. The administrator of the museum (perhaps the only worker there) claimed that Palace management, a separate entity, was responsible for granting admission—and only, she added, to organized groups. After a series of long conversations, she stopped picking up the phone.

My mother, the former deputy chairwoman of the trade union committee, learned in a subsequent phone call that the museum simply does not want to take groups “from the outside.” Though we know it exists, we were never able to see the history of Belarusian union and labor movements narrated in this palace hall.

As it turned out, the evening after our last attempt to enter the museum, the head of the Trade Union Federation was organizing Lukashenko’s biggest rally after two and a half months of mass protest. The rally was to take place on October 25, the same date that opposition leader Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya had set as the “people’s ultimatum”: Lukashenko’s resignation, or a general strike. On October 26, the latter was announced. Its stated objective was to dismiss the illegitimate government, to free political prisoners, and to stop police and state violence. The staff at the Museum of the Workers Movement was probably afraid of civil disobedience.

We can only see this museum through the few poor-quality photographs available on the internet. Several days earlier, we had also tried to enter factory museums in Zhodino and in Soligorsk, two cities that have large-scale industries and therefore rather strong workers movements. We were denied entry to these museums too. They are protected by security; you cannot spontaneously visit them. Not only was the representation of production hidden from us, but also the history of the struggle. The official displays of ceremonial history that we could see from behind the buildings’ front doors—awards, gifts, and portraits—served to hide existing faults, experiences, and evidence of worker organization.

We thought such museums would present the history of socialism, the story of the poor and hungry, of those working for pleasure and giving up work, striking and standing in solidarity, doing invisible work, hating power, and comrades offering one another a helping hand. What could the objects and documents in these workers’ museums tell us? What would the wall text and tour guide’s narrative present to us? Perhaps some objects would be critical of the factories’ directorship, of capitalists, and the exploitation of labor. They would be displays of solidarity and could continue to make alliances with contemporary workers and other material bodies. The museum objects would be comrades who had won back their time. The museum itself would compel us, following Saidiya Hartman, to “critically fabulate” local stories of struggle:13 for example, the story of female smugglers in Rakov who organized illegal border crossings during World War 1, or the story of Lake Narach fishermen who went on strike to defend their right to fish when Polish scarcity policies went into effect in 1935.

As mentioned earlier, our visit to the Museum of the Workers Movement correlated with the call for a general strike. Earlier, in August 2020, a prior strike was among the most immediate and powerful responses to mounting police violence under Lukashenko’s regime. Along with industrial giants like fertilizer manufacturers Belaruskali and Grodno Azot, whose workers have active strike committees, state cultural institutions went on strike as well: the Belarus State Philharmonic, Yanka Kupala National Theater, and the Mahilow Historical Museum, among many others. Cultural workers employed various forms of labor unrest: they picketed outside of non-striking institutions, gave concerts that disrupted “regular” music and theater performances, published statements in support of the opposition movement, and withdrew from events.

Taken together, these and other forms of protests used the logic of acceleration and escalation to push a political agenda and also to make their own time lines. For example, different and overlapping groups marched almost every day between September and October 2020: pensioners on Mondays, disability rights activists on Thursdays, women on Saturdays, and so on. The most vibrant protest column was comprised of LGBTQ+ activists. This group often joined the womens‘ marches as well. In producing powerful critiques of the sexist, patriarchal structures underlying the ruling regime, the queer column generated performative gestures and imagery that directly challenged the violent imposition of “straight time” also known as state policing. These daily protests would culminate in a general march each Sunday. Even if Tsikhanouskaya’s call for a general strike was not ultimately “successful,” it did generate its own temporality. This, in turn, created a distinct mode of pressure on the government. As many activists and commentators have said over the years, the role of street politics is to provoke and to escalate. In this case, the state was moved to react in a similar but different spiral of escalation—with violence and repression.

The multiplicity of protests, each with its own mode and its own way of (re)shaping time, also placed the traditionally linear logic of political action into question. Information Stands, a work by the artist group Problem Collective, touches on the diversity of strike tactics while questioning the history and representation of strikes in Belarus. The group designed and publicly displayed several boards focused on thematic topics like strike, nature, and the commons; strike, care, and reproductive labor; strike and reading; and so on. This work and the evolving, cross-temporal realities it represents resonate with what Gerald Raunig calls the “molecular strike,” a “reorganization of time and new time relations that implies manifold simultaneity of speeds, slow movement, standstill, and acceleration.”14

2. Museum of Stones: Infrastructures of the Event

Besides the performance of bodies in public space, an underlying material infrastructure of protest networks makes the political (re)organization of time and space possible. In Belarus, thousands of people were mobilized in the decentralized networks of Telegram chats (and other digital platforms), channels without any clear leadership. As my comrades in the artistic group eeefff have noted, this formed the foundation for “algorithmic solidarity.”

One winter day in 2021, I received a forwarded message on Telegram. It was a link to a chatbot channel called “The Museum of Stones.” The bot invited me to read a newspaper of the same title, and announced that it would begin sending me randomly selected editions of the PDF-based protest publication. By that point in time, most of the independent print newspapers in Belarus had been shut down, and extremists had claimed most independent online platforms. During the first days of protest, the internet was shut down entirely. The Museum of Stones, distributed online as a ready-to-print, black-and-white A4 booklet, was one of many similar outlets that carried the potential to bring information to people who had no internet. It also allowed people with access to a printer to distribute and agitate in their own districts and places of work. The authorship is usually anonymous, and editions of the paper are distributed through already existing Telegram channels.

The Museum of Stones newspaper seemingly borrows its name from an open-air museum in the sleepy suburban district of Uručča. The original Museum of Stones was constructed by scientists from the Institute of Geochemistry and Geophysics at the National Academy of Sciences, whose laboratories were based in the same location in the outskirts of Minsk. The museum is divided into several landscape galleries featuring a selection of around 2500 stones, rocks, and concretions—magmatic, boulder, and metamorphic forms collected from the territories of Belarus in the late 1980s that represent a geological map of Belarus at scale.

What is the connection between these prehistoric stones that a glacier brought to the country (in the temporality of deep time) and the perturbations of post-socialist immediacy? Some nearby Academy of Sciences facilities were neglected in the 2000s and used to play host to raves. Since 2005, these facilities have been partly redeveloped into a Hi-Tech Park (HTP). HTP was a state project that generated tax revenue and a legal structure for the development of IT technologies in Belarus. Initially based on the idea of outsourcing highly professionalized IT labor to a much cheaper workforce in Belarus, it became a cluster of several hundred companies operating extraterritorially and performing research on AI, software, gaming, and apps for the health and finance sectors, including cryptocurrency and blockchain research. Various companies with headquarters in the Park are exempt from most taxes, including income tax. HTP has been promoted as an Eastern European Silicon Valley. At the same time, it also remains under strict ideological control and its administration is subordinated to the president of the Republic of Belarus.

As the protests in Belarus are built on a strong digital infrastructure that has helped to provide alternative means to count votes, organize agitation, crowdfund, provide anonymous means of communication, and create digital solidarity platforms, it is no surprise that many IT workers have joined the protest movement. Some specific examples of this intersection include chatbots made by Rabochy Ruch (Workers Movement) and BYPOL (an association of former police officers in exile), as well as the Movement of the Many’s chatbot, which generates militant and sometimes playful suggestions for action. Between discussing various ways of striking within the IT industry, developing digital solutions, and protesting in front of the HTP, many workers and entire companies have withdrawn their participation in the HTP for political reasons.

So, it is hardly surprising that newspapers like The Museum of Stones, among others, were developed with the technical support of IT workers. Editorially speaking, The Museum of Stones newspaper has also featured a selection of anonymous materials on technology, partisanship, self-organization, and so on. One of these articles promotes the idea of a “cybernetics of the poor” as an answer to the existing “high tech and complexly-organized police cybernetics of a thousand eyes.”15 Other articles include guides for political self-organization, how to survive prison detention, combatting conspiracy theories, the use of AI and low-tech technologies, as well as maps of the area that connect the Museum of Stones, HTP, and scientific facilities with underground parties and anarcho-punk concerts held in post-Soviet ruins. It features interviews with militants, anarchists, and queers. The design itself connects the monumental force of deep-time stones with low-key, post-internet graphics.

A similar nexus of artistic, IT, and political strategies is also reflected in the work of the artist group eeefff. In their work Tactical Forgetting, they appropriate memory-training software to explore strategic modes of disremembering. The artists uploaded various materials to a machine-learning interface, including documents, media, and communication related to the strike movement in Belarus; video of a visit to a paramilitary computer game developer; footage of suspended construction sites in Minsk; and traces of archives that have since disappeared from the servers of the Belarusian news website tut.by. By assigning labels like “again,” “hard,” “good,” and “easy” to each piece of material they encounter, a user of this interface can navigate a program that remembers (or forgets) the elements recorded there.

Sign on the facade of the Belarusian Great Patriotic War Museum in Minsk, Belarus that reads, the act of people’s bravery to live forever.

3. Museum of Great Patriotic War: Partisanship and Anti-war Disruptions

In 1967, a new building for the Museum of the Great Patriotic War was constructed in the very center of Minsk, strengthening the status of the so-called Partisan Republic and glorifying Belarus’s World War II partisan heritage with a monumental display. This building, home of a WWII-era collection on the Nazi occupation of Belarus, displayed a giant neon sign out front that read: “The People’s Act of Bravery to Live Forever.” The museum building was demolished in 2014 as part of Lukashenko’s program of historical manipulation. How can something that was supposed to live forever be destroyed so quickly? Soon after, it was resurrected in a new space close to the Minsk Hero City Obelisk (also known as Stella), a monument built in 1985. The monument was erected on the fortieth anniversary of the end of the Great Patriotic war and coincided with the bestowal of the city’s new honorary title— Minsk Hero City—in 1975. In the past two years, the museum has become a significant location within the topography of Belarusian protest.

The weekend after the terrible 2020 elections, protesters gathered in front of the museum. Stella, the monument to victory, was wrapped in a huge white-red-white protest flag. In the following days, the museum was suddenly transformed into a site that the state had to “protect,” by any means, from its people. Military forces descended on the museum every Sunday during the autumn of 2020. Already made rugged from gestures of political subversion and unrest, the space was then surrounded by barbed wire and militarized police forces. This policed border separated the history of anti-fascist movements displayed inside the museum from a contemporary instance of the same struggle.

In a video called F-Word, Belarusian artists Olia Sosnovskaya and AZH trace various contexts in which the concept of fascism is deployed politically—as well as the ensuing social, affective, and symbolic effects.16 They show how each side interprets the concept, and how it is misused in contemporary Belarusian state propaganda. The video features official shots of military parades in front of the museum mixed with various protest activities that reappropriate historical anti-fascist chants and slogans to protest Lukashenko’s regime. This struggle over who or what is the real fascist has become part of the contemporary Belarusian discourse on reclaiming Soviet heritage—including partisanship, histories of anti-fascism, and debates on collective memory. It has been instrumentalized, through media and political rhetoric, by both sides.

One Sunday in winter 2021, when the mode of protest shifted from grand marches to neighborhood organizing, I visited the museum during so-called the Neighborhood Marches. This is a particular type of popular organizing where people meet in their yards (dvory), join with others from their block, and then unite as a whole district. By coordinating via Telegram, people can assemble and disperse depending on the situation. Because thousands of protestors participate in this march tactic, police crowd control is disrupted and frustrated. However, just behind the museum, I saw several police cars and paddy wagons ready for the unannounced appearance of a protest crowd in this symbolic place.

On another recent winter Sunday, the museum was reopened. Almost completely empty except for several Russian tourists, it displayed a bombastic exhibition with more than three thousand square meters dedicated to recounting a newly written master narrative on the Great Patriotic War in ten thematic chapters. With the help of artificial fire, full-scale models of people and weaponry, and flashy projections, the exhibit leads its scant visitors through the horrible, reinterpreted story of war—including monumental battles, Nazi occupation, partisan and underground resistance, and liberation. Contemporary state ideology places victory in that war not so much within a history of collective struggle against tyrants, but as the singular foundation for the current, dreadful iteration of Belarusian statehood. The last room of the exhibition, titled “Heirs of the Great Victory,” was closed. A virtual tour available online shows how the display attempts to concoct a distorted narrative of succession between communist anti-fascism and the contemporary security and military apparatus—the latter of which, in fact, surrendered its territory to the Russian army and also suppressed all existing anti-war initiatives and actions.

Especially now in spring 2022, during the hot, ongoing moment of the Russian military invasion of Ukraine, it is outrageous to see how the Belarusian state has surrendered its infrastructure to the destruction of its neighboring country. Especially considering the irrelevant and vile demand of denazification, which originates in far-right Russian ideology, any supposed shred of “continuity” between anti-fascism and pro-Putinism—or pro-Lukanshenkism—should immediately be broken.

When I exit the exhibition, I see a few heavily armed police officers sitting in their cars behind the museum, getting up only to use the museum toilets. For them, this is probably the only suitable use for the museum and its message.

Looking back on that visit, I recollect mnemonic actors—various objects, artifacts, and devices from the museum collection that could tell another story of struggle, but are currently masked by corrupt ideology.

Several examples of current anti-war disruptions find relevant historical reverberances with these objects and artifacts. For example, an initiative called The Hajun has emerged from the vast network of local anti-war Telegram channels. Hajun is a mythical creature—a forest spirit that nurtures and protects its environment. The channel collects and analyzes the movement of Russian military troops, vehicles, and planes as well as missiles shooting at the territory of Belarus. Participants report looting and other transgressions that Russian soldiers commit in Ukraine. The channel also collects data from hospitals to see the numbers of wounded or dead Russian soldiers.

Cyber Partisans, perhaps the true “heirs” of the historic (Soviet) partisans of the Patriotic War, are an anonymous hacker group who have already leaked a great deal of information from Belarusian state services, including military databases and personal contacts.17 They have physically disrupted the country’s automated railway system and moved it to manual control. Practically speaking, they delayed transportation of ammunition and troops, as railway workers declined to move by night for safety reasons. Other groups of militants, likely organized through the telegram chatbot Victory, have also physically attacked automated railway systems. Activists were detained in these efforts and at least three were wounded by the Belarusian military. Many of them have been charged with terrorist attacks and are probably being tortured and held in inhuman conditions.

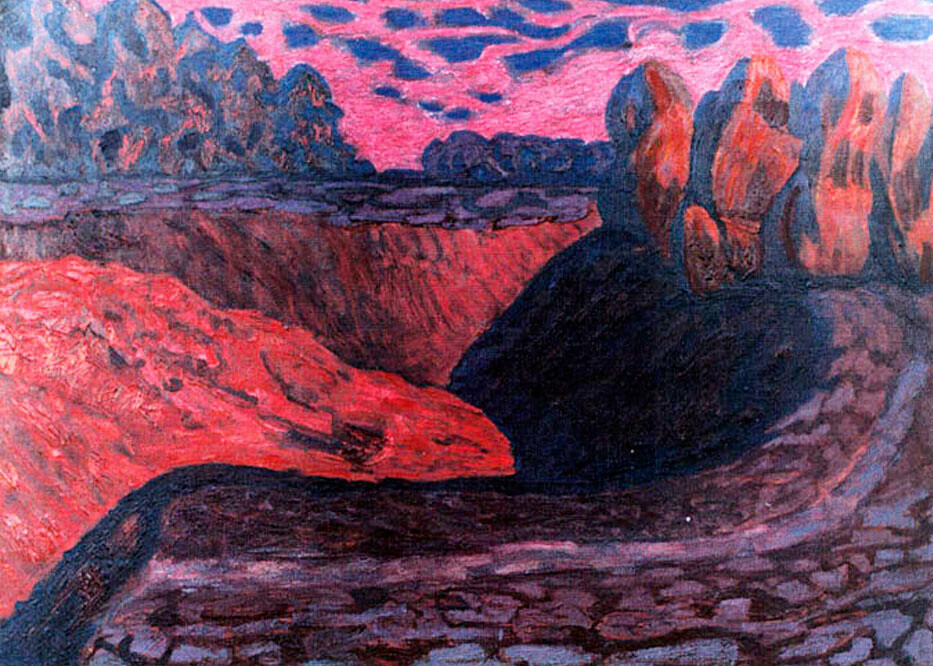

Vladimir Vitko, Vitebsk Trenches, 1974. Courtesy of the artist.

Writing against Conclusions

Fellow writers and artists and I often discuss how to write about situations that have no ending; how to establish cause-effect relations in the spiral of wayward history; and how to refer to previous victories and defeats when history betrays itself. In the temporality of emergency and the excitement of resistance, perhaps another type of conclusion could be found: not a line drawn, not a summing up, but rather a reestablishment of relation between various modalities of time—time understood in all its full queerness. Political and artistic gestures of disruption via algorithmic solidarity and comradely aesthetics do not only question the master narratives imposed by history and ideology. They also seek to prefigure shapes of the future yet to come. Existing outside gestures of individualized expression, they tend to create infrastructures that have the capacity to ferment experiments in collective time travel.

One of the anonymous writers in The Museum of Stones newspaper extracts an object—a partisan vest with portable typography that blends body, resistance, and communication into one wearable form—and removes it from the pressure of museum displays. In a similar way, museums with toxic and possibly atrocious interpretations should be opened up to active questioning, critical assessment, and hospitality for unsettled pasts and futures. If we accept the suggestion that the compression of post-socialist space-time reflects the unstable nature of temporality, its queerness and nonlinearity, then we should be prepared to reach conclusions not from the past via the present, but from the future that is happening now.

Therefore, I would like to finish with a new statement. I support Ukrainian artist Kateryna Lysovenko, whose stated performative gesture is to reclaim anti-fascist and anti-war Soviet art. She says that Russia, with all its atrocities and war crimes, can no longer hold onto this heritage. I join her gesture of releasing Soviet anti-fascist and anti-war art from toxic nationalist and imperialist ideologies. This art belongs to people in struggle and in occupation, to partisans, militants, and refugees.

Slavoj Žižek, Event: A Philosophical Journey Through a Concept (Melville House, 2014), 5.

See →.

Neda Atanasoski and Kalindi Vora, “(Re)thinking Postsocialism,” interview by Lesia Pagulich and Tatsiana Shchurko, Feminist Critique, no. 3 (2020) →.

José Esteban Muñoz, Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity (NYU Press, 2009), 179.

Alena Minchenia and Nadzeya Husakouskaya, “For Many People in Belarus, Change Has Already Happened,” Open Democracy, November 19, 2020 →.

Olia Sosnovskaya, “Future Perfect Continuous,” Ding, no. 3 (2020) →.

Valeria Graziano, Towards a Theory of Prefigurative Practices (MDT, 2017), 181.

Stephen M. Norris borrows this term from Thomas Sherlock, Historical Narratives in the Soviet Union and Post-Soviet Russia: Destroying the Settled Past, Creating an Uncertain Future (Palgrave Macmillan, 2007).

Stephen M. Norris, “From Communist Museums to Museums of Communism: An Introduction,” in Museums of Communism: New Memorial Sites in Central and Eastern Europe, ed. Stephen M. Morris (Indiana University Press, 2020), 4.

Michael Bernhard and Jan Kubik, “Introduction,” in Twenty Years after Communism: The Politics of Memory and Commemoration, ed. M. Bernhard and J. Kubik (Oxford University Press, 2014), 4.

Ірина Склокіна, “Локальні музеї у динамічному світі: (пост)радянська спадщина та майбутнє,” Open Place, November 2015 (in Ukrainian) →.

Н. Чичасова, “Музейное «не так»,” BOHO, April 20, 2021 (in Russian) →.

Saidiya Hartman, “Venus in Two Acts,” Small Axe 12, no. 2 (2008). My exercise in critical fabulation ended up in a collective exhibition called “A Secret Museum of Workers Movements” with works by Gleb Amankulov, Uladzimir Hramovich, Marina Naprushkina, Olia Sosnovskaya, and Valentin Duduk, at Hoast, Vienna in 2021.

Gerald Raunig, “The Molecular Strike,” trans. Aileen Derieg, Transversal, October 2011 →.

From The Museum of Stones newspaper. Translation mine.

The video is part of the “Armed and Dangerous” series curated by Ukrainian artist Mykola Ridnyi.

The notion of partisanship is important here. Partisanship, as a mode of political and creative organization, is also deeply inscribed in the history of Belarusian art—both in socialist realism and contemporary art. For example, in his 1997 photographic series Light Partisan Movement, Ihar Tishin subverted existing narratives by showing partisan bodies in idle yet alert postures. In 1999, the prominent contemporary art magazine Partisan (now called Partisanka to emphasize the role of women in the resistance) was launched.