Continued from “What We Talk about When We Talk about Crisis: A Conversation, Part 1”

Marwa Arsanios: I would like to pick up our conversation from where we left it in the first part, with the question of “crisis.”

Yazan Khalili: In Janet Roitman’s book Anti-Crisis the term “crisis” is criticized as an overused term, and yet somehow it has no basis or clear meaning anymore; one can say that everything is a crisis all the time. Like, what is not a crisis these days? In the cultural sector we operate as if we are always functioning under crisis, or trying to avoid a crisis. A hovering crisis.

And where is the crisis? How do we catch it? How do we understand it? How do we put our hands on it to be able to really analyze it?

MA: The way I think about the so-called crisis of the arts or of culture is that it is related to certain mechanisms that are side effects of a political and economic situation, which limit the parameters of what culture can be. For example, we talked in our previous conversation about the “NGO-ification” of culture and its depoliticization. But maybe we could ask: What is the state of noncrisis for the cultural institution?

YK: Exactly. What is a noncrisis?

MA: The state of noncrisis is claimed by the Western, publicly funded institution that is producing what it is expected to produce.

Lara Khaldi: Yes, a stable institution in a place where the politics are fairly stable. Where the public funding is steady. Or with an image that is stable, because public funding is often cut in Europe when there’s a change of government or a political crisis as well.

MA: Exactly, and it is an institution that is constantly and regularly producing and reproducing itself at the same rhythm. Without having to re-question its meaning in depth. But we should not forget that there is always a looming threat that public funding will be cut—right-wing governments try to take it away as soon as they are elected, or it is cut for other political reasons when an institution is “canceled” because of its program or a political position it has taken.

YK: Yes, state funding for arts and culture also becomes a tool of political struggle when there are shifts in the power structure, which also makes institutions totally dependent on state funding and vulnerable without any alternatives. Of course, we are not here to say that the state should withdraw funding from art and culture, but that the state isn’t a steady structure that we should always take for granted.

In a way, crisis then becomes a kind of essential reason to question existing structures. If noncrisis is being steady and certain, then crisis is about uncertainty. Crisis produces the moment when the institution has to face itself and to decide to make a radical and extreme decision about its structures, its vision and mission, and its programs.

LK: But the presence of this imminent crisis is very steady for institutions in our region, which are always in that state. It’s usually connected to funding, either the threat of losing funding or not knowing where funding will come from in a year or a few months. So instead of thinking of other ways to fund culture, for example, the crisis continues, and looking for funding in the same ways continues. The institution reproduces itself through the crisis.

YK: This is a very important point: the invisible violence of funding, not only the current funding that the institution has, but the future funding that it doesn’t have yet, with no guarantees that it will get. Many of our cultural institutions, and I would say most of the cultural economy in our region, are based on international funding, which responds to a certain kind of crisis, while some depend on private funding by philanthropists. They usually end up spending their budgets on huge buildings and falling into the same financial crisis again. The institution always has to be in crisis to be able to overcome the crisis. It’s an infrastructural crisis that the cultural institution is based on.

I’ll tell you a story. A friend once told me she was in a meeting with a group of different institutions and a donor. She said to the donor: “We are tired of this, we don’t want your funding anymore.” And then one of the directors of another institution told the donor: “See, if you don’t give us funding, look how people will feel.”

The crisis becomes a wheel that allows certain funding to come in, to either reduce tensions or reduce the possibility of change. Crisis plays a double role; it opens the possibility of change and closes it at the same time. It makes us understand that there is something wrong in the structure, but it also puts us in an existential dilemma, a real fear of witnessing the collapse of the institution and the jobs it provides. It is essential to think about how institutions, governments, and power structures use crisis to pass more regulations and more cuts and changes to existing structures—we need to think of crisis as an opportunity that can be used by many sides, and the question is who is ready to seize the moment.

MA: And of course crisis is a state of being on different governmental levels. It’s rooted in the economy and it trickles down to cultural institutions. It is often considered a problem of management or governance rather than a serious structural and infrastructural issue.

LK: It’s double for these institutions, because you have the bigger crisis outside of the institution and the inner crisis of the institution. A few years ago, I was in a donor meeting with different cultural institutions from Palestine and an international donor. This international donor was thinking about increasing the funds for the Palestinian cultural sector. We were invited to this meeting to provide arguments to the donor to convince their government to increase the fund. And one of the employees of a mainstream Palestinian cultural institution argued that if they didn’t increase budgets, then young people would become more extremist: more religious, and also more violent. As if culture were a space that is neutral and would save these young people from their cultural surroundings. Of course he was also actually just reinstating what international funding is for in Palestine: to depoliticize.

YK: How then do we break away from this vicious circle of crisis? What does understanding a crisis offer us, in terms of practicing something beyond survival mode? When we understand that the crisis is not an exceptional event that comes from outside of the capitalist structures we are living in—that it’s already part of the movement and development of these structures? We need to start to think of the crisis in the present, not as a future event.

I think Marwa or Lara said that institutions try to claim there is a crisis to be able to get funding. I don’t think the funding itself is the crisis.

MA: I follow what you mean, about how to get out of this closed, vicious circle of the crisis economy, where one needs to be in a continuous state of crisis in order to get funding. Of course, the funding economy is not the source of the problem. I think a crisis is not only an economic mechanism, but also a discursive one. These are completely intertwined, but maybe we can try to separate the two for a second. There’s a crisis in and of language, and when we talk about the institution, we reproduce its language. This is why I was asking: What is a noncrisis? Is it possible to imagine it as a linguistic breakthrough? This could lead us to inventing new infrastructures outside the existing one. Perhaps this is what many artists already do.

YK: It is for sure discursive. Actually, in Arabic we use the word “crisis” to speak about traffic jams (أزمة سير) and heart attacks (أزمة قلبية). In Arabic it’s the word (أزمة) that is used to say that a whole structure is jammed or isn’t able to produce or move anymore. But at the same time, we know that crisis is something that is in motion all the time, and it allows radical change and imagination.

To bring in an example: At Sakakini, in 2015, we said, okay, this is a crisis. For six or seven months, we were working against the feeling that the center was going to close and we would have to go find funding immediately. We needed money. We needed to go back to the structure that we had before: to find a small fund to pay for a good writer to write a proposal, apply to a donor with a project, get money from the donor, spend the money, and then get more money. As if our crisis was that we didn’t manage to write a good proposal. It took us some time to be able to say, let’s think beyond the crisis. We have to think slowly. Let’s move to another situation that is not defined through the crisis itself.

Crisis puts you in a situation where you can only think in these binaries of crisis and noncrisis, not rethinking the whole structure.

LK: I remember that time at Sakakini. We accepted that the crisis should not stay in the background, that we should bring it to the forefront. What Marwa was saying is really important—it’s an ideological or discursive problem. It’s about how you see and frame the crisis. And I think that the issue is that the crisis is always pushed to the backstage. It’s rendered invisible inside the institution. It’s like what Yazan was saying, that this maintains a safe structure. But then to bring it to the forefront, where it becomes the project of the institution itself, is something that doesn’t happen so often. Usually it remains an administrative question rather than a cultural or artistic question, which is strange.

So, what followed at Sakakini was an attempt to change structurally, right? And that included artistic and cultural work.

MA: I think you made a really important point, Lara. Crisis is often thought about as an administrative or managerial issue, a crisis of management. We just need to change how we manage the institution rather than radically rethink what culture is. Often people want to go back to what was there before the crisis (the NGO economy), which seems like the safest place. But first of all, this is not possible. Second, these new material conditions created by the crisis have the power to push an institution to think about what kind of new artistic forms or structures are produced. A radical understanding of culture.

YK: The moment we claim that something is a crisis, some openings happen in the structure, in the order of things. These openings can be small or big, can exist for a long time or a short time. But certainly gaps happen. And then there are situations that allow people or agents to infiltrate these gaps. Or what Naomi Klein speaks about in The Shock Doctrine, where a crisis happens and then companies infiltrate society and the government imposes new rules or cuts. It’s sometimes more possible in the art sector to see individuals, groups, and collectives using these moments to infiltrate the structure that is in crisis or that claims the crisis.

But of course this is also a very materialistic moment, because who’s available then, and who has access? Who has time, who has the energy? Who is in Lebanon or in Palestine or in Egypt at that moment? It’s not abstract. Sometimes things do happen and many other times the gap just opens and closes without anyone being able to seize the chance.

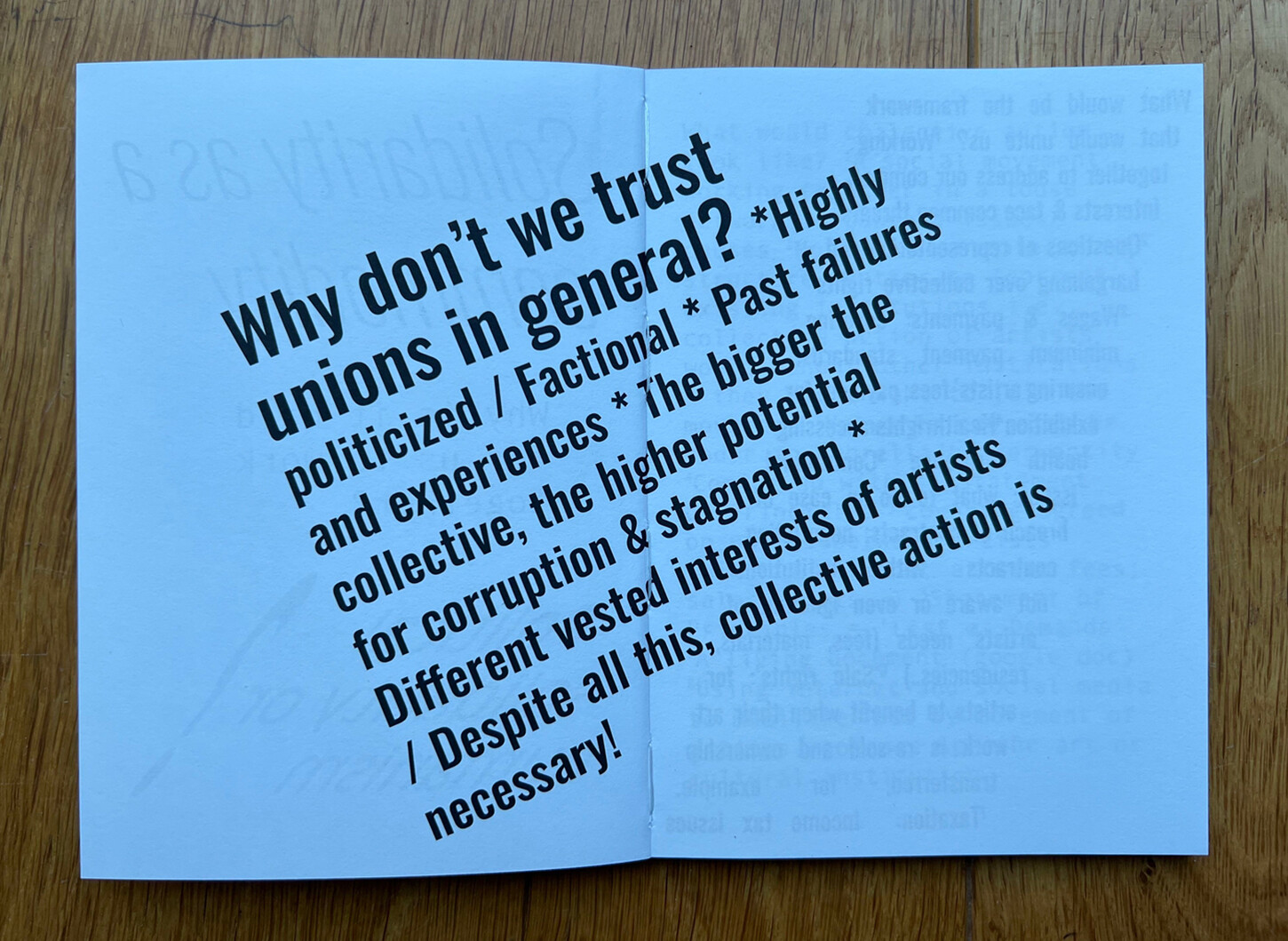

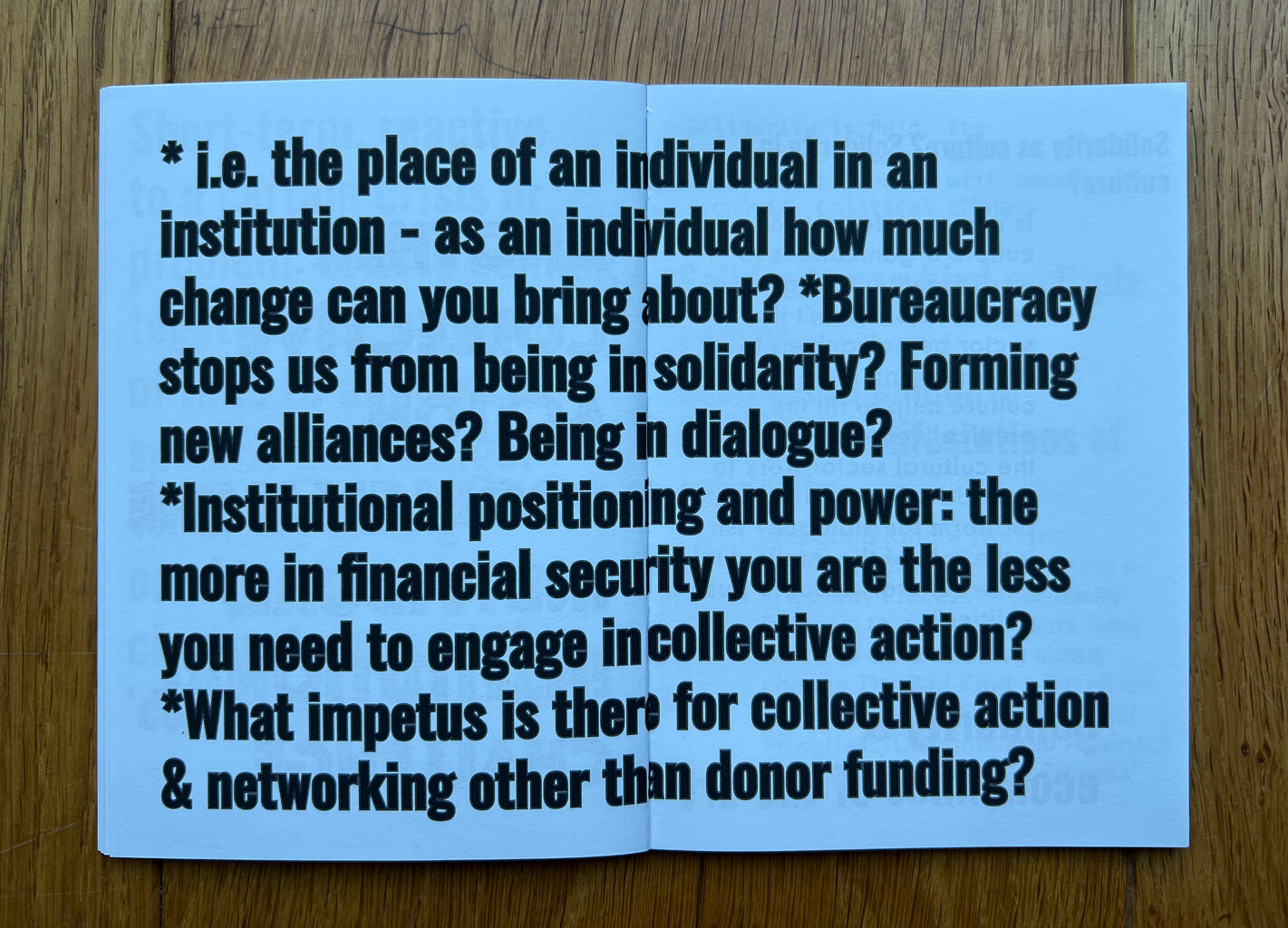

LK: Maybe we’re overusing the word “crisis.” What I’m speaking about in specific is the economic structure of the institution. Everyone knows there’s an issue that’s not being addressed. There is a fear of changing how institutions work and what they represent, and there are managerial issues with these institutions. You only hear it through gossip usually, right? The maltreatment of the team, of the practitioners. The artist fees. Now you see more and more organization around this. But usually it works through gossip, because that’s the place where the weak class in the cultural sector can speak. We have very small art and cultural scenes where the gates can close if you speak loudly. These issues are dealt with in secret. Other models of managing the cultural institution more openly require tackling it right through artistic practice. So here an artist-run institution would come in, right? Artist-run institutions are quite different from other structures because of this continuous questioning.

MA: So are we talking about more liquid structures?

YK: I think the question of the individual’s relations to institutions is very important. It’s a very big question about the economy of art institutions and the economy of art practice, requiring a kind of fluidity. You are always expected to be moving and changing. And this shift towards a more liquid institution or liquid structures, where the director stays for a few years and then rotates—I think it’s important that power does not remain as it is inside these institutions. But we should also rethink how this power moves. It’s not enough to change directors. It’s more about how these structures as a whole include individuals, and also challenge the individuals within them. We need to ask how much power people get within these institutions, and how many institutions also get power because of these people. On one hand, we have the exploitation of intellectual workers inside the gig economy. On the other hand we have these individuals who work in one institution for twenty or twenty-five years, who are super protected and secure on many levels. And securing their salary becomes our mission, the mission of the freelancers, because through us they can continue being able to get funding, etc., because of the work we do. What would these individuals do if they left their jobs? How would they secure their lives and income in a society with limited job opportunities and no social security? How do we create security not only for the few but for everyone? When we speak of fluidity, it shouldn’t mean insecurity and the gig economy.

MA: Liquidity is, as you said, something that should be worked against in many situations. And I guess this really depends on what kind of situations we’re talking about. Who gets the secure job and who stays as a freelance? I’m thinking that when these more liquid or horizontal or precarious models of institutions appear, they actually challenge the other model. A new form happens. But the problem is when these forms become fixed.

Liquidity—not in the sense of the neoliberal way of working, but more in the sense of fluid structures—is an important feature. It entails an energy for self-critique and an ability to change. As Lara was saying, this happens in artist collectives and artist-run spaces because they are so precarious. They have to adapt to every material condition around them. This can be very exhausting and very exploitative, in the sense of self-exploitation. So it’s not ideal, and not to be fetishized, but maybe a structure can be in a constant process of questioning and never become a rigid model. You always need something that is fixed and something that is moving, right? You need both of these dynamics.

LK: If an NGO’s structure works more organically, it could allow for change. I think on one hand you do need models, and the NGO is a model that kind of worked at a certain time. The problem is that it became the only model that is reproducible; that’s the paradox. So, it’s important to have something that is reproducible to get yourself out of the monoculture model of an institution. But then I agree that a structure needs to keep changing so that it doesn’t get stuck, because every structure has its issues.

So how does it keep moving? I think if we’re talking about a more organic institution, a cultural institution, then the change would be organic to the institution, because it depends on the community and what the community needs. It depends on different generations participating.

YK: Yes, I agree with Lara that it’s ironic. Marwa, you use the word “model”—maybe it’s a model on the conceptual level and not only on the procedural level, like a manual. It’s not that to move away from the crisis you do one, two, three, four, five, six, and you’re done. It’s more like, how do we begin the process of thinking?

There are many models and they move with the individuals who are part of these moments of change. These issues of scaling, of moving, of learning, of teaching, of taking the experience from one place to another, are very crucial in the lives of social movements. They are very fragile, very based on individuals putting in time and effort. They happen in a very limited time in the life of a person. When it comes to language, how do you speak about these kinds of possibilities and practices, and how do you bring them into the imagination of what’s possible? It is also important to think of how the donor economy manages to force a mono-structural type of institution, where all institutions have the same model—general assembly, board, and managerial team. When this happens, all institutions fall into the same crisis when there is a change in the economic or political situation. It is important to think of multi-structures, different models that can engage with the crisis in different ways. Like in environmental agriculture, multi-crop agriculture can survive a disease better than monoculture.

LK: In terms of museums in Palestine, I look at the way the Palestinian Museum responds or works with the community and helps it maintain a relation to the status quo. Museums are building this kind of narrative of being community builders—but why start an institution and then build a community around it? It’s a very simple question. Thinking more about that, I’m curious how the community changes the museum. Museums will be changed, because cultural institutions belong to the people. But change is about the moment when people take them over.

A great example is this small museum on the campus of Al Quds University. It’s called the Abu Jihad Museum, also known as the “prisoners’ museum.” It’s a museum dedicated to Palestinian political prisoners and detainees. And a big part of it is a classical museum, where you have information about the prisoners, a historical perspective, stories from prison, and objects made by prisoners. This is for the student audience. But students don’t go there because students usually have a family member or a friend who’s actually detained, or they have been detained themselves. So they have first-hand experience. But what is quite interesting in this museum is that the community of the former political prisoners took an interest in it. And the lawyers of former political prisoners started using the museum for its archive of official documents and letters of former prisoners. So the archive has become extremely useful for the community. In a sense the community has changed the institution and has given it a completely different reason for being. It’s necessary that this institution remains, and not because of the four visitors who come to see the exhibitions, but because it’s being used by the community itself. The archive is a politically active archive.

YK: How do you change the audience? I think that’s what we tried to do at Sakakini, shifting it from a spectator audience to a producer audience. The goal is not to change the audience as such, but to change the institution’s understanding of the audience. The audience is made up of those people who utilize the institution. This is the community. It’s not the people who come to attend events or do workshops; it’s the people who put on the workshops, who use the facilities, the legal structure, the administrative structure, the equipment, the spaces. In five years at Sakakini, we tried to make a shift in the way that we understood our relation to the community. The community utilizes and produces the center itself. This is close to what Lara was saying about the Abu Jihad Museum.

MA: I think these are two great examples, which also link back to what we were saying before in terms of the model and its reproducibility. What both of you were saying about the audience and community relates to the context and raison d’être of the institution. And again, coming back to this question of language, the idea of the model is a modernist idea, but maybe it is quite useful in some aspects. For instance, modernists created architectural housing units that traveled around the world and became universal living spaces—which, of course, has its own problems. But it’s interesting to think about these models as traveling models that could actually infect the imagination, adapt and change in every context, be refused, destroyed, vandalized, etc. The hegemonic model is almost erased in such a process.

LK: The issue with the model is that it standardizes and removes context. But it’s the context that actually produces the model—the cultural and historical context, which is specific. Once it travels, the context disappears. There is a really great essay by Edward Said, “Traveling Theory Reconsidered,” where he writes about what happens when theory travels. When theory travels, especially theory that’s rooted in practice, or that’s produced by practice, its context disappears, and then it’s diluted. It’s no longer as radical as where it started from. Where it was necessary.

But Said wrote another text a few years later where he reconsiders this, positing the opposite: in its appropriation by another context, theory might actually bring back something revolutionary to the context of origin. I think this is extremely important. I mean, as you say Marwa, the problem with the model is that it standardizes. So it’s really important that no model becomes the first or only model, that there is no monoculture of models. There needs to be an understanding that a certain context produced this model and reproducing it is impossible. It will be reproduced differently in each context.

YK: When we speak about these models it’s important to speak about contexts. There is a connection between the locality of cultural practices and the globality of their effects. We need to be aware of these moves. You brought up modernity and the problem of working out a model without a context. This kind of practice doesn’t try to take itself away from the conditions that allowed it to happen. I keep saying that Sakakini happened by coincidence. It didn’t happen out of too much planning. There were material conditions and a material coincidence that allowed a group of people to take over this mainstream elitist institution and shift it. If it had been an open call for a job to bring in a new director, some of us would have been able to secure the job, but we could not have said, “Oh, we have this model that we want to share with you.”

MA: Maybe we could think more about the particularity of these institutions and experiences and experiments, while thinking about their universality or potential universality. Lara, in Edward Said’s second interpretation or reconsideration of the way theory travels, there is a kind of consideration of the resonance of what happens when something travels and comes back. The boomerang effect can produce something even more radical … and maybe this is an important aspect of the history of knowledge. I guess we’re speaking on two different levels: critiquing the modernist idea of the model, which is this kind of hegemonic and colonial universal form that doesn’t need any particularity. And at the same time refusing to stay solely in the particular locality. It would be interesting to think of how this contradiction has generated so many amazing so-called alternative models.

LK: Or experiences.

MA: Yes. Experiences, experiments …

YK: I think this is opening a big new …

MA: Chapter ?

YK: Chapter, which we can do in our third …

MA: Part.

YK: Third part.

MA: Part three.

YK: Part three of this discussion.

This conversation is part of the e-flux journal series “Speak to the Mic Please,” guest-edited by Marwa Arsanios. It was first aired on a radio program organized by the Scottish Sculpture Workshop in Lumsden. We would like to thank Sam Trotman and Jenny Salmean for their invitation to do the pre-recorded conversation.