The spring sun casts warm light on a makeshift soccer field overlooked by blocks of rundown buildings. Nearby, a man in his early fifties with a slim, athletic build is leaning against a pine tree. He follows the movement of a soccer ball as it bounces between a group of young men. Every now and then, he jots down some words or sketches some images in a small notebook.

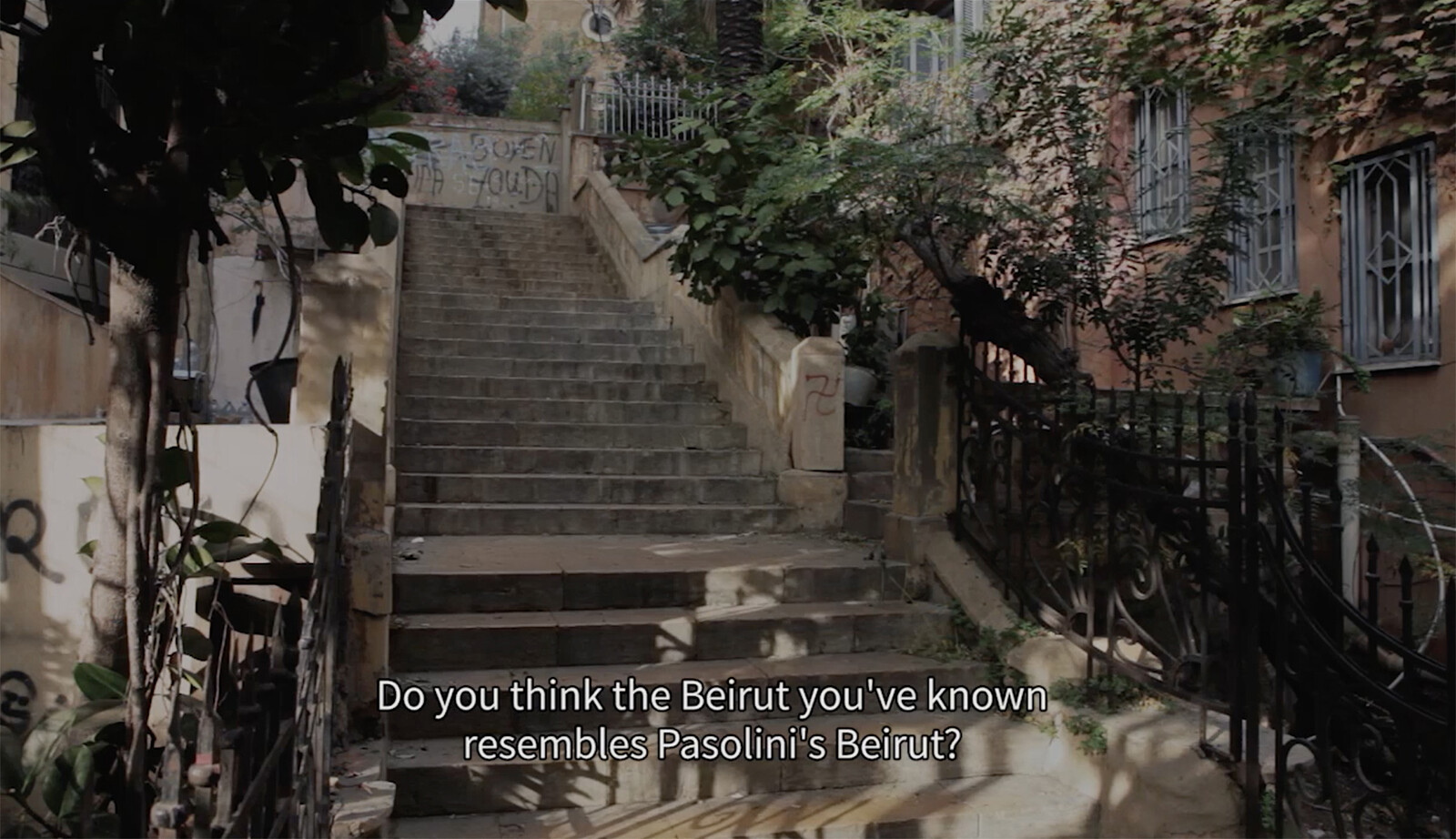

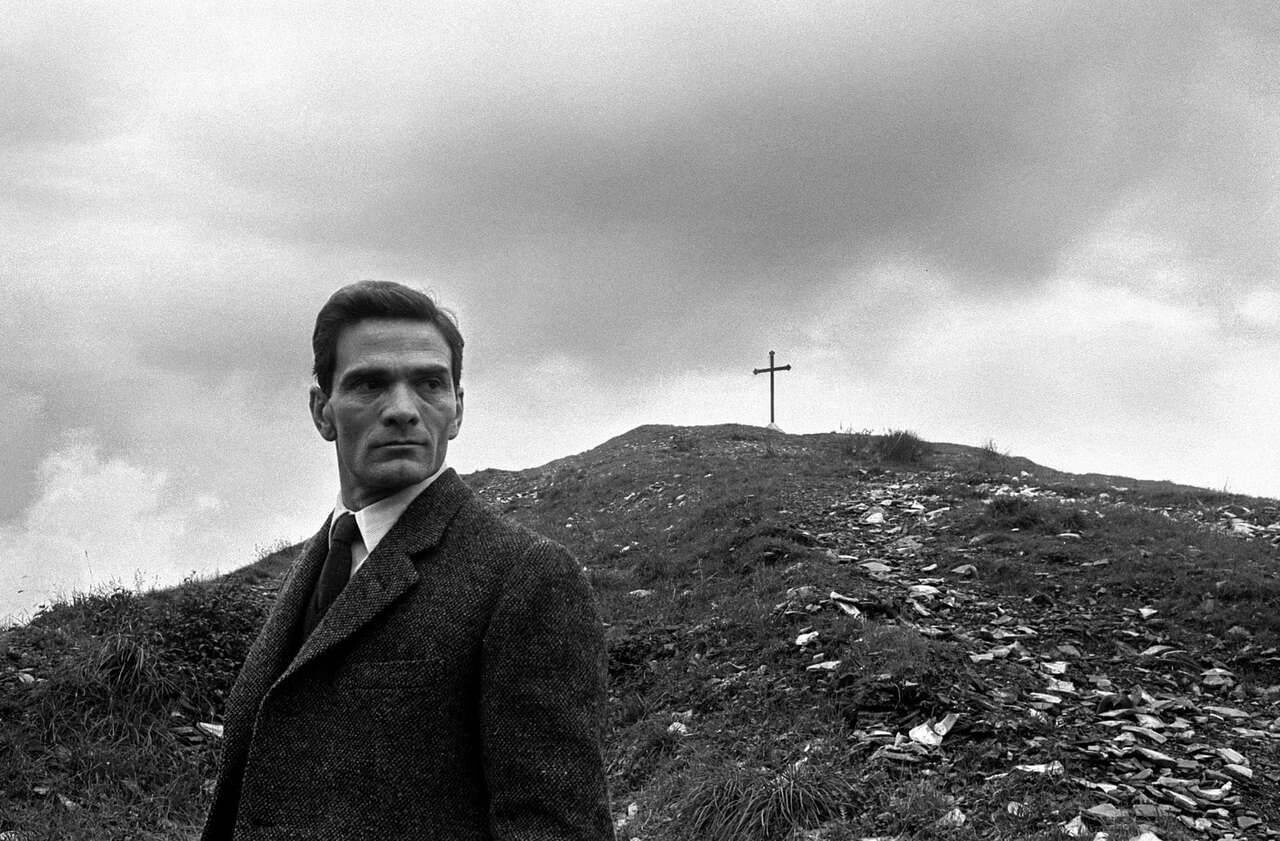

The person in this speculative scene is the Italian leftist and queer intellectual, poet, and filmmaker Pier Paolo Pasolini, whose centennial is this year. He was also known to be passionate about soccer and ephebic young men. The location could be any prewar, mid-1970s, poor neighborhood in Beirut, crowded with rural migrants looking for work in the prosperous capital. As it turns out, aside from such fantasized visions, Pasolini did indeed visit Beirut in May 1974. He spent forty-eight hours in the Lebanese capital and screened three of his films: Oedipus Rex (1967), Medea (1969), and Pigsty (1969).1 These poetic works express Pasolini’s fascination with sacredness in premodern times as well as his staunch criticism of the dehumanizing effects of capitalism on Western societies. At the time, those ideas had deep resonance in Beirut. The city was at a peak of intellectual fervor. Leftist protest movements led by labor and student unions regularly filled the streets in persistent attempts to dismantle the country’s interlinked sectarian and capitalistic structures, and to erect in their place a system of social and economic justice. In those days, marked by decolonial awakenings and the end of the Vietnam War, popular struggle in Beirut was decidedly anti-imperialist and in harmony with the general atmosphere of international solidarity with oppressed peoples everywhere. The predominant mobilizing issue, politically and culturally, was Palestine—a cause that deeply fractured Lebanese society.

Uncovering Pasolini’s brief visit to Beirut and processing its memory have provoked in me an irremediable feeling of loss. It is a double loss: that of an idiosyncratic rebel poet who envisaged the world differently, and of a city that was once an incubator for progressive ideas and affects. In an uncanny twist of fate, both Pasolini and Beirut suffered fatal violence the year after his visit. It was as if both became connected by osmosis to their tragic, concurrent destinies. In April 1975, Beirut began a vertiginous descent into a spiral of civil violence when local and regional tensions and contradictions became unmanageable. The war, which went on to last fifteen more years, destroyed many lives and entire neighborhoods. It also brought a period of cultural and political effervescence to an abrupt, enduring end. In November of that same year, Pasolini was brutally assassinated under mysterious circumstances in Ostia, a seaside town near Rome. Allegedly, he was the victim of one of his frequent sexual adventures with young, underprivileged men. Many threads of evidence suggest, however, that the killing was political, motivated by Pasolini’s critical stance towards the political class’s collusions with the economic elite during those turbulent times in Italy.2

Years ago in my own life, an Italian man in Beirut with whom I shared a love story and a passion for cinema told me he had read somewhere in passing that Pasolini had visited the city. This led me to gradually discover several threads and documents related to the poet’s encounter with Beirut. Preserved at an archive in Italy and in local Lebanese newspapers were an invitation letter, a brochure, and a couple of short articles. Eventually, I also found and recorded an oral history account that further animated the memory of the visit. This material, which had never been examined before (as far as I know), was very suggestive. I looked to the archive for its generative and radical potential as an “oracle to be consulted” to forge “weapons for the future.”3 But I found many “silences” and vanished or destroyed traces there too. These gaps sparked an impulse to fill them with moments imagined through a queer, speculative lens. In thinking history outside the limits of archival records, I have been inspired by Audre Lorde’s invitation to resort to the erotic as a “resource” rooted in a “deeply female and spiritual plane.”4 For Lorde, a Black feminist civil rights activist, the erotic is a creative energy that women possess in them, and a source of historical, political, and spiritual power and knowledge if it can be liberated from suppression by a male-dominated world order.5 Even as a queer male writer, I am moved by this sensual, feminine, erotic feeling within me to experience a deep connection across time with Pasolini’s presence in Beirut.

Beyond investigating the visit itself, my desire is to return to the first half of the 1970s as the locus of a lost golden era of leftist social and political struggles in Lebanon. By looking deeply into this time while shifting our focus toward eroticism and sexuality, can we unsettle the way protest and dissent have been engrained in our collective conscience through masculinist tropes of courage and defiance? These questions are primarily addressed to Lebanese and to Arabs more generally; think of how deeply the visual representation of resistance from that period is saturated with male militant fighters. Mainstream historical accounts have long held that the sexual revolution and subsequent gay rights movements started in the 1960s in the US and Europe. What if we imagined Beirut as the heart of a queer revolution where anti-imperialist ideals and sexual freedoms are tightly interlinked? What would happen if we imagined, further, that this was an all-encompassing revolution for “the wretched of the earth”—one that sought a definitive break with Western, capitalist, heteropatriarchal ideologies and drew inspiration from premodern spiritual wisdoms? Pasolini, a colossal figure at the nexus of queer sexuality and radical leftist politics, could help us reconfigure the past along these lines and envision alternate futures.

Before delving into speculation, the material traces of the visit merit a close look. The first meaningful document I found is a typewritten letter addressed to Pasolini and written in French by Samia Tutunji, herself a poet and prominent cultural personality in Beirut.6 In the January 1973 letter, now preserved at the Archivio Contemporaneo in Florence, Tutunji confirms Dar el Fan (House of Art)’s intention to dedicate a week to the exhibition of three or four of Pasolini’s films, and reiterates an invitation to fly in and host the Italian director. She assures him that the films could be sent in a diplomatic bag by the Lebanese embassy in Rome to avoid obstacles at customs. The status of the cultural center, Dar el Fan, which was “not officially a movie theater,” would also shield the screened films from the eyes and scissors of censors.7 According to the letter, Pasolini was expected in Beirut in October or November 1973. It’s not clear why the trip was postponed until the spring of the next year. My hunch is that the change in plans was due to the sudden eruption of the Yom Kippur War between Israel, Egypt, and Syria, which had devastating consequences for the entire region. Tutunji ends her letter with the following words: “Be assured that we will do our best to make your stay in Lebanon pleasant and fruitful for Lebanese and Arab cinema.”

Another letter, from February 1970, reveals earlier attempts to hold a Beirut screening of Medea, and to invite the director along with Maria Callas, the renowned soprano who played the lead in the film.8 Additionally, the letter carries a notably ominous tone and complains about major internal and international problems facing Lebanon—a situation that has never ceased to be relevant. “For Lebanon, currently experiencing a political conjunction immobilizing tourism,” writes Robert Misk on behalf of Mouvement Social, “your presence and that of Madame Callas would constitute a cultural manifestation but also an ‘event’ consolidating the friendship that unites our countries.” The letter ends with an assertion of hope and a belief that international solidarity can save Lebanon from imminent dangers, “a je ne sais quoi … that can flatten obstacles by reducing frontiers and humanizing contacts.” A letter from the Italian Cultural Institute in Beirut was sent a few days later in support of the invitation. Its author attempts to entice Pasolini by inviting him to visit Baalbek, “one of the most beautiful archeological sites in the world and full of ‘ideas’ that could spark your [Pasolini’s] artistic interests.”9 As the archive in Florence holds only letters written to Pasolini, these documents emanate an eerie absence of replies. Did he consider accepting the invitation? What if he had visited Lebanon then? Would he have been inspired by the majesty of Baalbek’s ancient Roman temples and considered making a film there, as he did in Aleppo’s citadel in Syria for Medea—or in Palestine, Yemen, and Morocco for other projects?

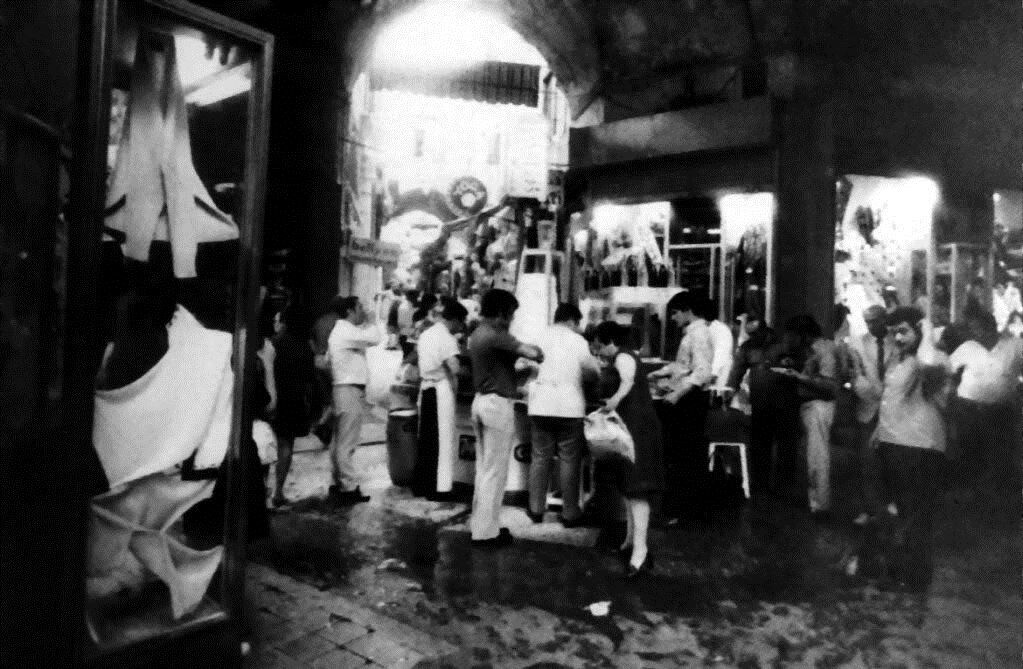

What I do know is that Pasolini’s senses were once aroused in Beirut. I found a manuscript for an article titled “The Pastries of Beirut” about the aftermath of the Israeli raid on the Lebanese airport that destroyed thirteen airplanes in December 1968.10 In it, the poet expresses his belief that Arabs and Israelis could live in peace—a utopian idea that remains, according to him, “the only possible pragmatic solution.” He argues begrudgingly that the conflict will be eventually driven by international financial interests and not nationalistic impulses, speculating over a future where Arabs and Israelis are united as producers and consumers. After a couple of paragraphs, Pasolini’s poetic language begins to emerge between the lines of political analysis. “What a marvelous smell of pastries there was in Beirut a few nights ago,” he writes. He describes his desire to try the Arab desserts beautifully displayed in the shop windows of the souk, even if he says he knew he shouldn’t eat them for “hygienic reasons.”11 “In the air, with their smell,” he adds, “there is a simple and inexplicable desire to live: to make love, not war!” The article ends on a foreboding note: “How lukewarm and sweet, although sinister, was the air of the evening in Beirut!” This document clearly reveals that Pasolini was in Beirut in March 1969, days or weeks before shooting Medea. Maybe he just passed through the city en route to scout film locations in Cappadocia or Aleppo.

Little is known from Pasolini’s later trip of his sentiments about Beirut, and his intellectual and affective connections with its people. An interview with the filmmaker for Télé Liban would have elicited some clues.12 But during the civil war, the film rolls it was recorded on were destroyed along with much of the Lebanese national television network’s archive. A year and a half ago, I was able to contact Fouad Naim, the journalist who interviewed Pasolini in 1974. Naim, who was also a painter, actor, and theater director, said that he didn’t remember anything from the encounter. “It’s unforgivable but it’s like that,” he wrote to me in French in a WhatsApp message. “I am infinitely sorry.”

Dar el Fan, the space that hosted Pasolini and the audiences who saw his films, was also destroyed shortly after the civil war started.13 We cannot know if that public was impressed, intrigued, inspired, or offended by the three screenings. The building was located in Ras el Nabeh, a neighborhood in central Beirut close to the war-era line of demarcation. Dar el Fan was an exceptional institution, politically and prolifically central to Beirut’s cultural dynamism.14 Since much of the organization’s archive perished under the rubble, I was surprised to find one of the surviving brochures for its ciné-club de Beyrouth on the other side of the Mediterranean, at the Florence archive.15 Pasolini must have carried that copy with him as he left Beirut. Its cover shows miniature drawings of wrestlers in a variety of homoerotic positions taken from an ancient tomb in Egypt. The brochure contains several articles about cinema, including one that sells the merits of establishing a cinémathèque in Beirut, where films would satisfy their “hard desire to last.” It ends with a catalogue of the film titles screened by the ciné-club between 1957 and 1971—an impressive list of world cinema that includes Kurosawa’s Rashomon, Varda’s Lion’s Heart, and Cassavetes’s Shadows.

Beyond physical documents, I was fortunate to find one substantial trail of oral history in relation to the visit. Simone Fattal, a Lebanese artist, told me that she had lunch with Pasolini at Tuntunji’s house. She recalled that Persian rice—cooked “very well”—was served.16 (Tuntunji’s parents had been ambassadors to Iran and hired a local cook.) She said that Etel Adnan, Fattal’s longtime partner, was also among those present. “At the end of the lunch—I don’t know how—music was played and because I can’t resist music, I got up and danced,” she wrote to me, stressing that she performed a belly dance. She also remembered that at some point, Pasolini removed himself from the conversation and went into the kitchen. In some iterations of my fantasized itinerary, the filmmaker’s adventures in Beirut take a wild turn after that lunch.

In the kitchen, Pasolini meets a young man, maybe Tutunji’s driver or gardener. They communicate through body language. Pasolini sneaks out with him to go for a ride around his neighborhood. Once there, he recognizes “the refuse and odor of poverty” of the borgate romane, the lower-class areas of the urban-rural fringes of Rome.17 Here, in this poor part of Beirut, he feels liberated from the limelight. He sees a group of boys “light as rags” playing soccer “with juvenile thoughtlessness.”18 He rolls up his sleeves and joins them. Breathless, he stops after a little while. He leans against a nearby pine tree and pulls his red notebook from his pocket. He starts writing a poem. He recalls the ecstatic and humble feelings of the “intoxicated adolescent symbiosis of sex and death” that he once felt in his early years in Rome.19

When I first visited the Florence archive, one of the archivists told me privately that Pasolini had a small notebook with him in Beirut where he wrote down words in Arabic. I imagined that they were poetic terms he gathered and used to flirt with Lebanese men. Maybe the notebook also contained his thoughts about the city and its people. Maybe there were improvised drawings and poems in it. I never saw the notebook (allegedly kept secret by Pasolini’s niece and heir), and my recent inquiries about it failed too.

Even though the notebook is hidden, fragments of Pasolini’s voice can be gleaned from short articles in local Lebanese newspapers. Upon his arrival to Beirut on the evening of Friday, May 3, a group of journalists intercept him with a provocative question about his seemingly contradictory adherence to both Catholicism and Marxism. At the source of the confusion is Pasolini’s Teorema (1968), a messianic film that shows the collapse of a bourgeois family in Northern Italy caused by the enigmatic visit of a charismatic young man. At first, Pasolini appears amused by the question. He laughs, raises his arms, and says: “Oh God! But that’s magnificent! What a liberation!” But then he adds that he was only joking and asserts his atheism.20 Speaking in French, he says that he was “very interested in mysticism” but not in organized religions. He calls “dreaming art” a religious act that’s more important than the actual realization of works of art, which he describes as a mundane social activity. He also proclaims that he is decidedly a Marxist but is independent from any political party. Further down in one of the articles, Pasolini expresses his dismay that his most recent film, Arabian Nights (1974), will not be screened in Arab countries because of its unbridled look at premodern sexualities in the Arab region. He says that the film took a political stance against consumerism in big Italian cities, something he despised. “A horrible, horrible civilization,” he says, in reference to contemporary Western societies. “Yes, I made a political film because the question of sex is a political question. If it was to be screened in Lebanon, uncensored … it would be a form of a political revolution.”21

I see Pasolini’s call for a sexual revolution as an invitation to revisit that period when sex and politics were deeply intertwined. Contemporary scholars like Emily K. Hobson, a historian of radicalism, sexuality, and race, have established solid links between struggles for sexual self-determination and the revolutionary internationalism of the 1970s.22 Others, like Todd Shepard, a historian who studies the “end of empires,” contend that Arab immigrants, as racialized others during the postcolonial period, were essential to the sexual revolution in Europe.23 And some, like Jarrod Hayes, whose research interests include postcolonial and LGBTQ studies, look at instances of anti-colonial resistance in 1950s Algeria as forms of queer defiance of colonial heterosexuality.24 I believe that rethinking the nature, ontology, and history of homosexual liberation in connection with anti-imperialist leftist struggles could help us grasp the potential of queerness as a force of social and political change in a place like Beirut in the 1970s.

For political and intellectual historian Joseph Massad, the roots of the gay movement in Lebanon and the Arab region date to the 1990s when gay Western organizations waged an aggressive campaign to transform Arab men and women “from practitioners of same-sex contact into subjects who identify as ‘homosexual’ and ‘gay.’”25 Others, like Ghassan Makarem, one of the founders of the first Lebanese LGBT rights organization Helem (Dream), challenge this lopsided historical account. Makarem situates the founding mission of Helem in relation to international movements for social justice and shows, for example, how gay activists were deeply involved, from the early 2000s on, in protesting Israeli assaults on Palestinians and the US invasion of Iraq.26 What if we stretch these more recent histories back again to the 1960s and ’70s? Rather than thinking along identitarian lines, what if we think of queerness as an “insistence on potentiality and concrete possibility for another world,” to borrow from queer theorist José Esteban Muñoz?27 The queer people I have spoken with who lived in Beirut in the 1970s relate that homosexuality was kept a private matter. Beyond public visibility, then, we can focus the historical lens on how aspects of queerness oriented queer activists in the environment around them, how it fueled their ideologies, their alliances and activism in social and political arenas.

After the screening of Oedipus Rex at Dar el Fan, Pasolini notices a handsome young man staring at him. The cinephile is overexcited to see his idol in the flesh. They exchange intense looks and end up drinking wine in the director’s hotel room. Between moments of intimacy, they talk about radical beginnings for a postcapitalist world. The young man, who comes from a working-class family, studies political science at the Lebanese University and is an activist in the student movement. Lately, he has been organizing protests in support of factory workers. He tells Pasolini about calls for a third-world gay revolution in New York and about the Homosexual Front for Revolutionary Action (FHAR) in Paris writing statements of solidarity with Algerian migrant workers.28 His vision is to create a grassroots queer movement inspired by the Arab region’s rich and diverse histories of sexuality, one that would champion the causes of laborers and peasants. Pasolini is reticent. He no longer believes in revolution, but “cannot help but be on the side of the young who are fighting for it.”29 He mentions his plan to make a film called Porno-Teo-Kolossal that would reinterpret the biblical myth of Sodom. In his fantasized queer utopian city, homosexuality is the norm, and there is “the most absolute” freedom for minorities (heterosexuals, for example, but also Black, Jewish, and “gypsy” minorities …).30 Every year a “fecundity festival” ensures the perpetuation of human life. As loyal citizens, gay men and women fornicate in one big orgy. Pasolini says that he based this vision of Sodom on Rome in the 1950s where, he says, he strangely experienced more sexual freedom than he did after the sexual revolution of later decades. The story, he adds, ends on a catastrophic note. The hospitality of the city is stretched to its limits by a group of proto-fascists and Sodom perishes under a rain of brimstone and fire.

Even though he is considered a major queer icon today, Pasolini was very critical towards the gay liberation movement. As art historian Ara H. Merjian explains, Pasolini anticipated that “the incorporation of marginalized identities to society’s representational regime … would hasten their commodification.”31 Patrick Rumble, a film scholar specializing in Italian cinema, also argues that the Italian intellectual was very skeptical of new forms of tolerance towards sexual difference in the West; he quotes Pasolini as asserting that this tolerance was imposed “from above” and aimed at turning individuals into “good consumers.” He writes that Pasolini saw his own homosexuality in opposition to impulses towards conformity with a new heteronormative order, as a form of rupture and discontinuity and as “the apocalypse that massacred all categories.”32 His celebration of the unruliness of sexuality is clear in his film Arabian Nights, where he aptly attacks modern Western epistemologies of bodies and desire and reveals his fascination with the Arab region.

In fact, Pasolini saw in what was then called the Orient “a roomy place full of possibility” away from the denaturalization and alienation of Western cultures.33 According to film and gender scholar Daniel Humphrey, Pasolini’s fetishizing of the Orient and his eroticizing gaze on Africans and Arabs in several feature films and documentaries should be seen as auto-critical ethnographic endeavors where the filmmaker questions his own eurocentrism. Based on his reading of Edward Said, Humphrey suggests the term “queer Orientalism” to describe Pasolini’s desire for Morocco or Yemen, one that materializes on the faces and bodies he recorded.34 Scholar Luca Caminati, whose research deals with postcolonial theory in Italian cinema and media, also considers the filmmaker’s fascination with the elsewhere, specifically the Third World, and sees it “not as escape but rather as possible political alterity” to Western progress.35 He groups Pasolini with Genet, Sartre, and other European Marxists for their involvement throughout the 1950s and ’60s “in articulating a form of transnational revolutionary universalism.”36

Pasolini’s work creates a queer space of possibility—a place for stories and histories yet untold. In the last part of Porno-Teo-Kolossal, Pasolini offers an alternative to his dystopian images of a European continent destroyed by “capitalistic homologation and cultural genocide.”37 This section of the script is set in Ur (a prefix that could mean archaic), a hypothetical city located somewhere in Mesopotamia, modern-day Iraq. Pasolini imagines the epic voyage of his main character, Epifanio, from north to south—in what today feels like a counterpoint to the recent waves of perilous migration towards Europe. Witnessing European workers becoming petit bourgeois in his lifetime, Pasolini believed that emancipation could come only from African migrants, the new sotto-proletariat.38 But he feared that even his cherished Orient, where old and new cohabitated, would eventually capitulate to modernity. In Ur, Epifanio meets a “short Arab” selling medals and souvenirs. He intimates to him that the Messiah was indeed born in these lands, but a lot of time has passed and he is now dead and forgotten. Upon realizing that he is “irremediably late,” Epifanio dies.39 The end of the film offers no clear conclusion. In the afterlife, Epifanio is pictured waiting indefinitely for something to happen. Resisting teleological resolution, Pasolini, who was increasingly interested in experimenting with new forms, imagined this scene to be an “infinite sequence shot.”40

Did he witness the “rebirth of a myth” while watching the “wretched enjoy the evening” in the poor neighborhoods of Beirut? Or did these lines resonate again: “But I with the conscious heart of one who can live only in history, will I ever again be able to act with pure passion when I know that history is over?”41 The unbearable postmortem images of Pasolini’s disfigured face loom over a cruel world that allowed the destruction of a body he chose to throw “into the struggle,” just as another destructive explosion in Beirut piles up new “wreckage upon wreckage.”42 Maybe there is solace in the perduring beauty of Pasolini’s poems, just as more recent loud chants continue to resonate from Lebanese queer activists demanding the end of patriarchal control.43

S. N., “Pasolini in Beirut: More Important than Realizing the Work Is Dreaming It,” Annahar Newspaper (Beirut), May 4, 1974.

Ed Vulliamy, “Who Really Killed Pier Paolo Pasolini?” The Guardian, August 23, 2014 →.

Nick Denes writing on Raoul-Jean Moulin, quoted in Anthony Downey, “Contingency, Dissonance and Performativity: Critical Archives and Knowledge Production in Contemporary Art,” in Dissonant Archives: Contemporary Visual Culture and Contested Narratives in the Middle East, ed. Anthony Downey (IBTauris, 2015), 30.

Audre Lorde, Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches (Crossing Press, 1984), 53.

Lorde, Sister Outsider, 54, 55.

Letter from Samia Tutunji to Pier Paolo Pasolini, January 5, 1973, IT ACGV PPP.I.1179. 1, Archivio Contemporaneo Bonsanti, Florence, Italy. Unless noted otherwise, all excerpts from the archival documents and articles have been translated from Arabic, French, and Italian by me.

To this day, Lebanese filmmakers and distributors continue to fight against censorship of films imposed by religious and political interests and enforced by Lebanese security officials.

The invitation came from the Mouvement Social, a social and political organization founded by a priest and still active to this day. Letter from Robert Misk from the Mouvement Social to Pier Paolo Pasolini, February 19, 1970, IT ACGV PPP.I.1213. 2(a-c)/b, Archivio Contemporaneo Bonsanti.

Letter from the Italian Cultural Institute in Beirut to Pier Paolo Pasolini, February 24, 1970, IT ACGV PPP.I.1213. 2(a-c)/c, Archivio Contemporaneo Bonsanti.

Manuscript for an article entitled “Mostri e mostriciattoli. Beyruth. Mercks. I donatori di sangue,” May 1, 1969, IT ACGV PPP.II.1.145. 37, Archivio Contemporaneo Bonsanti. The archive mentions that the article was published in Tempo 31, no. 19 (May 10, 1969) with a slightly different title: “Mostri e mostriciattoli. I pasticcini di Beirut. La faccia di Merckx. Donatori di sangue.”

The souks of downtown Beirut, the popular heart of the city, were destroyed during the civil war. In the 1990s, they were privatized and rebuilt with fancy stores selling expensive international brands.

Télé Liban became Lebanon’s first public television network in 1959.

Janine Rubeiz et Dar el Fan: Regard vers un patrimoine culturel (Beirut: Dar Annahar Press, 2003), 23.

Janine Rubeiz et Dar el Fan, 29. Founded in 1967 by Janine Rubeiz, an “enlightened” bourgeois socialite, the center programmed, over a period of eight years, 240 conferences and debates, sixty poetry nights, ninety exhibitions, and 150 film screenings from different parts of the world. A 1972 manifesto makes clear the humanistic approach of Dar el Fan, describing its mission as “political engagement” with historical events considered as lived experiences that recognize “the suffering, the expectation, and the hope” of the Other.

Original brochure of the Ciné-Club of Beirut, May 3, 1974, IT ACGV PPP.V.3.213. 70, Archivio Contemporaneo Bonsanti.

Simone Fattal, email to the author, September 27, 2020.

The reference is from Pasolini’s poem “The Ashes of Gramsci,” in Pier Paolo Pasolini, Pier Paolo Pasolini: Poems, trans. Norman MacAfee (Noonday Press, 1996), 23. In 1949, Pasolini fled his native Friuli with his mother and settled in Rome after being accused of “obscene acts” with minors in public. Even though he was acquitted, he lost his job as a teacher and was removed from the Communist Party (see Ian Thomson, “Pier Paolo Pasolini: No Saint,” The Guardian, February 22, 2013 →.) It was in the borgate that he found his first cinematic inspirations crystalized in Accatone (1961) and Mamma Roma (1962). There, he also discovered the ragazzi and a violent homosexual world that would bring him both “fortune and fate.” This is according to his friend and renowned Italian writer Alberto Moravia, interviewed after Pasolini’s assassination in Those Who Tell the Truth Shall Die, a 1981 documentary by Philo Bregstein.

Pier Paolo Pasolini: Poems, 21.

Pier Paolo Pasolini: Poems, 9.

S. N., “Pasolini à Beyrouth: “Rêver c’est une forme de religiosité,” L’Orient le Jour (Beirut), May 5, 1974.

S. N., “Pasolini in Beirut: More Important than Realizing the Work Is Dreaming It.”

Emily K. Hobson, Lavender and Red: Liberation and Solidarity in the Gay and Lesbian Left (University of California Press, 2016).

Todd Shepard, Sex, France, and Arab Men, 1962–1979 (University of Chicago Press, 2017).

Jarrod Hayes, “Queer Resistance to (Neo-)colonialism in Algeria,” in Postcolonial, Queer: Theoretical Intersections, ed. John C. Hawley and Dennis Altman (SUNY Press, 2001).

Joseph Massad, Desiring Arabs (University of Chicago Press, 2007), 162.

Ghassan Makarem, “The Story of HELEM,” Journal of Middle East Women’s Studies 7, no. 3 (2011): 98, 102.

José Esteban Muñoz, Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity (NYU Press, 2009), 1.

Inspired by the call for “a third-world gay revolution” (a term used to include Black people, Latin Americans, and all other peoples of color) that appeared in a gay publication in New York in the early 1970s. “T.W.G.R.: Third World Gay Revolution,” Come Out! A Liberation Forum for the Gay Community 1, no. 5 (September–October 1970), 12.

A statement that Pasolini made in an interview published by the French newspaper Le Monde on February 26, 1971 as mentioned in Enzo Siciliano, foreword to Pier Paolo Pasolini: Poems, xiv.

Porno-Teo-Kolossal is a film that Pasolini wrote but never realized. Information from the script is based on Julie Paquette, “From Capitalist Development to the Endless Sequence Shot: The Four ‘Utopias’ of Porno-Teo-Kolossal,” Cinémas 27, no. 1 (2016): 99. Paquette’s essay provides extensive details of the script, including the following excerpt (in French): “Non seulement des minorités hétérosexuelles, mais aussi des minorités noires, des minorités juives, des minorités tzigane, qui vivent ici dans la liberté la plus absolue, y compris intérieure … Sodome, … tout est fondé sur un sens réel de la démocratie.”

Ara H. Merjian, Against the Avant-Garde: Pier Paolo Pasolini, Contemporary Art, and Neocapitalism (University of Chicago Press, 2020), 214–15.

Patrick Allen Rumble, Allegories of Contamination: Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Trilogy of Life (University of Toronto Press, 1996), 135, 140.

Daniel Humphrey, Archaic Modernism: Queer Poetics in the Cinema of Pier Paolo Pasolini (Wayne State University Press, 2020), 108.

Humphrey, Archaic Modernism, 108.

Luca Caminati, “Notes for a Revolution: Pasolini’s Postcolonial Essay Films,” in The Essay Film: Dialogue, Politics, Utopia, ed. Elizabeth A. Papazian and Caroline Eades (Columbia University Press/Wallflower, 2016), 131.

Caminati, “Notes for a Revolution,” 133.

Paquette, “From Capitalist Development,” 107.

Paquette, “From Capitalist Development,” 106.

Paquette, “From Capitalist Development,” 106.

Paquette, “From Capitalist Development,” 111.

The last lines of “The Ashes of Gramsci,” in Pier Paolo Pasolini: Poems, 23.

Reference from a posthumous Pasolini manuscript mentioned in Pier Paolo Pasolini: Poems, xi. The second reference is from Walter Benjamin’s 1940 essay Theses on the Philosophy of History.

See Rasha Younes, “‘If Not Now, When?’ Queer and Trans People Reclaim Their Power in Lebanon’s Revolution,” Human Rights Watch, May 7, 2020 →.