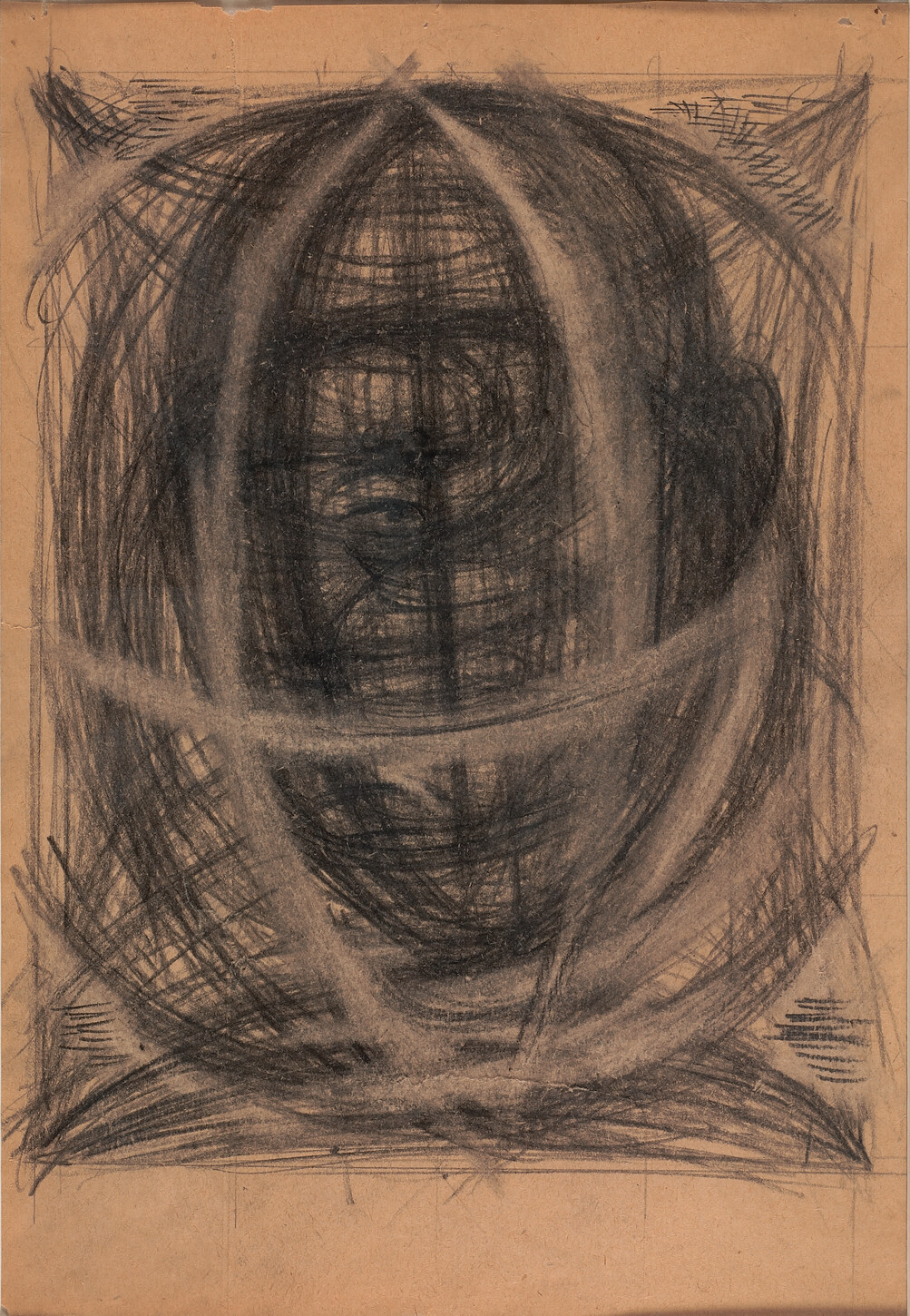

Solomon Nikritin, Oval Composition (Study for a Self-Portrait), 1920s. Watercolor on paper. Courtesy of MOMus-Museum of Modern Art-Costakis Collection. The work was shown in Art without Death, HKW, Berlin, 2017. The exhibition linked a selection of works by the Russian avant-garde from the George Costakis collection – curated by Boris Groys – with contemporary contributions: films by Anton Vidokle and an installation by Arseny Zhilyaev that reflected on the philosophical, scientific and artistic concepts of Russian Cosmism.

1. The Turn from Science to Wisdom in Dialectical Materialism

Beginning in the late 1970s and early 1980s, the term “wisdom” appeared very frequently in Soviet philosophy publications. It was used to better situate the doctrine of dialectical materialism within the history of philosophy as well as in relation to science, art, religion, and so on. Dialectical materialism was itself conceived as a form of “wisdom”: that is, as an insight into the whole of the world which was fundamentally lacking in science and art.

This new self-understanding of dialectical materialism as “wisdom” primarily emerged in the polemic against two of its earlier interpretations—as a science and as an ideology. A good example of this new development is P. V. Alekseev’s book The Object, Structure, and Functions of Dialectical Materialism (1983), which otherwise hews closely to orthodox Marxism. The author seeks to show that Soviet philosophy’s traditional interpretation of dialectical materialism as a science necessarily leads to a needless and nonsensical rivalry between dialectical materialism and the individual sciences. Dialectical materialism, in Alekseev’s view, cannot be one science among others without losing its dominant position. Neither, however, can it be a “total science,” so to speak, that unites all other sciences into a total worldview, as was often asserted in Stalinist-era Soviet philosophy. This interpretation, Alekseev argues, leads to dogmatism, which prevents other sciences from developing autonomously.1

It is also misguided, according to Alekseev, to regard dialectical materialism as a “meta-science” or scientific methodology, since this interpretation similarly leads to a “dogmatism” vis-à-vis the variety of possible theories of science. This cautious attitude toward science no doubt reflects the traumatic experience of Soviet philosophy in the Stalinist era, when many scientific methods and even whole scientific fields (including cybernetics, formal logic, structural linguistics, and above all modern genetics) were banned and persecuted due to their supposed incompatibility with dialectical materialism. On the other hand, it cannot be denied that this caution was implicit in Marxism-Leninism from the beginning. Dialectical materialism is not organized as a closed system of postulates and inferences from them. Logically consistent methodological thinking was already viewed by Lenin as idealistic, bourgeois, metaphysical, and undialectical. The Leninist brand of dialectical materialism understands thinking as “the reflection of objective reality” whereas this reality itself is conceived as dynamic and inherently contradictory. Thus, dialectical materialism is also understood necessarily as an inherently contradictory “living doctrine.” Whereas “bourgeois” thought is concerned to prove its truth with logical inferences that permit it to avoid contradiction, dialectical materialism sees its own internal contradictions precisely as the guarantee of its “vital force.” Within the framework of dialectical materialism, every attempt to think without contradiction has been dismissed since the beginning as “one-sided” and “scholastic.”2 The criterion of truth, for dialectical materialism, is the “total praxis” of social development, except that, in contrast to pragmatism, for example, the practical evaluation of different theories does not take place within a circumscribed period of time but from the perspective of the whole of history.3 The ability of a total overview of history and the whole of the cosmic life presupposed by this conception is given only to the historical force that, while acting within history, can simultaneously look beyond it and thus occupies a privileged position within it. It is only a position like this that makes its holder “wise,” for “wisdom” is nothing other than precisely this possibility of a vision of the whole, which differs from logic, reason, art, etc., in that it rises above all criteria including those of “true” thinking free of contradictions. Needless to say, dialectical materialism discovers a force of this kind in the communist movement, which is able to burst the framework of “bourgeois” thought.

In this respect, the position of dialectical materialism is much more radical, for example, than that of Hegel, who also speaks of the rationality of the real as the highest rationality and whose dialectical method also underlies Soviet Marxism. In contrast to Hegel, the “materiality” of dialectical materialism represents a denial of the final, definitive insight into the rationality of the whole that Hegel accords to the solitary observer: the philosopher.

The final, definitive synthesis does not take place at the level of the individual consciousness at all but at that of the total social praxis. And even more at that of the cosmic process, to which both human history and the individual’s consciousness are subordinated (this is reflected in the subordination of historical to dialectical materialism, which distinguishes Soviet from “Western” Marxism). The supreme principle of Soviet philosophy was: “Being determines consciousness” (which not coincidentally sounds somewhat Heideggerian), with Being here understood as a cosmic-historical process that also includes human creativity. In this scenario, consciousness is not opposed to Being. In contrast to what Soviet philosophy called “vulgar materialism,” “matter” was not conceived merely as an object of experience. According to Lenin, the latter opposition is only relevant for the theoretical-epistemological problematic and must not be imported into the sphere of praxis.4 In Soviet society, the party assumed the role of a subject of the total historical praxis, which on the one hand recalled American pragmatism, but on the other, the Gnostic, magic, or alchemical praxis which had the goal of improving the human soul by creating a new cosmic order that would govern humanity, together with all its “higher” attributes. The supreme magician of this praxis—in the case of the Soviet Union, the General Secretary of the party—was therefore also recognized as the supreme Sage, since it was he who first created the conditions under which all knowledge could unfold.

Solomon Nikritin, Oval Composition (Study for a Self-Portrait), 1920s. Watercolor on paper. Courtesy of MOMus-Museum of Modern Art-Costakis Collection. The work was shown in Art without Death, HKW, Berlin, 2017. The exhibition linked a selection of works by the Russian avant-garde from the George Costakis collection – curated by Boris Groys – with contemporary contributions: films by Anton Vidokle and an installation by Arseny Zhilyaev that reflected on the philosophical, scientific and artistic concepts of Russian Cosmism.

2. The Relationship between Gnosticism and Dialectical Materialism

The domination of magic praxis over scientific theory is strongly reminiscent of Gnostic doctrines that recognized the mastery of the transformative Cosmic praxis as a unique brand of wisdom, because all other forms of knowledge suffered from having arisen under the conditions of this world, which was created by an evil world creator. They are, according to the Gnostics, therefore tethered to this world, can describe only this world, and are already for this reason fundamentally deficient and unworthy. The only type of knowledge that is needed is not of this world. This knowledge would not describe or comprehend the existing world but abolish and destroy it. “Gnosis is the remedy for disintegration and the means of reintegration, because it makes it possible to recognize humanity’s place within the totality and to see through what passes for knowledge in its arrogance—it puts false wisdom in its place.”5 Since the critique of ideology purports to confirm Descartes’s suspicion that the subjective self-evidence of consciousness could be simulated by the malin génie whose name is the “unconscious” or the “material base,” it sees it as its inescapable task to combat this evil genius at its “deep” level, instead of making a pact with it. Philosophy, as Marx demanded, turns into (magic) praxis.

The relationship between modern secular salvation movements on the one hand and Gnostic doctrines on the other was recognized relatively early and discussed in particular by Eric Voegelin. Thus, Voegelin interprets Hegel’s call “to contribute to bringing philosophy closer to the form of science—the goal of being able to cast off the name love of knowledge and become actual knowledge,” as a program of replacing philosophy with gnosis and the figure of the philosophos with that of the sophos, the gnostic.6 In both modern and ancient gnosis, the claim to exhaustive knowledge of the nature of the world that was formerly reserved for the gods or for God is subordinated to the aim of saving the world, or, more correctly, is precisely the knowledge of this salvation: “In modern gnosticism it [the possibility of deliverance] is accomplished through the assumption of an absolute spirit which in the dialectical unfolding of consciousness proceeds from alienation to consciousness of itself—or through the assumption of a dialectical-material process of nature which in its course leads from the alienation resulting from private property and belief in God to the freedom of a fully human existence.”7 The action leading to transformation of the world should precede any questioning of and reflection on it.

Voegelin sees the essential role of modern gnosis as the “prohibition of questioning.” Gnosis places thinking up “against the wall of being” by making the validity of theoretical inquiry dependent on “this world” and thus limiting it. Voegelin writes of this resistance to thought: “This resistance becomes truly radical and dangerous only when philosophical questioning is itself called into question, when doxa takes on the appearance of philosophy.”8

It may be helpful at this point to turn to the extraordinarily astute remarks of Georges Bataille on the relationship between gnosis and dialectical materialism. Bataille begins by defining the latter as “the only kind of materialism that up to now in its development has escaped systematic abstraction,” and he continues: “materialism … necessarily is above all the obstinate negation of idealism, which amounts to saying, finally, of the very basis of all philosophy.”9 Bataille sees in classical gnosis both “one of materialism’s most virulent manifestations” as well as hostility to philosophy. Thus far, Bataille’s analysis is essentially consistent with that of Voegelin’s. This is also the case for his analysis of Gnostic morality, about which he writes: “If today we overtly abandon the idealistic point of view, as the Gnostics and Manicheans implicitly abandoned it, the attitude of those who see in their own lives an effect of the creative action of evil appears even radically optimistic.”10 However, Bataille’s analysis takes a very interesting turn when he then continues:

Thus it appears—all things considered—that Gnosticism, in its psychological process, is not so different from present-day [dialectical] materialism … For it is a question above all of not submitting oneself, and with oneself one’s reason, to whatever is more elevated, to whatever can give a borrowed authority to the being that I am, and to the reason that arms this being. This being and its reason can in fact only submit to what is lower, to what can never serve in any case to ape a given authority. I therefore submit entirely to what must be called matter, since that exists outside of myself and the idea, and I do not admit that my reason becomes the limit of what I have said, for if I proceeded in that way matter limited by my reason would soon take on the value of a superior principle.11

Thus, Gnostics are proud of submitting to what is lower than themselves and hence does not command the allegiance of their reason. In this way, they become the “toys” of a process that, because it is absurd, does not wound their pride. Thus, they also cease to have any actual need for salvation and thus do not call the Gnostic promise into question or measure it against the possibility of its fulfillment. In this way, gnosis becomes perfect and irrefutable. Bataille discovers the symptoms of this consciousness in modern art: “The interest of this juxtaposition is augmented by the fact that the specific reactions of Gnosticism led to the representation of forms radically contrary to the ancient academic style, to the representation of forms in which it is possible to see the image of this base matter.”12

While Bataille here still operates with the ontological hierarchy that distinguishes between the various levels of matter, a fully developed materialism means appropriating and instrumentalizing the “higher” forms within a total materialist praxis that leads to using the ancient art forms in new social and political constellations, as occurred, for example, in socialist realism.13 A rigorous, unswerving materialism does not lead to abolishing ideology, reason, morality, etc., but to include them in the dialectically conceived total praxis, in which they are primarily employed as means of education, mobilization, and of stabilizing the already realized “accomplishments,” so that they become actually quite capable of playing a constructive role in the transformation of reality.

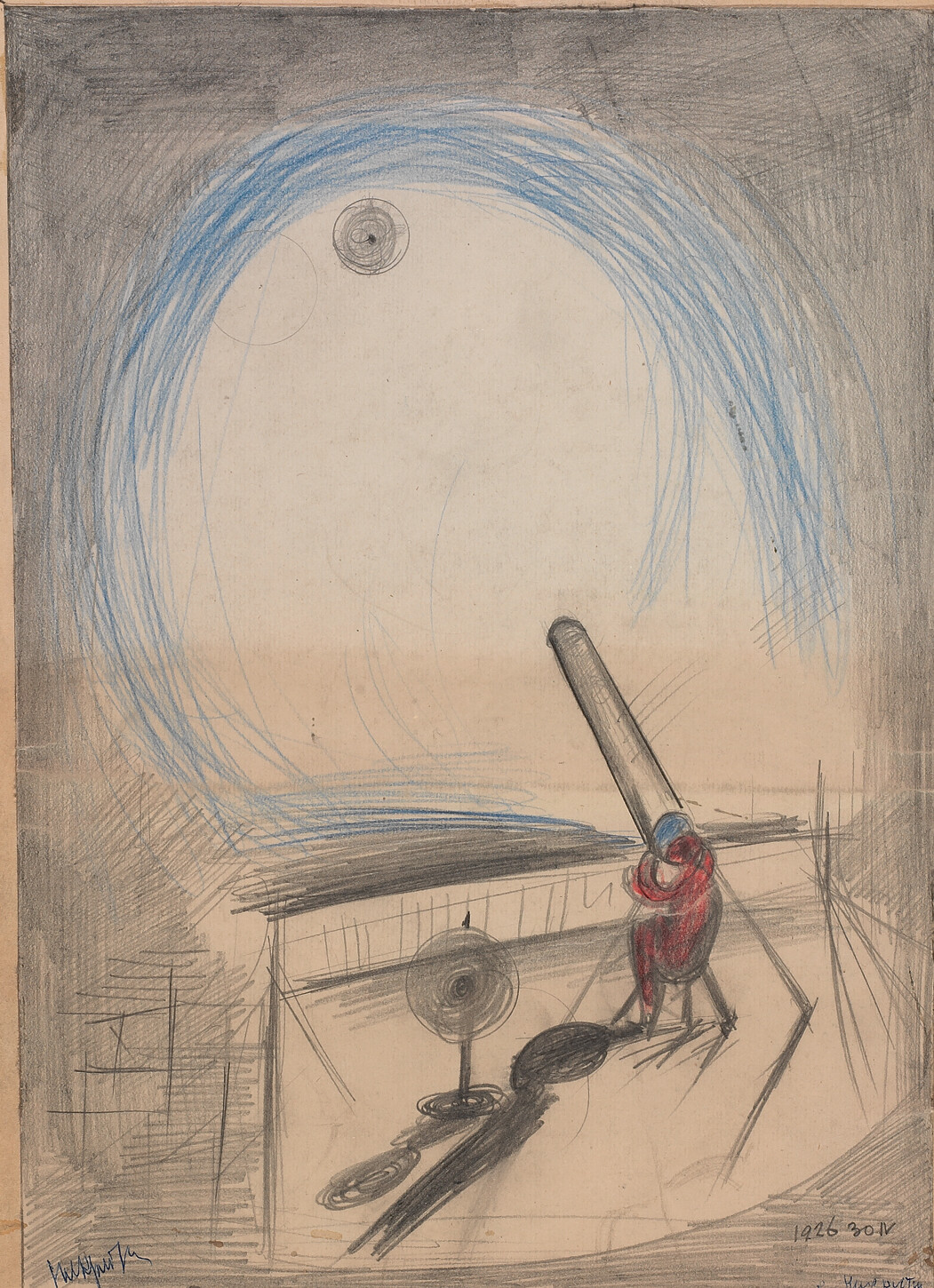

Solomon Nikritin, Telescope, 1926. Pencil on paper. Courtesy of MOMus-Museum of Modern Art-Costakis Collection. The work was shown in Art without Death, HKW, Berlin, 2017. The exhibition linked a selection of works by the Russian avant-garde from the George Costakis collection – curated by Boris Groys – with contemporary contributions: films by Anton Vidokle and an installation by Arseny Zhilyaev that reflected on the philosophical, scientific and artistic concepts of Russian Cosmism.

3. The Relationship between Gnosticism and Dialectical Materialism in the Self-Understanding of Soviet Culture

The close relationship between Gnosticism and the Soviet version of dialectical materialism begins to become clear if one traces closely the latter’s historical emergence. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, when Russian Marxism was taking shape, Russia’s intellectual life was strongly influenced by the neognostic philosophy of Vladimir Soloviev, from which the philosopher largely distanced himself at the end of his life. (Soloviev’s disavowal of his earlier neognostic positions is primarily expressed in his Three Conversations about the Antichrist [1899–1900], in which he creates the self-parodying figure of an emperor-Antichrist who wishes to redeem and reorganize the world without transcending the human nature.) However, Soloviev’s neognostic philosophy exerted a profound influence on all spheres of Russia’s cultural life at the beginning of this century under the name of “Sophiology.”14 This philosophy, which combined the basic Gnostic doctrines with the most modern and radical demands of the Russian avant-garde, as well as with the philosophies of the later Schelling, Schopenhauer, Nietzsche, and Marx, attracted many of the leading figures from the ranks of Russian Marxism. Thus, Semyon Frank, one of their principal representatives, who also traveled the path from Marxism to Soloviev, writes that his own Marxism was characterized from the beginning “by a positive assessment of precisely this moment of a ‘Goethean’ objectivism in Marx, of Marx’s subordination of the moral-political ideal to the immanent-objective, as it were, cosmic principles of social Being.”15

Soloviev’s philosophy was directed toward a mystical, artistic form of action that would transform the world order and lead to the Gnostic apokatastasis. The most interesting example of this kind of project was The Philosophy of the Common Task by Nikolai Fedorov,16 who was Soloviev’s contemporary and proposed the artificial resurrection of the dead as the supreme goal of science, morality, art, the state, etc., through which humanity would close the circle of time in a truly radical manner and become its own creator. Soloviev and Fedorov’s ideas exerted a powerful influence on broad circles of the left-wing Marxist intelligentsia in Russia, particularly the circles around Bogdanov, Lunacharsky, and others with which Lenin was closely associated for many years. The possibility cannot be ruled out that, despite his verbal professions of orthodox Marxism, Lenin was much more strongly influenced by these ideas as well as by Russian Nietzscheanism of the time than is generally assumed. At least there is no other way to explain why he so drastically shifted his attitude towards the concept of ideology.17 In contrast to classical Marxism, in which the word “ideology” had a negative charge (one it has retained up through contemporary Western Marxism), Lenin always uses it positively and speaks of the “proletarian ideology” that will mobilize the masses. Lenin’s defense of ideology is always combined with the affirmation of its “vitality,” its indispensability for “lived life”—expressions that inevitably recall Nietzsche’s “life-sustaining illusion.” For Lenin, the opposite of “false ideology” is not science, but a “correct, progressive ideology” that corresponds to its time, but that may later become a “brake on social development” in its turn. In their radicalism, which is not always adequately recognized, these assessments of ideology’s role, which are present throughout his writings, demonstrate that Lenin’s ideological dogmatism had purely tactical grounds; if it remained unshakeable throughout all the ideological polemics in which he engaged, this may be precisely because it was not actually meant “that seriously” but operated at the level of reflection and action, which was inaccessible to his opponents.

Later Soviet philosophy could be characterized by its interest in the work of Cusanus. It is not just Cusanus’s “dialectics” that is emphasized but above all his rejection of any formulated theory and his striving “for the pure possibility that lies outside this world.”18 (It is also worth noting that Cusanus was a seminal figure for many Russian neognostic thinkers, in particular Semyon Frank.) Cusanus is also appreciated for his polemic against Aristotelianism, regarded as the “official ideology” of the European Middle Ages. In keeping with Lenin’s famous formula regarding “two cultures within a single culture,” whose contest at the intellectual level mirrors the class struggle, Soviet historiography views Thomism as “the official culture of the feudal class,” and various forms of pantheism, mysticism, magic, and alchemy—all of which more or less have their origins in Gnosticism—as the culture of the oppressed classes, which contain “early materialist” and “early socialist” tendencies.

Especially interesting in this regard is Vadim Rabinovich’s book Alchemy as a Phenomenon of Medieval Culture (1979), which attracted quite a bit of attention in its day. In it, the author draws a parallel between alchemy, which he views as having its origins in gnosis and regards as a kind of alternative religion to Christianity, and dialectical materialism.19 In fact, the dialectical development of matter into spirit in dialectical materialism can quite plausibly be compared to the alchemical opus. For as Rabinovich shows, the “alchemical formula” represents a program for achieving the practical and dialectical union of opposites, which is meant to take place beyond both language and contemplation, the alchemist’s “gold” being understood as a metaphor for the spirit or the perfect life.20 The alchemist transforms the world through pure action encompassing all cosmic planes and forces, and in this way rises above the creator of this world. Rabinovich also reinforces the parallel with dialectical materialism by recalling the words of Engels, who refuted Dühring’s sneering dismissal of “the utopian socialists” as “social alchemists” by pointing to the valuable contributions of both the utopians and the alchemists.

In keeping with the above, the relationship between dialectical materialism and gnosis may be characterized as follows. Neither gnosis nor dialectical materialism believes in humanity’s capacity to arrive at true insight into the nature of the world through tradition, contemplation, science, art, morality, or by any other means, since people’s positions in this world determine and thus relativize all their insights. The critique of this world is therefore only possible as its transformation, as an action in which all partial forms of wisdom and partial insights can and must play only an instrumental role. Their own claim to truth is understood as “metaphysical” or “idealistic” and rejected. The supreme wisdom of gnosis is precisely this insight into the impossibility of all insight, which legitimates the claim of Gnostic doctrines to absolute power.

The difficulty with this turn to “apophatic materialism” is clearly that, while the belief in the determination of human thought by its positioning in the world (by its “individuality”) is retained, the possibility of describing the corresponding world structure scientifically (or in any other way) is denied. That means the recognition of human freedom—however, the nature of this freedom remains unspecified, as does the corresponding dialectical-materialist-alchemical formula for changing the world. If “discovering their individuality” for human beings means determining their position in the world, in “apophatic materialism” this ceases to be possible. However, radical skepticism in the spirit of the cogito ergo sum also ceases to be possible, because if the cogito is determined by the sum, but the sum remains indeterminate, then the cogito as well as its radicalization in critical action remain indeterminate as well.

When skepticism loses its radicality, it no longer represents a total distancing from the world, tradition, everyday life, etc., but only a partial distancing in certain respects, and as a result the world-changing action becomes merely partial as well. Even more importantly, however, this action can no longer be “individual” or “original” (either in the sense of being “new” or “unusual” or in that of “proceeding from the origin”), that is, “productive,” but only reproductive. This means, however—and the consequence is observable—that the “negative,” “mystical” radicalization of dialectical materialism which opens a specific path to postmodernity is accompanied by a cynical realism in the sense of a total simulation of the “ideological superstructure.” This is a self-reflection, however, that lies far beyond the reach of Soviet dialectical materialism.

Petr Vasil’evich Alekseev, Predmet, struktura i funkcii dialekticeskogo materialisma (Moscow University Press, 1983), 25–26.

For more on the theory of contradiction in Soviet Marxism-Leninism, see Boris Groys, “The Problem of Soviet Ideological Practice,” Studies in Soviet Thought, no 33 (1987): 191–208.

For more on the criterion of praxis, see Vladimir Ilyich Lenin, Materialism and Empirio-critics: Critical Comments on a Reactionary Philosophy →.

Lenin, Materialism and Empirio-critics.

Peter Koslowski, “Über Totalismus. Metaphysik und Gnosis,” in Oikeiōsis: Festschrift für Robert Spaemann, ed. Reinhard Löw (Acta Humaniora, 1987), 101.

G. W. F. Hegel, The Phenomenology of Mind, 2nd ed., trans J. B. Baillie (G. Allen & Unwin, 1949), 70; as quoted in Eric Voegelin, “Science, Politics and Gnosticism,” trans. William J. Fitzpatrick, in Science, Politics and Gnosticism: Two Essays (Gateway Editions, 1968), 40.

Voegelin, “Science, Politics and Gnosticism,” 11.

Voegelin, “Science, Politics and Gnosticism,” 20.

Georges Bataille, “Base Materialism and Gnosticism,” in Visions of Excess: Selected Writings, 1927–1939, ed. Allan Stoekl, trans. Allan Stoekl with Carl R. Lovitt and Donald M. Leslie Jr. (University of Minnesota Press, 1985), 45.

Bataille, “Base Materialism and Gnosticism,” 48.

Bataille, “Base Materialism and Gnosticism,” 49–51 (translation modified).

Bataille, “Base Materialism and Gnosticism,” 51.

See Boris Groys, “Die totalitäre Kunst der 30er Jahre: Antiavantgardistisch in der Form und avantgardistisch im Inhalt,” in “Die Axt hat geblüht …”: Europäische Konflikte der 30er Jahre in Erinnerung an die frühe Avantgarde (Städtische Kunsthalle, 1987), exhibition catalogue, 27–35.

See Boris Groys, “Wisdom as the Feminine World Principle: Vladimir Soloviev’s Sophiology,” e-flux journal, no. 124 (February 2022) →.

Semyon Lyudvigovich Frank, “Die Häresie des Utopismus,” Impulse (1983): 18. An English translation of this essay was published as “The Utopian Heresy,” The Hibbert Journal, no. 52 (1953–54): 213–33.

Nikolai Fedorov, Filosofia obščego dela (Éditions L’Age d’Homme, 1985).

See Helmuth Dahm, “Der Ideologiebegriff bei Marx und die heutige Kontroverse über Ideologie und Wissenschaft in den sozialistischen Ländern,” Berichte des BIOst, no. 63 (1970).

Piama Gaïdenko, Evolucia ponjatija nauki (The evolution of the concept of science) (Nauka, 1980), 527.

Vadim Lvovich Rabinovich, Alchimija kak fenomen sradnevekovoj kul’tury (Nauka, 1979), 167–68.

Rabinovich, Alchimija, 62–65.

Translated from the German by James Gussen. Unless otherwise specified all translations of quoted material have been translated from the use in the German publication. This text has been edited for length and clarity.