1. Only Revolution Ends War

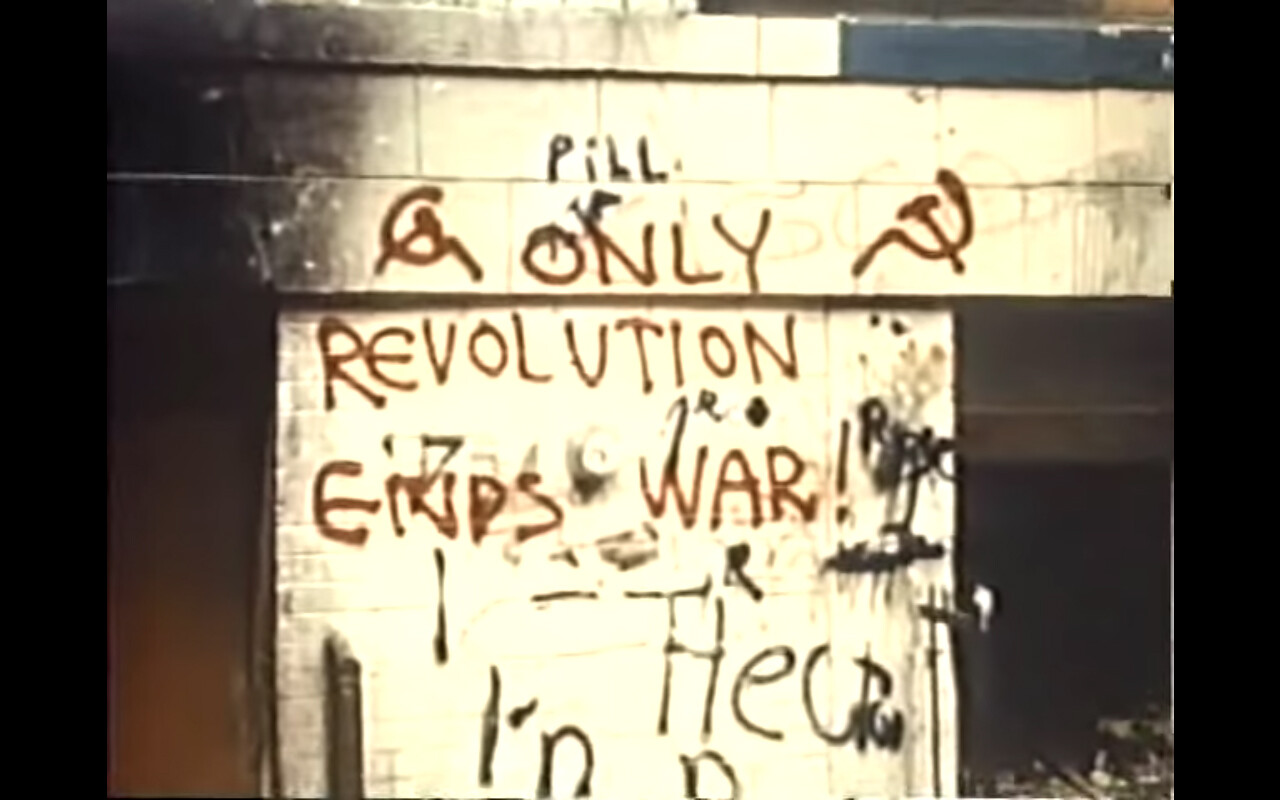

One of the masterpieces of avant-garde film history, Dušan Makavejev’s W. R.: Mysteries of the Organism (1971), begins with documentary footage of an anti-war performance by the counterculture poet Tuli Kupferberg of the band The Fugs. We are somewhere on a street in New York’s East Village. The wall behind the performers is covered in graffiti: a row of hammer-and-sickles and “Only revolution ends war,” most probably a quote from Trotsky. We are in the late 1960s, when the US is deeply entangled in the Vietnam War.

Today, when the morbidity of Russia’s war on Ukraine consumes our minds, let’s recall the event this scene documents: May 1968 and the utopia of love and peace coming together in revolution. Without this utopia, we cannot understand the Ukrainian catastrophe, nor see any way out it.

But first, a few more words on Makavejev’s film. It was about Wilhelm Reich’s idea of sexual revolution, which ultimately gave meaning to the main American anti-war slogan of the time: “Make love, not war!” The notion of love implied sex, and consequently sexual freedom—but not in the liberal sense of merely emancipating sex from the constraints of a conservative society so it can be enjoyed freely. Sexual revolution goes beyond the idea of sex needing freedom. Rather, it’s the other way around: freedom needs sex because of its emancipatory potential, which can be mobilized to change the world—to liberate it from war, for instance. This was too utopian for liberals, whose counterrevolutionary appropriation of sexual freedom separated it not only from the idea of revolution, but also from the ideal of peace. Instead, sexual freedom became a juridical matter within the nation-state and subsequently a feature of Western cultural identity; indeed, it became a so-called “Western value.” Today, sexual freedoms are the benchmark of the civilizational difference between the West and the Rest.

But what does this have to do with the war in Ukraine?

2. It’s a Proxy War

The miserable reality of the war in Ukraine has very quickly found its equivalent in the cognitive misery of its liberal representation in Western publics. The mainstream media pushes a story about the Ukrainian nation heroically resisting Putin’s aggression—and it’s true that the Ukrainians defend their land heroically, and we can only hope that they will break the back of the Russian invaders. But there is one major flaw in this story. The Ukrainians, against their will, have been forced into this war and must now fight it, but not only for themselves: they must fight as a proxy for the West. The war in Ukraine has become a proxy war between two imagined adversaries, the West and Putin—who is depicted as a rogue autocrat, an evil totalitarian dictator who suddenly went mad, turning order into chaos and inflicting suffering on millions of innocent people, even bringing the world to the edge of nuclear catastrophe. In the figure of a mad Putin, the West has created an ideal enemy, entirely personified, pathologized, and ostracized.

As such a madman, Putin embodies a problem that can be not only projected onto the civilizational other of the West, beyond the scope of its rationality, but also easily removed. This has given rise to fantasies about a palace coup in the Kremlin that would eliminate the evil autocrat and solve the whole problem in one fell swoop. Such a coup d’état, it’s believed, could end the war and return things to normal. But what would this normality actually mean beyond the happy return of McDonald’s, Ikea, and H&M to Moscow? Would it mean, for instance, that Russia welcomes Ukraine’s accession to the EU and NATO? That the Schengen regime is extended all the way to Ukraine’s border with Russia? That Crimea is restored to Ukraine, and Sevastopol becomes a NATO naval base? If this had not been the West’s idea of normality, the war could have probably been avoided. But why bother avoiding it when the price is paid by a proxy?

Unfortunately, mainstream media coverage of the war in Ukraine offers similarly few clues about the adversary on the other side of the frontline—the West. The notion of “the West” gives the impression of an acting subject: “the West must act,” it “has its strategy,” it “has made its decision,” it “imposes sanctions” and “supplies arms.” Sometimes, as we know, it also wages wars. But beyond one of the four cardinal directions, what the hell is this “West”? Is it a democracy? Has anyone elected representatives into its parliament? Are there free democratic elections in which the people of the West choose their government and president? Does the West have laws, a secretary of foreign affairs, a ministry of defense? “The West” has nothing like that, but plenty of culture, money, and bombs instead.

3. Cui bono?

The question becomes: What has brought these two imagined adversaries, Putin and the West, into war against each other? The rationale given by Putin makes no sense. As much as NATO’s expansion to the east is a historical mistake of the West, NATO has not directly threatened Russia—not to any extent that could be an alibi for war. Putin’s czarist imperial fantasies are certainly one motivation, as parts of Ukraine—due to historical, linguistic, and cultural closeness to Russia—could be perceived by Putin as a kind of no-man’s-land where borders can be redrawn. But such a massive attack clearly aims at what the West calls “regime change.” Even in Russia itself, Putin’s rule was not seriously contested enough for him to need a war abroad to silence the opposition at home. In fact, if anything threatens his rule at all, it’s this war. So, cui bono? Who stands to benefit from this war?

Though it may sound like a paradox, it seems that this war was needed by everyone except Putin, the Russians, and those who are now dying in it. If the Ukrainians as a nation have not yet been culturally and politically united—if, in other words, their nation-building process has not yet been completed—then Putin is now doing the job better than the most ardent Ukrainian nationalist. All those cultural rifts, political antagonisms, and, especially, class divisions that, until yesterday, tore the nation apart are now closed with the strongest possible glue, the Ukrainian blood spilled by Putin’s forces making Putin the ultimate unifier of the Ukrainian people. The European Union looks like another beneficiary of the war. Only yesterday, many spoke openly about the real prospect of disintegration, about Brexit spreading like gangrene, about excluding the illiberal renegades on the EU’s eastern flank. Now, almost overnight, all the members of the EU stand together firmly under the slogan “All for one, one for all!” Boris Johnson’s Covid parties are forgotten, Germany has finally gotten rid of its guilt complex, Poland has reemerged as the bulwark of the West against the barbarians from the east.

The other side of the Atlantic has benefited even more. The shameful debacle of the United States’ withdrawal from Afghanistan and the coup attempt on Capitol Hill, which brought to light the deep crisis of American democracy, seem to have both vanished into the distant past. Or take NATO itself. Only recently declared “brain dead,” today it rises again in full force. If before it had neither strategic nor moral justification for expanding to the east, now it has both. The decision to expand across the former Cold War divide now seems like a self-fulfilling prophecy. Finally, Putin has just launched a new phase of the global arms race, and with it a new cycle of capital accumulation. What luck for the military-industrial complex of the West! The opening of champagne bottles in its offices was probably louder than the roar of Russian cannons on the first day of the invasion. And there will be jobs for the surviving Ukrainians as well. Why toil over ploughshares when one can forge swords?

But there is one more collateral gain for the West in this war, an ideological one. Western publics are now vindicated in their dangerous self-delusion that criminal wars are waged only by non-democracies like Putin’s Russia. This is simply not true. A senseless, unjust, and bloody military aggression abroad, even if met with strong protest at home, can nevertheless gain the blessing of democratic institutions. Western democracy offers no protection against involvement in criminal wars; the rule of law, a strong civil society, and a free and independent media are of no help in this matter.

Still, whatever benefits are reaped by the West in this war, the question remains: How has Putin so easily accepted the role of the West’s useful idiot?

4. As a Condition for Their Survival

There is no dilemma whatsoever when it comes to assigning direct responsibility for the war in Ukraine: Putin and his Kremlin cabal are to blame. Even their demands imposed on Ukraine as conditions for peace are no more than blatant swindles: for demilitarizing Ukraine, it’s already too late, unless this also includes demilitarizing Russia and the West; denazification is no less nonsensical, unless it’s applied equally to Russia, beginning with Putin himself and his ultra-right clique—and this too should ideally extend to the West, to Poland, and further to Germany and France.

The only demand that seems acceptable for Ukraine now is to abstain from NATO membership, which raises the question: How did we arrive at this point in the first place? Does the West bear any responsibility for drawing Ukraine into NATO? Was this ever a smart or responsible path to pursue? Unfortunately, this question cannot be answered. There is no entity whatsoever that can take responsibility for what “the West” does. Rather, it seems that total irresponsibility—or more precisely, a priori impunity—is the very essence of the West. Even within the West, of course, there is no equality among Westerners. A Croat can be held accountable before a tribunal in the Hague, yet it’s impossible to imagine an American, British, or French citizen being tried there, regardless of what they have done. On the contrary, when they commit war crimes—which they sometimes do—the person who reveals the truth about those crimes might be incarcerated, despite the rule of law, despite a strong civil society, despite a free and independent media. There is no need for Stalinist show trials when one can simply leave people to disappear into the labyrinthine judicial system before our very eyes, with our full knowledge of the injustice. This is what is now happening to Julian Assange.

However, the West’s total irresponsibility does not necessarily exclude its total responsibility, at least when it comes to the United States. In 1997 Václav Havel, the most prominent of all East European dissidents and at that time the president of the Czech Republic, gave a speech in Washington with a very telling title: “The Charms of NATO.” Havel enthusiastically welcomed NATO’s decision to admit Poland, Hungary, and the Czech Republic, and called for the US to assume responsibility for the whole world. For Havel, only the United States could save our global civilization by acting on its values—values that should be adopted by all cultures and all nations, as a condition for their survival.

This megalomaniacal vision is obviously no less delusional than Putin’s dream of a “Russian World.” The fact is that the fantasy of global domination through imposing one’s own values on everyone else is impossible. The planet we live on simply doesn’t have enough resources to provide the “American way of life” to everyone, unless one believes that democracy can flourish amidst the endemic poverty, extreme exploitation, chaos, and corruption typical of life on the periphery of global capitalism—where profits are made to fund the high living standards of the consumerist middle classes in core capitalist countries.

5. Does Anybody Speak of “the Former West”?

Let’s get back to the point: the total irresponsibility and total responsibility of the West are two sides of the same coin. The fact that they don’t come into conflict is due to a censorship technique called “whataboutism”—a taboo that the liberal mind has imposed on dialectics in general. Not only is it considered improper to speak of obvious contradictions, but we feel obliged to always “stick to the facts” and think “realistically”—divorced from any utopian possibility. Take as an example the problem of returning occupied Crimea to Ukraine. The only “realistic” option to achieve this would be a Western victory in a nuclear Armageddon. If this is the “realistic” option, then we have every right to offer a more realistic one: a vision of a radically changed world in which a demilitarized Crimea belongs to the people who live there, people who—whether Ukrainian, Russian, or otherwise—build a social and environmental future for their children, sink destroyers and cruisers to make fish hatcheries, plant tomatoes in overturned tank turrets, and grow pea vines around rifle barrels. This may sound like a revolutionary utopia, but it’s already too late for anything else. Moreover, without understanding the ideas of utopia and revolution, we cannot see how we have arrived at such a dystopian dead end.

Of course, there are many in the West who are very critical of the West’s role in the war on Ukraine. These critics mostly point at NATO’s decision to expand eastward following the collapse of the Soviet Union. The West, they argue, should have instead integrated Russia into the European security system. While this sounds like a realistic critique, it still lacks a broader historical dimension. It’s not a question of this or that wrong decision by Western security officials, but of an epochal failure.

Immediately after the so-called fall of communism in Eastern Europe, there was a moment of total historical openness in which a radically different, better world seemed like a realistic possibility. Words like “freedom,” “democracy,” and “justice,” proclaimed by those who had fought for them, sounded like calls for unrestrained imagination. This is why the event was called a “revolution,” or more precisely, the “democratic revolutions” of 1989–90. Yet the Western liberal mind acted promptly to contain such revolutionary fervor by appropriating the idea of revolution and depriving it of any utopian dimension. The upheavals came to be called the “catching-up revolution” (Habermas: die nachholende Revolution), meaning simply that the East was catching up with the West. More concretely, the East was adopting “Western values,” from parliamentarism and the rule of law to the fire-sale of entire national economies—the shock therapy of neoliberal capitalism.

The main ideological tool deployed by the West to achieve this goal was taken from the arsenal of its colonial legacy: the concept of civilizational difference. Seen now through a quasi-anthropological lens, the post-communist East appeared not only as a cultural other of the West, but also as a historical relic—a belated and inferior civilization. In the bizarre concept of the “former East,” the West found the means to resurrect its Cold War counterpart. The old couple was back on stage, separated by civilizational difference, yet bound together by a common denial of history: the West was beyond history because it had itself become the very measure of historical time; and the East was burdened by a past that had no value whatsoever, since it was merely the history of its civilizational belatedness. At the end of the 1990s, Slovenian art critic Igor Zabel, appalled by the persistence of the old blocs, challenged the prevailing notion of the “the former East” by asking: “Does anybody speak of ‘the former West’?” There was no answer. The West succeeded in preventing historical change from spilling over into its own bloc. Revolution was fine insofar as it only went halfway—that is, not beyond the East. But in the words of Saint-Just: “Those who make revolution halfway only dig their own graves.”

6. How to Make People Sick of Revolution in One Easy Step

Isn’t it ridiculous to talk about revolution today? Isn’t the concept totally discredited? Indeed, this is among the greatest ideological achievements of the liberal mind. The capitalist West—above all, the United States—has worked diligently on this since the end of World War II, not only politically and militarily, but culturally and cognitively. The crucial influence of the CIA and big private foundations like Ford, Rockefeller, and Carnegie on academic scholarship and more generally on intellectual circles (mostly left-liberal) in postwar Europe is well documented. Their strategic focus was the expansion of the social sciences, and they tactically targeted the concept of history. For instance, during the postwar period French historians were motivated by generous financial support to study longue durée structures and recurring historical cycles instead of social movements and singular historical events. As Kristin Ross has argued, this prompted not only the erasure from historical consciousness of the very possibility of abrupt change or mutation in history, but also an abandonment of the idea of revolution itself.1 By the 1980s Europe had already forgotten the revolutionary origins of its own democracies; it was even ashamed of them. Yet the final blow to the idea of revolution was delivered by the West after 1989 with the proliferation of so-called color revolutions: “Orange,” “Rose,” “Tulip,” and so forth, followed by a variety of “Springs.” Most of these revolutions thought of themselves as nonviolent, yet many of the hopes they raised eventually drowned in a sea of blood. Ukraine is no exception.

The culmination of this revolutionary adventure of the West was the creation of a team of professional world revolutionaries in the guise of the Serbian movement Otpor (“Resistance”), a group of young activists involved in the overthrow of Milošević. They were trained by US operatives in Hilton hotels and showered with money—allegedly millions of dollars. The liberal Guardian, in the manner of the cheapest Soviet propaganda, hailed the leader of the group, Srđa Popović, as no less than a “secret architect of global revolution.”2 Members of Otpor have advised and trained so-called pro-democracy and pro-Western activists in about fifty countries, including India, Iran, Zimbabwe, Burma, Ukraine, Georgia, Palestine, Belarus, Tunisia, Egypt, Venezuela, and Azerbaijan. They have also turned their revolutionary skills into academic knowledge (“the new but fast-growing academic field of non-violent struggle, the influence of which is felt around the world”3), which they teach at prestigious Western universities like Harvard, NYU, Columbia, University College London, and so forth. They even write guides for revolutionaries with titles like “How to Start a Revolution in Five Easy Steps: Humour and Hobbits, but No Guns.”4 Of course “no guns,” since the West cannot stand the sight of blood unless it spills it itself.

The fact is that most of the revolutions Otpor has advised have failed. Yet the West has still succeeded at one thing: making people sick every time they hear the word “revolution.” The figure of the revolutionary has become synonymous with manipulating the democratic will of the people, with moral and intellectual corruption, and with the falsification of the real emancipatory experience of social struggle.

7. Missing Lenin

What is missing today in the bloody drama in Ukraine is the idea of revolution. Or more precisely: we miss Lenin—a figure who radically challenges the binary logic behind the clash between two normative identity blocs. The West and Putin’s Russian World each stake out an exclusive territory that is defined by their respective “values,” which are in fact two sets of arbitrarily essentialized, sharply differentiated qualities. The West, as always, cherry-picks—“civilization,” “democracy,” “freedom,” “the rule of law, “open society”—and has more recently sought to incorporate gender equality and LGBTQ rights as well. Putin’s counter-bloc is arguably not so noble and might be summarized by a simple formula: “Russian soul plus czarist imperialism minus gay parades,” co-drafted and wholeheartedly endorsed by the Russian Orthodox Church.

Lenin and the Bolsheviks stand for what these two warring identity blocs deny, and also what unites them beyond all arbitrary differences. Firstly: the two blocs occupy complementary and at the same time contradictory positions within the power structure of global capitalism, which constantly generates and is itself generated by such antagonisms—not only between these two identity blocs, but also in relation to their global other, the Global South. Lenin knew this. Even if Lenin’s concept of imperialism no longer applies to our contemporary situation, it still reminds us that there is no capitalism without injustice, violence, and war. Forgetting this fact was merely a short-lived privilege of the West, rarely granted to the Rest. This is why “only revolution ends war.”

Secondly: both blocs equally disavow the historicity of their so-called values. This disavowal is constitutive of their identity, since it stabilizes the boundary between them. Yet the legacy of the Russian October blurs this boundary and dissolves the very idea of normative identity blocs. This is why Lenin and the Bolsheviks are Putin’s true nemesis and why we do not find “revolution” among the essential qualities of the West.

The Bolshevik Revolution not only overthrew the Russian Empire, executed the czar (who had pushed his people into a bloody imperialist war), and laid the political and cultural foundations for modern Ukraine. It went further. Today, when Russia outlaws the so-called public promotion of homosexuality, it should be remembered that Bolshevik Russia already decriminalized homosexuality in 1918. Soon thereafter, abortion was legalized and women were given the right to divorce by simply writing a letter. Bolsheviks passed progressive, gender-neutral marital and family laws unlike anything seen in the modern world. A few years later, a Soviet court declared a marriage between two people of the same gender legal, on the grounds that it was consensual.5 These achievements of the Russian October are undeniable, even if Stalin reversed many of them in the 1930s.

What does this tell us? For one, that even by the standards of liberal “values,” Lenin’s Russia was ahead of not only the West of its time, but also the West of ours. It also tells us that those so-called “values” are nothing more than irreducibly contingent results of social struggle. More importantly, it tells us that our imagination must reclaim the idea of fast and radical change—as a condition for our survival.

What is the alternative? The West and NATO, after defeating Putin, resume expanding until the whole world becomes “Western”? This project has shamefully failed. NATO has become a truly defensive force with one single task: to fortify and protect Western values within its identity bloc. But this is already a recognition of defeat. What else is this “West” today if not the name for the self-defeat of the liberal mind, which mistook freedom for an identity and enclosed it behind civilizational difference? This defeat is the late revenge of colonialism’s legacy, which the West has never truly reckoned with. The ideological ghost of this legacy, which still haunts the West to this day, is the fatal binarism of “the West and the Rest”—and this binarism is what escalates antagonisms now, what incites violence and wars (not necessarily fought by the West itself). What has made Putin “mad” and, by the same token, a useful idiot of the West is this same exclusive binary logic: either the West or the East. In short, his madness consists of what is most Western in him: his identification with essentialist cultural difference and the construction of an identitarian counter-bloc—his delusional Russian World. Worse, this same binary logic—either the West or Putin—is shared by Putin’s opposition at home, making it ineffective against Russian nationalism. In the opposition’s mind, and more generally in the minds of the East European left, the Cold war never ended. It’s still an exclusive disjunction: either the West or catastrophe.

The true catastrophe that has turned Ukraine into a killing field is precisely this binarism in which the West fights the very ideological monster it itself created. This war erupted not because the West should have penetrated even further into its eastern other, now called the “Russian World.” Rather, it had already penetrated too far—with the binarism of primitive accumulation (private vs. state property) that devastated this whole space and installed oligarchic rule. It’s this same binary deadlock that prevents us from imagining any end to this war beyond the dystopian vision of a fragile armistice among ruins and hatred. How much time will it take to heal the wounds of this war that divides not just two nations and millions of families and friends, but also two civilizations, two worlds? Already we hear that it may take hundreds of years. Do we have that much time?

What Russia needs today is not a coup d’état that supposedly return things to normal. It needs a revolution—a Leninist one with genuine revolutionary violence that will not only remove Putin and his clique from power (he deserves the same fate as Nikolai II), but also destroy his entire system of oligarchic crony capitalism, expropriate the criminal expropriators, and call the oppressed of the world to join the struggle. But this is exactly what the West fears most.

The system of parliamentary oligarchy that upholds Putin, with its authoritarian and violent character, is not an exclusively Russian invention. It’s the system that best serves the interests of the global ruling class today. This is why there has been so much sympathy for Putin among right-wing circles around the world. If Putin dies, someone else will carry his flag onward, not only in Russia but in many other places around the world, including the West.

8. Again: Only Revolution Ends War

Some thirty years ago now, Yugoslavia collapsed after a series of bloody wars. Already at the time, Giorgio Agamben offered a rather dystopian vision of what would follow in his book Homo Sacer.6 He argued that the collapse of Yugoslavia should not be regarded as a temporary regression into a state of nature and a war of all against all, which would then be followed by new social contracts and the establishment of new nation-states. Rather, he said that the conflict marked the emergence of the state of exception as a permanent condition. In the Yugoslav wars, and more generally in the dissolution of Eastern Europe states, Agamben saw “bloody messengers” announcing a new nomos on earth. If not confronted, this nomos would overtake the planet, wrote Agamben. Invoking Carl Schmitt’s thesis on the disintegration of the Westphalian order, Agamben suggested that this new nomos would be a post-Eurocentric global system of international relations dominated by “large spaces”—or what we can see today as normative identity blocs. In this transformation, as Schmitt had predicted, Europe and the West would lose their dominant position in the configuration of world power.

We should bear this in mind amidst suggestions that the West, the EU, and NATO are regaining their splendor, united as never before. This is an illusion created by Putin. The West has no ideological capacity to confront the major global problems of today. A look at the postwar reality of the former Yugoslavia is a sobering reminder of this impotence: deindustrialized and depopulated wastelands, nation-states whose sovereignty is a cruel joke, war criminals celebrated as national heroes, and new borders that violate international law but are at least partially recognized by the West. In short: Agamben was right, and he will be right again when it comes to Ukraine’s postwar reality.

This also retroactively explains why the West failed in the former Yugoslavia. It did not have a vision of democracy that went beyond the nation-state. The reason for the war was not the civilizational difference between Western/European democracy and the endemic nationalism of the Balkans, but rather the final Westernization of the country, which imposed the logic of the nation-state in a space of extreme cultural, linguistic, and historical heterogeneity.7

The worst is yet to come. The West still has no vision of democracy beyond the nation-state, which is why an entity like “the West” exists in the first place: as a cultural and normative ersatz for its own lack of utopian imagination and revolutionary courage. This is why, when faced with a crisis, the EU suddenly forgets its noble values and relies on something much more sinister: The president of the European Council, when addressing the question of why the EU treats refugees from Ukraine differently from those of other war-torn countries, declared that Ukrainians and Europeans belong to the same “European family.”8 However sweet and benevolent, this metaphor can only mean that the EU is a community united by blood. Can unity through “soil” be far behind?

The former Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia was not built on an identity. Its legitimacy was based on a twofold utopia, which emerged from the 1948 clash with the Stalinist counterrevolution. The first dimension of this utopia was an expansion of democracy into relations of production and labor rights—the so-called system of self-management. The second expanded democracy as an active politics of peace into the sphere of global international relations through the Non-Aligned Movement, which Yugoslavia cofounded. While the first project dealt with the limits of democracy intrinsic to the capitalist mode of production, the second addressed the emancipatory interests of what was then called the “third world” as it emerged from anti-colonial struggles. In this way, Yugoslavia challenged two fundamental binaries of our age: private vs. state property, and the West vs. the East.

The events of 1989–90 doomed these utopian projects (which admittedly suffered from their own shortcomings and contradictions). The notion of democracy that won the Cold War regarded itself, in the old colonial manner, as inherently superior (and Western), thus justifying its expansion throughout the empty space-time of the postcommunist world. Reveling in this “triumph of democracy,” the liberal democratic mind was uninterested in learning from the failures of the democratic utopias that had been born from anti-capitalist and anti-colonial struggle.

What the ideological clash provoked by the invasion of Ukraine desperately lacks is a utopian vision of peace and reconciliation that will end the war, a vision that goes beyond a fragile armistice. Such an armistice can only produce a permanent state of exception, leaving everything to longue durée processes of mentality change, the creation of an appropriate memory culture, the prosecution of war criminals subsequently celebrated as national heroes, and the painfully slow transformation of nondemocratic oligarchies into slightly-less-nondemocratic oligarchies. This might eventually succeed, but in the relative eternity of liberal realism, we will all be dead by then.

Let revolutionary history and its utopian imagination suggest another vision of peace and reconciliation for Ukraine and Russia today:

The first step of the Revolution is successful and peace soon returns to Ukraine. Some Russian soldiers fraternize with their former Ukrainian enemies, while others abandon the frontlines en masse, eliminating any officers who get in their way. At the Kremlin, members of the revolutionary committee draft a new law to expropriate the oligarchs. A day earlier, in the basement of the palace, the perpetrators of the criminal war in Ukraine were executed. The process was much shorter for them than it was for Nicolae and Elena Ceaușescu. But who will guard the leaders of the Revolution in their Kremlin headquarters? The oligarchs have already assembled private armies—lavishly financed, professionally trained, and well-armed by the West and NATO. History again has an answer: Ukrainian fighters, the best soldiers for the job, just like the Latvian riflemen who protected Lenin in Smolny more than a hundred years ago. And though there will surely be violence and losses, there will no longer be hatred between Ukrainians and Russians in their common Revolution. Only revolution ends war.

Does this sound too utopian? Perhaps, but there is no time left for anything else. Unless we reclaim the utopian vision of radical and rapid change, we are doomed. If they don’t nuke us first, we will be burned by the sun.

Kristin Ross, Fast Cars, Clean Bodies: Decolonization and the Reordering of French Culture (MIT Press, 1994), 189.

Jon Henley, “Meet Srdja Popovic, the Secret Architect of Global Revolution,” The Guardian, March 8, 2015 →.

Henley, “Meet Srdja Popovic.”

Srđa Popović, “How to Start a Revolution in Five Easy Steps: Humour and Hobbits, but No Guns,” The Guardian, March 9, 2015 →.

The marriage was between a cisgender woman and a trans man who was still legally regarded as a woman. See Edmund Schluessel and Sosialistinen Vaihtoehto, “100 Years Ago, a Forgotten Soviet Revolution in LGBTQ Rights: Review of Dan Healey’s book Homosexual Desire in Revolutionary Russia,” Socialist Alternative, May 21, 2017 →.

Giorgio Agamben, Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life (Stanford University Press, 1998).

This is the thesis of Maria Todorova, Imagining the Balkans (Oxford University Press, 1997).

Category

Subject

A significant part of this text consists of the thoughts and ideas of my comrades and friends: Bini Adamczak, Rada Iveković, Gal Kirn, Sandro Mezzadra, Rastko Močnik, Naoki Sakai, Jon Solomon, Branimir Stojanović, Paul Stubbs, Darko Suvin, Massimiliano Tomba, and many others. I was also influenced by the exhibition “Parapolitics: Cultural Freedom and the Cold War,” HKW, Berlin (November 2017–January 2018), curated by Anselm Franke, Nida Ghouse, Paz Guevara, and Antonia Majača.